Gustavus Hesselius, portrait of Stephen West, Sr. (1690–1752). Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) West acquired Rumney’s Tavern in 1724. The portrait is superimposed on a detail of a delftware mermaid plate used at Rumney’s Tavern.

Gustavus Hesselius, portrait of Stephen West, Sr. (1690–1752). Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) West acquired Rumney’s Tavern in 1724. The portrait is superimposed on a detail of a delftware mermaid plate used at Rumney’s Tavern.

John Greenwood, Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, 1758. Oil on canvas. 37 3/4" x 75 1/4". (Courtesy, Saint Louis Art Museum.) Eighteenth-century prints and paintings have recorded numerous depictions of tavern life. These leave little doubt as to the large amounts of ceramics and glass that would succumb during a night of spirited revelry.

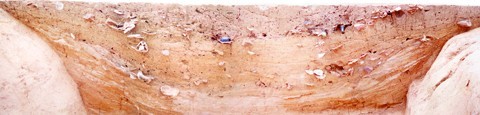

The Rumney/West cellar pit during the course of excavation with the contents of the eastern half removed. The once straight sides of the cellar were eroded away during its useful life. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

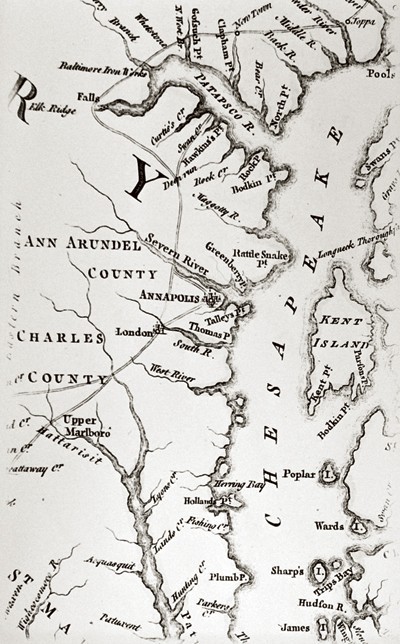

Detail of Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson’s Map of the Most Inhabited part of Virginia, containing the whole province of Maryland with Part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. 1754. (Courtesy, London Town Foundation.) This detail shows the important relationship of London Town, Maryland, to the colonial road system.

A circa 1840 painting of London Town from across South River. (Courtesy, Edmondo Collection.) This view, looking south from the ferry master’s house, shows a number of structures still surviving long past the town’s heyday.

Reconstructed view of London, Maryland. Lee Boynton, 1997. (Courtesy, London Town Foundation.) This painting was based on preliminary archaeological findings along Scott Street and the South River. A view of the William Brown House and Tavern across what was once busy Scott Street; today, an overgrown gully.

Drawing of the building footprints reconstructed from posthole patterns excavated along Scott Street. The area that has been archaeologically exposed so far is impressive for its dense, thoroughly urban layout.

The painstakingly careful excavations of the cellar, carried out over nearly five years, sometimes resembled an operating theater. Here, Lost Towns staff members can be seen working on a pig’s jaw and one of three delftware plates bearing a pagoda motif. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

This view of the southwest quarter during excavation shows the popularity of oyster shells as tavern fare. Ceramic and wine bottle fragments, bricks, pig bones, and a barrel hoop complete the assemblage. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Examples of glassware recovered from the Rumney/West cellar. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A scent bottle and medicinal vials are in the foreground of this grouping. The wine bottles represent the stylistic extremes recovered from the deposit, ranging in date from approximately 1700 to 1725. The trumpet shaped wineglass was a unique find; fragments with knopped stems were more common. One faceted wine glass had the inscription “God Save King George” and is believed to date from the coronation of George I in 1714.

Saucer and tea bowl fragments, China, ca. 1725. Porcelain. D. of saucer: 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This export porcelain saucer, along with small fragments representing a number of porcelain cups, are clear indications of the fashionable consumption of tea at the Rumney/West Tavern.

Chamber pot, Germany, ca. 1725. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This utilitarian object was found in close association with a “mermaid” plate.

Mug, England, probably London, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This nearly complete example is one of a number of English brown stoneware mugs recovered. At least two bore the impressed “WR” excise stamp.

Mug, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Several Staffordshire white salt-glazed stoneware mugs were recovered. All had slip-dipped iron-oxide rims.

Pitcher fragment, England, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bowl, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This stoneware bowl and similarly sized delftware bowls may have been used as coffee cups.

Tea bowl and saucer, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tea bowl: 1 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These two objects were found lying side by side in the excavation.

View of a single excavation level in the southwest quarter of the cellar. This image shows the white salt-glazed stoneware tea bowl and saucer lying amongst the remains of an English stoneware mug, wine bottle fragments, and oyster shells. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Coffee pot fragments, England, ca. 1720. Lead-glazed stoneware. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These English brown and off-white stoneware coffee pot fragments, including part of the handle and the acorn shaped finial from the lid, are taken as an indication of high status clientele in this circa 1725 context.

Mug, England, ca. 1720. Stoneware. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Garry Atkins; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An antique specimen of the lead-glazed stoneware represented by the coffee pot fragments illustrated in fig. 19.

Profile of plate, London, ca. 1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This low profile, lacking a foot ring, is typical of London manufacture. It was present on sixteen of seventeen excavated delftware plates.

Plates, London, ca. 1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two of the four “sunower” plates recovered from the lowest levels of the cellar fill.

Plates, London, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These English versions of a Chinese pagoda motif appeared on three excavated examples.

A tin-glazed earthenware mermaid plate is shown here in situ during the first weeks of excavation. It was found intermingled with fragments of a Rhenish chamber pot (and the remains of meals), in the cellar’s northeast quadrant. (Photo, Al Luckenbach.)

Plate, London, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) One of three plates recovered that were decorated with the image of a mermaid. This motif now serves as the logo for the Historic London Town Park in Edgewater, Maryland.

Tea bowls, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These delft tea bowls vary slightly in size, a tribute to the lack of standardization during this early period. Although quite delicate and thin by tin-glazed earthenware standards, they are still thicker than what could be achieved with the newer, white salt-glazed stoneware.

Bowls, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. of tallest: 4 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Numerous delftware bowls attest to the popularity of punch at the Rumney/West establishmen

Spiked bowl, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. to top of spike: 1 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This so-called “pineapple bowl” may have held butter or sugar instead. Note the interesting use-wear patterns that appear on all three edges of the pyramidal projection.

Chamber pot, England, ca. 1725. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.

Jar, North Devon, England, ca. 1720. Gravel-tempered earthenware. H. 10 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although gravel-tempered earthenwares from the North Devon area are very frequently encountered at seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century archaeological sites in Anne Arundel County, this example from Rumney’s cellar is the most complete vessel yet recovered.

Jar, possibly Maryland, ca. 1725. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 3/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This tall, redware jar is a candidate for being a local product. Documentary evidence indicates that a potter named John Wamsley was active on the opposite shore of the South River during this time period.

Basin, Staffordshire, ca. 1720. Manganese-mottled earthenware. H. 4 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pipkin, Holland, ca. 1700. Yellow-glazed earthenware. H. 2 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two buff-bodied yellow-glazed earthenware vessels were recovered with profiles matching Dutch forms.

School children help screen plow zone soils for artifacts. (Photo, Al Luckenbach).

Profile of the cellar fill at the halfway point of excavation. A life-sized version of this illustration has now been mounted in Rumney’s cellar as a permanent exhibit. (Illustration, Severn Graphics.)