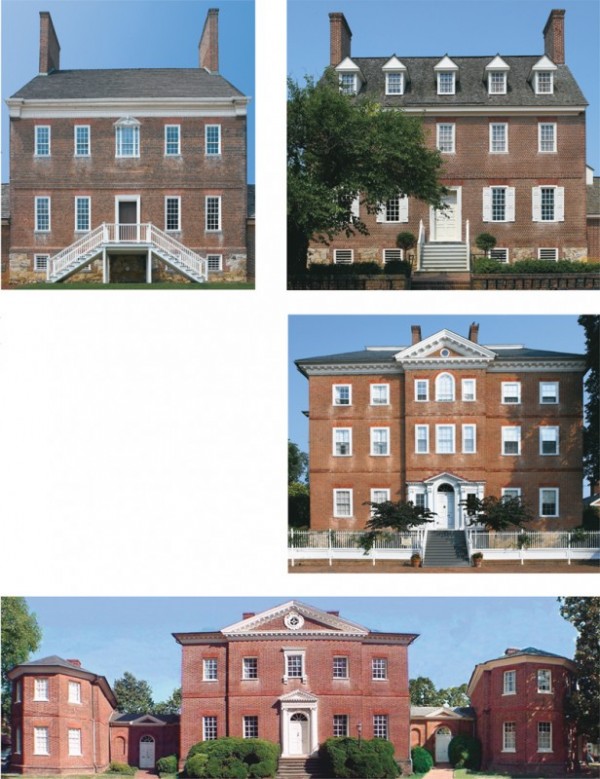

Composite illustration showing, clockwise from top left, four of the most significant houses built during Annapolis’s age of affluence: (a) James Brice House (1767–1773), (b) William Paca House (1763–1775), (c) Chase-Lloyd House (1769–1774), (d) Hammond-Harwood House (ca. 1774). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 3/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Several chairs similar to this example have been documented or attributed to Shaw’s shop.

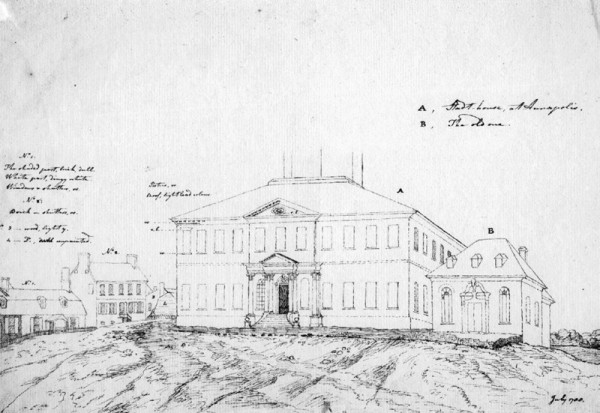

Charles Willson Peale, Front Elevation of the Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1788. Pen and ink on paper. 7 3/4" x 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, William Voss Elder Collection.)

Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1772–1779. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This photograph shows the original entrance of the State House. The portico was replaced in 1882, but this was the primary entry for the capitol until the completion of the 1902–1905 annex on the opposite side of the building.

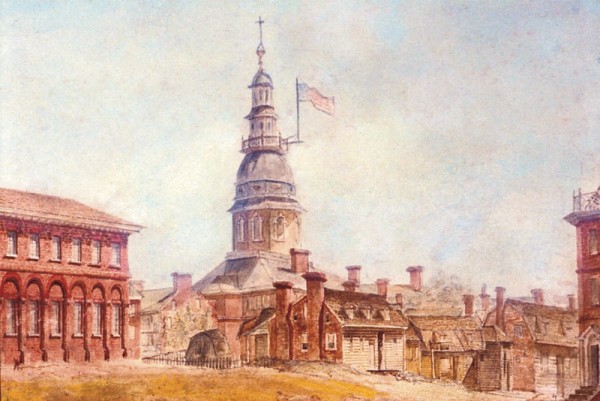

Detail of Charles Cotton Millbourne, View of Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1794. Watercolor on paper. 10" x 16 5/8". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association.) The State House, depicted in the center, dominated a landscape that changed very little in the decades that followed the Revolution. Cabinetmaker John Shaw procured the flag shown on the dome for the 1783–1784 meeting of the Continental Congress in Annapolis.

