Punch bowl, Paris, 1822–1828. Hard-paste porcelain, underglaze lithograph transfers, painted decoration, overglaze gilding. H. 7 1/2", D. 12". (Courtesy, The James Monroe Memorial Foundation; photo, Baltimore Museum of Art.) Although the maker of the bowl is unknown, the lithographs were designed and drawn by William Armand Barnet, possibly with assistance from Isaac Doolittle.

Detail of the eagle lithograph on the bowl illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the rose-branch portraits on the bowl illustrated in fig. 1.

Dessert plate, Pierre Louis Dagoty and Edouard Honoré, Paris, ca. 1817. Hard-paste porcelain, underglaze lithograph transfers, painted decoration, overglaze gilding. D. 9". (Courtesy, White House Collection/White House Historical Association.)

Detail of the eagle lithograph on the plate illustrated in fig. 4.

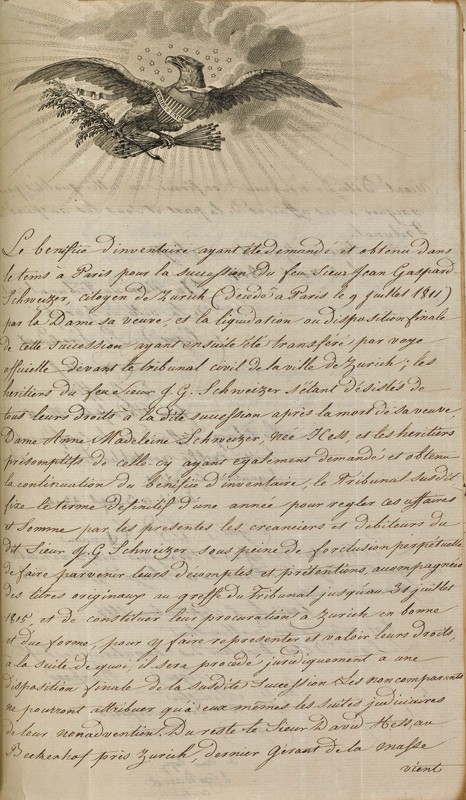

Certified copy of a consular document by Jean Rodolphe Wust concerning the estate of Jean Gaspard Schweitzer, the original signed in Geneva on August 3, 1814, and countersigned in Paris, September 3 and 5, 1814. (Courtesy, National Archives Microfilm Publication T1, roll 5, Dispatches from U.S. Consuls in Paris, 1790–1906, Record Group 59; National Archives, Washington, D.C.) Shortly after the original was signed, Isaac Cox Barnet made this official copy on consular stationery bearing the eagle lithograph.

Detail of the eagle lithograph illustrated in fig. 6.

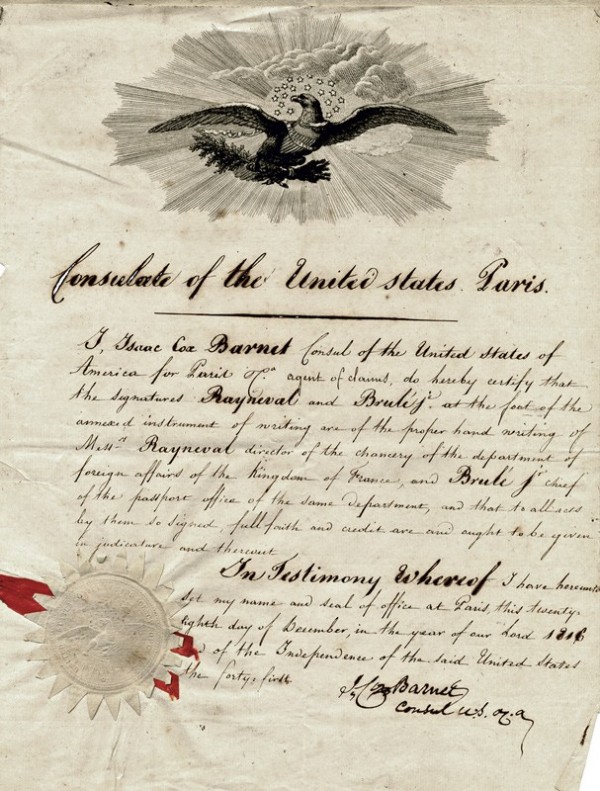

Affidavit, certifying the authenticity of a French consular document, signed Isaac Cox Barnet, Consulate of the United States, Paris, December 28, 1816. (Courtesy, Prestwould Foundation, Clarksville, Virginia.) The letterhead on which this was written bears the lithograph of an eagle signed “W. A. Barnet del.”

Detail of the eagle lithograph illustrated in fig. 8.

