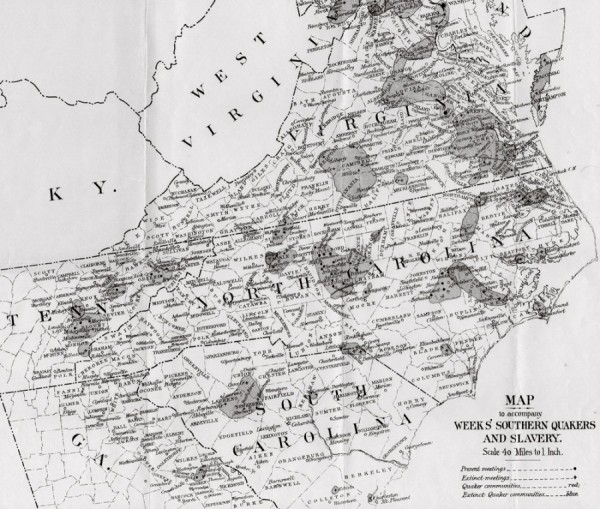

Map showing southern Quaker communities. Reproduced from Stephen B. Weeks, Southern Quakers and Slavery: A Study in Institutional History (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 1896). (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

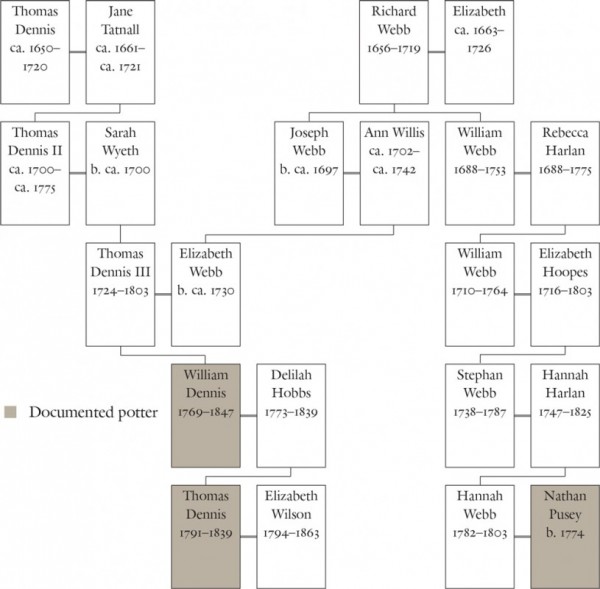

Dennis and Webb family tree. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

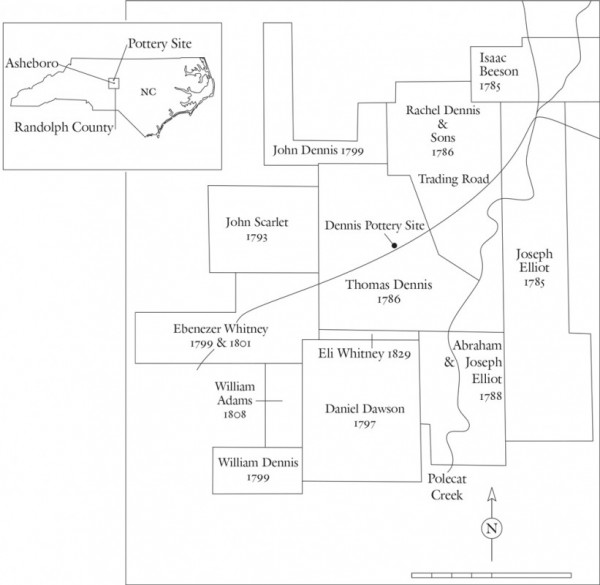

Plat map showing the location of the Dennis Pottery and surrounding landowners. Dates represent the year individuals either applied for or were granted land from the state of North Carolina.

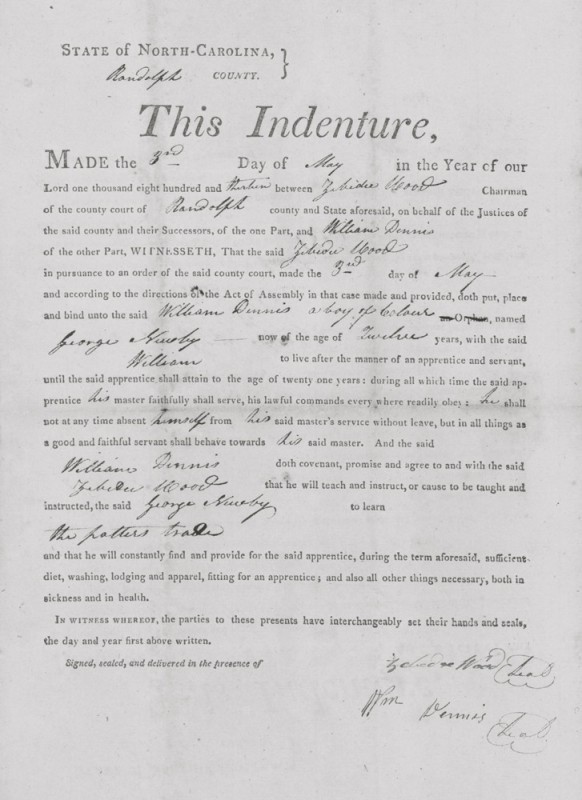

Indenture of George Newby, Randolph County, North Carolina, May 3, 1813. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

William Dennis House, New Salem, North Carolina, ca. 1820. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

Dish fragment recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Kiln tiles recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The tiles on the right are fused together with glaze.

Saggar recovered at the Thomas Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812–1821. H. 7". High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The saggar is representative of the type and size used at both Dennis potteries. On this example, part of the rim has been pinched between the thumb and forefinger to form a decoration, but the vessel was never finished.

Kiln furniture recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.) The ungrooved tile shown at top is vitrified from continual refiring and has adhering saggar and creampot rims from a kiln mishap.

Dish fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Private collection.)

Saggar fragments recovered at the William Dennis pottery site, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. High-fired clay. (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to the William Dennis pottery, New Salem, North Carolina, 1812. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, attributed to the Dennis potteries, New Salem, North Carolina, 1790–1832. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, North Carolina Pottery Center.)

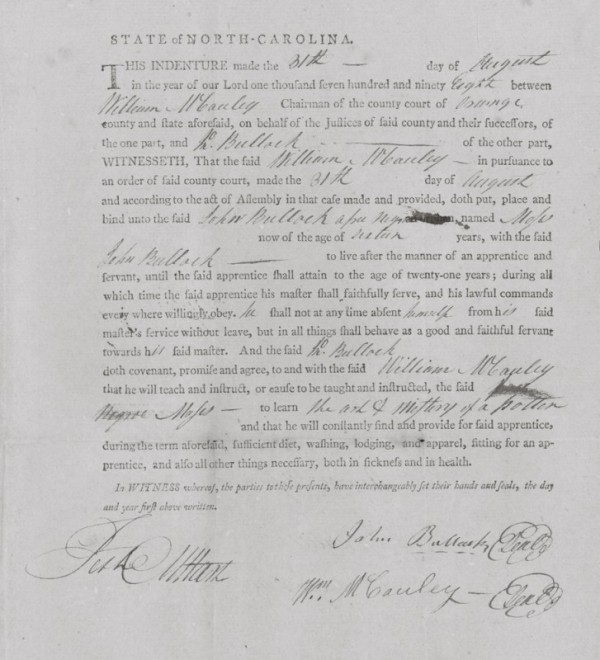

Indenture of Moses Newby, Orange County, North Carolina, August 31, 1798. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

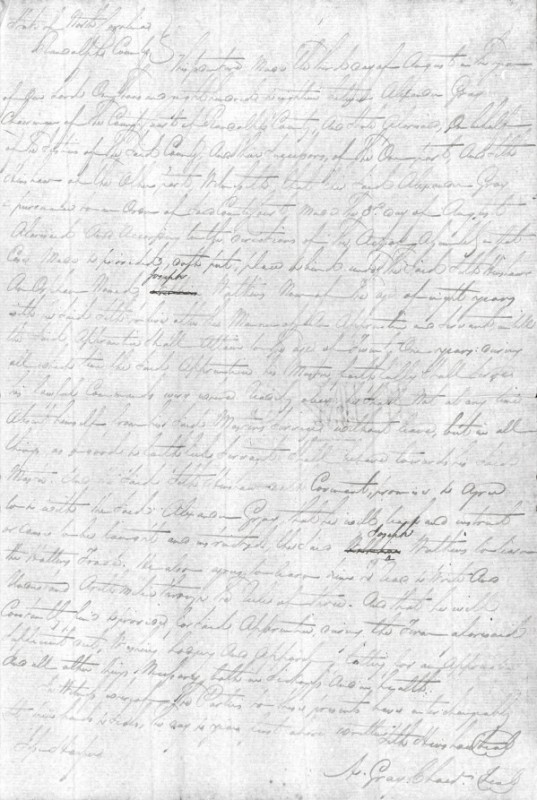

Indenture of Joseph Watkins, Randolph County, North Carolina, August 3, 1818. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

