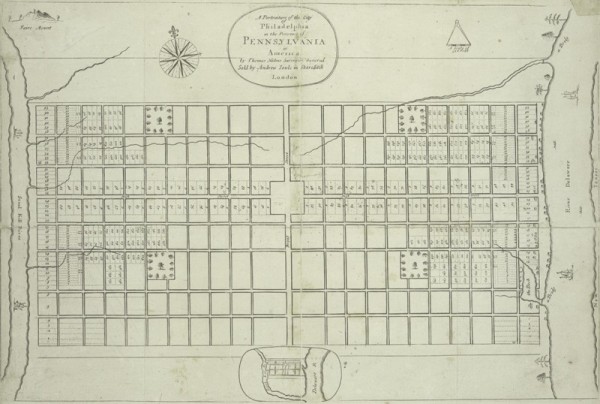

Thomas Holme, A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania in America, London, England, 1683. 11 1/2 x 17 1/2". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

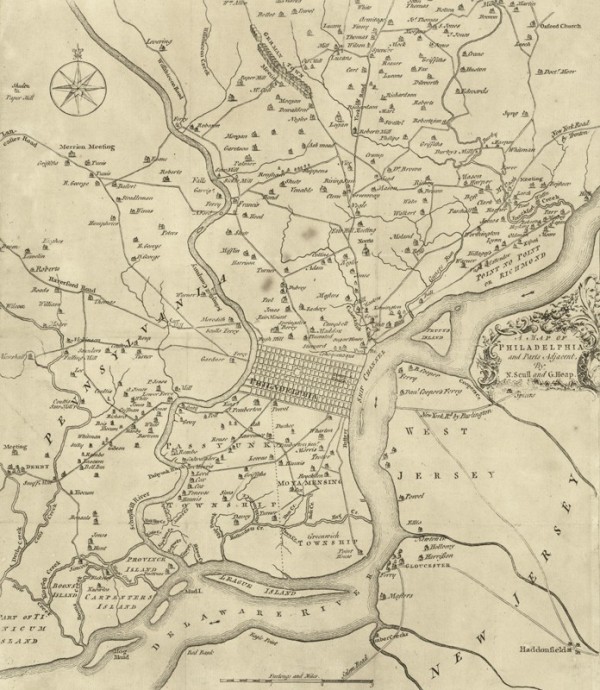

Nicholas Scull (1686?–1761?) and George Heap (act. 1715–1760), A Map of Philadelphia and Parts Adjacent, reproduced from Gentleman’s Magazine 23 (1753): 373. 13 3/4 x 11 13/16". (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, LCCN 2010587015.) Thomas Holme’s original grid plan for the city (see fig. 1) is intact in the center of the map, illustrating how much Philadelphia and her immediate hinterlands had grown by the mid-eighteenth century.

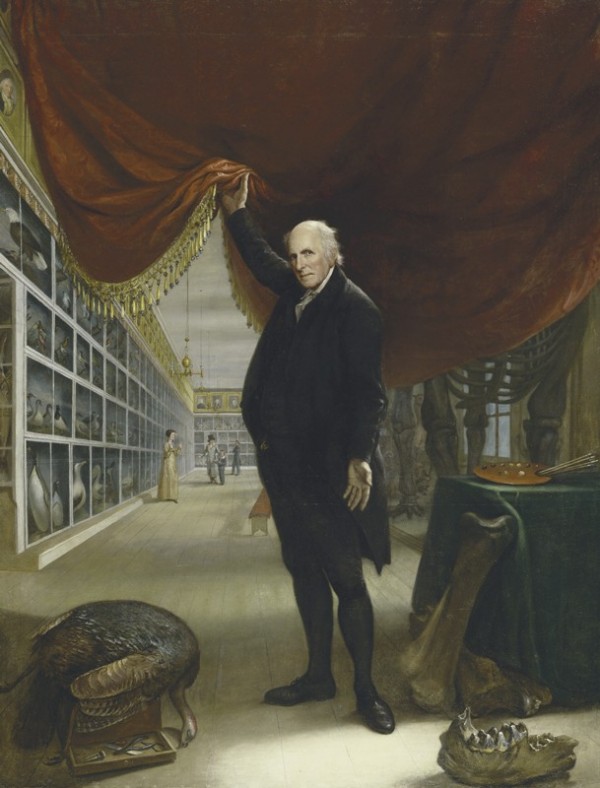

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Artist in His Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1822. Oil on canvas, 103 3/4 x 79 7/8". (Courtesy, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison.) The first of its kind in America, the Philadelphia Museum, which Peale founded in what is now Independence Hall, embodied the civic, intellectual, and artistic achievements of Philadelphia. Its exhibits captured the essence of enlightened thought and the sophisticated spirit of the new nation.

