View of Shepherd Mountain looking northwest from Interstate 64, just west of its intersection with the Uwharie River. The peak is 1,150 feet above sea level. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.)

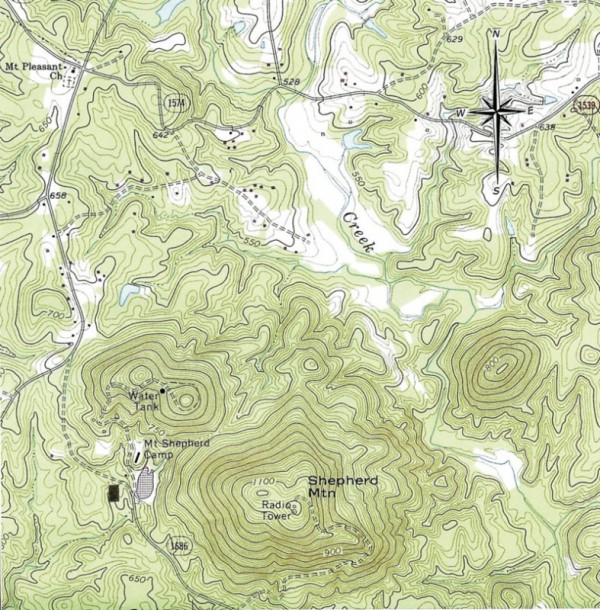

Detail of U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle of Glenola, North Carolina, 1981, showing the topographic setting of the Mount Shepherd pottery site and the network of roads to the north, several likely dating to the colonial period. The site, marked by a black rectangle, measures 200' x 200'; the contour interval is 10'.

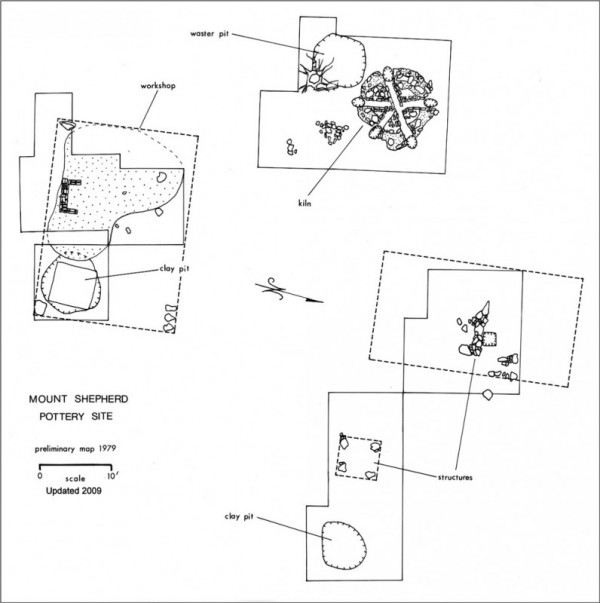

Drawing showing conjectured structure outlines. (All site drawings by Alain C. Outlaw.) This drawing is an updated version of the one submitted in 1979 with the National Register of Historic Places nomination form.

Native American pottery sherds, North Carolina piedmont, 500–1000. Low-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.) Only seven prehistoric ceramics sherds were found during excavations, indicating that Native Americans did not occupy the site during the Woodland period.

Jug fragments, Germany, 1750–1770. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The decorative checkerboard design on this vessel may have been a design source for the fragmentary dish illustrated in fig. 46.

Saucer (left) and teabowl (right) fragments, England, post-1770. Creamware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The presence of this ware type helped to date the site to post-1770.

View of the kiln at the Mount Shepherd site prior to excavation. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) This feature was covered by a circular mound of rocks. J. H. Kelly and A. R. Mountford excavated the backfilled trench on the left in 1971.

Post-excavation view of the kiln. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) A waster pit is visible in the upper left corner of the excavated area.

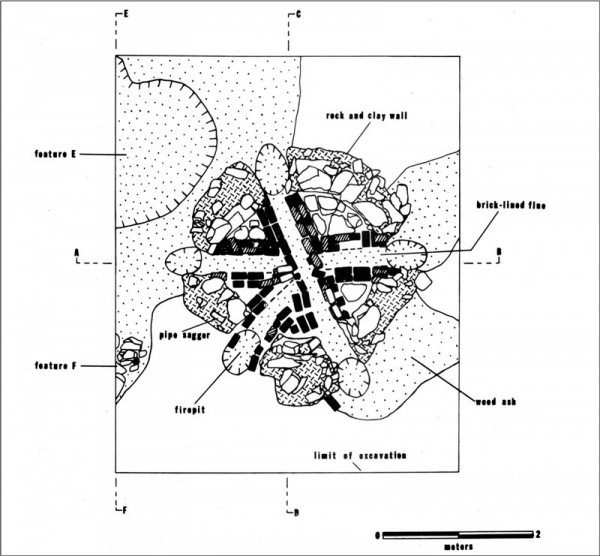

Drawing of the floor plan of the Mount Shepherd kiln.

