Detail of Henricus Hondius’s Nova Virginiae Tabula, Amsterdam map of the Virginia colony and the Chesapeake Bay, 1630. 15 1/2 x 19 1/2". (Geographicus Rare Antique Maps Cooperation Project.)

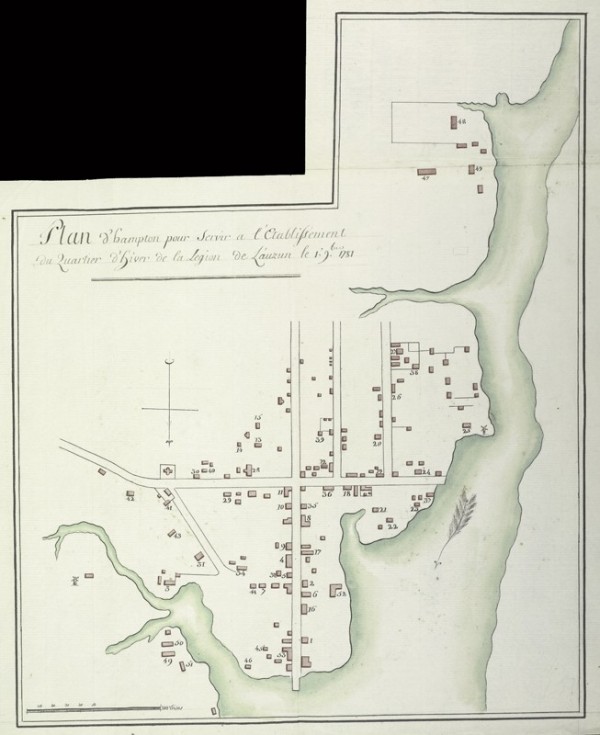

Plan d’Hampton pour servir a l’Etablissement du Quartier d’hiver de la Legion de L’auzun, le 1 9bre, 1781 (Plan of Hampton [Virginia] to be Used for Establishing the Winter Quarters of Lauzun’s Legion. 1 November 1781). 15 3/8" x 12 3/8". (Princeton University Library Collection.)

An 1864 photograph of the Grand Contraband Camp in Hampton, Virginia. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) The camp was the first self-contained black community in the United States, with a population of 9,000 by 1865.

Photograph of fieldwork conducted by archaeologists from the College of William and Mary on the future site of Hampton’s Air and Space Center, 1988. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Various seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trash pits containing large quantities of ceramics, glass, and animal bone can be seen.

Photograph of the excavation of an eighteenth-century cellar at the Goodyear-Kramer Tire Store lot on the corner of South King Street and Settlers Landing Road, 2006. The Hampton Air and Space Museum is in the background. (Courtesy, James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc.)

Photograph of a ca. 1690–1710 Westerwald stoneware mug moments after it was found in the fill of a seventeenth-century tavern cellar by archaeologists from the College of William and Mary, 1989. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

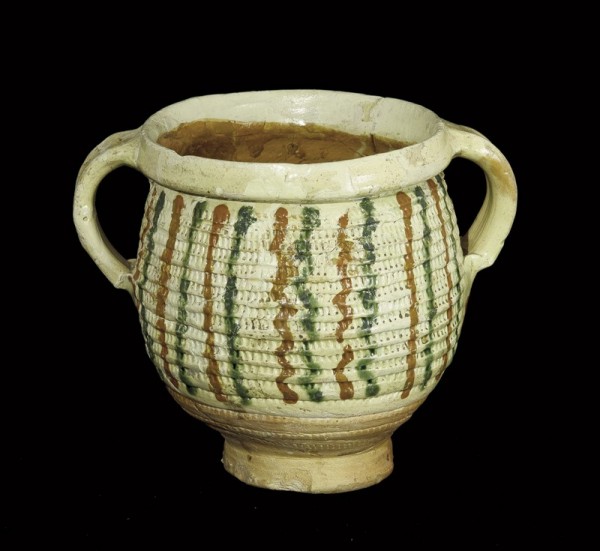

Weser slipware two-handle pot, Germany, 1590–1600. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, St. John’s Episcopal Church, Hampton, Virginia; photo, Robert Hunter.) Weser ware was made in a number of production sites between the Weser and Leine Rivers in northern Germany. This example is distinguished by the addition of the unusual rouletted decoration.