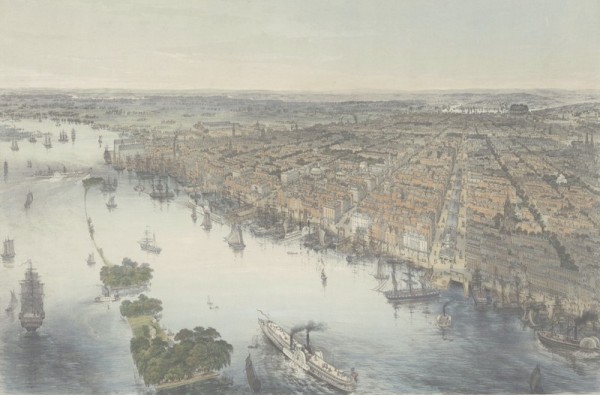

John Bachmann, Bird’s Eye View of Philadelphia, Drawn from Nature and on Stone by J. Bachmann, ca. 1850. Printed by Williams and Stevens, New York, New York. Hand-colored lithograph, 27 x 18 1/4". (Courtesy, Free Library of Philadelphia.) Philadelphia had grown well beyond its original boundaries by the mid-nineteenth century. Manufacturing was centered on the banks of the Delaware in Kensington, just north of the city center and along the Schuylkill River to the east.

Volunteers at the Independence National Historical Park Archaeology Laboratory mend red earthenware fragments recovered from one privy. Note the variety of decoration and form exhibited by this ceramic assemblage. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)

Partially excavated privy from the National Constitution Center site, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2003. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This photo shows a trash layer containing discarded eighteenth-century domestic goods, such as ceramics, glass, and small household items. The scale in the photo is three feet in length.

Charger and bowl, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, second quarter of eighteenth century. Slipware. D. of charger 14 3/4", H. of bowl 2 5/16". (Courtesy, Chris Rowell; photo, Deborah Miller.) The charger is reminiscent of English Staffordshire-type slipware that is commonly found on American colonial archaeological sites. The form and decoration of the bowl are consistent with wasters discovered in a rubbish pit behind George Peter Hillegas’s property on Second Street. The use of copper oxide was introduced after the arrival of German and, in the case of the Hillegas Brothers, French potters to the colony in the 1720s.

Charger, bowl, dish, and pan, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late eighteenth century. Slipware. D. of charger 15". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Vessels of diverse forms with multiple applications of straight and wavy lines, sometimes combined with splotches of copper oxide, are characteristic of “Philadelphia Style” wares. Examples like these number in the tens of thousands on Philadelphia archaeological sites.

Jug, Anthony Duché, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1720–1764. Salt-glazed stoneware with iron oxide slip. H. 9 3/4". Impressed “AD” below handle terminal. (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This jug was excavated from a privy at Front and Dock Streets, where the Society Hill Sheraton Hotel is now located.

Chamber pots, Anthony Duché, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1724–1764. Salt-glazed stoneware. Impressed “AD” at base of handle. H. 6" (all vessels). (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These five chamber pots are decorated with stamped designs infilled with cobalt. The fleur-de-lis on the center vessel is a reminder of Anthony Duché’s French heritage.

Pan, southeastern Pennsylvania (likely Philadelphia), ca. 1730–1765. Slipware. D. 14". (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This pan might have played a ceremonial role in diplomatic negotiations held at Stenton between James Logan and delegates from the Six Nations in 1736 and 1742.

John Simon, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maguas, London, England, 1710. Mezzotint. 16 5/16 x 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, museum purchase, 1970.0005 A.) This is the one of a set of four mezzotints after full-length oil protraits commissioned of John Verelst by Queen Anne. Contrmporary images like this one may have served as the model for common objects like the slipware bowl excavated at Stenton (fing. 11).

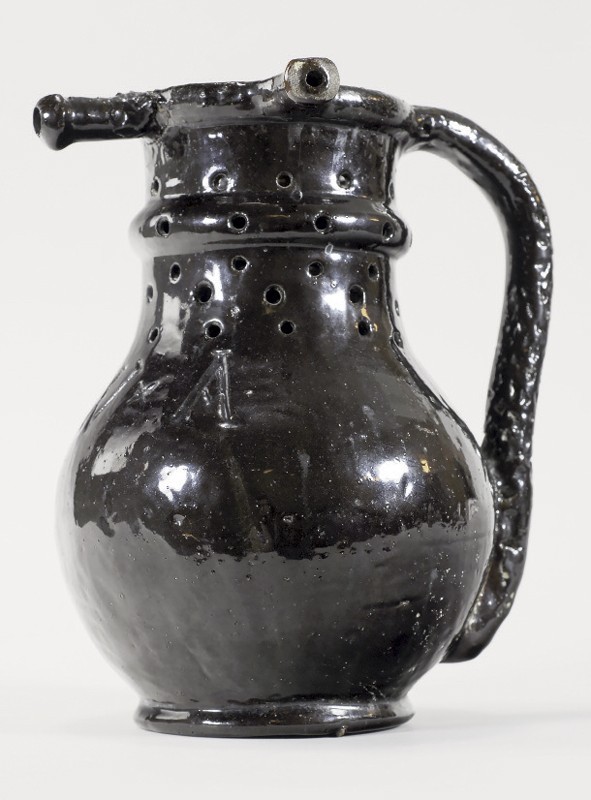

Puzzle jug, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1747. Red earthenware with manganese glaze. Incised “WA” on front. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Found in the privy near the home of William Annis, the initials suggest that this striking puzzle jug was made for him but discarded intact, probably because a manufacturing flaw on the handle made it unusable.