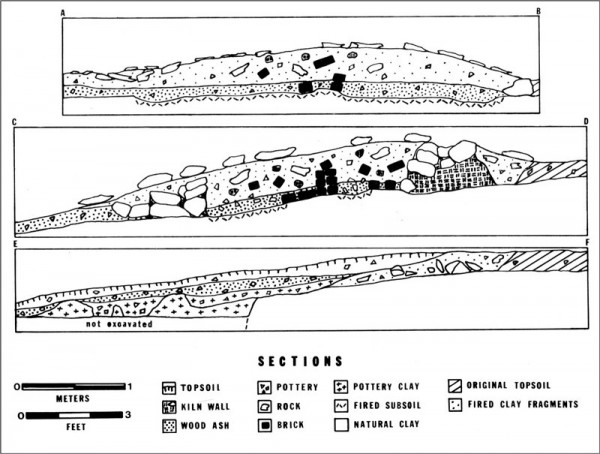

Sectional drawing of the Mount Shepherd kiln.

Drawing of a pottery kiln (left) and pipe kiln (right) by Reinhold Rücker Angerstein, probably England, 1753–1755. (R. R. Angerstein’s Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753–1755: Industry in England and Wales from a Swedish Perspective, trans. Torsten Berg and Peter Berg [London: Science Museum, 2001], pp. 204, 311.) According to Angerstein, the pottery kiln was near Prescott, England. The pipe kiln was near Liverpool and had “six little fireplaces.”

Trivets, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Kiln props and spacers, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Saggers, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar fragments from the last firing lie in a brick-lined flue inside the kiln. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) The center of the kiln is at top center.

Crocks, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of crock at right 7 1/8". (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Crock rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Crocks and chamber pot, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

View of the excavated workshop area at the Mount Shepherd site. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.)

Reassembled marlys from five dishes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Bowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

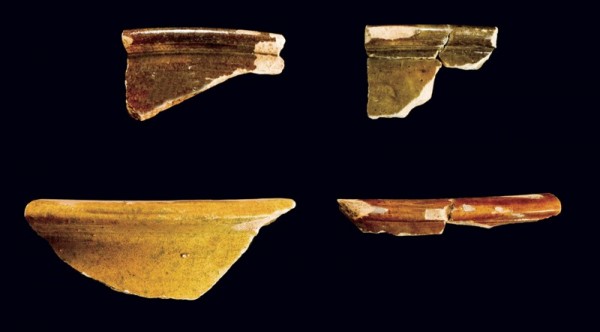

Bowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Bowl fragment, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1770. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Cream jar rims, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar base fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The illustrated marks are VI, VIII, and X.

Partially reassembled dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish rim fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) Salem dishes with similar backs and rims are illustrated in “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina” by Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown in this volume.

Partially reassembled dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Partially reassembled marly from a dish, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Partially reassembled marlys from two dishes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

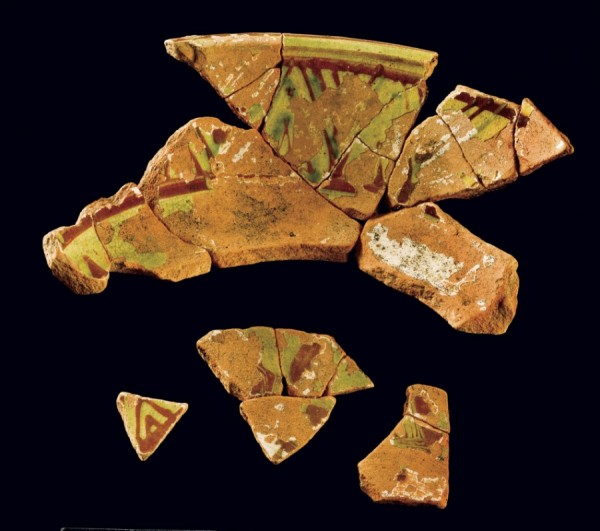

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The decoration on the cavetto fragments is closely related to that on sherds recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site in Bethabara (see in this volume Beckerdite and Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina,” fig. 69).

Dish fragment, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This glazed marly fragment shows how Meyer’s scrolling-vine-and-leaf motif would have looked after firing (see fig. 32).

Detail of the marly of a fragmentary plate, recovered at Lot 49, Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish fragment, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

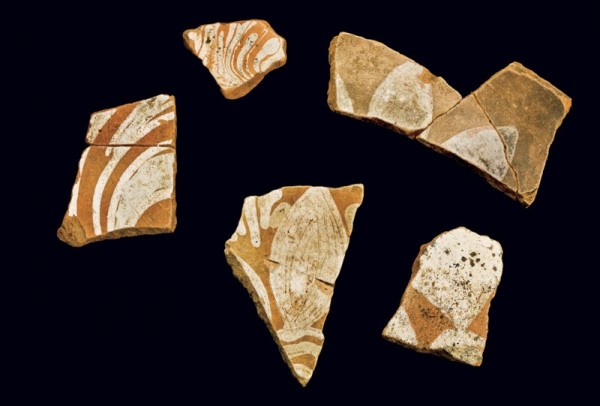

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) The leaves are strikingly similar to those on fragments recovered at Salem and on several of the intact examples of Wachovia slipware illustrated in this volume in Beckerdite and Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina,” figs. 32, 35.

