Door panels from a shrank made for Emanuel and Mary Herr, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768, Walnut with tulip poplar; sulfur. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The design and execution of the panels show the hand of a highly component craftsman: the inletting is crisp and even, with no knife overruns or visible tool marks. While most of the cartouche is knife-cut, tight curves were set in with specific curved gouges, confirmed by the repeated radii throughout. Most feathers on the birds are in a thumbnail style with two gouge cuts used to form the chip; the smaller feathers on the head of the large bird are punched with a triangular tool. A tracing from the right-hand door cartouche overlaid on the left indicates that the designs were transferred from a full master or half-master template for the major areas of the design. Insignificant variations between the quadrants of the cartouches are accounted for by shifting the pattern during transfer or by variations in cutting the channel.

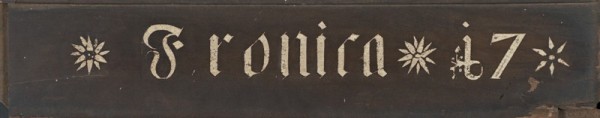

Schrank frieze fragment, possibly Pennsylvania, 1750–1799. Walnut; sulfur. (Courtesy, Alan Andersen.) The sulfur inlay, unobscured by later finishes, highlights the color shift in period sulfur inlay from yellow when new, to white when aged. The black specks visible in the white field occur as finish and grime collect in pits formed when water vapor rising out of the wood is captured in the solidifying sulfur. These inclusions are a good indicator that the inlay is sulfur and not paste.

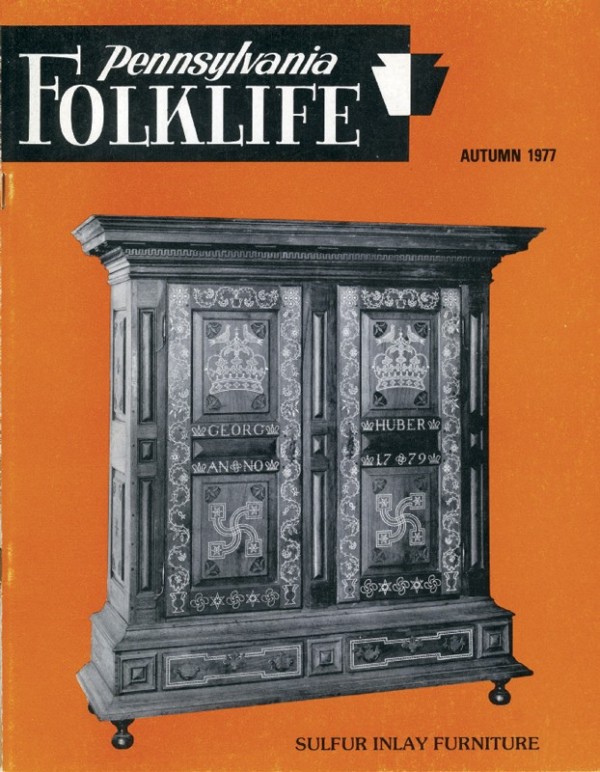

Cover of Pennsylvania Folklife (Fall 1977) featuring the Georg Huber schrank. Monroe Fabian’s article, “Sulfur Inlay in Pennsylvania German Furniture,” in this issue was the most accurate source of information on sulfur inlay at the time, utilizing analyses carried out at the Smithsonian Institution.

Valuables chest, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1773. Walnut with tulip poplar; sulfur and white composite repairs. H. 7 1/4", W. 14 3/4", D. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The central design for this small box was generated with a compass and straightedge, witnessed by the pivot points. The flower designs, slightly varying because of inletting, are from a template. The yellow tint on the top is due to a thick resin coating and stands in contrast to the chalk-white color on the tulips, which have a sparse and likely original coating.

Splint matches, origin and age undetermined. White cedar; sulfur. L. 4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) A riven white cedar splint dipped in molten sulfur makes a nonstrikable match that carries a flame once ignited.

Corner cupboard, possibly Pennsylvania, 1780–1810. Walnut with sulfur inlay and poured pewter decoration. H. 89 1/2", W. 50 1/2", D. 40 1/2". (Courtesy, Skinner, Inc.)

Detail of the decoration on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 6. The star pattern was defined with a straight chisel, showing out-of-line cuts that disrupt the straight ray with a jag. This indicates that the pewter was poured rather than cut from sheet goods. Pewter fills voids just as sulfur does, but it must be filed to level the soft metal.

Tombstone, St. Luke’s Lutheran Cemetery, Carroll County, Maryland, 1793. Slate; sulfur. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.) Many of the tombstones are sculpted in baroque profile designs with inlaid sulfur highlights. Germanic designs found on sulfur-inlaid furniture are common.

