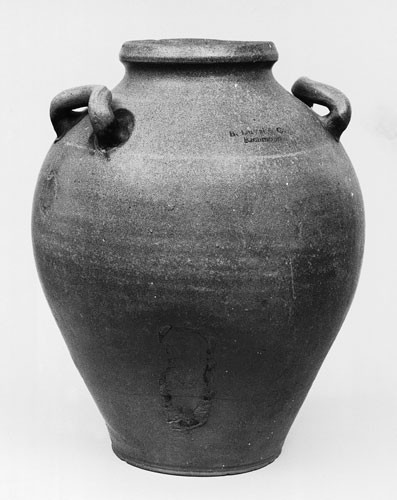

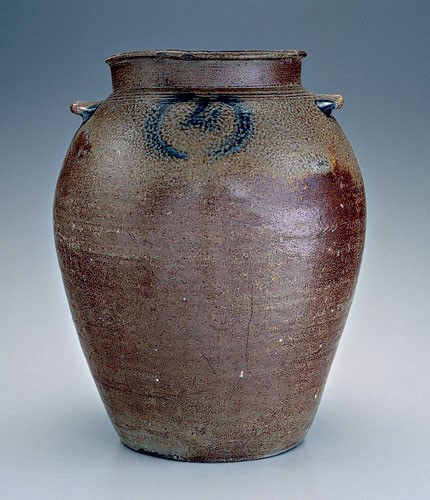

Storage jar, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This three-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “B. DuVal & Co./ Richmond.”

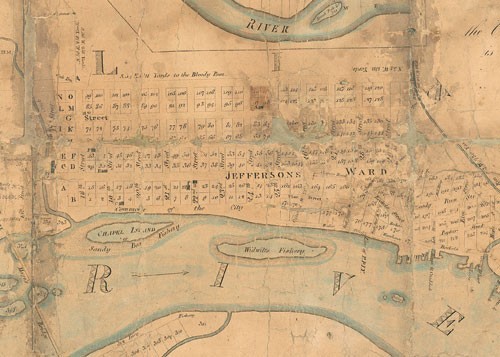

A Plan of the City of Richmond, Richard Young, 1809–1810. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.)

Detail of the Richard Young map showing lots 39, 40, 53, and 54. The approximate location of the DuVal kiln, based on recent research, is shown.

Fragments of DuVal stoneware that littered the construction site. (Photo, David Hazzard.)

Construction machinery on the site of the Benjamin DuVal Pottery. (Photo, David Hazzard.) Archaeologists had to retrieve artifacts while this machinery was in motion. The empty hole in front of the excavator is where the kiln foundation and a massive waster pit were uncovered.

Brickwork from the foundation of the DuVal kiln. (Photo, David Hazzard.) The majority of the rectangular kiln foundation appeared to be intact when first uncovered. Unfortunately, it was removed by grading machinery one afternoon, before any archaeological recording could begin. Other portions of the kiln were later found at the construction debris landfill.

Volunteers collecting sherds from a recently excavated part of the site. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Boxes of collected stoneware fragments and kiln furniture. (Photo, David Hazzard.) Far from an ideal archaeological recovery, this rescue eVort nevertheless resulted in the salvage of approximately forty boxes of artifacts.

John Kille and Marshall Goodman arriving at one of the construction landfills to see where the debris from the Benjamin DuVal Pottery site was being dumped. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

David Hazzard, Marshall Goodman, and John Kille examine one of the hundreds of fragments recovered from the dump site. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Archaeologist David Hazzard investigates a pile of clay roofing tiles. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments are undoubtedly associated with DuVal’s Richmond Tile Manufactory, which opened in 1807. No other information was recovered that shed additional light about that operation.

Jar or jug base fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (All artifacts courtesy Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment displays the characteristic wire marks that result when a wet vessel is cut from the wheel.

Jar and jug base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These bases show different methods of cutting wet pots from the wheel. The techniques may have varied among the individual potters.

