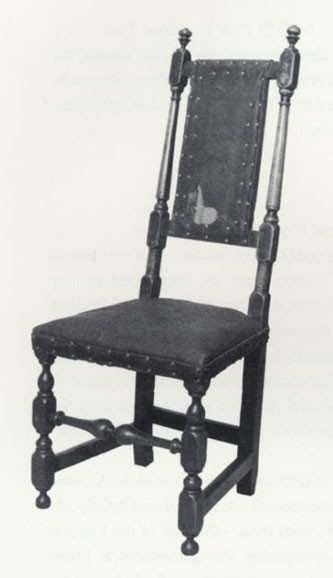

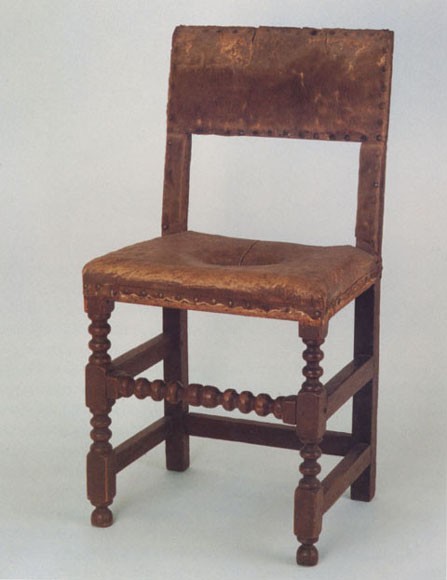

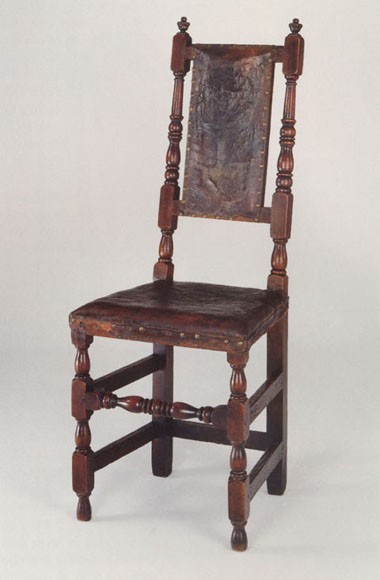

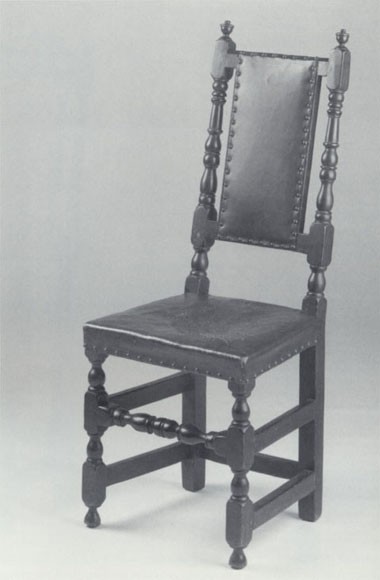

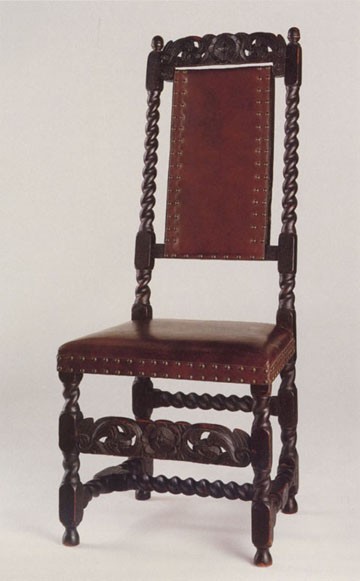

Side chair, Boston, ca. 1700. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 34 1/4", W. 17 3/4", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Wadsworth Atheneum.) In New York, Boston leather chairs of this type outnumbered carved examples approximately six to one.