Detail of a tombstone from St. Luke’s Lutheran Cemetery, Carroll County, Maryland, 179. Slate; sulfur. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.) The deeply cut pinwheel design has sloping sides on the interior. It appears that the molten sulfur fill was intended to stop below the surface of the stone, thereby highlighting the finely crafted edge.

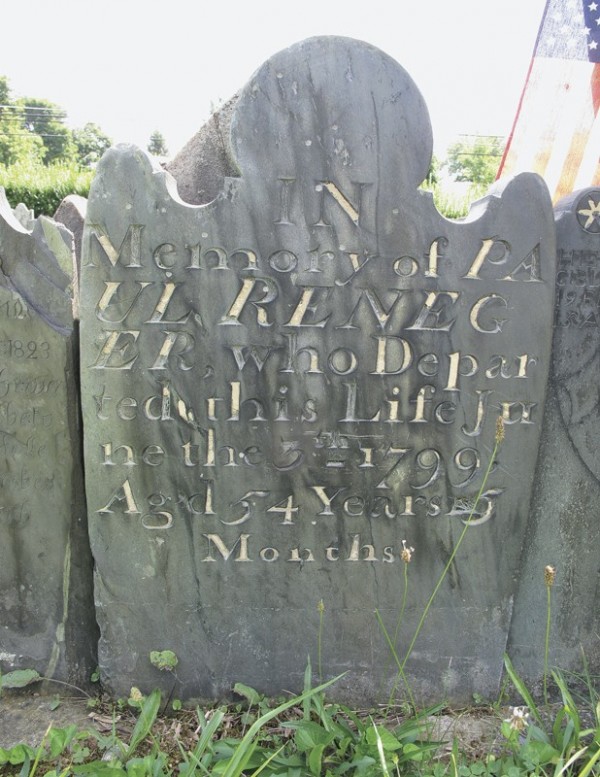

Tombstone from St. Mary’s Union Cemeteries, Carroll County, Maryland, 1799. Slate; sulfur. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.) German or English inscriptions are found on all of the tombstones in this group.

Tombstone detail from St. Mary’s Union Cemeteries, Carroll County, Maryland. Slate; sulfur. (Photo, Brenda Hornsby Heindl.) Sulfur poured into stone tends to level without bubbles.

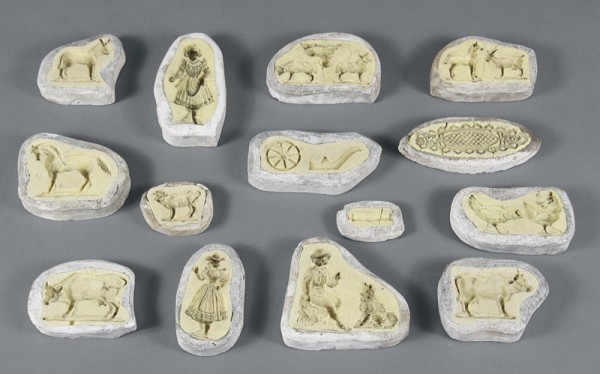

Confection molds, date and origin unknown. Sulfur; plaster. (Courtesy, Mercer Museum.) These molds, which were acquired from the Thomas Mills Company, established in Philadelphia in 1866, are probably European. The brittle sulfur cannot stand up to repeated use or environmental extremes without chipping and cracking.

One of the molds illustrated in fig. 12. This mold illustrates crossover between the carver and the mold maker. Curved gouge cuts define portions of the design.

One of the molds illustrated in fig. 12. Animal motifs are common on confection molds and decoration on American sulfur-inlaid furniture.

Butter or cookie mold, possibly Pennsylvania, 1813. Conifer. Diam. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This reverse-carved mold uses patterns and a letter style common to sulfur-inlaid designs.

Router plane, European or American, date unknown. Lignum vitae; iron. L. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) Small router planes allowed rapid clearing of waste between the incised borders of larger designs intended to receive molten sulfur.

Procedures used in the production of a scaled down, replica panel with sulfur inlay. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The pattern is transferred to the wood using a printed image with carbonized paper. Sooting the reverse of a drawing in period work would produce a similar outline when traced. Pricked patterns using pounce powder could also transfer a design. The initial outline inletting is done freehand with a knife, while two separate curved gouges cut the thumbnail feather motif. A single gouge with an elongated, tapered cutting edge is rolled to incise slightly varying curves.

Detail of the chest façade illustrated in fig. 29. Inletting for this design was made using a knife, possibly in conjunction with a V-shaped gouge. The bottom channel is smooth from the sharp cutting edge. A knife and a straight chisel were likely used for other areas and waste removal.