Charles Willson Peale, A Front View of the State-House &c. at ANNAPOLIS the Capital of MARYLAND, ca. 1789. Engraving on paper. 4 3/4" x 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, Bond Collection.) This image, which appeared in the Columbian Magazine in February 1789, shows the State House soon after the completion of the dome. Other buildings visible on State House Circle include the home of John Shaw (far left), the council chamber and ballroom (built ca. 1718) (right), the octagonal outdoor privy known as the “public temple,” and the treasury building (built 1735–1736).

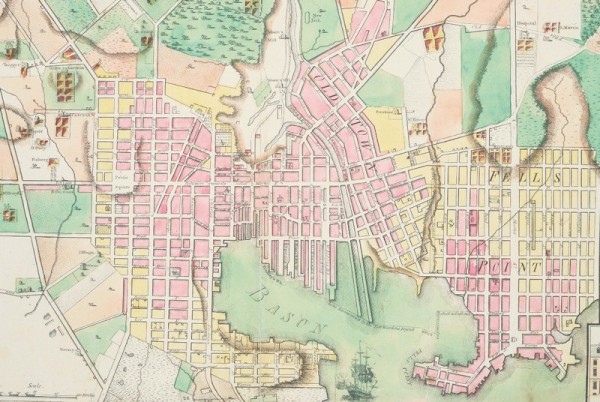

Detail of Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore, 1801. Watercolor on paper. 28 1/2" x 20". (Courtesy, George Peabody Library Collection, Johns Hopkins University.) This image shows the extent and potential for Baltimore’s growth at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

John Shaw House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1720–1725. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress.) By the time this photograph was taken (before 1890), Shaw’s house had been enlarged several times. The widow’s walk may have been installed before 1820, and the front porch was probably extended in the beginning of the twentieth century.

Cellaret probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1795. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 28 1/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 14 3/4". (William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 101.)

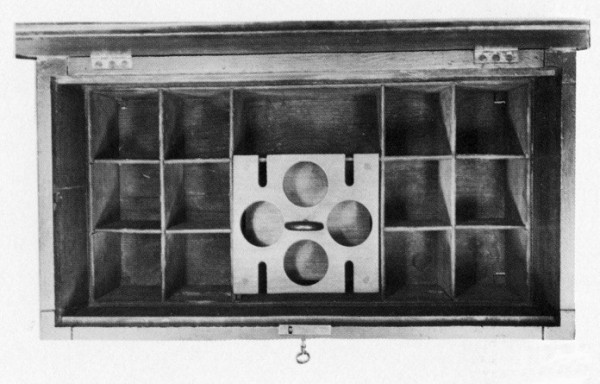

Detail showing the interior of the cellaret illustrated in fig. 9. (William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 102.)

Cellaret attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1795. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 28 1/4", W. 29 3/4", D. 14 3/4". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This cellaret is nearly identical to the one illustrated in fig. 9.

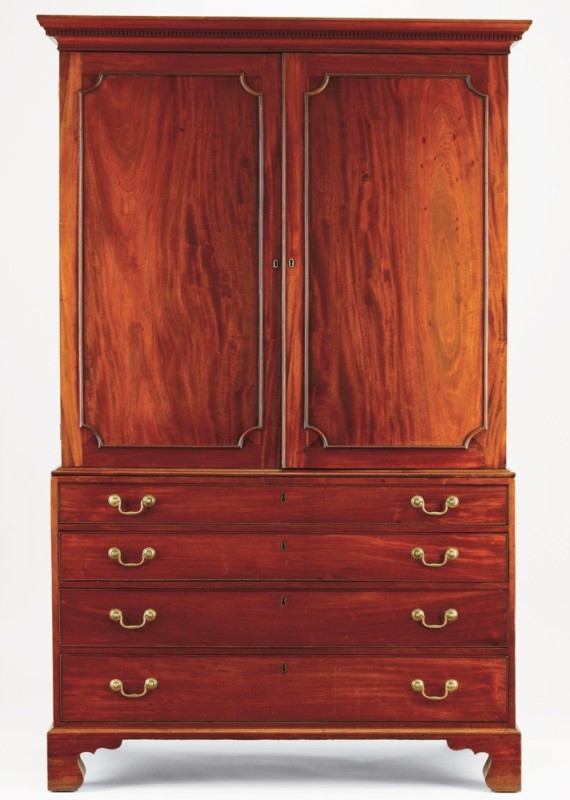

Clothespress probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1795. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 81 1/2", W. 49 7/8", D. 25". (Courtesy, Maryland Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