Plate, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1735–1748. Porcelain. D. 9". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) The central pineapple is flanked by a branch of cloves on the left and a nutmeg on the right.

Teapot fragments, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1755–1785. White salt-glazed stoneware with a Littler-Wedgwood blue glaze. (Courtesy, State Museum of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; photo, Deborah Miller.)

Tea table, set with English white salt-glazed and cream-colored earthenware teapots and Chinese porcelain teawares, ca. 1725–1760. (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Jeff Story.) At least twelve teapots and dozens of teabowls and saucers were excavated from a cistern at Stenton, the ca. 1730 home of James Logan in Germantown. For families like the Logans, tea drinking solidified social and political networks while demonstrating participation in polite culture.

Cooking pot, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, late eighteenth century. Earthenware. (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) Colonoware is exceedingly rare on archaeological sites north of the Chesapeake, and fewer than one hundred examples have been excavated in Philadelphia. This partial vessel is the largest and most intact example to be recovered in the city to date.

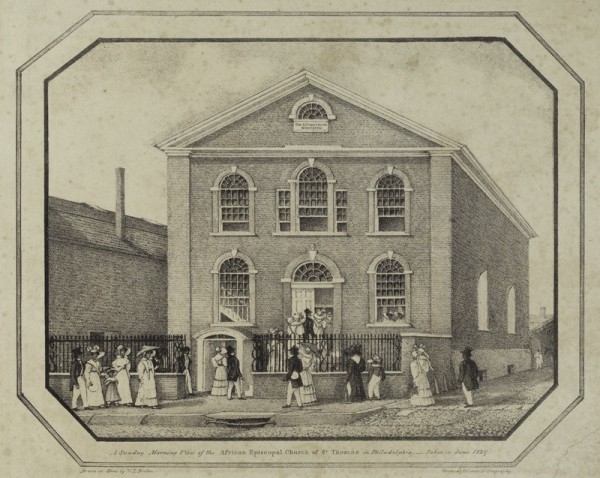

William L. Breton (ca. 1773–1855), A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. . . Taken in June 1829 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Kennedy & Lucas Lithography, 1829). Lithograph on paper. 9 3/4 x 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) In 1787 former slaves Richard Allan and Absalom Jones founded the Free African Society, one of America’s first societies dedicated to improving the lives of newly freed slaves. By the nineteenth century, independent churches like the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and Mother Bethel A.M.E. were the core of the free African-American community in Philadelphia.

Two sauceboats, saucer, and teabowl, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of sauceboats 3", D. of saucer 5 1/2", base of teabowl, 1 3/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) These four examples of Bonnin and Morris porcelain were excavated from two different sites at Independence NHP. The sauceboats are believed to have been owned by Caleb Cresson, a wealthy Quaker who originally developed what is now the National Constitution Center site. The ownership of the saucer and teabowl, both of which are marked “P” on the base, is unknown.

Saucer, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Matthew and Melissa Dunphy; photo, Deborah Miller.) This saucer, along with a small punchbowl, was recently excavated from a privy at 103 Callowhill Street in the Northern Liberties. The punchbowl is marked "P" on the base. They are the most recent examples of Bonnin and Morris to be discovered.

Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), Still Life of Fruit, Pitcher and Pretzel, 1810. Oil on wood panel, 11 3/4 x 13". (Courtesy, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York; photo, Eric W. Baumgartner.) In 1808 Peale’s father, Charles Willson Peale, exhibited at his museum some of the first examples of Philadelphia queensware, presumably made by Alexander Trotter at the Columbian Pottery.

Philadelphia queensware vessels. D. of plate 7". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) This group highlights the diversity of form and decoration found on Philadelphia queensware

Pitchers, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1815–1820. Pearlware. Black transfer-print with enamel decoration and pink lustre. H. 6". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)

Dish, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1818–1828. Red earthenware with “Alice” inscribed in slip. D. 9". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.) In 1818 Otis and his family moved into the house at 63 Cherry Street, where they lived for almost ten years. Numerous artifacts from their personal lives were recovered from a privy that was once located behind their house, including this dish, which likely belonged to Otis’s wife, Alice.

Pitcher, Tucker and Hemphill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1826–1838. Porcelain. 9 1/2 x 7 3/8 x 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of John T. Morris, 1895.)

Pitcher and serving dish, Tucker and Hemphill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1826–1838. Porcelain. H. of pitcher 7 1/4", D. of dish 8 1/4". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Independence National Historical Park.)