Jar, Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

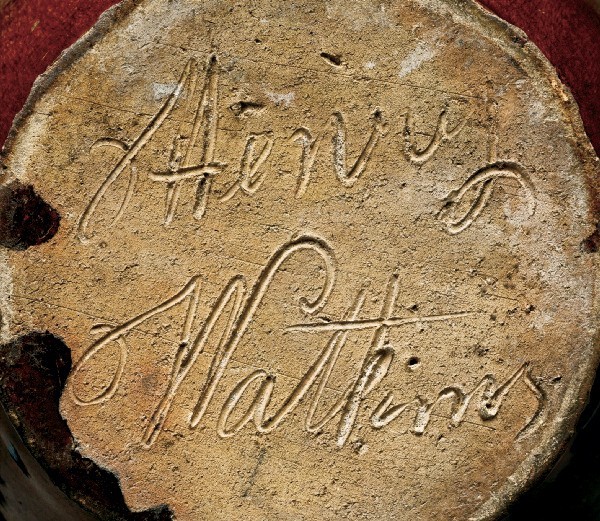

Detail of the incised signature on the bottom of the jar illustrated in fig. 16.

Dish, attributed to Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Fat lamps, attributed to Henry Watkins, Randolph or Guilford County, North Carolina, 1821–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/8" (right). (Private collection [left]; courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens [right].) The example on the right shifted in the kiln and fired upside down.

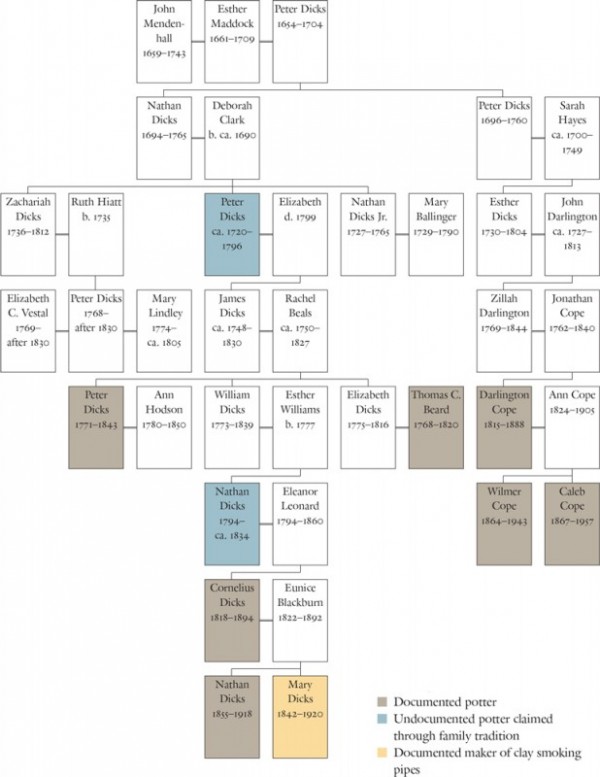

Dicks Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

n Undocumented potter claimed through family tradition

n Documented maker of clay smoking pipes

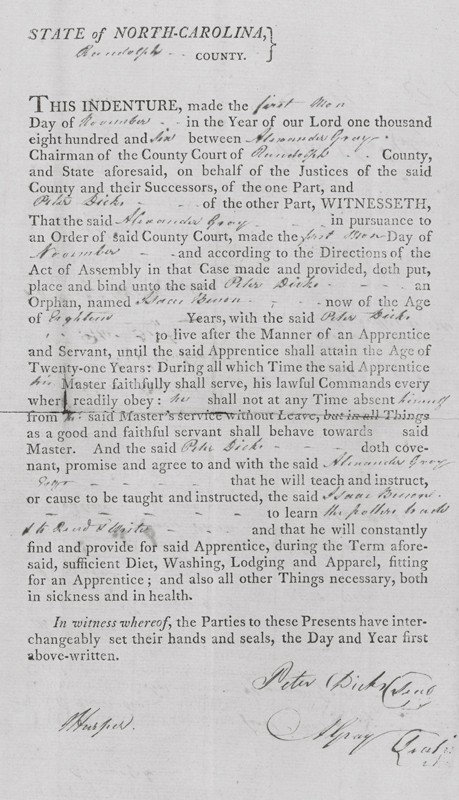

Indenture of Isaac Beeson, Randolph County, North Carolina, November 3, 1806. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.)

Pipe press and molds, Cornelius Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1850–1920. Hardwood (press) and pewter (molds). H. 13 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Hal Pugh.)

Photograph of Mary Elizabeth Dicks Davis (1842–1920). (Courtesy, Ann S. Turner.)

Clay smoking pipes, Mary Elizabeth Dicks Davis, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1900. (Private collection.)

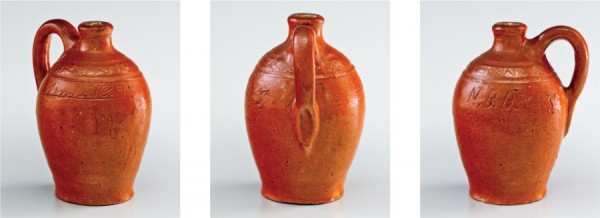

Jug, Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina 1890. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 5 1/2". Inscribed on shoulder: “N. B. DICKS. new market n.c. Jan 12 1890 1 Pt.” (Private collection.) Handles on earthenware associated with Dicks family potters often have an elongated lower terminal.

Skillet, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 5/8" with 5 1/4" handle. (Private collection.)

Pitcher, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/4". (Private collection.)

Jars, attributed to Nathan Dicks, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9 1/2" (right). (Private collection.) These jars exhibit the elongated handle terminal and incised wavy line decoration characteristic of Nathan Dicks.

Fragments recovered at the Nathan Dicks pottery site, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Private collection.)

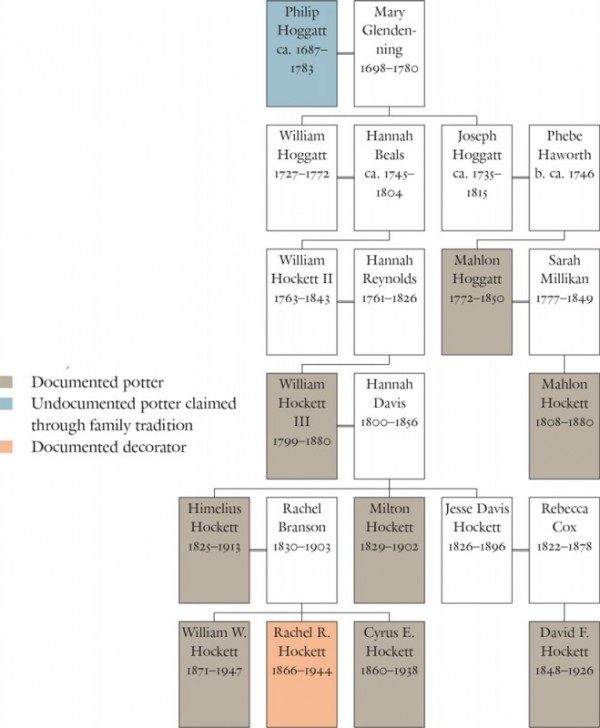

Hoggatt/Hockett Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

n Undocumented potter claimed through family tradition

n Documented decorator

Dish, possibly made by a member of the Hoggatt/Hockett family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1785–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6 1/2". (Private collection.) The rear profile of this dish is similar to that of Moravian examples, but it was removed from the wheel with a twisted cord—a technique not associated with Moravian work.

Photograph of William Hockett III (1799–1880). (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Bottle, attributed to William Hockett III, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1879. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/4". Inscribed on shoulder: “WM RR H 4-19-1879.” (Private collection).