Dish, Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

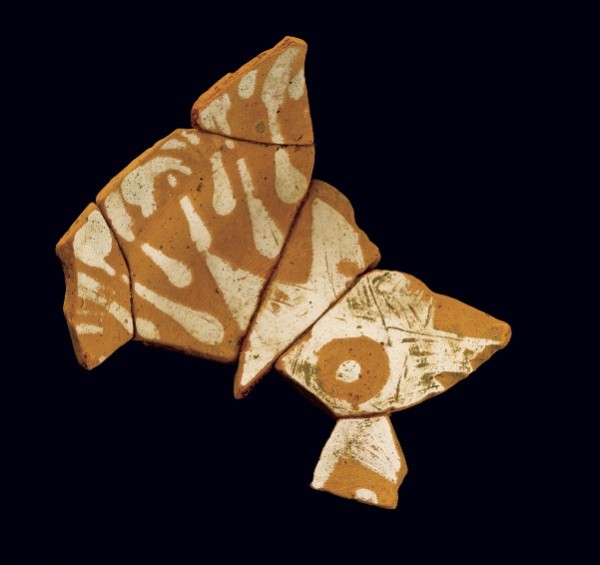

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) Marks left by the decorator’s trailer are visible on the broad leaf on the triangular sherd in the center.

Detail of a dish probably made during Rudolph Christ’s tenure as master of the pottery at Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) Marks left by the tip of the decorator’s trailer are visible on the tulip-shaped flower.

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Interior view of the porringer illustrated in fig. 49.

Porringer, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Porringer, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Porringer fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Porringer, recovered at Gottfried Aust’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1756–1771. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

Jug or bottle mouths, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Jug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Jug fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Base fragments from mugs, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Base fragments from mugs, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Mug rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Mug, probably Salem, North Carolina, 1780–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Fragmentary teabowl, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center; photo, John Bivins.) The current location of this fragment is not known.

Teabowl fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) These sherds and those illustrated in fig. 63 could be from the same teabowl.

Teabowls, recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1789–1802. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.) The white-slip coatings of these bowls suggest that they were intended to have green or tortoiseshell glazes.

Milk pan fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Handle fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Lid fragment and rim fragment, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Jar fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Tile stove, Salem, North Carolina, 1775–1830. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens; photo, Wesley Stewart.)

Photograph of a pottery workroom, Salem, North Carolina, 1905. (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The stove was used at the Schaffner-Krause pottery in Salem.

Stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

View of the back of the stove tile illustrated in fig. 72.

Detail of the back of the stove tile illustrated in fig. 72.

Fragmentary stove tile, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Pipe bowl, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Pipe bowl (front view), Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Side view of the pipe bowl illustrated in fig. 78.

Bottom view of the pipe bowl illustrated in figs. 78 and 79, showing the tripartite motif.

Sagger fragment with pins and pipes, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Dish fragments, Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.)

Sugar bowl, possibly Mount Shepherd pottery, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

Located in central North Carolina, eight miles west of Asheboro, the site of the Mount Shepherd pottery was discovered in 1969 by two boys who lived nearby.[1] Subsequently identified that year as a pottery manufactory by curators from Old Salem, the site was first archaeologically tested in 1971 by James H. Kelly and A. R. Mountford, both from the Stoke-on-Trent Museum in Staffordshire, England.[2] In 1974 I excavated the kiln with volunteers under the sponsorship of the Seagrove Pottery Museum and, in 1975, investigated other features with the assistance of St. Andrews Presbyterian College, Louisburg, North Carolina.[3] The “Mount Shepherd Pottery Site” was entered on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[4] A small grant in 2007 from the North Carolina Archaeological Society in Raleigh allowed the consolidation and curation of the artifact collection housed at the United Methodist Church camp at Mount Shepherd and led to new studies of the material sponsored by the Wheatland Foundation, Inc., Williamsburg, Virginia, and the Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The Site

The potter who occupied the Mount Shepherd site probably chose it for reasons of economic accessibility, visibility, and availability of raw materials. The land lies along the trading path linking Pennsylvania to the Carolinas, near intersections with other colonial roads leading to potential markets in all directions (figs. 1, 2).[5] Shepherd Mountain rises to an altitude of 500 feet over the relatively short distance of 3,000 feet from the pottery site to the peak. A visual marker for travelers following the trading path and adjoining roads, the mountain was an ideal location for a manufactory. In a rural setting of open pasture and wooded lands looking today much as it did in the eighteenth century, the site provided abundant raw materials essential for a pottery works.