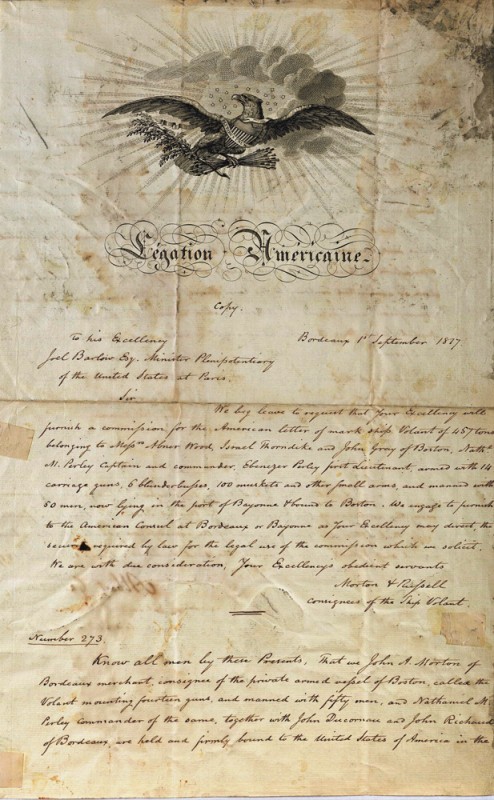

Certified Copy of a Request for Commission for the ship Volant, the original signed by Minister Plenipotentiary Joel Barlowe, September 1, 1811, this copy by Albert Gallatin, dated April 12, 1817. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College.) The lithograph, which is unsigned, is possibly by William Armand Barnet and/or Isaac Doolittle.

Detail of the eagle lithograph illustrated in fig. 10.

Coiffures de 1823, reproduced in Comtesse Marie de Villermont, Histoire de la coiffure feminine (Brussels: Société Belge de Librairie, 1892), p. 795, pl. 553.

Maria Hester Monroe (1802–1850), by Pietro Cardelli, Washington, D.C., ca. 1820. Plaster bas-relief. H. 19 1/4" x 15". (Courtesy of the James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library, Fredericksburg, Virginia, JM76.200.)

Cupid, Amelia White, Norfolk, Virginia, ca. 1829. Watercolor on paper. 9 3/4" x 8". (Colonial Williamsburg.)

A distinctive “Old Paris” porcelain punch bowl (figs. 1-3) is ornamented with four transfer prints, two depicting a rose branch with portrait busts of a woman and two children, and two depicting an American eagle. The eagles bear such a close resemblance to those on a dessert service made in 1817 by the Parisian manufactory of Dagoty et Honoré for the President’s House during the Monroe administration that they appear to have been drawn by the same artist (figs. 4, 5).[1] As with the Monroe service, hand-colored lithographs were transferred to the porcelain, but the punch bowl differs in one important respect: the ribbon draped around each eagle and flowing outward bears the inscription “W. A. Barnet, del.”

William Armand Barnet (b. 1795) was one of a small but talented group of Americans who made France their home during the early nineteenth century. Tracking his travels between France and the United States, as well as exploring his life in politics, science, and art, offers interesting new perspectives of the talented circles in which American citizens abroad often lived and worked. These pursuits also unexpectedly revealed the first American experimentation with the nascent field of lithography and brought intriguing insights into a study of the furnishing of the President’s House in Washington.[2]

Barnet was the product of an international marriage between New Jersey native Isaac Cox Barnet (1773–1833), who served as American consul to Paris from 1814 until his death, and Mademoiselle Saulnier de la Marine, daughter of the marquis de Flamarens, whose estate, the Château de Villiers-les-Maillets, was well situated at Seine-et-Marne, on the outskirts of Paris.[3]

Barnet’s parents were married in France; it is presumed the marriage took place about 1794, the year before his birth, as there are no American records of the union. In a letter of July 24, 1796, future president James Monroe, then serving his first tour of duty as minister plenipotentiary to France, wrote to Secretary of State Timothy Pickering in Washington and recommended Isaac Cox Barnet for the position of American consul to Brest, in nearby Belgium. Monroe observed that Barnet was a nephew of Elias Boudinot, who had served as president of the Continental Congress in 1782–1783, and that he would “doubtless give you more correct information of his merits than I possess.”[4]

Shortly thereafter Isaac Cox Barnet began a career in the diplomatic service that would open doors throughout his son’s life. He served as consul to Barcelona from 1799 to 1801 and to Antwerp in 1802 and 1803. In 1804 Monroe again recommended Isaac Cox Barnet for a position, this time as commercial agent for the Parisian port at Le Havre-de-Grâce, commonly known as Le Havre, where he continued in his official capacity until 1814.[5]

In 1814, when America was at war with Great Britain, then Secretary of State Monroe recommended that President James Madison appoint Isaac Cox Barnet to the prestigious position of envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Paris, a post in which he served as agent of the American government in protecting its citizens abroad and promoting its commercial interests. His relationship with Monroe placed him in a position of trust with President and Mrs. Madison, who resided in the President’s House. They relied on the consul for a wide range of duties, including the procurement of household goods needed to furnish their official and private quarters back home in America. When the British stormed Washington on August 25, burning the Capitol and the President’s House, the events triggered an intense period of rebuilding in the city that would continue for nearly a decade. This rebuilding gave the Barnet family numerous opportunities to connect with the chief executive regarding matters of furnishings. Little did they know that their old friend Monroe would one day inhabit the residence.