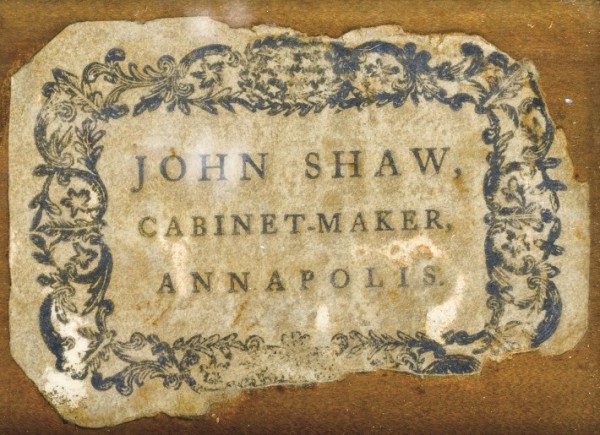

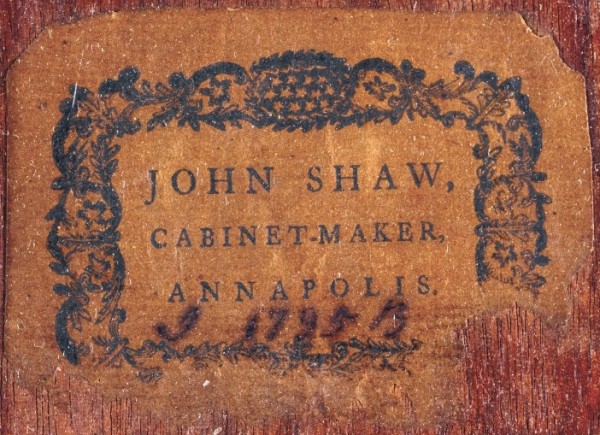

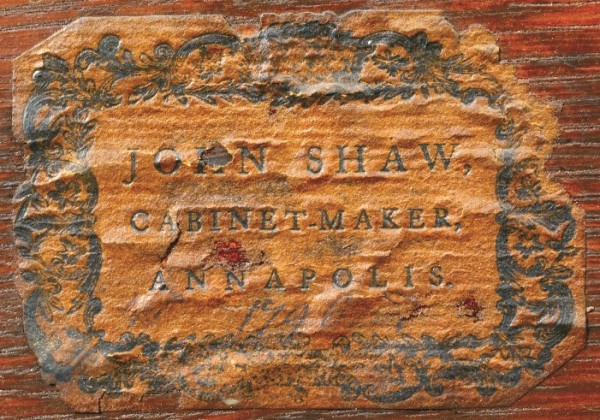

Detail of the label on the clothespress illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Clothespress probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JB,” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1795. Mahogany and mahogany veneer with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 80 1/4", W. 51 3/8", D. 24 3/4". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The initials on the label may be those of John Walter Battee, “aged eighteen years the 18th day of November 1793,” who apprenticed to John Shaw on November 5, 1793, to “learn the . . . business of Cabinet Maker & Joiner to serve until he be of Age of which will happen on the eighteenth Day of November 1796” (Anne Arundel County Register of Wills, Orphans Court Proceedings, liber JG1, February 14, 1794, fols. 415–16, MSA C 125-4). The initials and date on the label correspond with Battee’s tenure with Shaw, and he may also be responsible for the “J 1796 B” on the label on the bureau with secretary drawer illustrated in fig. 25. It is not known whether Battee continued making furniture after concluding his apprenticeship in November 1796.

Detail of the label on the clothespress illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Clothespress probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JH” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine. H. 92", W. 51 1/2", D. 25". (Courtesy, Baltimore Museum of Art, Friends of the American Wing Fund, BMA 1976.76.)

Detail of one of the laminated glue blocks supporting the case and feet of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 18.