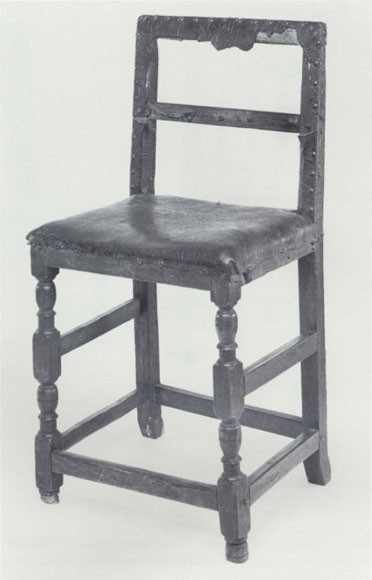

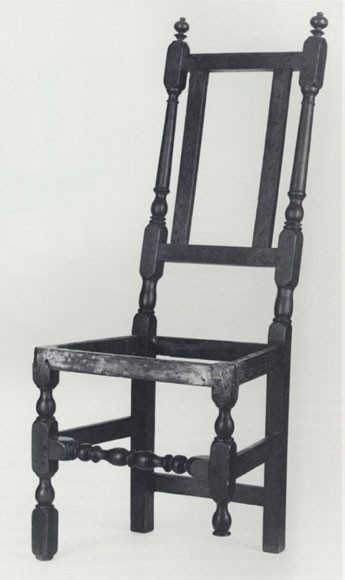

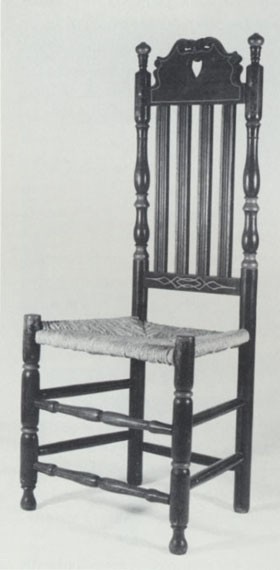

Side chair, Boston, 1650–1700. Birch and maple with ash. H. 35", W. 18", D. 15". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

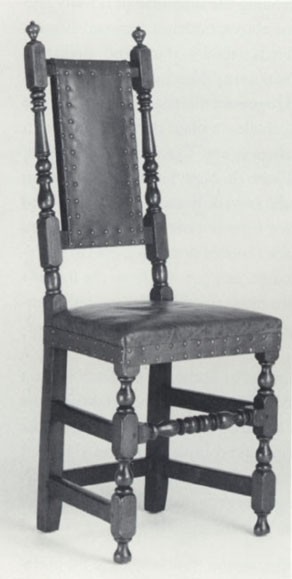

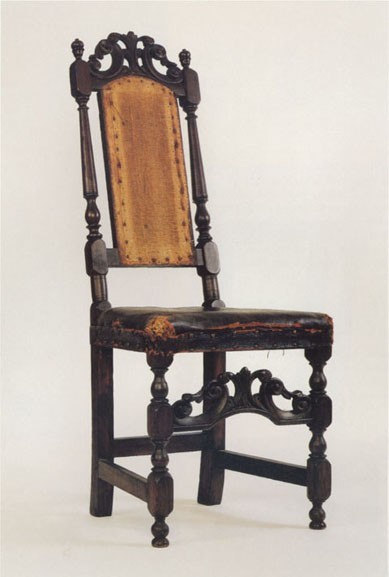

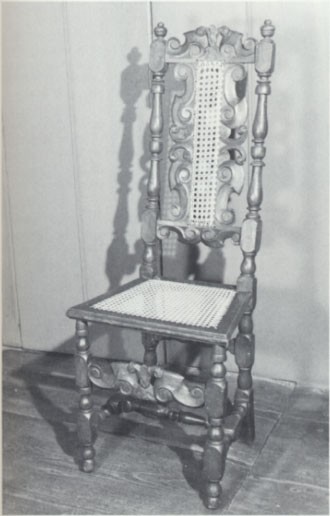

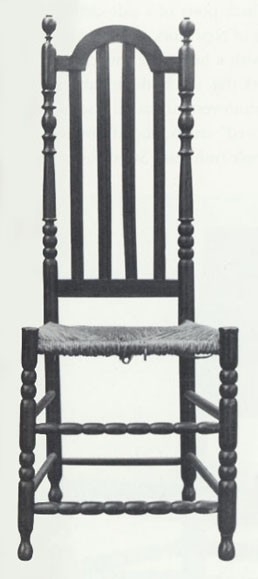

Side chair, New York City, 1705–1710. Maple and oak. H. 46 3/4", W. 18", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