On May 26, 1816, Dolley Madison wrote to her friend Hannah Gallatin (1766–1847), the wife of Albert Gallatin (1761–1849), newly appointed minister plenipotentiary to France. The couple had recently arrived in Paris, and Mrs. Madison was requesting that they secure Barnet’s services on her behalf: “My dear friend I know too well . . . what your situation will be on your arrival at Paris . . . but you will find Mr. Barnet or some other knowing American who will . . . get the enclosed list of articles on good terms, & send them to Alex[andria] Washington or Norfolk this summer. . . .”[6]

The Barnets’ relationship with the chief executive proved even more crucial to the refurnishing project during the Monroe administration (1817–1825), for the new president had established ties within Paris’s flourishing artistic and political environment. Six years in France had deeply influenced the Monroes, making them acutely aware of the need to perform as cultured players on a sophisticated world stage and providing connections that would greatly benefit the young American nation. Curiously, one of the most important of these came through their eldest daughter, Eliza (1786–1835), who attended Madame Campan’s fashionable girls’ school at Saint-Germaine, near Paris. There Eliza befriended a slightly older student, Hortense Beauharnais (1783–1837), whose mother, Josephine (1763–1814), had recently married an aspiring general by the name of Napoléon Bonaparte. The Monroes later attended Napoléon’s coronation, in 1804.[7]

The Monroes’ second daughter, Maria Hester (1802–1850), was born just before the family’s second tour abroad, and like her sister became fluent in French.[8] She, too, was smitten with things Parisian, an inclination that surely was influenced in no small way by the crate upon crate of goods that the family brought home to America. They not only furnished the President’s House in French taste but also employed a French chef and usually spoke French during meals. French style had political significance not just for the family but for America as well. Indeed, the relationship between the two countries was of paramount importance, for France was seen as a valuable American ally in the two countries’ mutual desire to curb Great Britain’s ongoing aspirations around the globe.

Early in the Monroe administration William Armand Barnet reached his maturity and counted among his close friends in Paris the talented young artist, businessman, and scientist Isaac Doolittle (1784–1853), the third of that name from a distinguished line of Connecticut artisans. His grandfather Isaac (1721–1800), who married Sarah Todd, was a New Haven clockmaker well regarded for his mechanical and artistic prowess. He operated a foundry on Chapel Street adjoining Yale College and there, in 1769, constructed the first printing press made in America.[9] Isaac’s father, Isaac Jr. (1759–1821), followed in the family business,[10] and his cousin, famed silversmith Amos Doolittle (1754–1832), parlayed his skills as an engraver to become one of federal America’s most successful printmakers, known for a wide variety of historical, patriotic, portrait, and fancy scenes. In short, young Isaac Doolittle and his friend William Armand Barnet were well positioned to make their mark.

It is unclear when the Barnets first met Doolittle. Certainly, Doolittle’s family interest in printing and printmaking would have helped him forge a link with the younger Barnet who, one suspects, was already actively experimenting with lithography. Indeed, it is likely Doolittle went to Europe by the summer of 1813, perhaps earlier, to study the new printmaking process himself. However, he had other duties as well, for in a letter from Washington, D.C., to Secretary of State James Monroe on October 13, 1813, he reported that he had been captured by the British while carrying dispatches from France for Isaac Cox Barnet. On February 11, 1814, he again wrote to Monroe, this time from New Haven, once more offering his courier services, and by April was requesting reimbursement for expenses from this trip as well.[11]

Enamored by his experience abroad, Doolittle ultimately solicited a formal appointment as a commercial agent attached to America’s French consulate at Le Havre and soon found himself en route to France.[12] He went to work as personal secretary to the elder Barnet in Paris, while simultaneously fulfilling his duties as consular agent. In that capacity the young American facilitated contacts with French companies that had been commissioned to provide services or goods to American businessmen or the American government. He would assist in translating contracts, inspecting purchases, securing credit, arranging insurance, interpreting French duties, and organizing the packing and/or shipping of goods, among numerous other details.

When not engaged in official duties, Isaac Doolittle and William Armand Barnet embarked on a series of artistic and scientific pursuits with the potential to place them in the vanguard of American business abroad. Evidence clearly suggests that for a while their interests focused on experimentation with steam engines and the process of lithography—printmaking from drawings performed with grease pencils on stone. Invented in 1798 by the German Alois Senefelder (1771–1834), the new technique held great potential. “The great recommendation of lithography is the comparative cheapness and dispatch with which designs are executed by it,” noted one early proponent.[13] The process allowed subtlety of shading with greater speed, and therefore less expense, than that permitted by traditional copperplates. Furthermore, the technique fit well the rising tide of Romantic taste and the new preference for loose or more whimsical brushwork.