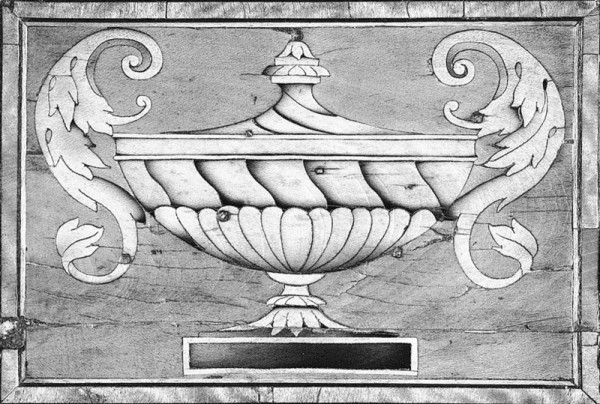

Detail of the urn inlay on the center tablet of the pediment of the clothespress illustrated in fig. 18.

Card table probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1796. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white oak. H. 28 3/4", W. 36", D. 17 3/4" (closed). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlay on the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the fly rail hinge and alignment mortise and tenon on the leaves of the card table illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Bureau with secretary drawer probably made by a journeyman whose initials were “JB” in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1796. Mahogany, mahogany veneer and lightwood inlay. H. 43", W. 44 3/4", D. 21 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This bureau has vertical back boards that are set in rabbets in the sides and top and secured with nails. The dustboards occupy the full depth of their dadoes and extend all the way to the back of the case. The case and feet are supported by square vertical glue blocks that butt against triangular blocks that fill the space between the bottom of the case and bottom edge of the front and side moldings.

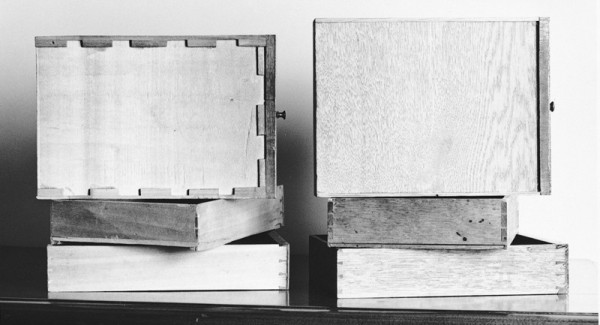

Detail showing the construction of the small drawers in the writing compartment of the bureau illustrated in fig. 25. Different techniques were used in the construction of the drawers indicating that at least two different artisans collaborated in the production of this piece.

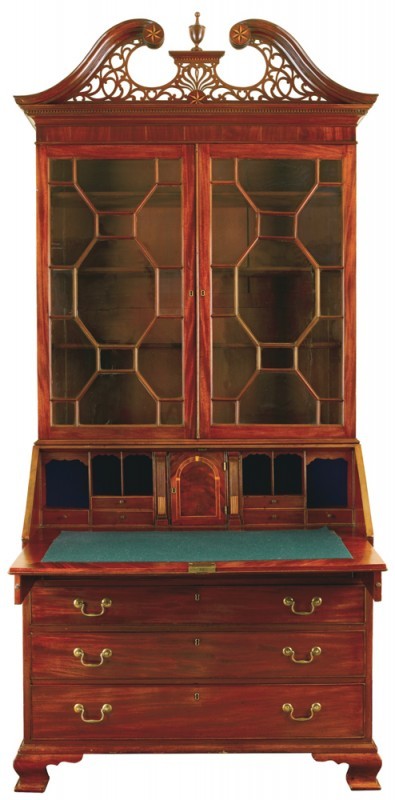

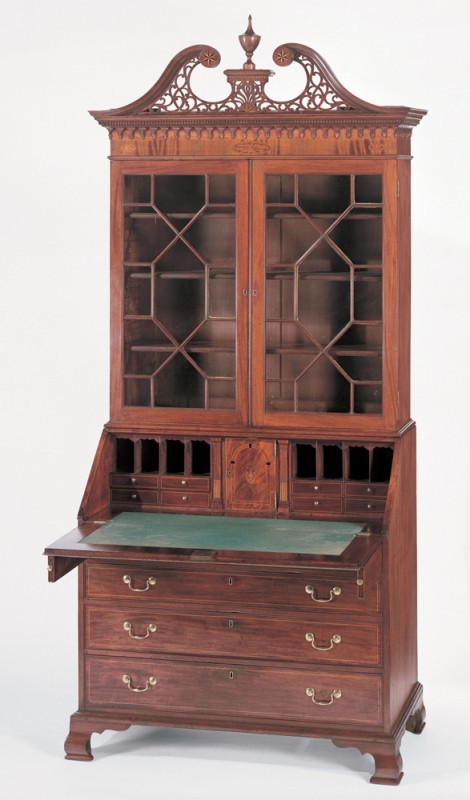

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 98 1/4", W. 47 3/8", D. 23 1/2". (Courtesy, Hammond-Harwood House Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk-and-bookcase attributed to the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1790–1800. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 98", W. 46", D. 24". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

