Chair, London, ca. 1700–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 12 5/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the seat of the chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Caned armchair, London, ca. 1685–1693. Walnut and cane. H. 49 1/2". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.)

Lord and Lady Clapham dolls with original miniature chairs, London, ca. 1690–1700. Dolls: wood wrapped with wool, faces gessoed and painted, with wigs of human hair. H. 21 1/2" seated. Chairs: beech and cane. H. 20 1/2". (© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London, www.vam.ac.uk.)

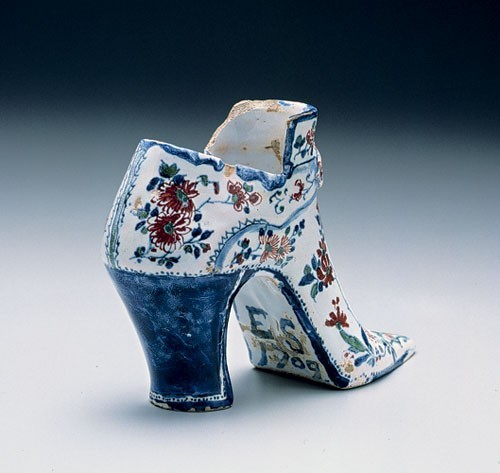

Shoe, London, 1709. Tin-glazed earthenware, decorated with the initials “ES” and the date “1709”. H. 4 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rear view of shoe illustrated in fig. 5 depicting the hand-painted initials and date on the outsole.

The Chipstone Foundation recently acquired a miniature chair made of tin-glazed earthenware that appears to be a unique survival (fig. 1).[1] This intriguing object’s playful combination of traditional pottery techniques and common chair features encourages imaginative conjecture about its origins and meanings.

Several decorative elements that appear on this ceramic chair enjoyed long-lived popularity on British ceramics of more typical form, but their combination here suggests that the piece was made in the first decades of the eighteenth century. Sponge decoration and hand-painted flowers embellished English tin-glazed earthenware for more than one hundred years beginning in the mid-seventeenth century.[2] The leaves that descend the back slats, however, are less generic. Similar stiff leaves with featherlike veining appear on several pieces associated with Vauxhall, including a tea bowl excavated at the site, a two-handled cup dated 1715, and a plaque of Queen Anne commemorating her coronation in 1702.[3] Other factories both in London and on the Continent used comparable leaf motifs, however, making a firm attribution to Vauxhall premature.[4] The humorously self-referential image of a seated lady painted on the chair seat may have been adapted from a tile design (fig. 2). The seat itself, though, is slightly trapezoidal rather than square, and the picture has not yet been found on a surviving tile or in a print source. The coiled clay elements on the crest and arms of this chair recall the handles and flourishes on posset pots, salts, and other forms made in the second half of the seventeenth century.[5] By 1700 such bold three-dimensional coils would have been somewhat out-of-date for tablewares but were well suited for this sculptural item.

This chair resembles caned chairs popular in England and its colonies from the 1680s until the 1730s (fig. 3). Like a wooden caned chair, the composition of this ceramic version culminates at the crest, where graduated coils and a half-circle painted panel evoke baroque-style carving. Similarly, the coiled elements at the ends of the arms imitate the expressive elongated volute handholds found on caned armchairs. Despite these similarities, the other structural and decorative details of this chair spring from the potter’s tradition. The slats, seat, and undercarriage are slab-built with no allusions to the shapely stiles and turned stretchers of caned chairs of the period. Similarly, the coils that create the arms themselves differ dramatically from chair arms, which were commonly a single horizontal member. Even though the full-bodied S-curve coils certainly refer to the carved volutes that decorated caned chairs, this piece is not a sculptural replica of wooden versions.

Two miniature caned chairs from this era, made of wood and cane, survive as seating for dolls (fig. 4). Wealthy women and girls often had dolls whose rich silk and lace attire matched their owner’s tastes. This ceramic chair may have been made for a doll similar to one in figure 4. Perhaps it had a mate with a gentleman painted on the seat to accompany its seated lady. Dolls and dollhouses, playthings traditionally reserved for the aristocracy, were just becoming accessible and popular among the gentry and merchant class at this time. Fittingly, caned chairs and tin-glazed earthenwares were also being made as mid-level fashion items that resembled more expensive goods but cost much less.[6]

Miniature clay replicas of other functional household items often served as humorous gifts in this era. Tin-glazed earthenware shoes commemorated marriage (figs. 5, 6). Slipware cradles given at weddings delivered wishes for fertility. This chair may have celebrated an important event, perhaps in the life of a chairmaker. Its lack of inscribed names, initials, or dates, however, suggests that it may have been intended simply as an unconventional addition to a group of blue-and-white wares displayed on a tabletop, cupboard, or overmantel shelf. Whether made for a doll, as a stylish commemorative, or for some other reason, this miniature chair records one potter’s creative combination of ceramic-making techniques, painted motifs, and a popular chair form that all appealed to the increasingly style-conscious residents of London at the turn of the eighteenth century.

Sarah Neale Fayen, Assistant Curator, Chipstone Foundation; sfayen@ chipstone.org

Garry Atkins, An Exhibition of English Pottery, exh. cat., 107 Kensington Church Street, London, March 11–22, 2003 (London: G. Atkins, 2003), no. 15.

For early sponged decoration, see Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles, exh. cat. (London: The Stationery Office, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), p. 281, no. f2, and p. 78, no. a9. For late sponge decoration, see ibid., p.137, no. b44.

Frank Britton, London Delftware (London: J. Horne, 1987), p. 71, J, upper left; Louis L. Lipski and Michael Archer, Dated English Delftware: Tin-Glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Sotheby Publications, 1984), p. 215, no. 954; Archer, Delftware, p. 406, no. L11.

For a mug at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, see Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware, p. 180, no. 810. Similar leaves also decorate French faïence from the same era; see Henry-Pierre Fourest and Jeanne Giacomotti, L’oeuvre des faïenciers français du XVIe à la fin du XVIIIe siècle..., collection Connaissance des arts “Grands artisans d’autrefois” (Paris: Hachette, 1966), pp. 84–107.

For posset pots, see Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware, pp. 200–218; for salts, see ibid., p. 348, no. 1538, and Ivor Noël Hume, Early English Delftware from London and Virginia (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), p. 29; for a drinking goblet, see Lipski and Archer, Dated English Delftware, p. 197, no. 875.

For more on dolls of this period, see Susan North, in Michael Snodin and John Styles, Design and the Decorative Arts: Britain, 1500–1900 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001), pp. 114–15. For more information about caned chairs, see Glenn Adamson, “The Politics of the Caned Chair,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 174–206. For the social use of tin-glazed earthenware, see Archer, Delftware, pp. 3–12.