An 1821 article on Barnet and Doolittle’s lithographic ventures observed that they had “availed themselves of a regular course of study” on the subject while in France, yet where this took place remains in question.[14] Barnet’s father, in a letter to James Monroe in 1822, claimed that his son possessed an education “analogous to those of Capt Poussin” (the great French engineer Guillaume Tell Poussin, 1794–1876).[15] This provides an important clue not just about Barnet’s training but also about his skills. Indeed, beginning about 1815, Poussin first served the American government by designing fortifications, then canals and railway bridges. An 1831 letter from Consul Barnet to Secretary of State Martin Van Buren references the École des Ponts et Chaussées (School of Bridges and Causeways), founded in 1747, and specifically mentions the “lithographies” done there. In fact, the versatility of lithography made it well suited to the quick creation, and multiple replication, of engineering drawings. Perhaps Barnet, only a year younger than Poussin, had studied with him at the august institution and there learned the techniques.[16]

State Department archives shed significant further insight into the circumstances that surrounded the young men’s early lithographic efforts, particularly the creation of lithographed stationery for the consulate and embassy. On July 18, 1814, agitated by the disarray of the office he had inherited, Isaac Cox Barnet wrote to his predecessor, David B. Warden, on a piece of plain stationery, and complained that Warden had taken the seal with him:

There is not, that I have yet been able to discover, a single letter from the department of State . . . not a page of the laws of the United States . . . not a letter from any department of the French government . . . not even the seal of office. . . . The seal ought to be delivered over to me. If the seal was purchased out of your private fund, I will pay the value if you require it. . . .

Barnet nevertheless acknowledged that he had “adopted another” seal and would “probably never use [the old one].”[17]

Barnet’s new stationery bore a distinctive letterhead design for an American bald eagle, executed by the lithographic process. The earliest version bore no inscription and served a wide range of purposes. It first appeared on Barnet’s duplicate of a document concerning Jean Gaspard Schweitzer dated August 3, 1814 (figs. 6, 7), although Barnet probably made the copy a few days after the document was countersigned on September 3, 1814. On the next version, Consul Barnet added the words “Consulate of the United States, Paris” in glowing script, and permitted his son to take credit for the design by allowing him to place his name discreetly within the eagle’s flowing ribbon (figs. 8, 9).

A third version of the consul’s lithographed stationery, dated April 12, 1817, bears an inscription in Old English letters that identifies its use for the “Légation Américaine” (figs. 10, 11). This letterhead seal was intended for the envoy extraordinaire and minister plenipotentiary, the American ambassador to France, and does not bear young Barnet’s signature.

At present, it is unresolved whether William Armand Barnet designed the 1814 stationery, or whether his signature on the 1816 version implies that he also drew it on the lithographer’s stone. Certainly Doolittle’s exposure to his family printmaking businesses and his documented 1813 travels to France raise the likelihood that by 1814 one or both of the young men had executed the work in its entirety. Furthermore, there was a long history of printing associated not only with the Doolittle family but also with America’s diplomatic mission in Paris, one that dated back to printer Benjamin Franklin’s tenure as America’s first minister plenipotentiary to France (1777–1785). While there, Franklin had purchased a printing press that he used to great advantage, partly for his personal amusement yet also to protect the confidentiality of America’s official business during the crucial era of the Revolutionary War. Franklin’s tenure had much in common with Barnet’s service in 1814, when America was once again at war with England.[18] Regardless of the documentation, the first of this lithographic work precedes, by nearly three years, that used on the 166-piece Monroe dessert service, which was unloaded at the docks of Alexandria, Virginia, on November 11, 1817.

When Doolittle’s two-year tenure as a commercial agent expired in 1816, Isaac Cox Barnet apprised Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin that the young man had declined reappointment to the position: “He does not desire the Office,” Barnet wrote. Barnet then selected Joseph Russell, formerly a commercial agent at Bordeaux, and one John Lafarge.[19] The dual appointment was ideal in many respects, for it allowed the two men to work closely with Barnet, assisting American businesses abroad while simultaneously acquiring the multitude of furnishings needed for the President’s House, the rebuilding of which, by this point, was progressing quite nicely.

Russell and Lafarge were intricately entwined in the minutiae of furniture orders for the President’s House and are commonly credited by historians for their tremendous role in that endeavor. However, Isaac Cox Barnet, as consul to Paris, held final responsibility and also was intimately involved. He advanced personal funds on behalf of the president on at least one occasion, paying 856.75 francs for “two looking glasses.”[20] Barnet’s role also permitted him the opportunity to influence certain designs. In this respect his son’s consular letterhead was superbly timed, for it provided a stylish new eagle that could be adapted easily to any number of circumstances.