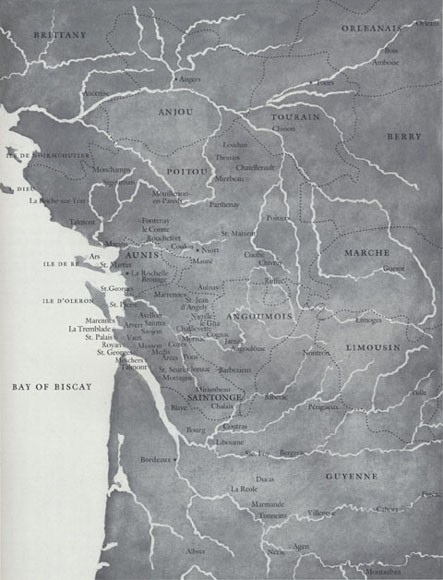

Map of Aunis-Saintonge, France.

Side chair, Boston, 1690–1705. Maple and oak. H. 41 3/4", W. 20", D. 18". (Courtesy, New York State Education Department, Albany.)

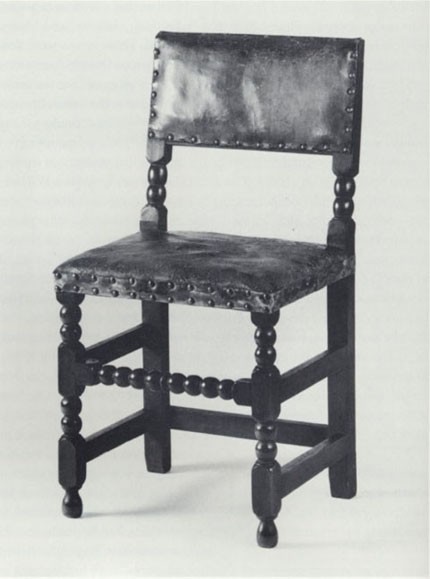

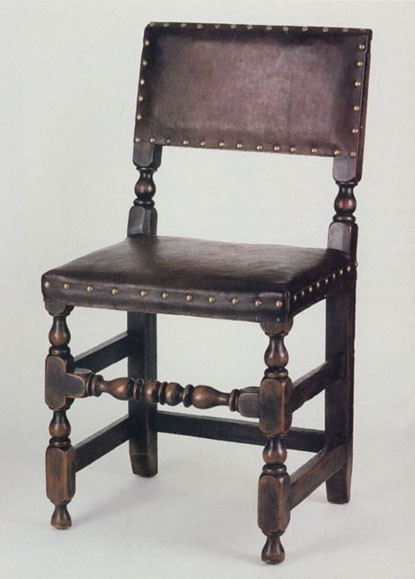

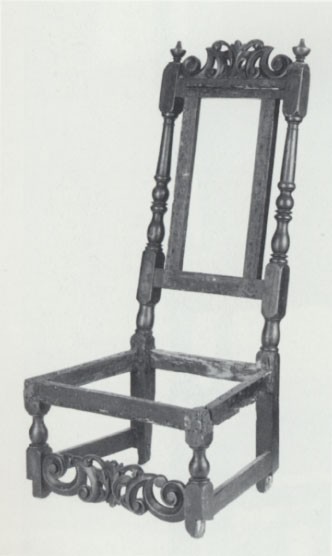

Side chair, New York City, 1660–1700. Maple and oak; original seal skin upholstery. H. 36 3/4", W. 18 3/4", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Saybrook Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The ball-and-cove and vase turnings on this chair differ from those on seventeenth-century Boston examples such as figs. 2 and 5. Seal skin was used when leather was unavailable.

Side chair, New York City, 1660–1700. Oak and black ash; original leather upholstery. H. 34", W. 18 1/4", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, John Hall Wheelock Collection, East Hampton Historical Society; photo, Joseph Adams.) This chair descended in the Wheelock family of East Hampton, Long Island.

Side chair, New York City, 1660–1685. Red oak. H. 37", W. 18", D. 15 1/8". (Courtesy, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Memorial Hall Museum, Deerfield, Massachusetts; photo, Helga Studio.) The inverted vase-and-barrel turnings on this and another related example at the Wadsworth Atheneum followed Amsterdam prototypes in an era when Netherlandish design was on the wane in New York City.

Side chair, New York City, 1685–1700. Maple and oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The turnings on this chair are closely related to those on late-seventeenth-century London cane chairs and early-eighteenth-century New York leather chairs, such as the one illustrated in fig. 3.