Photograph of Rachel Rodema Hockett (1866–1944), granddaughter of William Hockett III and daughter of Himelius Mendenhall Hockett. (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Photograph of Himelius Mendenhall Hockett (1825–1913). (Courtesy, Jane Coltrane Norwood.)

Chest, attributed to William Hockett III, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, 1828. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3 3/8". (Private collection.) The chest is slab-built.

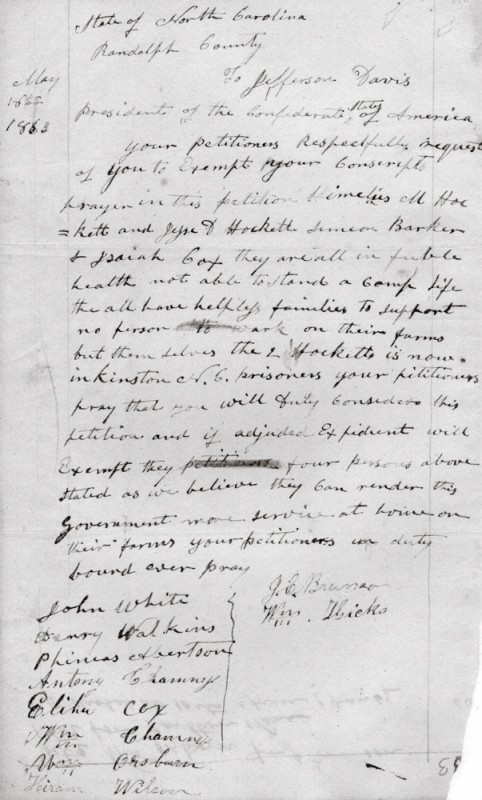

Petition from John Branson to Jefferson Davis, May 18, 1863, requesting the exemption of Himelius Hockett and others. The petition, written on an older account ledger page, was signed by ten neighbors, including potter Henry Watkins. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

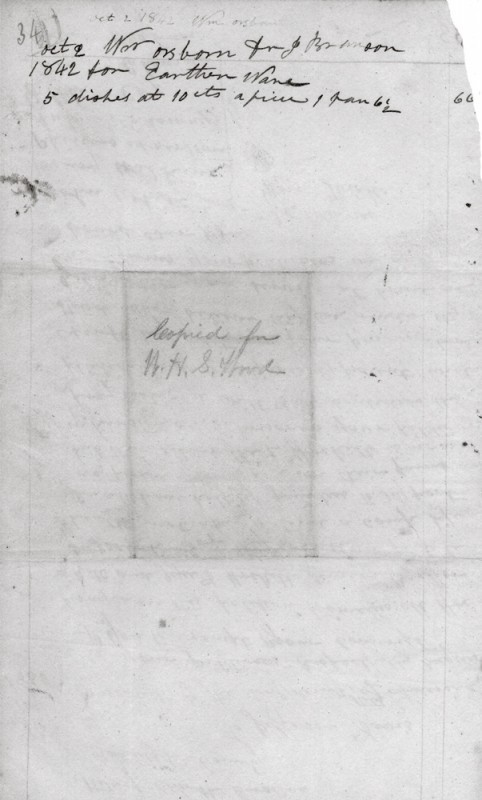

Reverse side of the petition illustrated in fig. 37. On this side, numbered page 34, is recorded an earthenware sale between John Branson and William Osborn: “Oct. 2 1842 Wm Osborn fr J Branson for Earthen Ware 5 dishes at 10 cts a piece 1 pan 6 1/2.”

Colander, attributed to the William Hockett/Hoggatt family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/8". (Private collection.)

Drain tile, David Franklin Hockett, Randolph County, North Carolina, ca. 1875. Unglazed earthenware. L. 6 1/2". (Private collection.)

Exterior view of the David Franklin Hockett kiln, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

Interior view of the David Franklin Hockett kiln showing rock lining, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1875–1910. (Photo, Hal Pugh.)

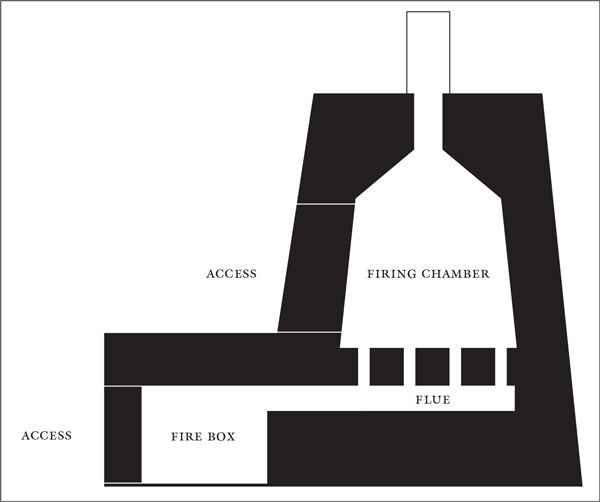

Drawing of the David Franklin Hockett kiln, based on eyewitness accounts.

Overhead view of the partially excavated William Dennis kiln footprint, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1790–1832. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) It is similar in size and shape to the firing chamber of the David Franklin Hockett kiln.

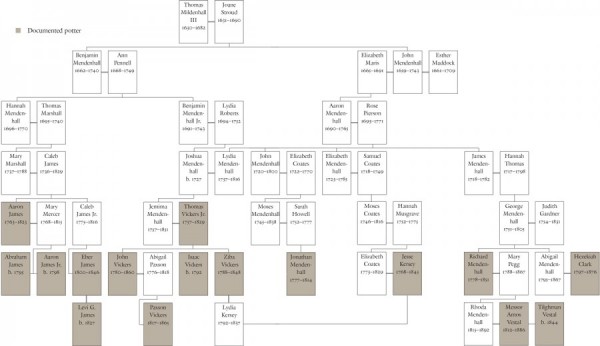

Mendenhall Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

Richard Mendenhall house, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1811. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, Norh Carolina.)

Richard Mendenhall store, Jamestown, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1824. (Courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.) The store was situated across the road from the house illustrated in fig. 46.

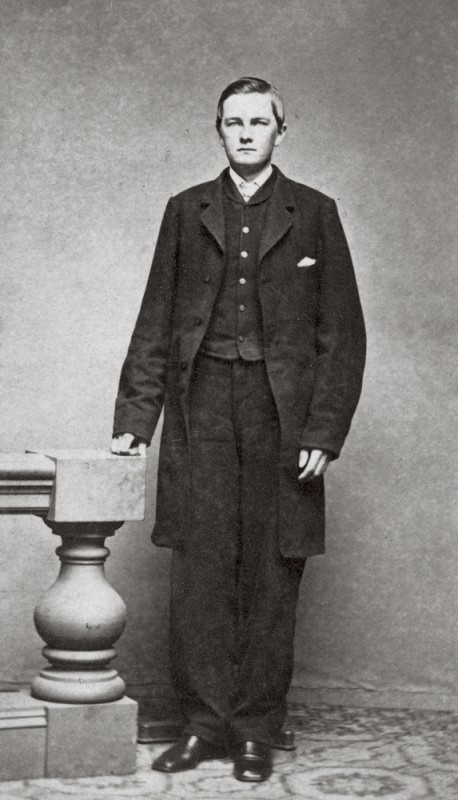

Tilghman Vestal, photo taken in 1866 by H. G. Pearce, Providence, Rhode Island. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.)

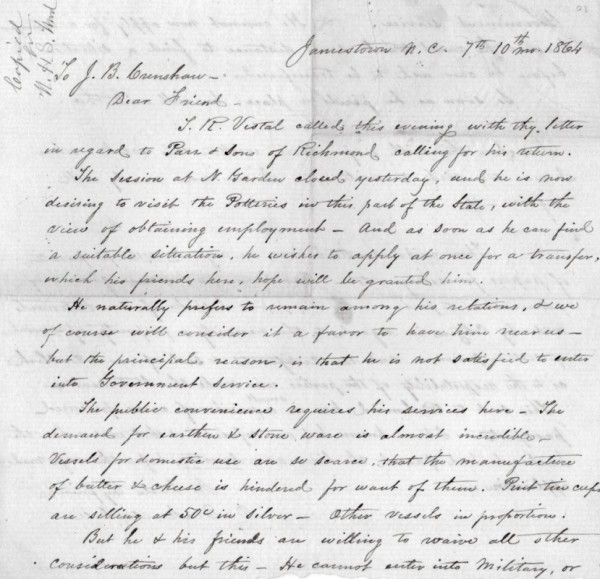

Letter from Delphina Mendenhall to J. B. Crenshaw, October 7, 1864. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.) The letter describes the difficulty in acquiring pottery.