Curiously enough, among the individuals in Paris who experimented with lithography concurrently with Doolittle and Barnet were the Honoré brothers, who were intensely interested in perfecting the transfer of lithographic prints to porcelain. The Royal Conservatory of Arts and Letters, in its periodic publication Description des machines et procédés, recorded that in 1817 “sieurs Honoré et Compagnie, à Paris” had patented a process for applying lithographic images to porcelain—this scarcely a year before the order from Dagoty et Honoré for the Monroe service.[21] The use of copper-engraved prints on earthenware and soft-paste porcelain had been practiced with widespread success in England since the 1750s, but transferring lithographic prints to hard-paste porcelain required highly specialized expertise. In short, the president’s porcelain represented not only the most fashionable French design but also the most advanced technology.

Free of obligations at the consulate, Doolittle and Barnet (almost concurrently) began extensive experimentation with improvements to steam engines and, in particular, their application to ships. In 1818 they applied from France for an American patent for “certain improvements on steam boats.”[22] Doolittle’s knowledge likely grew from experience in New England, where Yale graduate Samuel Morey (1762–1843) had, in the 1790s, first outfitted a ship with an internal combustion engine for a successful venture on the Connecticut River.[23] In 1819 one John Sullivan, who for commercial purposes had purchased Morey’s patent, published a description of the engine in the inaugural issue of the American Journal of Science and Arts, a venture by Yale professor Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864), an old New Haven acquaintance of the Doolittle family. Doolittle, eager to demonstrate his mastery of the subject, penned a harshly worded article that criticized Morey’s invention as unworkable, and submitted it to the journal the following year.[24] He found himself quickly refuted by Sullivan, whose rebuttal to his argument appeared in the very same issue. If Doolittle felt blindsided, the esteemed professor would soon make it up to the young man, who was about to return temporarily to America.

Late in 1820 or early in 1821 Barnet and Doolittle moved from Paris to New York with the intention of establishing a commercial lithography business.[25] There they rented a building at 23 Lumber Street, set up their press, and offered their services to the public, ranging from ordinary job printing to book illustration. In October 1821 Silliman’s American Journal of Science and Arts announced the Doolittle and Barnet venture in commercial lithography, providing one of the first and most thorough explanations of the techniques to the American public and including examples of their work. The following year Silliman further encouraged the young men by illustrating several articles with their work.[26]

In 1822 examples of their work appeared in the popular Children’s Friend, Number III, and in The Grammar of Botany, the latter written by Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828), a British botanist and president of the Linnean Society. Printed in numerous American and British editions, only this New York imprint contains the following: “Notice to the New-York Edition . . . the beautiful and appropriate drawings . . . are specimens of American Lithography. They are from the pencil of Mr. [Arthur J.] Stansbury, and were executed at the Lithographic Press of Barnet & Doolittle, of this City.” The book may well have caught President Monroe’s attention, as the publisher, James V. Seaman, was related to the president’s in-laws, the Kortrights.[27]

In 1822, while Barnet and Doolittle were in New York working feverishly to make a success of their business, Isaac Cox Barnett had relocated to Charleston, South Carolina, residing there long enough for his name to appear in the City Directory as “Consul in the Kingdom of France, and its dependencies, Paris” and “Agent for Claims and for Seamen, in the Kingdom of France, and its dependencies.”[28] One can only surmise whether the statesman was visiting the South’s wealthiest and most cosmopolitan city solely to fulfill government obligations, or whether he also sought business on behalf of his son’s new venture. At any rate, by winter’s end the lithography business had all but failed and the consul wisely left Charleston well before the heat of summer.

Undaunted by his son’s setback, on April 29, 1822, Isaac Cox Barnet wrote from Paris to his friend James Monroe at the President’s House, apprising him of the failure of the business and informing him of his son’s anticipated work as an engineer:

My oldest Son, Wm. A. G. with Mr. Doolittle, carried the Lithographic art to the United States where it seems there is not yet sufficient encouragement, and he will soon be seeking to employ his talent in some useful branch of Engineering. His education and talent are analogous to those of Capt Poussin when he went to the United States, and he possesses the additional knowledge of Mechanics, for which he has much genius.[29]

Monroe’s response, if any, remains unrecorded, yet evidence suggests that the young entrepreneur may have focused his attention on creating the ornament for the punch bowl within a year of this letter.

Strong evidence is provided by the bowl’s lithographic figures—the portrait bust of a woman, as well as the cherub and the child’s head centered in rose blossoms that ornament the bowl’s sides (see fig. 3). The style of the woman’s hair, with its enormous curls piled high (fig. 12), first emerged in Parisian haute couture in 1823 and remained popular in fashion magazines until 1827. After that date, European society had forsaken such coiffure, even in London, where, in the spring of 1828, Pocket Magazine reported that “The . . . curls around the face . . . are not so enormous as formerly.”[30]

To fully comprehend the bowl’s historical context and William Armand Barnet’s involvement in its creation, one must also assess the significance of the form itself and of the lithographic figures that adorn it. Why did Barnet select the same eagle that he had also applied to consular letterhead and presidential china? Are the images of the woman, child, and cherub merely allegorical, or do they represent individuals that the Barnet family actually knew? In contemplating these questions one must also consider the stature of the piece to which he applied the ornamentation, for to execute a nearly flawless twelve-inch Paris bowl constructed of milky white, hard-paste porcelain with a gilt band and decorated with cutting-edge color lithographs was no minor achievement. Moreover, it would have been expensive and used in the most fashionable of households.