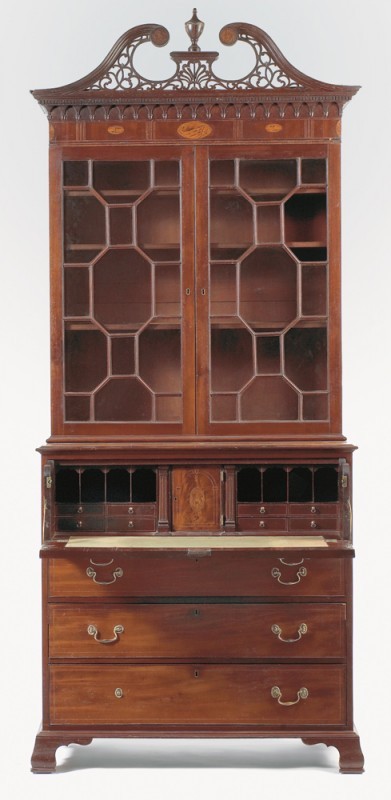

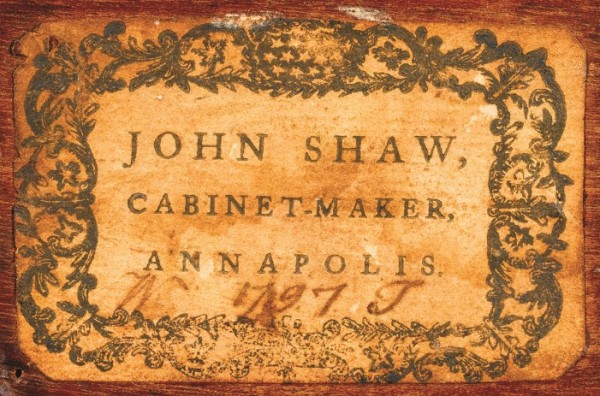

Desk-and-bookcase probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar, yellow pine, and white oak. H. 98 5/8", W. 45 3/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, White House Historical Association (White House Collection); photo, Bruce White.) The Shaw label on this desk-and-bookcase is inscribed “W 1797 T,” as are the labels on the card table and clothespress illustrated in figs. 12 and 21.

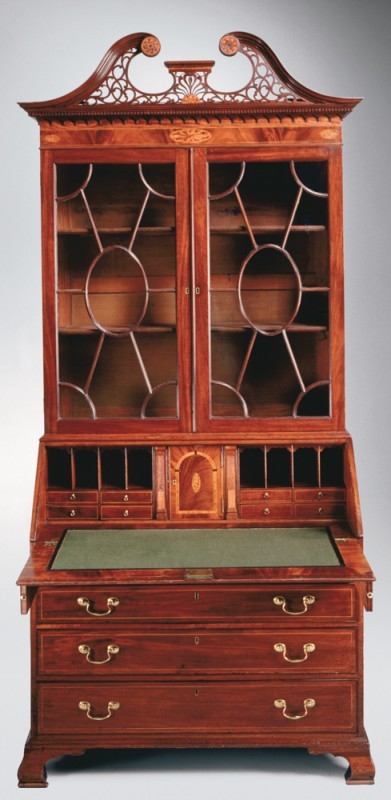

Secretary-and-bookcase probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine and tulip poplar. H. 105", W. 45 1/2", D. 21 5/8". (Courtesy, Christie’s; photo, Ellen McDermont.) The secretary-and-bookcase has an upper case with a four-panel back, a lower case with horizontal backboards that are nailed into rabbets in the top and sides, feet with square, laminated glue blocks, and a red wash or pinking on many of the secondary surfaces.