Fat lamp, attributed to the William Hockett/Hoggatt family of potters, northern Randolph/southern Guilford County, North Carolina, ca. 1860. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.)

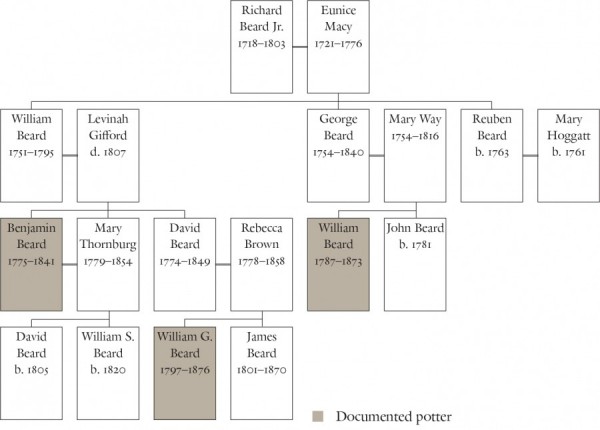

Beard Family of Potters. (Compiled by Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

n Documented potter

Jar, Benjamin Beard, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1810–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 11/16". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the unusual pulled and pinched handle on the jar illustrated in fig. 52.

Detail of the impressed mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 52.

Deep River Friends Meeting, Deep River Community, Guilford County, North Carolina, 1873–1875. (Courtesy, Friends Historical Collection, Guilford College.) The meetinghouse was built using 133,000 bricks made of clay dug at Benjamin Beard’s land.

Research of Quaker potters in North Carolina has been limited due to the scarcity of signed wares and identifiable pottery sites. Because these craftsmen typically lived in agrarian areas, supplemented their trade with farming, and led rather plain lifestyles, it has been assumed that their production was largely limited to utilitarian ware. That hypothesis is changing with the discovery of more pottery sites, kiln structures, genealogical and historical research, and documentation and reattributions of extant wares.

The Religious Society of Friends originated in 1644 in Leicestershire, England.[1] In 1650, after he and his followers were charged with blasphemy, founder George Fox told the judges to “tremble at the word of the Lord,” whereupon Justice Gervase Bennet of Derby reportedly referred to the Friends as “Quakers.”[2] Quakerism has been described as “primitive Christianity revived.” Believing an “inner light” would guide the conscience, their basic tenets were to refuse to fight or swear, to pay no tithes, to acknowledge no man as master, and to make no distinction between clergy and lay persons. The teachings of Fox and the beliefs of the Quakers originally spread through northern England and then throughout the country, eventually progressing to Scotland, Ireland, Wales, the West Indies, and America.[3]

In England, Quaker meetinghouses were often located in and around pottery centers such as Staffordshire and Bristol. Several British Quakers achieved acclaim in the field of ceramics, including chemist and pottery manufacturer William Cookworthy and his cousin Richard Champion, who pioneered the early porcelain industry in England. In the colonies, Joshua Tittery began making earthenware in Philadelphia by 1698, and the Osborne family followed suit in Essex and Bristol counties, Massachusetts, by the 1740s. By the end of the eighteenth century, many Quaker potters were active in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia.[4]

In the mid- to late eighteenth century there was a large migration of Quakers into North Carolina. These families left the mid-Atlantic and New England states and traveled down the Great Wagon Road and Colonial Trading Path from such areas as Philadelphia and Nantucket, carrying with them the cultural knowledge and techniques of ancestors and relatives. Areas of poor soil, unsuitable for productive farming, produced an abundance of “fat” clay, useful for turning pottery, as well as the raw minerals required by farmer-potters for the decoration and glazing of their wares (fig. 1).

Quakers were required to obtain “certificates of removal” if they left their congregation, known as meeting: “All Friends removing out of the limits of their monthly meetings, whether for continuance, or for any considerable length of time, are advised to apply to their respective meetings for certificates directed to those within which they propose to sojourn or settle.”[5] Surviving certificates of removal have made possible the tracking of a family’s movement from one area to another.

Members of the Society of Friends were required to marry within their religion or relinquish “their right in society, and monthly meetings may accordingly disown them.”[6] This requirement, among others, resulted in close-knit communities with intertwined families, encouraged ongoing contact among Quaker meetings and settlements, and created opportunity for the emergence of a ceramic tradition.

The Dennis Family

Thomas Dennis (b. ca. 1650) was living in the county of West Meath, near Athlone, Ireland, by 1673. He had two children by his first wife, whose name is unknown. In 1681 Thomas married his second wife, Jane Tatnall, in Edenderry, Ireland. The following year, the couple immigrated to western New Jersey and settled with other Quakers on a 64,000-acre tract of wilderness in Gloucester County called the Irish Tenth. In 1684 Thomas received forty acres on Newton Creek, near present-day West Collingswood.[7] About 1687/88 he rented a lot on the south side of Walnut Street, east of Fifth Street, in Philadelphia, and purchased adjoining land to the east in 1692. Shortly thereafter, Thomas moved back to Gloucester County, New Jersey, where he most likely resided until his death in 1720.[8]

Thomas and Jane had two boys and four girls. Thomas II was born to them about 1700 (fig. 2), and in 1720 married Sarah Wyeth. They lived in Gloucester County, New Jersey, until 1728, when they moved to Chester County, Pennsylvania, with their sons, Thomas III (b. 1724) and Edward (b. ca. 1726). In 1748 Thomas II purchased a 263-acre tract in East Fallowfield Township in Chester County.[9] Thomas III married Elizabeth Webb, daughter of Joseph and Ann Willis Webb, of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1757, after which he and his wife evidently continued to live with his parents on their 263-acre tract. In 1766 Thomas II sold his land and moved, with his wife and his son Thomas III’s family, to North Carolina.[10]

These two families settled on a 300-acre tract in what is now north-central Randolph County, North Carolina. The property was bounded on the southeastern side by Polecat Creek and sat astride the Trading Road—formerly the Indian Trading Path—that ran from Petersburg, Virginia, to South Carolina (fig. 3). In his will probated in 1775, Thomas II bequeathed his land to his wife and Thomas III.[11] On April 19, 1779, however, Robert and William Rankin received a grant encompassing that land, which Thomas III had to forfeit after refusing to swear an Oath of Allegiance and fight in the Revolutionary War.[12] Like many other Quakers, he was treated harshly for his pacifist beliefs. He was able to buy his property back after the war, and in 1786 a new state land grant for the 300-acre tract was issued in his name.[13] After his death in 1803, this property passed to his son, William (1769–1847).[14]

William Dennis had married Delilah Hobbs, daughter of Elisha and Fanney McLana Hobbs, on May 16, 1790.[15] They had three girls and seven boys. The eldest son, Thomas (1791–1839), who was born in Randolph County, North Carolina, followed his father in the potting trade. William lived on Thomas III’s land, and in 1796 he purchased, from his aunt Rachel Dennis and her sons, 100 acres of property that adjoined the east side of his father’s property (see fig. 3). He acquired an additional 60 acres in 1800, and three years later inherited the family’s 300-acre homestead.[16] In his will, Thomas III also left William the “remainder of [his] . . . moveable or personable estate & effects, goods & chattles both within doors & without with all debts due to me.”[17]

William Dennis was a member in good standing of the Society of Friends. He attended Centre Monthly Meeting and in 1815 donated property for the establishment of Salem Friends Meeting under the auspices of Marlborough Monthly Meeting, where he was appointed first clerk.[18] Like many Quakers, William was opposed to slavery. He was a member of the Manumission Society, for which he served as a delegate and representative to several meetings between 1819 and 1828.[19] William’s views on the equality of men may have influenced his acceptance of George Newby, an African American youth, as an apprentice in 1813.[20] Newby’s indenture is the earliest written evidence that William was a potter (fig. 4).