Given these circumstances and the serious pursuits of the Barnet family and their knowledge of diplomatic protocol, it would seem incongruous to trivialize the bowl’s symbolic eagle decoration or the technical achievement that it represented by adorning it with anonymous portraiture. This has prompted the authors to investigate one further area of research—a thorough survey of portraits that depict the Barnets’ circle, in particular the wives and children of Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson. In the end, only one individual can be said to closely resemble the woman depicted on the bowl: Maria Hester Monroe (1802–1850; fig. 13), the second daughter of James and Elizabeth Kortright Monroe. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the 1821–1822 New York lithographic venture of Barnet and Doolittle had offered the aspiring entrepreneurs a direct link to the president’s younger daughter, who recently had married Samuel L. Gouverneur in the first recorded White House wedding and then settled in Manhattan.

On either side of the woman’s portrait is an image of a child, a figure that in popular culture sometimes was interpreted as Cupid (fig. 14)—logical enough in light of the Gouverneurs’ recent marriage. However, another interpretation also seems valid. Soon after relocating, the Gouverneurs lost their first child, a daughter, who lived only briefly after her birth in 1821.[31] Their second child, a son, was born in 1822, much to the family’s delight.[32] Could the lithographic images of a woman, a child, and a cherub depict Maria, her son, James Spencer Gouverneur, and the deceased daughter? As evidence there are the post-1823 date of the bowl, the Barnets’ ties to Parisian porcelain manufactures, the Barnet family’s long relationship with the president, and the family’s proximity to the Gouverneurs immediately before the bowl’s creation—enough for the suggestion to merit consideration, even if it remains unproven. Certainly Maria Gouverneur was the closest the creative young men would get to the president during their American tenure.

Regardless of the bowl’s intended purpose or its technical sophistication, neither of the Barnets appears to have succeeded in securing Monroe’s support for government contracts beyond their diplomatic duties, although their association with Professor Silliman survived for quite some time. Through the end of the 1820s, and possibly longer, Silliman sent copies of his Journal to William Armand Barnet in Paris and occasionally exchanged letters with the family.[33] Doolittle remained in touch by translating Journal articles from French contributors for the professor.[34] Although the inconvenience of distance now dictated that Silliman turn to others for Journal illustrations, he nonetheless periodically relied on Doolittle’s New Haven kinsman, engraver Amos Doolittle, for those services.[35]

Documentation might eventually surface that makes it possible to connect the bowl irrefutably to the original owner and to verify the specific circumstances under which it was made and decorated. Even with a plethora of unproven hypotheses, however, the piece offers important insights into American history. Its relationship to the 1814 lithographic letterhead for the American consulate conclusively links William Armand Barnet to the eagle design selected for the Monroe china, and it helps to illumine Isaac Cox Barnet’s quiet but significant role in refurnishing the President’s House. And even if Barnet and Doolittle’s residence in Paris makes it unlikely that their consular letterhead will ever be considered the first American lithography, it nonetheless antedates Bass Otis’s lithographs from 1819, the first completed on American soil. As such, it pushes back to 1814 America’s initial involvement with the lithographic process and places these forward-looking men at the epicenter of its first use on porcelain shortly thereafter.[36] Each of these revelations, in its own right, establishes for the bowl a notable heritage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors extend thanks to the archivists, librarians, and staff at the Baltimore Museum of Art, James Monroe Memorial Foundation, National Archives and Records Administration, Library of Congress, Sheridan Libraries of Johns Hopkins University, New York Public Library, New-York Historical Society, New York University, Maryland Historical Society, Enoch Pratt Free Library, Morgan Library, Yale University, Princeton University, The College of William and Mary, Swarthmore College, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Towson University, Bibliothèque nationale de France, and Manufacture nationale de Sèvres, as well as the following individuals: Beth Ahern, Georgia Barnhill, Luke Beckerdite, Meghan Budinger of the James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library, Bernard Chevalier, Julie Dennis, Christina Egli, Anna Ehrdily, Janis Emery, Meaghan Emery, Dominik Guegel, Marianne Hendrix, Julian Hudson of The Prestwould Foundation, Rob Hunter, Laura Libert, Andrew Quinn, Angie Quinn, Bryan Quinn, Katherine Quinn, Sean Quinn, Tom Quinn, Cyndy Sinnott, Ann Steuart, George William Thomas of the James Monroe Memorial Foundation, Douglas Thurman, Martha Vick, Derita Williams, and James Zeender.