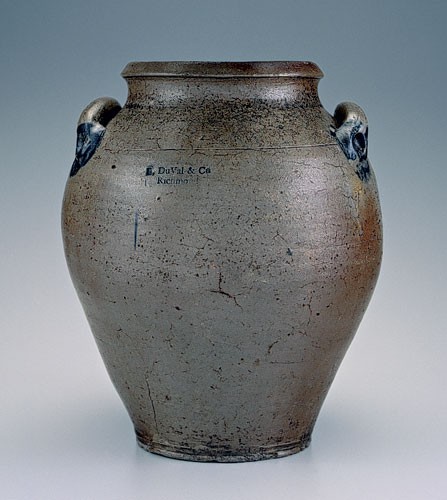

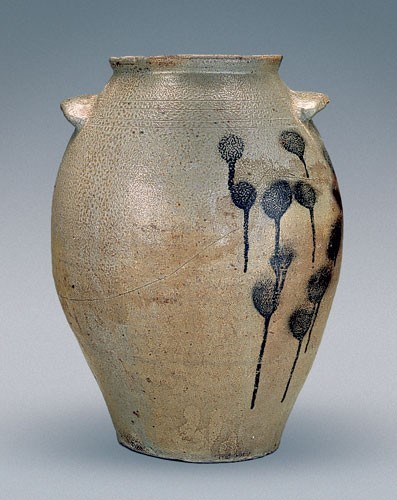

Storage jar, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This three-gallon ovoid jar displays the impressed mark “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond.”

Detail of the maker’s mark on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14.

Detail of the handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14.

Jar strap-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These were probably from two-gallon jars.

Jar strap-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This handle was part of a very large jar, possibly five gallons in size.

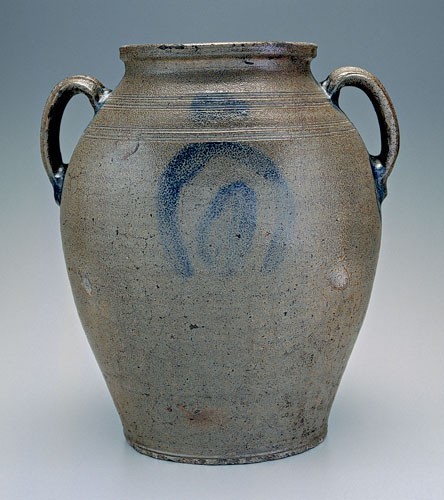

Storage jar, attributed to Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the vertically placed strap handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 19.

Jar lug-handle fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the handle on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 22.

Storage jar, attributed to Loudoun County, Virginia, ca. 1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the handle on the jar illustrated in fig. 24.

Jar rim fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These wide-mouthed, cylindrical jars are similar in shape to the one-gallon jar illustrated on the left in fig. 27 (note the brown iron oxide wash on that example).

Storage jars, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 12". (Private collection.) Right: H. 12". (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society; photo, Ron Jennings.)

Jar fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) These small jar fragments probably represent the 1/8-gallon (one pint) jars advertised by DuVal, which undoubtedly he used in his apothecary business.

Jug neck and mouth fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Dozens of these jug fragments were collected. The vast majority have similar reeding of the neck and placement of the handle terminals.

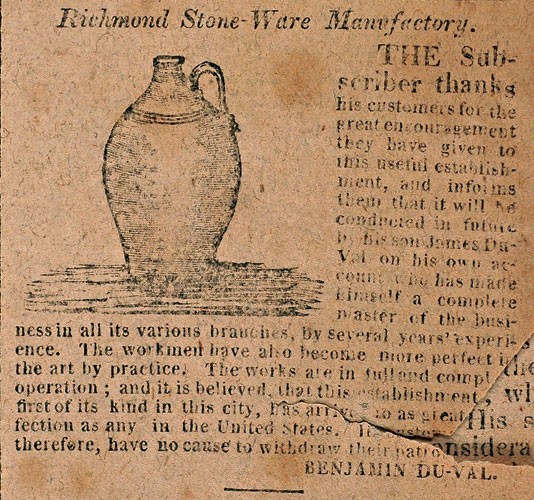

Detail of a newspaper advertisement for the “Richmond Stone-Ware Manufactory,” published in the Richmond Enquirer, May 9, 1817. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.)

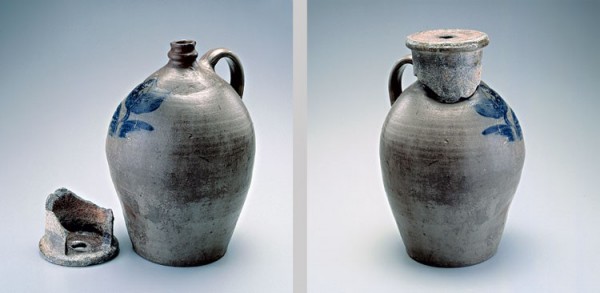

Jug, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the straight attachment of the handle to the shoulder in the detail above.

Jug, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the straight attachment of the handle to the shoulder in the detail above.