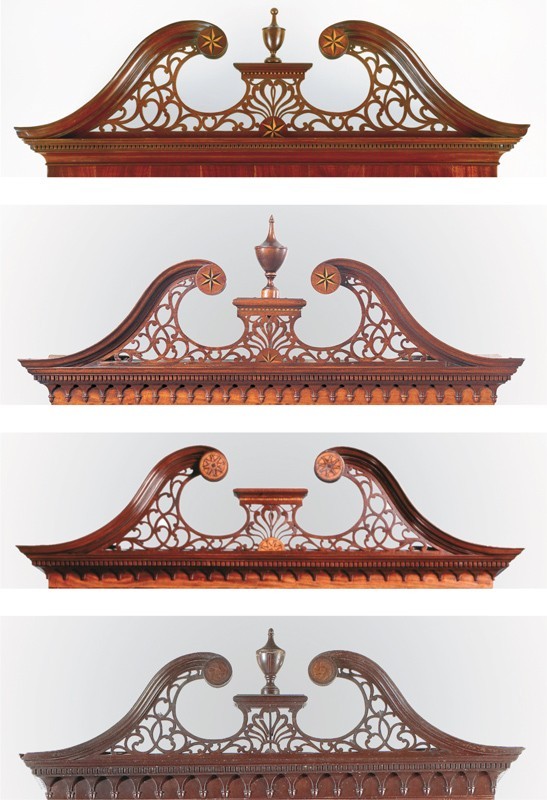

Composite detail showing the pediments of the desk-and-bookcases and secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in (from top to bottom) figs. 27–30. Shaw purchased most of his inlays from Baltimore specialists, including the eagles on the card table illustrated in figs. 21 and 23 and prospect door of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in figs. 30 and 33, and much of the other work illustrated in this article. A few inlays, like the urn on the pediment of the press illustrated in figs. 18 and 20, may represent British imports.

Detail of the inlaid shell on the fallboard of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29.

Detail of the eagle inlaid on the prospect door of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29. (Courtesy, White House Historical Association; photo, Bruce White.)

Composite detail showing the front and rear foot blocking and base construction of the desk-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 29.

Composite detail showing the front and rear foot blocking and base construction of the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left front foot on the secretary-and-bookcase illustrated in fig. 30. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the Old Senate Chamber, Maryland State House, Annapolis, Maryland, 1772–1779. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This space served as the senate chamber from 1779 until 1906. The illustrated furnishings represent a combination of eighteenth-century objects made in Shaw’s shop and twentieth-century pieces made in the shop of Baltimore cabinetmaker Enrico Liberti.

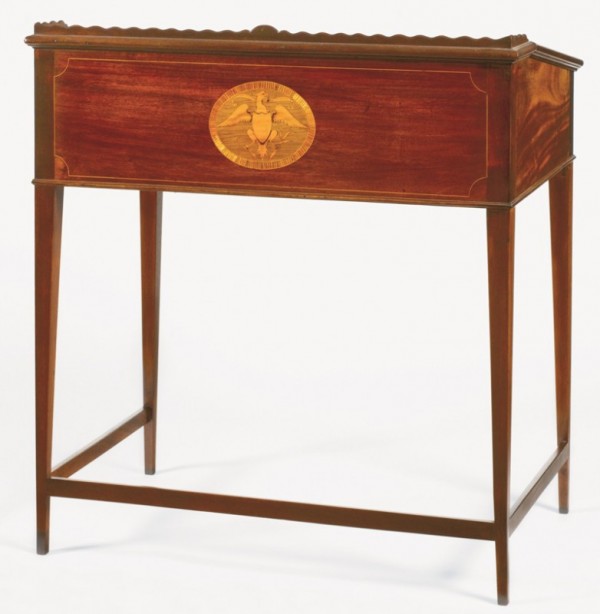

President’s desk probably made by William Tuck in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar. H. 38", W. 35 1/2", D. 21 1/4". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the label on the desk illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the inlaid eagle on the desk illustrated in fig. 39. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Desk made in the shop of John Shaw, Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1797. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with tulip poplar and yellow pine. H. 35", W. 24 1/2", D. 21". (Collection of Charles Heyward Meyer; photo, William Voss Elder III and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis [Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983], p. 133.)

Detail of the label on the desk illustrated in fig. 42. The signature on the label reflects the work of Washington Tuck when the desk was repaired in Shaw’s shop in 1801.