Detail of the Germanic numeral “1” on the chest façade illustrated in fig. 29, showing the knife and gouge work. The chip of walnut embedded in the molten sulfur is probably waste that strayed into the molten sulfur pour. This can occur when pared-off hardened sulfur is remelted.

Detail of the Germanic numeral “8” on the chest façade illustrated in fig. 29, showing knife and chisel work. The aged sulfur is white and does not have bubble pitting. The sulfur may have been near its melting point—only slightly above the boiling point of water—so less water vapor was driven out.

Detail of fig. 17, showing the gouge made "thumbnail" cuts and straight knife cutting.

Overall of fig. 21, showing the knife and gouge carving.

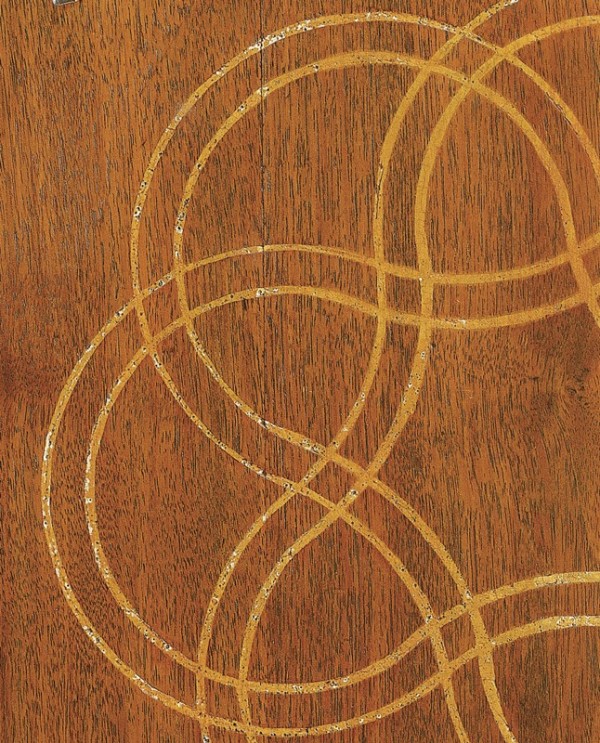

Detail of a lower door panel of a schrank made for Emanuel and Mary Herr, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1768. Walnut with tulip poplar; sulfur. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The knotwork pattern is compass-generated. A single or double cutter on the end of the compass beam could have described the outline before waste removal.

Detail of figure 17 during the sulfur inlay process. Solidified sulfur must be pared away with an edge tool or scraper. The hardened sulfur is abrasive and quickly dulls the tools. The area of lighter sulfur is due to overpouring. The trail, fully hardened, but still crystallizing, has a deeper color. Small details like the feathers can be “dotted in” with liquid sulfur.

The completed design illustrated in fig. 17, poured and scraped smooth. This image shows the replica panel (with a shellac finish) after cycling in an artificial aging chamber at the Winterthur Museum.

Molten sulfur poured from a ceramic crucible is difficult to control and often overpours.

A slow charcoal fire melts the sulfur with stirring. Careful melting at the lowest possible temperature is important as the sulfur begins to become more viscous above 300 degrees. Away from the heat the sulfur hardens quickly and must be poured without delay.

Detail of the chest façade illustrated in fig. 29.

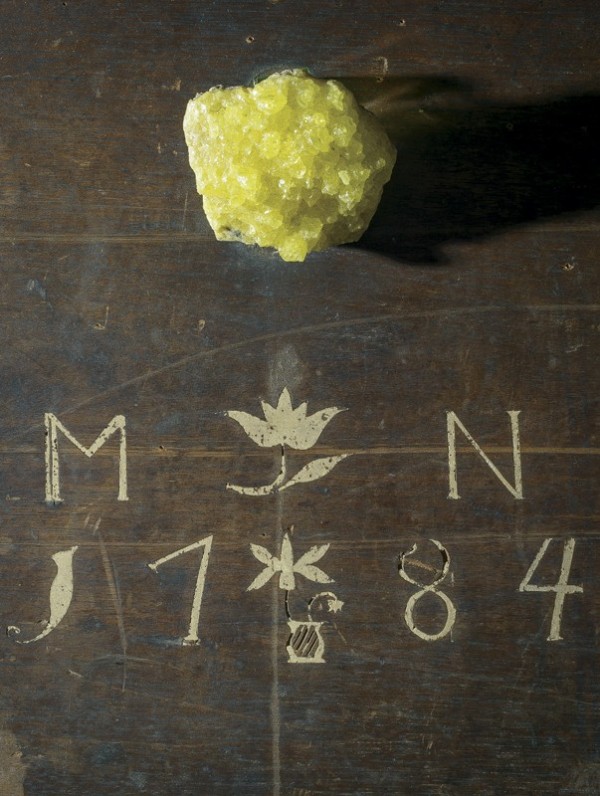

Chest façade, probably southeastern, Pennsylvania, 1784. Walnut; sulfur (yellow cave-sulfur crystals from Mexico). (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The sulfur crystals are formed as a result of bacterial action on organic material leached through the soil and crystallized on limestone from a cave roof. They show the natural bright yellow sulfur color in contrast to the aged sulfur inlay.