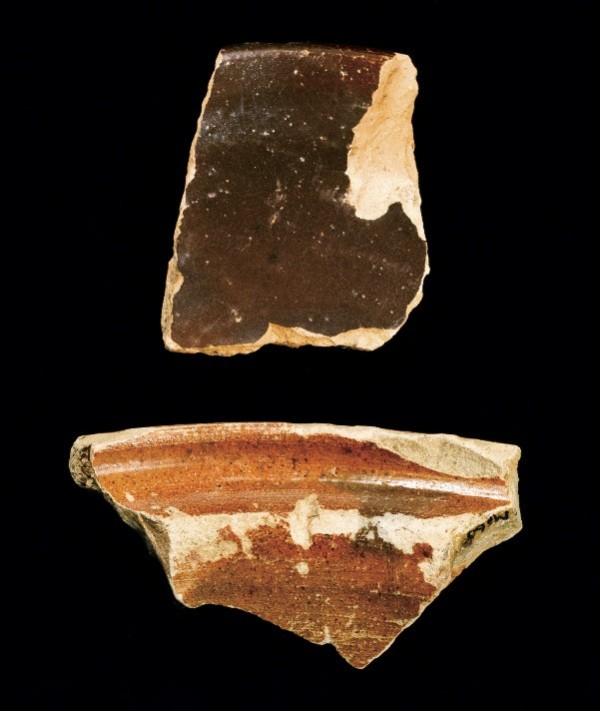

Situated on a narrow wooded ridge at the base of Shepherd Mountain, the site’s components were obvious because of visible mounds and depressions. Excavations in 1974 and 1975 uncovered the remains of a kiln, a workshop, a residence, and other structural features dating to the late eighteenth century (fig. 3). In addition, archaeologists discovered intense prehistoric use as early as 7000 B.C. Finished stone tools and related fragments were found in the thin topsoil overlying the site, indicating that abundant stone resources drew Native Americans to this location for the manufacture of projectile points and scrapers in the Archaic period (8000–1000 B.C.). In contrast, only a handful of decorative Native American pottery sherds from the Late Woodland period (A.D. 800–1650) were found, suggesting that the Mount Shepherd potter collected them as examples of Native ware decoration (fig. 4).[6]

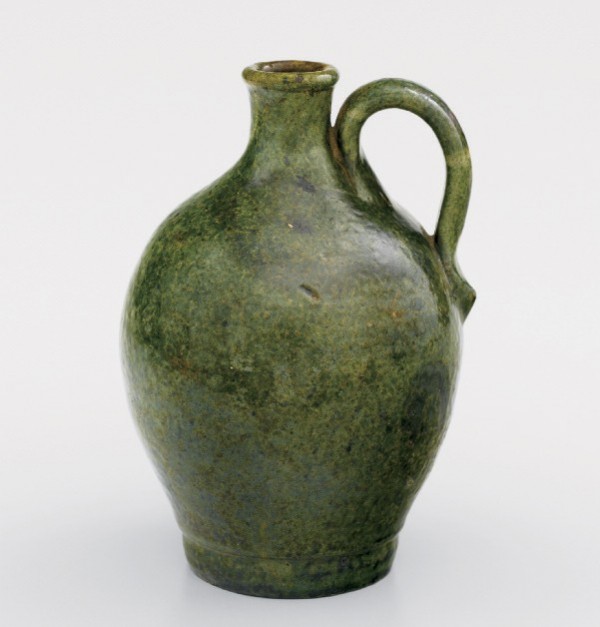

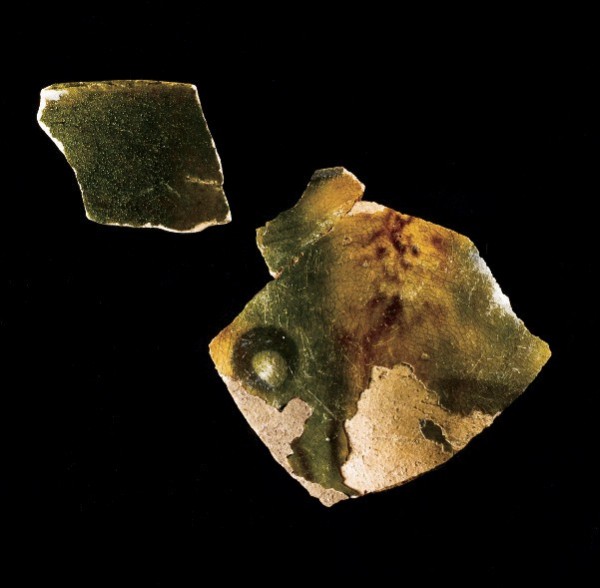

The sheer volume of sherds from pottery excavations can be daunting, and the Mount Shepherd site proved to be no exception. The area was heavily laden with earthenware sherds and in fact contained more pottery than dirt. Helping to date the occupation to the late eighteenth century were the few European ceramic vessels recovered, including a Rhenish stoneware jug and an English creamware teabowl and saucer (figs. 5, 6). Further pointing to the late 1700s were a small number of copper objects, including a post-1760 George III halfpenny, a 1773 Virginia halfpenny, a cuff link inscribed “tally-ho,” a button, and a brass upholstery nail with a forged shank.