Jug fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments represent typical jug necks.

Jug fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This large fragment belongs to a four- or five-gallon jug. Note the handle attachment on the shoulder of the pot, well below the neck.

Jug or jar base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These base fragments provide evidence of the graduated vessel sizes produced at the pottery. The range of colors on these fragments illustrate the variations possible in the firing process.

Pitcher fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Fragments of pitcher collars showing the profile of the pinched spouts. The small pitcher fragment on the right shows the upper handle attachment.

Bottle neck fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These fragments are typical bottle neck profiles recovered from the pottery site.

Bottle neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This bottle neck shows the unusual addition of cobalt highlights.

Bottle fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This bottle fragment with the impressed “R. Adams.” may have been custom-produced for Richard Adams, one of Richmond’s wealthiest citizens and a leading real estate developer. Adams’s home was located just a few blocks north of the DuVal kiln site.

Flasks or tickler fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) DuVal’s advertisements list small pocket or “tickler” flasks. Fragments of numerous oval-shaped flasks were recovered at the pottery site. The body fragment on the left is unusual, as it has been flattened on both sides, possibly to fit into a wooden case.

Chamber pot fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These handled chamber pots are similar in shape to others that were being produced in Alexandria and Baltimore in the early nineteenth century. Note the dimple beneath the lower handle attachment on the body fragment on the right.

Jar or churn neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Unusual throwing rings remain on the exterior of this large jar neck. A shelf or flange inside the lip suggests that a lid was associated with this vessel, possibly making it one of the churns listed in DuVal’s advertisements.

Milk pan or shallow bowl fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This unusual bowl-like fragment may represent one of the milk pan forms listed in DuVal’s advertisements.

Jug stackers, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jug stackers were one of most common forms found during the salvage recovery. Note the graduation of sizes to accommodate the wide variety of jug capacities produced at DuVal’s pottery. The cutouts are for jug handles.

Jug and stacker collar, John P. Schermerhorn, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although it was not produced at the DuVal pottery, this Richmond-made jug illustrates the placement of the stacker collar over the mouth and neck of the jug. The stacker is designed to provide a level surface on which to place another jug. The hole in the stacker allows the gases to escape from the jug’s interior. Note the indentations on the jug’s shoulder where the stacker made contact.

Jug neck fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These large jug necks show the differential coloration resulting from uneven distribution of the airborne salt gases due to the placement of the stacking collars. The jug on the left collapsed from the weight and extreme heat during firing.

Kiln furniture, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) A variety of kiln furniture was employed in the stacking and firing of DuVal’s kiln. The specially prepared circular and angular pads on the right served to separate vessels, whereas the clay strips and globs offered an expedient way to level pots and seal gaps in the kiln.

Fused jar fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These jar fragments, which partially melted during a firing, provide direct evidence of the stacking methods used in the kiln. Note the fire-clay spacers used between the jar mouths. Jars were stacked base to base and mouth to mouth.

Jar base fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Note the fused spacers adhering to the bottoms of these over-fired jar bases.

Jar and jug fragments with impressed marks, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Out of the thousands of fragments collected during the DuVal salvage recovery, fewer than a dozen had impressed marks. The historical documentation suggests that the “B. DuVal & Co/Richmond” mark was used from 1811 until 1817, when Benjamin DuVal’s son James took over the operation of the pottery.

Jar or jug fragments with impressed marks, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1818. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) These marks may have been used by James DuVal when he took over his father’s stoneware manufactory in 1817. The full impressed mark might have read “duval stoneware manufactory/ richmond va.,” but no intact vessel with this mark has been found.

Jar or jug fragments, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These incised fragments were the most enigmatic artifacts found during the DuVal salvage recovery. They suggest very high quality incised decoration previously unassociated with the DuVal operation or, for that matter, any Richmond-area stoneware.

Jar fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment, which is from a large four- or five-gallon jar, has a wavy incised line on what would have been the shoulder.

Incised body fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) While seemingly rudimentary, this incised sherd may be part of a larger design.

Jug neck fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) This simple incised leaf filled with cobalt must have been produced in some quantity, though no extant examples have been identified.

Jar fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This fragment is from the shoulder of a large, probably five-gallon, storage jar. The five cobalt "fingerprints" might signify the jar's capacity.

Pitcher handle fragment, Benjamin Duval Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware, (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This delicate strap handle probably belonged to a quart-sized pitcher. Note the "fingerprint" decoration on the handle.

Jar Fragment, Benjamin DuVal Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1811-1820. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)