Grand Chair, New York City, 1680–1695. Maple stained red. H. 44 1/4", W. 22 1/2", D. 17 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Escritoire, New York City or northern Kings County, 1695–1720. Desk-on-frame, gumwood, possibly walnut veneer, tulip poplar. H. 35 1/4", W. 33 3/4", D. 24". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944, acc.44.47, All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) The turnings on the side stretchers are closely related to those on the front stretcher of the grand chair illustrated in fig. 10.

Detail of the finial of the grand chair illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Detail of a drawer pull on a kast, New York City or northern Kings County, ca. 1700–1740. Red gum, mahogany, white pine, tulip poplar, 82 1/2 x 75 3/8 x 28". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection L1994.3)

Side chair, New York City, 1705–1710. Maple and oak; original leather upholstery. H. 47 3/4", W. 18 1/2", D. 18 3/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

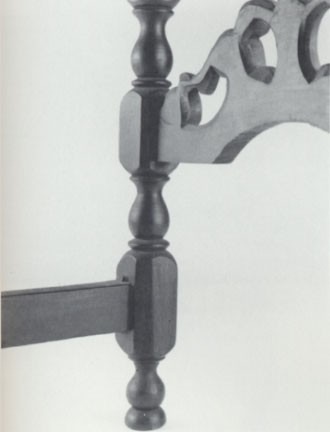

Detail of the finial of the side chair illustrated in fig. 14. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

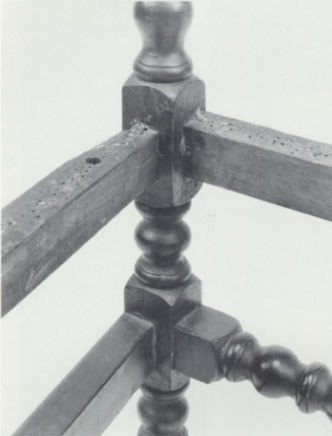

Detail of the understructure of the trapezoidal seat of the grand chair illustrated in fig. 10. (Photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Side chair, Boston or New York City, ca. 1700. Maple and oak. H. 47", W. 20", D. 21". (Private collection; photo, Christopher Zaleski.) This chair, branded “PVP” for Philip Verplank of Fishkill, New York, is related to three carved leather chairs at Washington’s Headquarters, Newburgh, New York. The latter are also branded “PVP.”

Detail of the understructure of the side chair illustrated in fig. 17. (Photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Side chair, New York City, 1700–1725. Maple with oak. H. 45 5/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection L1982.116; photo, Richard Eells.) This chair reportedly descended in the Pieter Vanderlyn family of Kingston, New York. Pieter immigrated to New York City from the Netherlands in 1718. His arrival date suggests he may have acquired the chair from an earlier owner.

Detail of the “French hollow” back of the side chair illustrated in fig. 19. The curvature is similar to that of the early carved leather chair illustrated in fig. 39

Cane chair, London, ca. 1700. Beech. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Neil D. Kamil.)

Side chair, New York City, ca. 1700. Maple. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The front stretcher is related to that of fig. 10. The feet and a portion of the right leg are missing.

Side chair, New York City, ca. 1700. Maple. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair is closely related to the one illustrated in fig. 22.