The bowl was first published in Marian Klamkin, White House China (New York: Scribner, 1972), p. 42. The eagle ornament on the Monroe presidential china and the bowl was also employed in 1828 for the Andrew Jackson presidential service.

Research concerning the punch bowl inevitably led to an underutilized but important resource: the archives of the State Department, which are largely overlooked in explorations of the arts associated with America’s early government. Records from the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and numerous public and private libraries helped to piece together the story.

Information concerning the elder Mrs. Barnet can be found in Charles Coleman Sellers, “Catalogue of the Society’s Exhibition of Portraits of Benjamin Franklin: January 17–April 20, 1956,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 100, no. 4 (August 31, 1956): 376; and Charles Coleman Sellers, “The Barnet Franklin,” Antiques 70 (October 1956): 354.

ALS James Monroe in Paris to Secretary of State Timothy Pickering in Washington, D.C., July 24, 1796. Unless otherwise cited, all Monroe correspondence is referenced in A Comprehensive Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe, edited by Daniel Preston, 2 vols. (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2001).

In 1803 President Jefferson appointed Monroe to a second tour as minister to France, charging him with the responsibility of negotiating certain aspects of the Louisiana Purchase from France. Being nearly destitute, France was hoping to replenish its treasury after Napoléon’s extensive military campaigns.

David B. Mattern, ed., The Selected Letters of Dolley Payne Madison (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), p. 209.

The two girls long remained loyal to Madame Campan, and Eliza, who eventually married her father’s assistant, George Hay, honored the experience by naming their only daughter Hortense Eugenie Hay, after Napoléon’s stepdaughter Hortense and stepson Eugène Beauharnais.

Maria was an infant when the family set sail for France in 1803. Arriving at Le Havre, she remained with her parents when her sister Eliza returned to studies at Mme Campan’s school at Saint-Germaine. While Mr. Monroe attended to business in Paris and traveled, his wife and daughter stayed with family friends from Virginia, Fulwar Skipwith and his wife, the Virginia-born Flemish countess, Evelina Louisa Barlie Van de Clooster. The Skipwiths, like the Monroes, were known for their discriminating style. See Henry Bartholomew Cox, A Parisian American: Fulwar Skipwith of Virginia (Washington, D.C.: Mount Vernon Publishing Co., 1964).

He constructed the press for William Goddard, publisher of the Pennsylvania Chronicle. See Priscilla Searles, “An Empire of the Mind,” Business New Haven, September 15, 2003, www.conntact.com/archive_index/archive_pages/4481_Business_New_Haven.html (Connecticut Business News Journal; accessed January 29, 2008).

Isaac Doolittle’s mother, Desire Bellamy (1758–1833), hailed from an educated Connecticut family. Her brother, the Reverend Dr. Bellamy, was a distinguished Congregational minister and graduate of Yale.

One “Israel” Doolittle is noted having served as a courier of official correspondence between Washington and the Parisian consulate. I[saac]. Doolittle in Washington, D.C., to James Monroe in Washington, D.C., October 13, 1813. The editor of the Monroe papers has misinterpreted the “I. Doolittle” signature on the letters to be that of Isaac Doolittle’s much older cousin Israel. See Preston, Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe, p. 365.

Isaac Doolittle in New Haven, Connecticut, to Secretary of State James Monroe in Washington, D.C., September 9, 1814, National Archives Microfilm Publication (NAMP) T1, roll 5, Dispatches from Consuls, 1790–1906, Record Group (RG) 59; National Archives (NA), Washington, D.C.

Benjamin Silliman, ed., “Notice of the Lithographic Art,” American Journal of Science and Arts 4 (1821): 169.

Ibid.

Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to James Monroe in Washington, D.C., April 29, 1822, James Monroe Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to Martin Van Buren in Washington, D.C., May 14, 1831, NAMP T1, roll 6, RG 59, NA. Among the drawings by Poussin in the National Archives are “Plan Projected for a Cooperation of Defense of the Mississippi with Ft. St. Philip,” drawn in 1817; see “Cartographic and Architectural Branch, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers” (88-2 Security file), and “Projected Forts on the Middle Ground and East Bank for the Defence of the Channel at Sandy Hook,” 1820, in the “Cartographic and Architectural Branch, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers” (Forts Dr. 36, Sheet 25). Jean Rodolphe Perronet (1708–1794) served as the founding director of the École des Ponts et Chaussées.

Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to David Warden in Paris, July 18, 1814, NAMP T1, roll 5, RG 59, NA.

For information concerning Benjamin Franklin’s printing press in France, see Ellen R. Cohn, “The Printer of Passy,” in Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World, edited by Page Talbot (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 235–72. See James Monroe in Paris to Fulwar Skipwith in Paris, July 1796, regarding printing and Benjamin Franklin Bache in Philadelphia. Preston, Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe, p. 62.

Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to Albert Gallatin in Paris, July 17, 1816, NAMP T1, roll 5, RG 59, NA.