North Carolina Quakers occasionally apprenticed their children to Friends in other states. In 1794, for example, Richard Mendenhall of Jamestown, North Carolina, was sent to Chester County, Pennsylvania, to learn the pottery-making trade.[21] Since William Dennis remained at Centre Monthly Meeting throughout his youth, it is likely that he apprenticed with a local potter. The occupation of William’s father is not known, but his grandfather was listed as a cordwainer in an early New Jersey deed, and as a yeoman in his will. Deeds in New Jersey and Pennsylvania indicate that Thomas Dennis I worked as a shoemaker.[22]

Of the Quaker potters in North Carolina, those most likely to have trained William Dennis are members of the neighboring Dicks or Hockett (Hoggatt) families. William and Randolph County potter Peter Dicks (b. 1771) both attended Centre and Marlborough Monthly Meetings and traveled together later in life, journeying to Tennessee and Indiana in 1825 and 1826.[23] As commissioners, the two men helped lay out and sell lots for the town of New Salem in 1816.[24]

William Dennis’s land acquisitions suggest that he farmed until at least 1820, when he moved to New Salem and built a house on lot 4 (fig. 5).[25] Before moving to Indiana in 1832, he sold Peter Dicks the property on which his original home and pottery were located.[26] In September of that year, Dennis, his wife, and son, Nathan, were granted certificates from Marlborough Monthly Meeting to Springfield Monthly Meeting in Wayne County, Indiana. The Springfield Meeting accepted them the following month.[27]

There is no evidence that William Dennis made pottery after arriving in Indiana; indications are that he continued to farm and actively campaign against slavery. The Springfield Monthly Meeting disowned him in 1844 for joining the “separatists”—abolitionist Friends whose more radical anti-slavery approach led them to establish separate meetings—but reinstated him two years later. In a letter of apology, William wrote:

Whereas, I have had a birthright in the Society of Friends upwards of seventy years, but for the want of attending to the manifestations of truth in my own breast, I have given way so far as to be led by the reasoning of others as to unite in setting up separate meetings and attending them; for which I have been disowned; which has caused me for months past to feel sorrow; now I feel very desirous that Friends would pass by my offense, and receive me into the unity of the Society again, and the love of Friends as I once was.[28]

William died the following year, at the age of seventy-seven.

In 1812 William’s son Thomas purchased from William Welborn a 164-acre tract adjoining the north side of his father’s property.[29] The following year Thomas married Elizabeth Wilson, daughter of Jesse and Elizabeth Beeson Wilson, at Providence Friends Meeting under the auspices of Centre Monthly Meeting. Three of the witnesses to the marriage—William Dennis, Mahlon Hockett, and Peter Dicks—were potters; apparently none of Thomas and Elizabeth’s ten children became potters.[30]

A published biography of this Thomas Dennis states that, “In his early life he followed farming until he was near twenty years of age, when he commenced to learn the potter’s trade, which he followed with that of farming until his removal to Wayne County, Ind., landing Oct. 1, 1822, in the city of Richmond.”[31] This account and archaeological evidence (figs. 6–8) suggest that Thomas learned to make pottery by 1811; soon thereafter he established his own shop, which he continued to operate seasonally for eleven years before moving from New Salem to Indiana. Earthenware fragments and kiln furniture from his site (figs. 6-8) resemble those associated with his father, William Dennis, who probably taught Thomas the pottery trade (figs. 9-11). If Thomas opened his own shop following his marriage in 1813, it may explain his father’s need to take George Newby as an apprentice that year.

Before departing to Indiana, Thomas sold 164 acres containing his pottery shop and clay beds to Edward Bowman.[32] Although it is not known why he left North Carolina, a nineteenth-century history of Wayne County suggests that slavery was the primary catalyst: “Mr. Dennis was an active member of the Society of Friends . . . [and] could not bear the idea of rearing his children in the midst of slavery.”[33] A descendant also points out that good farming land was available in Indiana.[34]

It is not known whether Thomas continued to produce earthenware in Indiana, but Eleazar Hiatt operated a pottery in Indiana from about 1818 to at least 1824. Originally from Guilford County, North Carolina, Hiatt employed a minimum of three potters: John Scott, George Bell, and Isaac Beeson.[35] The latter journeyman was likely the same Isaac Beeson who had apprenticed with Peter Dicks in Randolph County, North Carolina, beginning in 1806.[36] Thomas subsequently settled on a 154-acre tract in Dalton Township, also in Wayne County. He was appointed county treasurer in 1839 but died while in office, at the age of forty-seven.[37]

George W. and Moses Newby

George W. Newby was born in Randolph County, North Carolina, about 1801. According to historian Paul Heinegg, both George and potter Moses Newby (b. ca. 1782) were part of the Peter Newby family, six “free persons of colour” according to the 1800 census of Randolph County.[38] Quaker owners had freed several members of the Newby family prior to that time. In 1805 the Guilford County Court gave Moses his freedom, acknowledging that Quakers had emancipated his parents.[39]

William Dennis took George Newby as an apprentice in 1813 (see fig. 4).[40] According to Friends’ annual meeting records, several African American youths had been placed under the care of members to acquire “a suitable education to enable them to minister to their own necessities, and fit them for the enjoyment of freedom.”[41] The terms of Newby’s indenture required that he be bound out and taught the trade of a potter until the age of twenty-one. This apprenticeship would have ended in 1822, the same year William’s son Thomas moved to Richmond, Indiana. Although there is no evidence that Newby left with Dennis, the former was in Richmond by 1830.[42] Newby married a woman named Agnes, and in about 1837 they had a daughter, Elliana, and continued living in Richmond until at least 1840.[43] By 1850, however, the family had moved to the Cabin Creek Settlement in western Randolph County, Indiana, a community composed of 80–100 African American families from North Carolina and Virginia.[44] The census taken in that year lists Newby as a blacksmith and indicates that he could read and write.[45] By the time of the 1860 census he had purchased four acres of land in West River Township and was listed as a farmer.[46] Four years later he sold this property and four adjoining acres to his neighbor Eli Townsend,[47] then moved to Van Buren County, Michigan, where in 1870 he was recorded as a farmworker living in Arlington Township.[48]

Moses Newby was born to free parents about 1782.[49] In August 1798 he was apprenticed to John Bullock of Orange County, North Carolina, to learn the potter’s trade (fig. 14).[50] Six years later a Guilford County court reaffirmed Newby’s status as a freeman:

It appearing to the Satisfaction of the Court here that Moses [Newby], a man of Colour, . . . was born [to] parrents emansipated by people called Quakers, tho no record of [this] . . . can now be found and it further appearing to the Court that the said man Mosses is of a fair moral charecter and Enquiring the trade of a potter which he Learned as a apprentice under John Bullock, late of Orange County. It is ordered that the said Moses be emansipated [and] . . . be entitled to all the rights previleages of a free man of Colour according to the Laws of North Carolina.[51]

This ruling was issued about two years after the end of Newby’s apprenticeship. The absence of later records pertaining to him suggests that he may have left North Carolina.

Henry Watkins

Henry Watkins, the son of William and Lydia (maiden name unknown) Watkins, was born in Randolph County, North Carolina, in 1798 or 1799. He was accepted into the Marlborough Monthly Meeting on November 1, 1817, and two years later married Elizabeth Elliot, daughter of Obadiah and Sarah Chamness Elliot.[52] The Randolph County tax list for 1820 indicates that Henry owned lot 8 in New Salem.[53] Later, he purchased lots 9, 10, and 11, which were east of lot 8.[54] In 1821 Henry took his brother Joseph Watkins as an apprentice to the potter’s trade. Joseph had been formerly bound in 1818, to Seth Hinshaw in the hatter’s trade (fig. 15).[55] This bond is the earliest record of Henry being a potter.

Henry Watkins may have apprenticed with William Dennis or with his son Thomas, or perhaps worked at one of their potteries as a journeyman. Henry lived two miles from the Dennises, attended the same Quaker meeting, and witnessed the marriage of William’s daughter Mary to Simeon McCollum in 1816.[56] Watkins was clearly working independently by the time of his brother’s apprenticeship in 1821. That date corresponds with Thomas’s disposition of property in preparation for his move to Indiana and William’s establishment of residence in New Salem. Thomas’s departure would have lessened competition and perhaps gave Watkins incentive to remain in the pottery trade in New Salem.