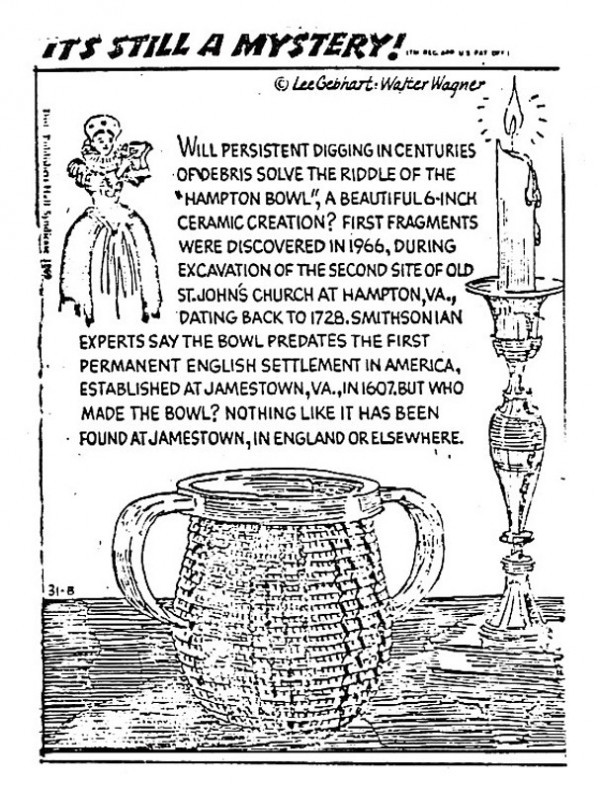

Illustration from Lee Gebhart and Walter Wagner, It’s Still a Mystery (New York: Scholastic Book Services, 1970).

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 7/16". (Hampton University Museum; photo, Colonial Williamsburg.)

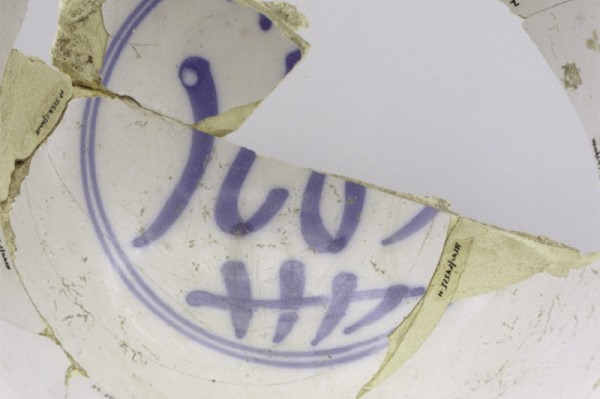

Reverse of the dish illustrated in fig. 9.

Jug, North Devon, England, ca. 1660–1670. Sgraffito slipware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, attributed to William Oliver, North Devon, England, dated 1668. Sgraffito slipware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Punch bowl, possibly Brislington, England, or Netherlands, 1689. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9 1/2". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing 1689 date inscribed inside the bowl illustrated in fig. 13.

Salt, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1690–1700. Slipware. W. 4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Michelle Erickson, Hampton Salt, 1990. Slipware. H. 2 3/4". (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Facsimiles of the Staffordshire salt illustrated in fig. 15, showing the conjectural base of the original.

Trencher salt, Hugh Quick, London, ca. 1674. Pewter. (The British Museum, Portable Antiquity Scheme, www.finds.org.uk, Unique ID: LON-A83118.) Note the hexagonal shape.