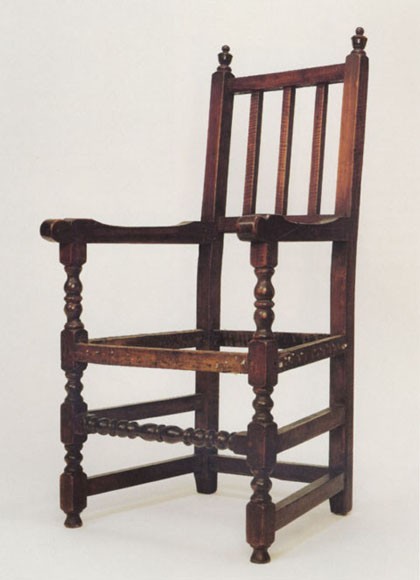

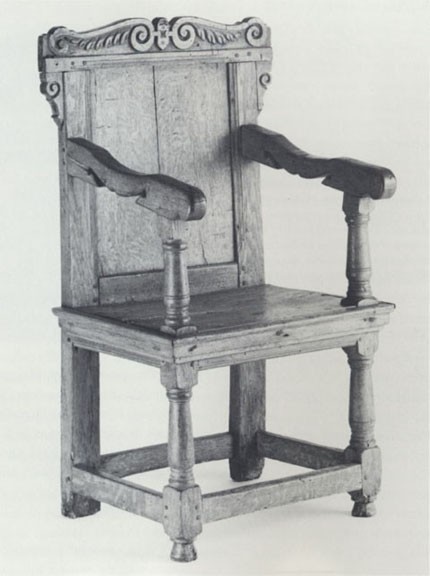

Joined great chair, New York, 1650–1700. Oak. H. 43", W. 23 3/4", D. 21". (Courtesy, Wallace Nutting Collection, Wadsworth Atheneum, gift of J. P. Morgan; photo, Joseph Szaszfai.) The left arm and seat are replaced, and the feet are missing.

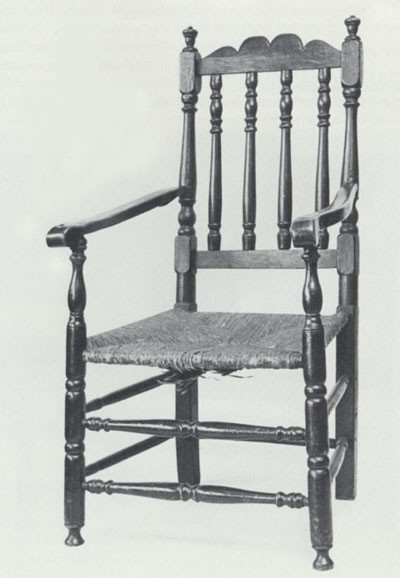

Armchair with carving attributed to Jean Le Chevalier, New York City, 1705–1710. Maple with oak and hickory. H. 47 1/2", W. 25 1/2", D. 27". (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The finials are incorrect nineteenth century restorations; the feet are more recent.

Leather great chair with carving attributed to Jean Le Chevalier, New York City, 1710–1730. Maple with oak. H. 53 3/4", W. 23 7/8", D. 16 3/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts., Boston. All rights reserved. Gift of Mrs. Charles L. Bybee; photo, Edward A. Bourdon, Houston, Texas.) This chair was damaged by fire while in the Bybee collection.

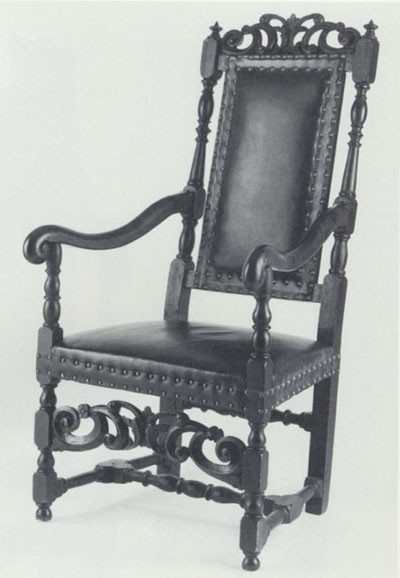

Armchair with carving attributed to Jean Le Chevalier, New York City, 1705–1710. Maple with oak. H. 52", W. 24 3/4", D. 17 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The low placement of the carved front stretcher is reminiscent of late seventeenth-century French fauteuils as well as some varieties of contemporary London cane chairs, which took French court furniture as a stylistic paradigm under the influence of refugee Huguenot artisans, especially after 1685. The left scroll volute of the crest is a replacement.

Side chair with carving attributed to Jean Le Chevalier, New York City, 1705–1710. Maple with oak. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Composite detail showing (from top to bottom) the crest rails of the chairs illustrated in figs. 26, 27, and 28 and the stretcher of the chair illustrated in fig. 25.

Armchair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, 1700–1710. Maple with oak; original leather upholstery. H. 47 1/2", W. 23 3/4, D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. Arthur Tracy Cabot Fund, 1971.624.) Acanthus-carved arms such as these were common on late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century French upholstered seating furniture.