In 1824 Henry Watkins bought 100 acres of land on the north side of William Dennis’s 300-acre tract.[57] Nine years later he purchased a sixteen-acre tract from William’s son Absalom.[58] This tract adjoined the north side of property formerly owned by William, and the west side of property formerly owned by his son Thomas. About 1837 Watkins moved to southern Guilford County, where he bought a one-hundred-acre tract formerly belonging to his brother-in-law John Beard.[59] He continued making pottery there and is listed as a potter in the 1850 census of Guilford County.[60] Henry subsequently moved back to northern Randolph County, where the 1860 census lists him as a miller, living near potter Himelius Hockett.[61] Watkins was one of ten neighbors who in May 1863 signed a petition to Jefferson Davis seeking to exempt Hockett, his brother Jesse, and two other Quakers from having to serve in the Confederate Army. All were being held in a Confederate prison in Kinston, North Carolina, after refusing to bear arms.[62]

Fortunately, pottery documented and attributed to Henry Watkins survives. A two-handled jar with its bottom boldly signed in script (figs. 16, 17), along with a dish and fat lamp likely made by him, descended through a family living near New Salem in Randolph County. The dish was splashed with copper green over the natural buff clay background and covered with a clear lead glaze (fig. 18). The fat lamp, decorated with an incised sine wave around the cup, shifted in the kiln and, as a result, fired upside down, which caused the heavy lead glaze to run and form drips on the handle and rim of the cup. Another fat lamp, with a similar style, has been attributed to Watkins (fig. 19).

The Dicks Family

Family tradition maintains that Peter Dicks (ca. 1720–1796) was a potter.[63] He moved to present-day Guilford County from Warrington Meeting in York County, Pennsylvania, in 1755 and settled on a 640-acre tract of land located “on both sides of the upper fork of Polecat Creek.”[64] Peter and four other early Quaker settlers—William Hockett, Isaac Beeson, John Beals, and Matthew Osborne—organized Centre Monthly Meeting, and Peter gave the land on which the meetinghouse was built.[65]

The Hockett and Beeson families were also involved in the pottery trade, and some of the four families mentioned married into the Dicks families (fig. 20). Three of the five children born to Peter Dicks’s son, James (ca. 1748–1830), were associated either directly or indirectly with the pottery trade: Peter (1771–1843), William (1773–1839), and Elizabeth (1775–1816). Peter, discussed below, has been documented as a potter through an apprentice indenture and estate inventories. Although William’s profession is not known, his son Nathan (1794–ca. 1834) is reputed to have been a potter, and his grandson Cornelius (1818–1894) and great-grandson Nathan (1855–1918) are documented as having worked in that trade. Elizabeth Dicks married Thomas Beard, a potter in Guilford County, North Carolina.[66]

Peter Dicks, who was born in Guilford County, married Ann Hodson, the daughter of Joseph and Margaret, at Centre Monthly Meeting on October 26, 1797. The couple moved to north-central Randolph County, purchased land in 1804, and in 1806 established an oil and gristmill on the Deep River.[67] In November 1806 Peter took eighteen-year-old orphan Isaac Beeson as an apprentice in the pottery trade (fig. 21), an agreement set to expire when Beeson reached the age of twenty-one.[68] In 1816 Peter was one of five commissioners appointed to lay out and sell lots in New Salem.[69] The town was located approximately one mile northeast of his mill on Deep River. Like many of his Quaker brethren, Peter Dicks was innovative and entrepreneurial. In addition to potting, he served as a minister and member of the Manumission Society, worked as a merchant in New Salem, and farmed several tracts of land he owned nearby. He bought the Dennis family farm and pottery when William Dennis moved to Indiana in 1832.[70] The duration of Peter’s career as a potter is not known, but his estate inventory taken on May 23, 1843, noted the sale of “1 pair pipes moles” to his son James for $1 and debts of $6.52 and $10.03 owed by Henry Watkins and his brother-in-law John Beard, respectively. Peter’s estate sold additional pottery equipment to his son James Dicks the following year, including “1 potters Lathe & glaseing mill” valued at $5.00.[71] Despite his purchases of pottery equipment, there is no physical evidence that James made pottery.

William Dicks’s grandson Cornelius first made pottery in southern Guilford County, where he also attended Centre Monthly Meeting. In 1841 he was disowned for marrying Eunice Margaret Blackburn out of unity. The 1850 and 1860 censuses for the Southern Division of Guilford County list Cornelius as a farmer, but an account of his earthenware production written by R. R. Ross in 1927 suggests that he also made pottery:

Up the County line about a mile you will find a deposit of potter’s clay of the best variety. There were two potter shops near by, H. M. Hocket in Randolph, and C. T. Dicks on the Guilford side, much of the ware that was used in the homes was made at these shops. It was also hauled in wagons for many miles, and had the reputation of being the red ware that would stand fire, and was used for cooking vessels in many of the kitchens at that time. No pot or kettle has ever been made that would cook dried fruit and pumpkins like the old red stew jars that our mothers and grandmothers used, and no dish has ever been found that would cook a chicken pie for a corn shucking like the old dish made by Hocket and Dicks.[72]

Soon after 1860 Cornelius Dicks moved to New Market Township in northern Randolph County and established a residence and pottery near Plank Road, which ran from Fayetteville to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, on property he had purchased at an earlier date. According to his granddaughter, Nettie Dicks Lamb (b. 1900), he “made [pottery] . . . for years, because I heard dad tell about getting in the wagon and taking it . . . down to Fayetteville and selling . . . big loads . . . he went with him many times down the Plank Road.” Lamb also noted that her grandfather made a variety of utilitarian wares including “things you cooked with . . . crocks, churns, [and vessels for] . . . molasses” as well as some decorative objects, including “a great big old [brown clay] duck” that her mother “kept setting on her fireplace.”[73] Cornelius also made press-molded smoking pipes (fig. 22). After his death, his daughter, Mary Elizabeth Dicks Davis (1842–1920; fig. 23), inherited his press and continued to make pipes, firing them in the coals of her wood cookstove (fig. 24).[74]

Cornelius was living in his son Nathan’s house in New Market Township when he made his will in June 1891.[75] The federal census describes Nathan (1855–1918) as a potter in both 1880 and 1900; in the latter he was described as a manufacturer of “fire proof ware.”[76] The 1910 census states that Nathan was a potter in Greensboro, Guilford County, and that he rented his property.[77] Nevertheless, Nathan appears to have returned to Randolph County occasionally. According to Iro Swaim (b. 1908), who lived next door to Nathan as a child, the potter came “out here in front of the house and [dug] . . . clay to make . . . dishes, and crocks, and . . . things like that.”[78]

Another local resident, Eleanor Hartley (b. 1903), described buggy rides past Nathan Dicks’s pottery and recalled that he would roll up the slatted blinds on his porch to display new wares.[79] Like many rural potters, Nathan made forms similar to those produced by earlier members of his family. The jug illustrated in figure 25 bears the inscription “N. B. DICKS. new market n.c. Jan 12 1890 1 Pt,” has an iron tinted lead glaze over a buff-colored body, and concentric and wavy lines incised on the shoulder. One could imagine this jug, a gift to one of Nathan’s friends, having been made nearly one hundred years earlier.

A bulbous-handled earthenware skillet with a history of use in the New Market community could be an example of Dicks’s “fire proof ware” (fig. 26). Its green lead glaze is spotted as a result of impurities in the clay. A similar glaze can also be seen on a pitcher that descended in a local family and reportedly was made by Dicks (fig. 27). The pitcher has the same incised line decoration as the signed jug, and the handles of both vessels exhibit elongated lower terminals like those on the storage jars illustrated in figure 28. Surface artifacts at the Nathan Dicks pottery site revealed fragments having glazes and clay paste similar to his surviving pottery (fig. 29).