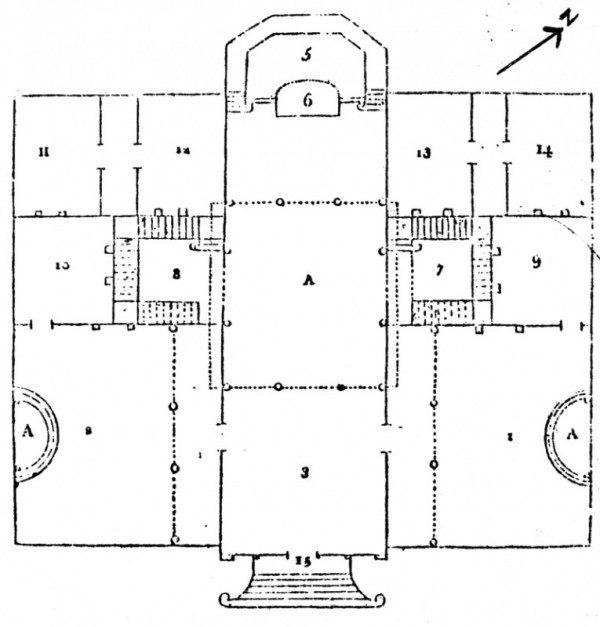

“The Ground Plan of the State-House at Annapolis,” The Columbian Magazine, February 1789. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, State House Graphics Collection.) Known as the “Columbian Plan,” this document indicated the position of the senate and house of delegates chambers and committee rooms, the general court (abolished in 1805 and its jurisdiction replaced by the court of appeals), and the record offices of the chancery court, general court, land office, and register of wills on the first floor. Located on the second floor were the council chamber (above the senate chamber), auditor’s chamber (above the house chamber), two jury rooms for the courts, and the repositories for arms above the record offices. The floor plan was classically Georgian, with the senate chamber to the right of the main door and the house of delegates chamber to the left. The two chambers were the same size and mirror images of each other, with raised podiums or “thrones” for the president and the speaker in the center of the rooms, and a visitor’s gallery at the back of each chamber.

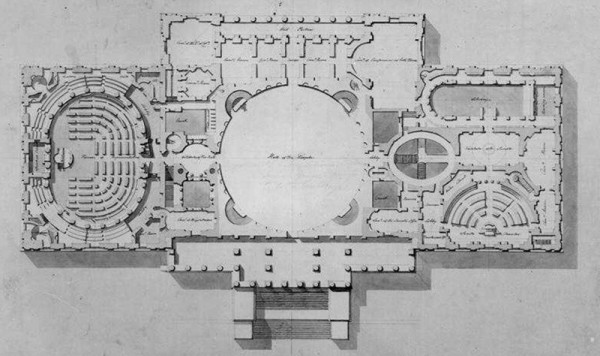

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, “Plan of the Principal Story of the Capitol, U.S.,” Washington, D.C., 1806. Graphite, ink, and watercolor on paper. 19 1/2" x 29 3/4". (Courtesy, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.) William Tuck likely saw the semicircular, tiered layout of the House of Representatives’ chamber on the left when he visited the Capitol in 1807. Latrobe depicted the furniture in the House chamber as a combination of straight and curved desks.

Speaker’s desk made in the shop of William and Washington Tuck, Annapolis, Maryland, 1807. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, and dark and lightwood inlay with yellow pine. H. 32 3/4", W. 36 1/4", D. 23". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Choate, 63.12, © 2007, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Front view of the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

Detail of the inlay on the right rear leg of the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

Detail of a wooden knob on the desk illustrated in fig. 46.

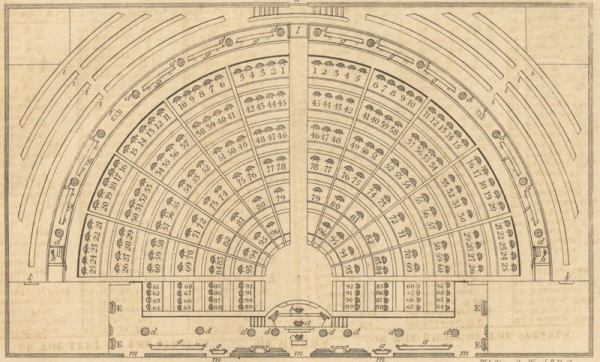

“Hall of the House of Representatives,” from Peter Force, National Calendar, 1823. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.) The furnishing scheme of the house of delegates chamber in Annapolis closely resembled that of the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C., in which straight desks were placed to the sides of the dais, while curved desks were symmetrically arranged in front of the speaker.