Documentary Research

Production dating to the last decade of the eighteenth century was determined in 1980, when L. McKay Whatley of Asheboro identified the Mount Shepherd potter by assembling land plats with common borders. In 1793 Jacob Meyer received a grant from the State of North Carolina for a 100-acre tract near the center of Mount Shepherd, which included the site of the pottery. Eight additional documents confirmed Meyer’s presence in Randolph County between October 1793 and November 1, 1799, although he died in Bethabara, North Carolina, on September 22, 1801.[7] Established in 1753, Bethabara was the first settlement of Wachovia, a 100,000-acre tract about fifty miles northwest of Shepherd Mountain.

Philip Jacob Meyer, also called Jacob Meyer Jr., was born in Bethabara on October 25, 1771. Three months after his birth, Meyer’s father, Jacob Sr., was transferred to Salem to manage the new tavern. Jacob Jr. began work in the pottery trade in January 1786, when he was apprenticed to master potter Gottfried Aust in Salem.[8] A short time later, Meyer appeared in the Moravian records for his “bad pranks” and for making a “very bad utterance.”[9] Not one of Aust’s most diligent apprentices, he overheated the kiln in December 1788, causing “most of the pottery” to turn out “crooked.”[10] Because of his “bad way of life,” church leaders expelled him from Salem in June 1789. Over the next six months, he went to New Bern, North Carolina, returned to visit Salem and Bethabara, and then traveled to Pennsylvania and Virginia. In November 1789 Meyer returned to Bethabara once again, this time to live with his brother-in-law Gottlob Krause, who was master of the pottery there and a former Aust apprentice. Meyer might have worked for Krause, although there is no documentation in the Moravian records. Meyer married Susannah Helsabek in Bethabara on March 27, 1791, where his only child was born the following January.[11]

The Excavations

The 1974 excavations focused on the remains of a circular kiln, characterized by a low mound of rock along the west edge of the site (fig. 7). This feature was stratigraphically excavated in quadrants for the recovery of artifacts in different sections of the kiln. The kiln had five flues with five matching fire pits at their entrances and a downhill wall with dimensions indicating that the overall original structure was ten feet in diameter on the exterior, six feet in diameter on the interior, and two feet thick (figs. 8-10). Although the flues were lined with brick, the kiln was constructed of stone bonded with clay on a roughly circular foundation. This footprint, the debris, and circa 1753–1755 drawings of an English pottery kiln and pipe kiln (fig. 11) provided evidence for the appearance of the Mount Shepherd kiln.[12] Presumably Meyer based his design on the kilns at the Salem pottery.[13] The kiln furniture used by Meyer also matches that recovered at Wachovia sites. Among the artifacts found are trivets with pinched legs, short-footed props, a formed wad of clay with a cavity, straight-sided saggers, and rolled clay pegs that supported pipe bowls placed in the saggers (figs. 12-14).

The removal of loose rocks covering the kiln revealed sherds of numerous crocks in the flues, documenting the presence of that form in the kiln during the last firing (fig. 15). Reconstructed examples (fig. 16) show that the tallest jar was just over seven inches in height, and that all were slightly convex except for one slightly rounded example (fig. 17). The rim and body shape of Meyer’s standard crock form mirrors that of Wachovia examples (fig. 18). As was the case with most Germanic utilitarian earthenware, forms changed little over time, and this was also true of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century pottery in the North Carolina Moravian tradition.

The remaining visible mounds and pits were excavated in 1975. South of the kiln, building stone alignments and a reddish orange clay delineated a workshop measuring twenty feet square. Archaeology also showed that a depression with a residual bottom layer of gray pottery clay inside that perimeter was a six-foot-square clay pit, which extended two feet deep, and that a three-sided, handmade brick foundation measuring four feet by two feet was the remains of a clay stove embedded in the reddish orange clay floor (fig. 19). Excavations of a mound along the crest of the hill and a short distance northeast of the kiln revealed a residence with stone footings and central chimney, estimated to be sixteen by thirty-two feet. Its east wall was parallel to and in line with the workshop. East of the residence are stone piers to support a structure six feet square, and an irregular pit six feet on one side.

The last feature excavated at the site was a waste-filled pit off the southwestern corner of the kiln. Its location suggests it was dug to obtain clay for construction of the kiln. As a large, deep, and potentially hazardous disturbance in the working floor of the pottery, it was likely the receptacle for an early—perhaps even the first—unsuccessful firing. The pit contained underfired vessels with a clay body the consistency of powdery chalk, and vessels whose walls were too heavy for their bases, making them structurally unsound. This waster material suggests that Meyer fired storage vessels, dishes, plates, milk pans, and chamber pots together. Among the remains were at least twenty-five slip-decorated dishes and plates ranging from about 10 1/2 inches to just over 13 inches in diameter (fig. 20).[14]

The Pottery

Analysis of the total ceramic assemblage revealed that most of Meyer’s vessels were wheel-thrown earthenware made of local clay and fired with either clear, brown, green, or black lead glaze. As appears to have been the case with Wachovia ware, nearly all of the slip-trailed forms produced at Mount Shepherd are flatware—dishes, plates, and shallow bowls (fig. 20). The only exceptions are steep-sided bowls with swirled slip decoration. As the sherds illustrated in figures 21 and 22 indicate, Meyer’s bowls were similar to those produced by Aust at Bethabara (fig. 23). All of the decorated wares produced at Mount Shepherd and Wachovia were bisque-fired to harden the body and bond the slip (fig. 21), then burned a second time to glaze the ware (fig. 22). Once fired, the slips appeared yellow, reddish brown, and/or brown, depending on whether the potter added metallic oxides. In both form and decoration, the pottery produced at the Mount Shepherd site mirrored that made earlier and contemporaneously at Salem. Because the site of the Salem pottery has yet to be investigated, the slip-decorated fragments associated with Meyer provide the best archaeological index of motifs used by early Moravian potters in North Carolina.