The Beeson Family

After serving his apprenticeship with Peter Dicks, Isaac Beeson (1788–1869) married Sarah Gorrell on June 6, 1811, in Guilford County, North Carolina. During the early 1820s they moved to Richmond, Indiana, where he worked at Eleazor Hiatt’s pottery.[80] The 1850 census of Wayne County shows that Isaac and his son Mahlon were making pottery at that time.[81] Soon afterward, Isaac moved to Hancock County, Indiana:

In the early fifties Isaac Beeson established a pottery . . . on the site now occupied by the Western Grove Church. He made jars, jugs, etc., from clay, which, after being burned in a kiln, were dipped in a solution and then burned again until glazed. The potter’s wheel was in operation for about nine years.[82]

According to an early history, Beeson also made some of the first clay drainage tiles in Hancock County:

They were round tile, turned by hand on a potter’s lathe. After being used for half century they were taken up and found in good condition. Some of them may now be seen in the geological museum at the State House at Indianapolis. In 1863, Jacob Schramm built a tile factory on his farm in the German Settlement, in Sugar Creek Township, and manufactured what were known as “horseshoe” tile. It had no bottom, but was constructed with two sides and a top, on the principle of the board drains. . . . Just about the close of the Civil War the “horseshoe” tile were replaced by flat-bottomed tile, which were continued in use for a period of fifteen or twenty years. They are familiar to most people of the county, and may still be excavated in repairing the older ditches. During the eighties round tile came into general use and since that time have been used almost exclusively in our covered ditches.[83]

Schramm’s flat-bottom drainage tiles appear to have been similar to the extruded examples made by David Hockett of Randolph County, North Carolina, during the same period (see fig. 40). In the 1860 census for Hancock County, Beeson and his son John were listed as potters living in the same household. Isaac’s son Mahlon had moved to Hancock County by then, although he was listed as a farmer.[84] In 1864 Isaac Beeson sold his pottery shop to the Society of Friends for the establishment of Western Grove Preparatory Meeting.[85]

The Hoggatt/Hockett Family

Oral tradition suggests that Philip Hoggatt (ca. 1687–1783) may have been a potter, but no documentary evidence pertaining to his trade has been found. He settled on Richland Creek, a tributary of the Deep River, in what is today southwestern Guilford County, North Carolina.[86] Philip had two sons, William and Joseph, whose descendants were unquestionably potters (fig. 30). William (1727–1772) and his family settled “on the Middle Fork of Polecatt, near the Head Waters of Deep River, about 3 Miles, North Of the Trading Path” in northern Randolph County, North Carolina.[87] Their arrival probably coincided with that of Peter Dicks (ca. 1720–1796).

An 1878 journal entry by William (now Hockett) III (1799–1880) indicates that his grandfather may have been a potter: “John Hockett son of [William I] . . . was born the 16th day of the 2nd month 1771, and died about the 5th month 1772 by getting badly burned at the clay oven on the coals pulled out.”[88] Tragically, John likely fell or crawled onto excess coals removed from the firebox during the firing of the kiln. Pottery kilns are still referred to as “clay ovens” by some longtime residents of Randolph and Guilford counties.

A small dish that descended through several generations of the Hockett family bears the pencil inscription “Made from Clay on Henry Clay Gregson’s Farm” (fig. 31). Gregson’s farm, which remains in his family today, was near William Hoggatt I’s land grant. The double booge rear profile, heavy undercut rim, and decoration of the dish suggest that it dates from the eighteenth century. The maker coated the buff-colored body with white slip, then applied copper and manganese sponging. After the slip dried, he coated the front with a clear lead glaze. Migration of the glaze indicates that the dish stood on end during firing.

An earthenware bottle attributed to William Hockett III (fig. 32) bears the incised inscription “WM RR H 4-19-1879” (fig. 33). Presumably, “WM” signifies his first name, “RR” signifies the first and middle names of his thirteen-year-old granddaughter Rachel Rodema (1866–1944; fig. 34), and “H” signifies their last name (Hockett). According to family members, William III turned the bottle and Rachel decorated it with an incised design that seems to be a tree or a flower. Rachel was the daughter of potter Himelius Mendenhall Hockett (1825–1913) (fig. 35), who reputedly used it to store coffee beans.[89] Himelius married Rachel Branson (1830–1903), daughter of John and Jane Cox Branson, on May 6, 1852.[90]

Hockett family tradition maintains that the earthenware chest illustrated in figure 36 was made by William III as a gift for Himelius.[91] The maker rolled out slabs of clay and cut them into rectangles for the sides, back, and bottom, but turned the top on a potter’s wheel. After cutting the top and adding a slab to its underside, he shaped the side peaks and feet, assembled the pieces, and inscribed the date, 1828, on the front. Although the potter probably used the same glaze for the lid and the case, the lid has a more unified green surface.

The 1850 census for Randolph County states that Himelius Hockett was a teacher living in the household of his father, William III.[92] In the census a decade later he is described as a farmer living with his wife, one child, and Harper Parson at residence number 725, which was near the home of Henry Watkins.[93] Harper Parson (b. ca. 1842) has been identified as a laborer in Himelius’s pottery.[94] A November 1863 letter to Himelius from his daughter Nancy Maria (b. 1858) and son Cyrus Elwood (b. 1860) reported on their mother caring for Watkins’s ailing son:

My Dear Pappy, as mother has sent thee [several letters] . . . I will try to send thee one to [tell] . . . thee what we are . . . [doing] at this time we are all well all though mother suffer a grate deal with her old complaint tho she is able to work all they time she is ___ go backerds and forward to H. Watkins to sit up with Franklin He is sick with the tyfoid fever an dont look like he will last the weak out.[95]

On April 4, 1862, Himelius and his brother Jesse Davis Hockett were conscripted into the Confederate Army. Because they would not bear arms, they were tortured and imprisoned at Kinston, North Carolina. John Branson, Himelius’s father-in-law, sent a petition to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, requesting the release of the Hocketts and two other men (fig. 37).[96] Due to the scarcity of paper during the war, Branson used a page torn from an old account ledger recording the sale of earthenware pottery (fig. 38).[97] Himelius and his brother were discharged from the Confederacy, after the Society of Friends paid for their release.[98]

Himelius lost his vision in his later years, and his granddaughter Carrie Hockett Cox (b. 1899) remembered reading to him as a young girl: “I learned to read by reading to him. He couldn’t see, you know, but he could tell me what chapter in the Bible to read.” Cox thought her father, William Wilburforce Hockett (1871–1947), had also been a potter: “Way before I was born . . . I think he made a little . . . [but] he didn’t burn it.” She recalled a building referred to as the “potter shop,” which was “across the old road in front of their house” and an old kiln where their chickens laid eggs. Cox also believed that “they made brick” in addition to “pottery . . . crocks . . . flower pots and things like that.” The pottery was “nothing fancy . . . sort of like clay, brown” (fig. 39).[99]

Himelius Hockett’s brother Milton (1829–1902), who lived north of Himelius’s residence and shop, near the Randolph/Guilford County line, was also an earthenware potter.[100] Although there is no documentary evidence or oral tradition that their brother Jesse Davis Hockett was a potter as well, Jesse’s son David Franklin Hockett (1848–1926) made brick, earthenware, and extruded earthenware drain tiles (fig. 40).[101]

Remnants of David Hockett’s kiln are situated on the sloping south side of a hill and, at first glance, resemble a rock wall (fig. 41). The nearly square kiln, 10 by 9 1/2 feet, was built into the hillside to provide insulation and structural support. The outer shell was made of local rock, and the interior lining was made of soft, fire-resistant, talceous schist—a stone occurring naturally in the region (fig. 42). Both the interior and the exterior rock surfaces appear to have been dry-stacked without the benefit of mortar. The rock was corbelled near the upper part of the kiln to close off the top. A single flue channel is visible running under the kiln remains and a piece of strap iron on the front wall indicates the location of an access opening. Local residents remembered the kiln being approximately seven feet tall with a firebox extending out the front and a smokestack made of clay or metal (fig. 43). One individual, who described the smokestack as a clay cylinder, also recalled seeing red clay pottery with the initials “DFH” scratched in the bottom near the site.[102] According to another neighbor, David Hockett’s kiln was

rock all the way over . . . there was a hole . . . in the center of it, maybe a foot across . . . it was a furnace looking thing, and I reckon that is what they had. They fired it from the outside . . . heat would expand up into it. There was a door, looked like about two and a half to three feet square. . . . I believe you went in over the firebox. . . . It set out facing the south there, the firebox, and the hole was right up over that firebox, I remember.[103]

In shape and size, Hockett’s kiln was comparable to that built by William Dennis approximately three miles south (fig. 44).