Late-nineteenth-century photograph showing Washington Tuck’s house on State House Circle, Annapolis, Maryland, 1820–1821. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, George Forbes Collection.)

G. W. Smith, The State House at Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1810, illustrated in Morris Radoff, The State House at Annapolis (Annapolis: Hall of Records Commission of the State of Maryland, 1972), p. 32. This image shows the State House as it probably appeared soon after the completion of the Tucks’ 1807 commission.

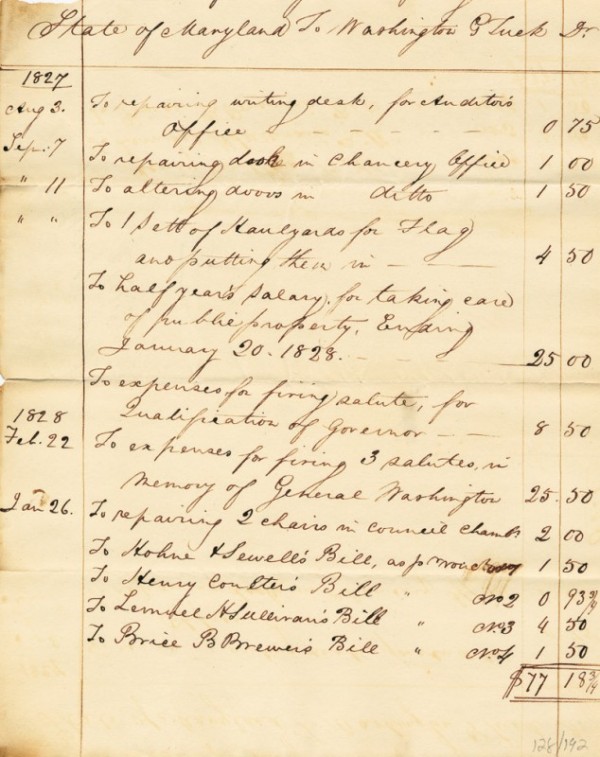

Invoice submitted by Washington G. Tuck to the state of Maryland, 1828. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Maryland State Papers.) Washington Tuck submitted this invoice for a range of services he performed between August 3, 1827, and February 22, 1828. While Tuck commonly repaired furniture in the State House (he received three separate payments for repairing “writing desks,” desks, and chairs during this six-month period), he also completed maintenance projects such as “altering doors” and replacing the halyards for the flag on the dome. The inclusion of payments for “taking care of the public property” and for firing celebratory salutes—a requirement of the state armorer—is common in these invoices, as are the payments to Tuck on behalf of four contractors.

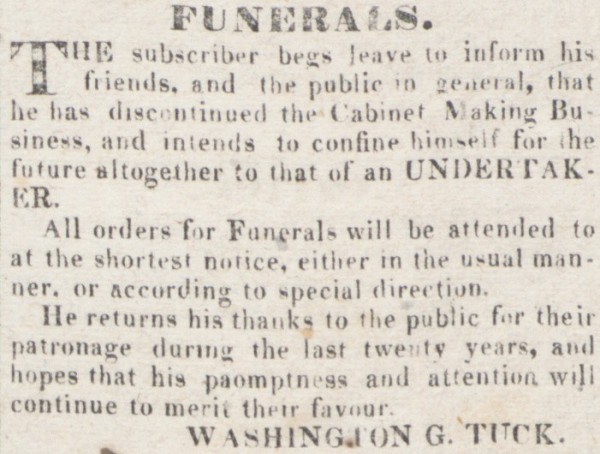

Advertisement by Washington G. Tuck in the Maryland Gazette, June 12, 1834. (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives.)

E. E. Zerlantz, Annapolis, Capitol of the State of Maryland, 1838. Photograph of an engraving. 6 5/8" x 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Maryland State Archives, Special Collections, George Forbes Collection.) This engraving shows the State House (center) as it appeared when Washington Tuck retired from public service. Romantic views of Annapolis were common throughout this period, although it is clear that little of the city’s landscape had changed since the end of the Revolution.