Cream jars were the most common ceramic form recovered at the Mount Shepherd site. A few jars are glazed on the exterior (fig. 24), but most are glazed only on the interior. Measuring about 4 1/2 inches in diameter, some of the bases are inscribed with Roman numerals (fig. 25). Aust and the potters he trained utilized at least two marking systems. Scholars have speculated that Aust used Roman numerals during his tenure as master at Salem and Bethabara and Rudolph Christ used Arabic letters, though the meaning and authorship of the marks remain uncertain. Some of the marks, such as the Roman numerals on the Mount Shepherd crock bases, appear to be price marks; others may denote piecework.[15]

A large percentage of the sherds associated with Meyer are from slip-trailed dishes (figs. 20, 26). The profiles and rolled and undercut rims of his dishes, plates, and bowls differ little from those on comparable forms known to be by or attributed to Aust and his other apprentices (fig. 27). The marlys of Meyer’s dishes are decorated with a wide range of motifs, including concentric lines (fig. 28), wavy lines (fig. 29), chevrons (fig. 30), imbricated triangles (fig. 31), scrolling vines with broad leaves (fig. 32), and wispy, stylized leaves (fig. 33). Nearly all of these designs occur on Salem slipware (figs. 34, 35). The stylized leaves on the marly sherds at the top of figure 33 are remarkably similar to those on dishes and plates recovered at the site of Gottlob Krause’s pottery in Bethabara (fig. 36), supporting the theory that Meyer worked for Krause before moving to Randolph County.

Although Meyer used a variety of slipware motifs on the cavetti of his dishes and plates, the overwhelming majority was floral. Compositionally, Meyer’s work is virtually identical to that of his Wachovia counterparts. His plant designs rise from a point at the edge of the cavetto and branch out in a naturalistic manner (see fig. 26). The lobate form of Meyer’s leaves (figs. 37, 38) and the techniques used to outline and infill them have clear precedent in Salem slipware (fig. 39).

Many of the decorated sherds recovered at the Mount Shepherd site have fine, incised lines created by the tip of the potter’s trailer dragging through the wet slip. These are most visible on the interior of leaves and flower petals, where the decorator made parallel strokes to distribute and spread his slip evenly (fig. 40). Similar marks are visible on slipware excavated at Bethabara and Salem, as well as intact dishes and plates documented and attributed to Wachovia potters (fig. 41).

Nearly all of the flowers on Meyer’s slipware can be found on Salem dishes and plates dating from the early 1770s into the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Most common are those representing tulips (figs. 26, 42) and anemones (fig. 43). As Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown suggest in their article “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina” in this volume, anemones held special significance for Moravians. Although there is no exact Wachovia parallel to the star-shaped motif on the sherd illustrated in figure 44, its placement where the cavetto begins to rise and the circular device in the center suggest that it also represents a flower. Further archaeology at Wachovia sites will most likely reveal precedents. Only a few motifs used by Meyer seem to have been inspired by non-Moravian sources. The checkerboard pattern on the dish fragments illustrated in figures 45 and 46 probably was inspired by Rhenish stoneware owned by Meyer (see fig. 5). All of these sherds appear to have come from a single dish.

The hollow ware forms excavated at the Mount Shepherd site are also similar to those made by Wachovia potters during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Meyer’s porringers had slightly ovoid bodies with flaring lips and feet, incised lines on the shoulder, and pulled handles (figs. 47-50). Identical details appear on two examples likely made at Salem, one with a tortoiseshell glaze (fig. 51), the other with a lustrous black lead glaze (fig. 52). One porringer from Meyer’s site was made of white pipe clay with copper-green glaze on the interior and clear lead glaze on the exterior (fig. 53). All of these are of essentially the same form as the porringers Aust made in Bethabara during the 1750s and 1760s (fig. 54).[16]

Beverage containers produced at Meyer’s site include bottles, jugs, and pitchers. The jug mouths illustrated in figure 55 indicate that he produced that form in a variety of sizes and glaze colors, as did Meyer’s Wachovia counterparts (figs. 56, 57). The bisque-fired sherd on the left in figure 55, which is coated in white slip, was almost certainly intended for a copper green glaze. The shapes of these necks and mouths also conform to those on jugs made in Bethabara and Salem. The Salem examples typically have pulled handles with a thumb impression or angular “tail” at the lower terminal. One jug fragment recovered at the Mount Shepherd site has a deep thumb impression and vertical green glaze drips (fig. 58). As the porringer illustrated in figure 52 suggests, the use of subtle glaze accents was part of the Wachovia tradition. There is no evidence that Meyer decorated his hollow ware with slip-trailed motifs like those he used on dishes. The same is true of the potters working in Bethabara and Salem.