“Documents in relation to furniture, &c. for the Presidents House,” in House Reports of the Eighteenth Congress, 2d session (Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1818), p. 162. Barnet was finally reimbursed for the looking glasses on January 12, 1818, through a government account with Russell and Lafarge.

M. Christian, Description des machines et procédés..., 15 vols. (1811–1828; Paris: Chez Madame Huzard, 1827), 14: 303–4. Although not published until 1827, the entry for the Honoré patent is dated January 31, 1822, and notes “brevet d’invention de cinq ans”(five-year summary of inventions).

George C. Groce and David H. Wallace, The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564–1860 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957), s.v. “William Armand Barnet.”

Morey had secured approximately twenty patents for internal combustion engines; www.wikipedia.com, s.v. “Samuel Morey” (accessed January 28, 2008).

Isaac Doolittle, “Remarks on the Revolving Steam Engine of Morey,” American Journal of Science and Arts 2 (1820): 101–5. John L. Sullivan, “On the Revolving Engine, in Reply to Mr. Doolittle,” American Journal of Science and Arts 2 (1820): 106–14.

The New York Daily Advertiser, June 13, 1820, notes the arrival of the ship Criterion “40 days from London, and 34 from the Downs,” listing among the passengers “S. Barnet, Mrs. Barnet, and W. Barnet.”

Georgia B. Barnhill, “The Introduction and Early Use of Lithography in the United States” (paper, 67th IFLA Council and General Conference, August 16–25, 2001), p. 3. The New York Evening Post, October 24, 1821, noted in the Marine List that the sloop Orion Godfrey had arrived in three days from Boston with merchandise for various businesses, including the firm of Barnet and Doolittle, further verifying that they were in operation well before the end of the year.

A copy of Children’s Friend, Number III, can be found in in the collection of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.; a copy of The Grammar of Botany can be found in the collection of the New York Public Library. See Barnhill, “Introduction and Early Use of Lithography in the United States,” p. 3.

James R. Schenck, The Directory and Stranger’s Guide, for the City of Charleston . . . for the Year 1822 (Charleston, 1822), s.v. “Barnet.” As “Agent for Claims and for Seamen” he helped to write insurance policies on ships and sailors, one of his duties as consul.

Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to James Monroe in Washington, D.C., April 29, 1822, James Monroe Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Pocket Magazine, 1828, cited in Richard Corson, Fashions in Hair: The First Five Thousand Years (Suffolk, Eng.: St. Edmundsburgh Press, 1995), p. 467.

Papers of John C. Calhoun, edited by W. Edwin Hemphill, 28 vols. (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1972), vol. 6, 1821–22, p. 400. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun heard of the loss and wrote the president on September 28, 1821, to express his condolences: “We sympathize most sincerely in the loss of your grand daughter. The shock must have been severely felt by Mr. & Mrs. [Samuel L.] Gou[verneu]r.”

The Writings of James Monroe, edited by Stanislaus Murray Hamilton, 7 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902), vol. 6, 1817–23, p. 296. James Monroe to James Madison on May 25, 1822: “Mrs. Gouverneur has added a son to our family, & both mother and child are doing well.”

William Armand Barnet in Paris to Benjamin Silliman in New Haven, January 12, 1828, Silliman Papers, Yale University Library. Yale mistakenly attributes the letter to Isaac Cox Barnet, but the last page is clearly signed “WA Barnet.”

M. P. S. Girard, “Memoir on Navigable Canals” (translated by I. Doolittle), American Journal of Science and Arts 4 (1822): 102.

Amos Doolittle’s engraving of Dr. Elisha Mitchell’s map “Geology of the Gold Region of North Carolina” appeared in Silliman’s American Journal of Science and Arts 11 (1829). Mitchell, a Yale graduate, had been a student of Silliman. In correspondence with Secretary of State Martin Van Buren dated April 28, 1831, Barnet continued to promote lithography, enclosing a book with lithographic illustrations of bridges and causeways as a gift for President Andrew Jackson. The diplomat believed the illustrations could be useful for developing a system of roads and navigable waterways in America and put forth his hope that “the Collection will be found acceptable to the President.” Isaac Cox Barnet in Paris to Martin Van Buren in Washington, D.C., April 28, 1831, NAMP T1, roll 6, RG 59, NA.

The announcement of Bass Otis’s first American lithograph, Minerva, appeared in the premier issue of Benjamin Silliman’s American Journal of Science and Arts 1 (1819). For further information on Otis’s experiments, see Philip J. Weimerskirch, “Naturalists and the Beginnings of Lithography in America,” in From Linnaeus to Darwin: Commentaries in the History of Biology and Geology (London: Society for the History of Natural History, 1985), p. 169; and Sally Pierce, Catharina Slautterbach, and Georgia Brady Barnhill, Early American Lithography: Images to 1830 (Boston: Boston Athenaeum, 1997). No copy of Otis’s Minerva is known to survive.