Mugs, Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1690–1701. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest 4 3/16". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

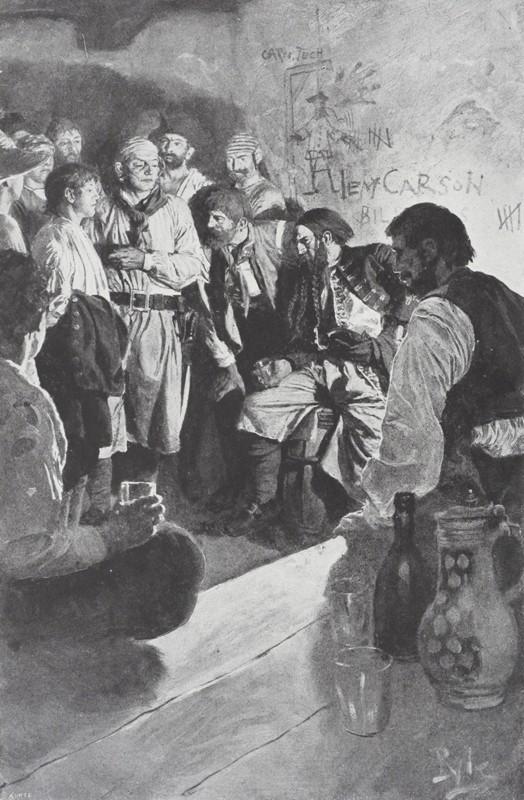

Illustration from Howard Pyle, The Story of Jack Ballister’s Fortunes (New York: The Century Co., 1895), p. 136. Pyle’s narrative recounts the adventures of a young man who was kidnapped in 1719 and carried to the plantations of Virginia, where he fell in with Captain Edward Teach, known as Blackbeard. Note the Westerwald stoneware jug in the right foreground.

Teapot, attributed to William Greatbatch, Staffordshire, England, 1760–1765. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) William Greatbatch was the most talented Staffordshire designer and maker of ceramic models and molds during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Waste bowl, Staffordshire, England, 1760–1770. Lead-glaze earthenware. D. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1775. Slip-decorated creamware. L. of fragment 5". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1775. Slip-decorated creamware. L. 7 3/16". (Courtesy, The Mint Museum, Museum Purchase: Delhom Collection, 1965.48.1677.)

Dish, Staffordshire, England, 1820–1830. Pearlware. W. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Transfer-printed in the so-called Russian Scenery pattern.

Plate, possibly Davenport, Staffordshire, England, 1820–1830. Pearlware. D. 10". Marks: impressed anchor mark on the reverse; printed “SEMI CHINA” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) An antique example of the so-called Russian Palace pattern. It differs from the excavated example illustrated in fig. 24, suggesting that more than one manufacturer copied the pattern.

Jug, probably Staffordshire, England, 1850–1860. Whiteware. H. 6 1/4". (Courtesy, Hampton History Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.)

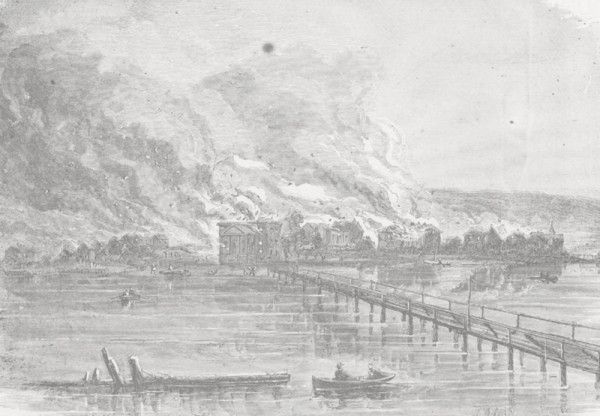

“The Burning of Hampton by the Rebel Forces under Colonel Magruder,” Harper’s Weekly, August 31, 1861, p. 550.