Most of the drinking vessel fragments recovered at the Mount Shepherd site are from small mugs with brown and black glazes applied directly on the clay body, or green and tortoiseshell glazes applied on white slip (figs. 59, 60). One rim fragment has a green glaze applied directly on a pipe clay body, which obviated the need for white slip (fig. 61). The shape of these mugs resembles that of contemporary Wachovia examples, which have rib-generated moldings and slightly flared rims and bases (fig. 62) Much of Meyer’s tableware appears to have been glazed in tortoiseshell colors, like the teabowl sherds shown in figures 63 and 64. The shape of his teabowls was essentially the same as those made by Aust and his apprentices (fig. 65).

Meyer began his apprenticeship in Salem in 1786, the year Aust and Rudolph Christ entered into a contractual agreement limiting Aust’s production to pottery made from “non-washed clay [utilitarian earthenware and slip-decorated ware]” and Christ’s to pottery made from “washed clay, which may be glazed with all sorts of colors [imitation creamware].”[17] The types of products recovered from the Mount Shepherd site suggest that Meyer worked for both Aust and Christ during his apprenticeship, a theory supported by Meyer’s occasional use of pipe clay for thrown ware. William Ellis, a journeyman from John Bartlam’s pottery in Charleston, South Carolina, probably initiated that practice when he visited Salem in 1774 and shared his knowledge with Aust about the manufacture of creamware.[18] Although it is uncertain whether Aust and Christ ever mass-produced such wares, they clearly succeeded in making variants and experimented with the use of kaolin in both Bethabara and Salem.

Given their prevalence on Wachovia sites, it is surprising that excavation of Meyer’s pottery yielded only a few milk pan sherds (fig. 66) and three handle fragments (two of which are illustrated in figure 67), which appear to be from basins, large bowls, or chamber pots. Unique finds included a flat lid and a hollow ware rim with an interior shelf to accommodate a lid (fig. 68). Several other jar fragments made with the refined pipe clay body were also recovered (fig. 69).

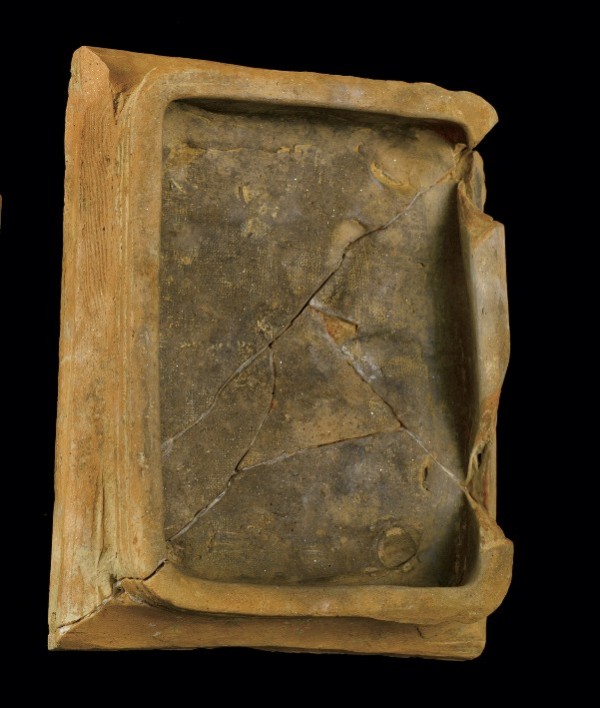

Like Aust and his successors at the Wachovia potteries, Meyer made press-molded stove tiles and smoking pipes. Ceramic stoves, which were more efficient for heating than open fires, were used in Moravian households in both Pennsylvania and North Carolina (fig. 70).[19] A 1905 photograph of a “potter’s room” in Salem shows a tile stove resting on a brick foundation (fig. 71).[20] This example differed from those used domestically, but it may have resembled the stove that originally sat in Meyer’s workshop. Most of the tiles recovered at his site were found in that general context.

Meyer made his stove tiles in two parts: a press-molded face with relief decoration (figs. 72, 73); and a hand-modeled, rectangular support on the back (figs. 74, 75). Two sets of tiles had equestrian figures in the center and small floral ornaments in the corner. One set has ogee-molded edges (see fig. 72), whereas the other has gadrooning around the perimeter (fig. 76). The subjects of these tiles and the example shown in figure 73 might have been inspired by the infantry and cavalry of General Nathaniel Greene and Lord Cornwallis, who were in the piedmont region of North Carolina in 1781.[21]

Also recovered at the Mount Shepherd site were large quantities of press-molded pipes made of white clay. With one exception (fig. 77), all are in the form of an Indian wearing a fluted headdress decorated with a feathery leaf motif in front (figs. 78-80).[22] This design, which resembles that of pipes from other pottery sites, might have been inspired by depictions of Native Americans, symbolizing America, on map cartouches.[23] Incorporating an image of an Native American might also have been a marketing ploy. Gottfried Aust, who made similar pipes, sold examples to the Cherokee in 1756.[24] Aust and Meyer fired their pipes in straight-sided saggers with holes that supported clay pins to hold individual pipes (fig. 81). Most of the pipes recovered at Meyer’s site were bisque-fired, but some were glazed in tortoiseshell colors.[25]