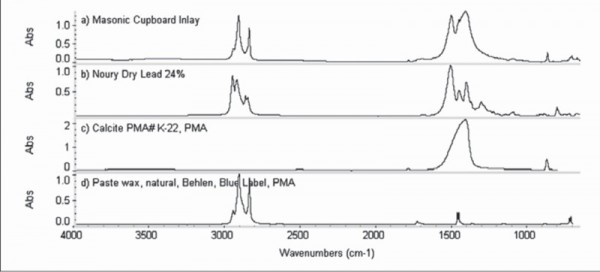

FTIR results for white inlay on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 31.

Corner cupboard, Bertie County, North Carolina, ca. 1795. Walnut with cypress; white lead, chalk and linseed oil filler. H. 103 1/4", W. 50", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) The inlay material for the tympanum cupboard was thought to be sulfur, but analysis indicates that it is white lead putty.

Detail of the putty inlay on the corner cupboard illustrated in fig. 31.

Detail of the inlay on a tall case clock, Reading, Pennsylvania, 1801. Birch with pine; white and colored gesso type inlay. H. 95 1/2", W. 21 3/4", D. 11". (Courtesy, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.) The composite inlay on this case has components similar to gilder’s gesso. Previously published as being wax, the inlay is unusual for its multicolor rendering.

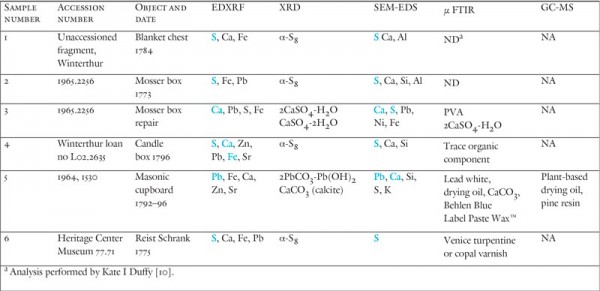

Instrumental analysis data for eighteenth-century inlays and repairs. Major elements found by EDXRF and SEM-EDS listed in blue. ND indicates no organic compounds were detected. NA indicates not analyzed.

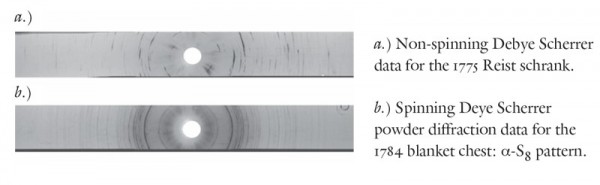

XRD diffraction patterns used to identify smaller crystal domains found in aged sulfur inlay.

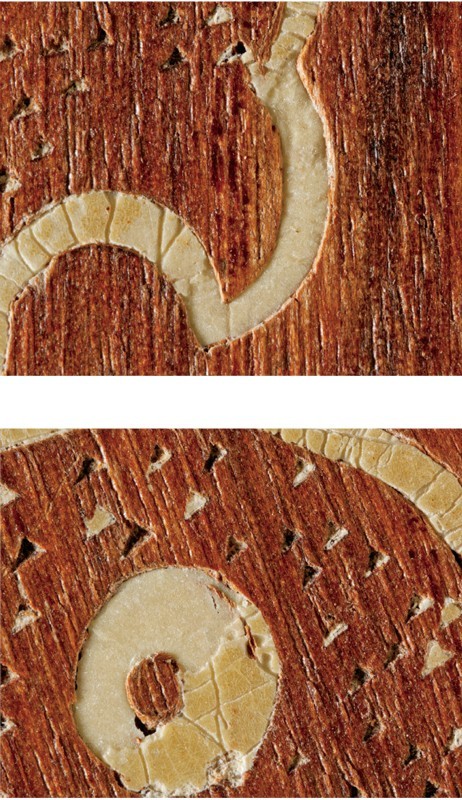

Close-up of the replica panel illustrated in fig. 25, showing spalling and color shift as a result of artificial aging.

Close-ups of the replica panel illustrated in fig. 25, showing spalling and color shift as a result of artificial aging.