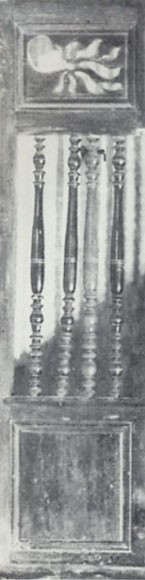

Baptismal screen in the church of St. Étienne, Ars-en-Ré, Île de Ré, France, 1625–1627. Oak. (From Inventaire Général des monuments et des Richesses Artistiques de la France, Commission Régionale de Poitou-Charentes, Charente-Maritime, Cantons Île de Ré; photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Detail of the baptismal screen in the church of St. Étienne, Ars-en-Ré, Île de Ré, France, 1625–1627. Oak. (From Inventaire Général des monuments et des Richesses Artistiques de la France, Commission Régionale de Poitou-Charentes, Charente-Maritime, Cantons Île de Ré; photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Black chair, Long Island Sound region, perhaps southeastern Westchester County, 1705–1730. Maple and ash. Dimensions not recorded. (Dey Mansion, Wayne Township, New Jersey; photo, Neil D. Kamil.)

Black great chair, probably Tarrytown, Westchester County, 1705–1730. Woods unidenti€ed. H. 44 1/2", W. 25", D. 26 1/4". (Courtesy, Historic Hudson Valley.)

Couch, New York City or coastal Rhode Island, 1700–1715. Maple. H. 42 1/8", W. 74 3/8", D. 25 1/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair attributed to Pierre or Andrew Durand, Milford, Connecticut, 1710–1740. Maple and ash. H. 45 1/4", W. 19 1/2", D. 14 3/4". (Anonymous collection; photo, New Haven Colony Historical Society.)

Side chair, probably London, 1685–1700. Woods and dimensions not recorded. (Photo, Symonds Collection, Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Museum.)

Side chair, London, 1690–1700. Beech with turkeywork cover. H. 48 3/4", W. 21 7/8", D. 17 5/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. ©2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved; Gift of Mrs. Winthrop Sargent, in memory of her husband 17.1629.)

Side chair, New York City, 1685–1700. Maple. H. 48", W. 20 1/4", D. 22". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of crest rail, posts, and finial of the side chair illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details of three carved panels on the choir screen in the church of St. Étienne, Ars-en-Ré, Île de Ré, components ca. 1629: (a) Christ gathering his flock; (b) acanthus-leaf foliage; (c) winged cherubs holding an urn. Oak and walnut. (From Inventaire Général des monuments et des Richesses Artistiques de la France, Commission Régionale de Poiton-Charentes, Charente-Maritime, Cantons Île de Ré; photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Detail of one of the earliest panels in the choir screen in the church of St. Étienne, Ars-en-Ré, Île de Ré, ca. 1580. (Photo, Christopher Zaleski.)

Joined great chair, probably New York City, ca. 1675. Oak. H. 42 1/2", W. 25", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Jean Le Chevalier’s grandfather, “Jan Cavelier,” was one of the most important carvers in New York during the era when this chair was made.

Detail of the carved crest rail of the great chair illustrated in fig. 43. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The compressed, diamond-shaped aperture surmounted by a lunette at the nexus of the opposing scrolls is repeated in the carving of the sunflower on the crest rail of the New York leather chair illustrated in figs. 39, 40.

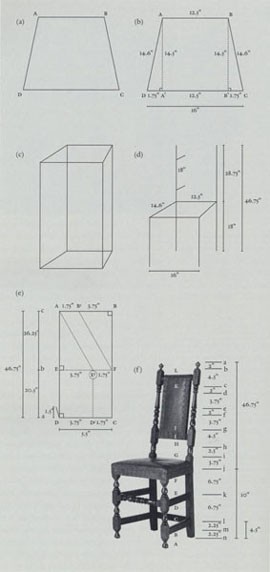

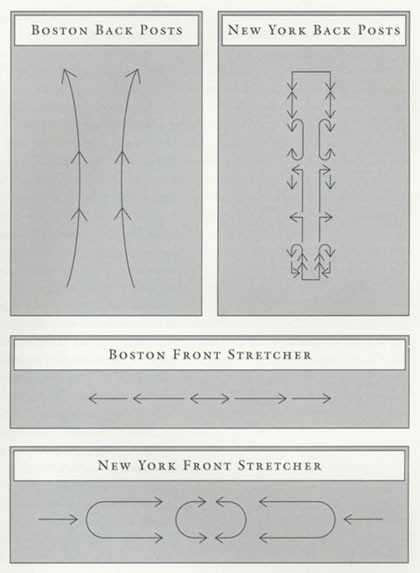

Flow diagram representing the formal opposition of turning patterns on Boston and New York plain leather chairs, exempli€ed by figs. 1 and 3, respectively. (Drawing, Neil D. Kamil; art work, Wynne Patterson.)