The excavation of the Mount Shepherd site represents the most comprehensive documentation of a late-eighteenth-century earthenware pottery in the piedmont region of North Carolina. The pottery recovered there offers insights into Jacob Meyer’s work and provides clear evidence of his training with Gottfried Aust, Gottlob Krause, and other Wachovia potters. As was the case at the Salem pottery where he trained, Meyer’s manufactory produced a wide range of utilitarian ware; dishes, plates, and shallow bowls decorated with Germanic slip trailing (fig. 82); and refined table- and teaware in the English taste. Although no intact objects can be attributed to his pottery with certainty, a very unusual covered sugar bowl survives as a likely candidate (fig. 83). The bowl, decorated with manganese and copper to simulate a tortoiseshell glaze, is similar in coloration to many of the examples excavated at Mount Shepherd. As of this writing, a study of the elemental analysis of clay bodies from Mount Shepherd and the Wachovia and Alamance County potters is pending but may help definitively identify other vessels. It is hoped that the illustration of the excavated products in this article will lead to the identification of intact specimens from the Mount Shepherd kiln.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For assistance with this article, the author thanks the late Dorothy and Walter S. Auman, Mary B. Clemons, Stephen Compton, Ronald W. Eads, Melissa M. Money, Merry A. Outlaw, and L. McKay Whatley.

James Wicker, “Archaeologists Explore Old Pottery Site in Randolph,” The Randolph Guide (North Carolina), April 23, 1969, p. 1. The two boys were Jeffery and Lee Farlow.

J. H. Kelly, “Report on the Mount Shepherd Pottery Site, Randolph County, North Carolina,” 1971, report on file, Seagrove Pottery Museum, Seagrove, North Carolina.

Alain C. Outlaw, “Preliminary Excavations at the Mount Shepherd Pottery Site,” in The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers 9, edited by Stanley A. South (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1975), pp. 2–12.

Alain C. Outlaw, “Mount Shepherd Pottery Site,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1979, on file, Historic Sites Section, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh, North Carolina.

J. Collett, “A Complete Map of North-Carolina from an Actual Survey,” 1770, North Carolina Department of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Joffre Lanning Coe, “The Formative Cultures of the Carolina Piedmont,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54, pt. 5 (1964): 121.

L. McKay Whatley Jr., “The Mount Shepherd Pottery: Correlating Archaeology and History,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 6, no. 1 (1980): 40, 46. Whatley wrote his Bachelor of Arts thesis on Moravian stove tiles using Mount Shepherd material. See L. McKay Whatley Jr., “Moravian Tile Stoves of the American Colonial Period” (B.A. thesis, Harvard College, Cambridge, Mass., 1977).

John Bivins, The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), p. 63.

Whatley, “Mount Shepherd Pottery,” p. 46.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 63.

Whatley, “Mount Shepherd Pottery,” p. 46. Meyer was living with Susannah Helsabek before they married. The minutes of the Congregation Council for February 3, 1791, noted that “Br. And Sr. Meyer have [been living in] Bethabara for some time . . . and are going to help Br. Gottlob Krause with his household and the education of his children.” Transcribed and filed under Johann Gottlob Krause, Old Salem Research Files, Winston-Salem, N.C.

R. R. Angerstein’s Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753–1755: Industry in England and Wales from a Swedish Perspective, trans. Torsten Berg and Peter Berg (London: Science Museum, 2001), pp. 204, 311.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, pp. 22–23.

Remarkably, an extensive analysis showed that as many as twenty-seven dishes, each twelve inches in diameter, could have been accommodated in a single layer of the six-foot interior of the kiln.

Whatley, “Mount Shepherd Pottery,” p. 46.

The Whieldon-type tortoiseshell glaze had been introduced into the area in 1773, when William Ellis showed Gottfried Aust how to mix this type of glaze. See Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 25.

This dispute and its resolution are discussed in ibid., pp. 33–34.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Escape from Bartlam: The History of William Ellis of Hanley,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 80–102.

Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 181.

Ibid., p. 111.

Hugh F. Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals (1971; repr., Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), pp. 268–318.

In addition, tiny four-lobed designs and a faint raised dot appear in the flutes, at the bowl rims, and at the stem ends.

Margaret Beck Pritchard and Henry G. Taliaferro, Degrees of Latitude: Mapping Colonial America (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2002), pp. 140, 169, 181. See also Alain C. Outlaw, “Backcountry Sophistication: Anthropomorphic Elements from a Piedmont North Carolina Kiln,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 265–68.

Stanley A. South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), p. 238.

Iain Walker summarized this tradition in “The Central European Origins of the Bethabara, North Carolina, Clay Tobacco-Pipe Industry,” in The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe, edited by Peter J. Davey, vol. 4, Europe 1 (Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1980), pp. 11–69.