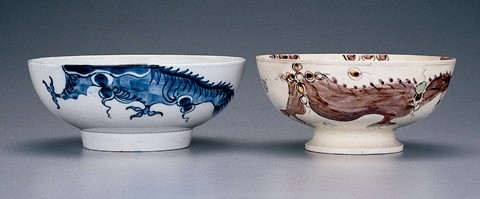

Punch bowls. Left: Staffordshire or Yorkshire, ca. 1780. Pearlware. D. 7 15/16". Right: attributed to Enoch Booth, Tunstall, Staffordshire, ca. 1745. Creamware. D. 7 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The body of the dragon starts on the exterior of the bowl and continues over the rim into the well.

Details of the interiors of the punch bowls illustrated in fig. 1, showing the head and upper body of the dragons.

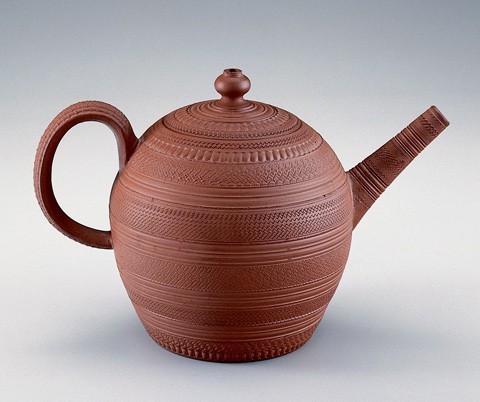

Teapot, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1770. Stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

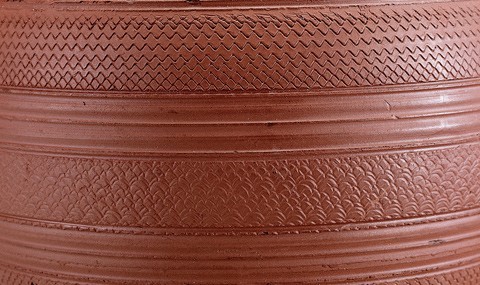

Detail of roulette decoration on the body of the teapot illustrated in fig. 3.

Detail of roulette decoration on the spout of the teapot illustrated in fig. 3.

Three ceramic objects recently acquired by the Chipstone Foundation are connected to ongoing research related to articles published in Ceramics in America. Two of these objects are eighteenth-century earthenware punch bowls decorated with underglaze dragons (figs. 1, 2). Originating on late-seventeenth-century Chinese porcelain, this motif was used extensively on English delft and, subsequently, on Worcester and Bow porcelain. Examples of delft and soft-paste porcelain punch bowls abound. Famed painter and social commentator William Hogarth owned a large, circa-1730s one of English delft.[1] Both delft and English porcelain punch bowls of this type have been found in Williamsburg excavations.[2] There appears to be no record, however, of this decorative motif on creamware and pearlware bowls, such as those illustrated here.

The creamware dragon bowl is attributed to a small group of early earthenware items made by Enoch Booth in Staffordshire around 1745.[3] The underglaze decoration was created using manganese with yellow and green highlights. The circa 1780 Staffordshire pearlware punch bowl with underglaze cobalt decoration exemplifies what has been called “china glaze,” a refined earthenware body imitative of blue-and-white porcelain.[4] These two examples demonstrate the enduring popularity of this motif, as documented on Chinese porcelain, English delft, Worcester and Bow porcelain, and, now, creamware and pearlware.

The third recently acquired object helps illustrate the economic constraints of surface embellishment on late-eighteenth-century Staffordshire red stoneware (fig. 3). As discussed in detail by Jonathan Rickard and Don Carpentier in this volume (“The Little Engine That Could,” pp. 78–99), the creation of surface decoration by engine turning was a major development in Staffordshire after 1770. At first glance this redware stoneware teapot seems to bear the characteristics typical of engine turning, but close inspection shows that the surface treatment was applied using a series of decorative rouletting wheels (fig. 4). Even the spout and lid bear roulette decoration (fig. 5). This piece is further evidence of the use of roulettes to simulate engine-turning decoration without the expense of owning the more complicated engine-turning lathe.

Robert Hunter

Editor, Ceramics in America

<CeramicJournal@aol.com>

Lars Tharp, Hogarth’s China (London: Merrell Holberton, 1997), p. 49.

John Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1994), p. 94.

Jonathan Horne, English Pottery and Related Works of Art 2002 (London: Jonathan Horne Antiques, Ltd., 2002), p. 22.

George L. Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001): 135–61.