Philip Hoggatt’s son Joseph (ca. 1735–1815) remained in the vicinity in which his father had settled. He married Phebe Haworth on January 6, 1763, and had a son named Mahlon (1772–1850), who lived and made pottery within the present-day city limits of High Point, North Carolina. According to one descendant, Mahlon’s shop was near the old Highland Cotton Mill: “[He] didn”t make fancy stuff . . . he preached and worked in the church, and just made [pottery] . . . when somebody wanted something. . . . [If] they told him they wanted a big pot, and he went out and made that for them.”[104] Mahlon’s son and namesake (1808–1880) was also a potter, as indicated in the 1850 census for Guilford County.[105] Mahlon II is listed as a farmer in the 1860 census for Randolph County.[106] By 1880, however, he had moved to Indiana and was living in Ripley Township of Rush County, where he was listed as a farmer in the census for that year.[107]

The Mendenhalls

George Mendenhall was born on July 21, 1751, in Bradford, Pennsylvania (fig. 45). He moved to North Carolina with his parents, James Mendenhall (1718–1782) and Hannah Thomas Mendenhall (1717–1798), and later married Judith Gardner, whose birthplace was Nantucket, Massachusetts. Mendenhall organized and laid out the town of Jamestown, North Carolina, which was named in honor of his father.[108] In 1794 George sent his fifteen-year-old son Richard (1778–1851) to Jesse Kersey (1768–1845) of Chester County, Pennsylvania, to learn the potter’s trade; an older son, Stephen, went to York County, Pennsylvania, to apprentice as a tanner.[109] Kersey was a member of the Bradford Monthly Meeting, which accepted Richard Mendenhall’s certificate from the Deep River Monthly Meeting in August 1794.[110] Kersey, who had apprenticed with Philadelphia potter John Thompson from 1784 to 1789, had just set up shop in Brandywine Township when Mendenhall arrived. Other workers at Kersey’s pottery included Mendenhall’s second cousin, Jonathan Howell Mendenhall, and Aaron Fraisure.[111] According to Richard Mendenhall, “Jonathan [Mendenhall] taught me all the Latin he could, and I repeated lessons while I was grinding clay.”[112]

After Kersey sold his pottery shop and equipment in 1795, Richard Mendenhall “went to York[, Pennsylvania, and] learned tanning with Herman Updegraff . . . and . . . his son-in-law, and Jonathan [Mendenhall] continued at potting with Thomas Vickers,” who worked at East Caln Township, Chester County.[113] Richard subsequently returned to Jamestown, operated a tannery, and built a brick store building across the road from his residence (figs. 46, 47). He apparently learned enough during his apprenticeship with Kersey to establish a pottery on a one-half-acre lot he owned in Jamestown.[114] In 1842 Mendenhall sold the lot “known under the appellation of the potter Shop Lot together with all of the . . . appurtenances” to William Lamb for $125.[115] Noah Cude Jerrell (Jerrol) (1820–1909) and Isaac Potter (ca. 1787–1864) are thought to have been living at or near the shop.[116] Both men are listed as potters in southern Guilford County in the 1850 census.[117] Noah’s residence was near that of William Hockett III, in the Centre Monthly Meeting area. Noah’s sister Elizabeth Caroline was married to potter Samuel Vestal Barker (1814–1865), whose mother, Elizabeth, was the sister of potter Messor Amos Vestal (1812–1886), who married Richard Mendenhall’s daughter, Rhoda. Samuel Barker is also listed as a potter in the 1850 census for southern Guilford County, but lived outside the Jamestown area.[118]

Born about 1787 in Somerset, Maryland, Isaac Potter, possibly a journeyman at Mendenhall’s pottery, married Nancy Gossett in December 1814; she died eight years later. In 1819 he purchased a 165-acre tract adjoining Mendenhall’s property from David Beard as well as two additional adjoining tracts, totaling slightly more than 138 acres, from James Talbert.[119] Presumably all those tracts were used for farming or animal husbandry. On January 16, 1827, Potter married Lois Kersey, Jesse Kersey’s first cousin. Although tenuous, connections of this type lend credence to the theory that Isaac made pottery at Jamestown.[120]

Two other potters who were related to Richard Mendenhall through marriage may have been part of the Jamestown ceramic tradition. Hezekiah Clark (1797–1876) moved from Centre Monthly Meeting to Deep River Meeting in January 1817. Two years later he married Mendenhall’s younger sister Abigail, who had been given several lots in Jamestown and was “by trade a bonnet and glove-maker, and before marriage, taught school.”[121] Abigail and Hezekiah began attending New Garden Meeting in Guilford County after their marriage, but in 1823 returned to Centre Monthly Meeting.[122] According to a late-nineteenth-century history of Clinton County, Ohio,

[Hezekiah] was a tanner by trade, and while in North Carolina, carried on a tanyard, blacksmith and potter shop, besides farming. He himself wagoned down through South Carolina and Georgia, hauling off leather and other goods, and attended different fairs that were held where he disposed of some of his stock. The tanshop was accidentally burned, when he sold out and moved to the then far West, with his family of nine children.[123]

Messor Amos Vestal (1812–1886), the son of Jesse Vestal, is another potter who might have worked in Richard Mendenhall’s shop. Messor married Richard’s daughter Rhoda on February 9, 1833. Because Messor was not a Quaker, the Deep River Meeting disowned Rhoda for marrying out of unity. Later that year, she condemned her marriage and was accepted back into Deep River Meeting. In 1835 Messor and Rhoda moved to Surry County, North Carolina, where she received a certificate of removal from Deep River Meeting to Deep Creek Meeting.[124] The 1850 census lists Messor Vestal as a merchant in Surry County.[125] In 1859 the Vestals moved from the Surry (later Yadkin) County area to Maury County in central Tennessee, where they are recorded in the 1860 census.[126]

Messor’s son, Tilghman Ross Vestal (b. 1844) was a potter by trade (fig. 48).[127] In February 1862 Tilghman was conscripted into the Confederate Army. After refusing to take up arms, he was offered the chance to buy his way out of service. He wrote that “the superintendent of the conscript said I could be exempt by paying $500 to the Treasurer of the Confederate States or hire a substitute this I new before I was first arrested but I did not choose to buy an exemption furnish a substitute or give ade to the war in any way and as $500 in the treasury would aid it I concluded to risk the consequences & submit to the penalty of the law.”[128] Tilghman described his subsequent imprisonment and torture in vivid detail: “They began to pierce me with their bayonets I received 16 [wounds] . . . one of which was an inch deep the remainder about a quarter [inch deep] and still refused saying nothing could make me go to war I was then put on a dirt pile with a spade across my [knees].”[129] In November 1863 Vestal was sent to Castle Thunder—a tobacco warehouse that had been converted into a prison for civilians, spies, and political prisoners—in Richmond, Virginia. In a letter to John B. Crenshaw, a Quaker minister in Richmond, Tilghman stated that he was the grandson of Richard Mendenhall and would like to find an alternative to the service but “was reared in & now am of Friends faith and there by forbid from going into or buying an exemption from this war.”[130] Vestal’s aunt, Judith Mendenhall, and grandaunt, Delphina Mendenhall, also wrote to Crenshaw, and others, concerning Tilghman’s case. Crenshaw suggested that alternative service in the pottery trade might be an acceptable option and proposed that idea to Assistant Secretary of War, Judge Campbell.[131]

Quaker potter David Parr agreed to take Tilghman as a journeyman in his manufactory at Richmond, and Vestal consented on condition that he did not have to make items for the war effort.[132] Parr and Sons Pottery was listed as an earthenware manufacturer, but the company also produced stoneware.[133] In a letter to his aunt, Vestal wrote that he liked Parr’s pottery much better than his father’s.[134] When military operations in Richmond forced Parr and Sons temporarily to close, Tilghman received permission to go to Guilford County during the interregnum.[135] When the manufactory resumed production, Delphina Mendenhall sent a letter to J. B. Crenshaw requesting that Vestal’s place of service be transferred to Jamestown, which was in dire need of pottery (fig. 49).[136] Conscription for the war effort had left voids in all occupations. Richard Mendenhall’s granddaughter, Mary Mendenhall Hobbs (b. 1852) recalled, “We can scarcely realize how quickly supplies diminished when they could not be replenished. Table ware and cooking utinsels as well as farmers’ implements and Mechanics’ tools became scarce.”[137]

Delphina sent another letter requesting that Tilghman be sent to either Randolph County or Guilford County:

We wrote last week the great need there is of the Potter’s business being carried on here—next to the want of food & clothing, this country is suffering for want of vessels for domestic use. At [Tilghman’s] . . . request I enclose a form of permission for him to work in the counties of Randolph & Guilford—If that is too indefinite, then he asks for a permit to work with Enoch Craven of Randolph County N.C.—The first much preferred because a change may become necessary in case of Craven’s death, or other circumstances might render a change of location desirable.[138]

Vestal was unable to get transferred and eventually had to flee to Philadelphia to wait out the war’s end. If he had decided to return to Parr and Sons, his term would have been short. The pottery was destroyed by fire when the Confederate Army evacuated Richmond on April 3, 1865.[139] After the war, Vestal moved to Maury County, Tennessee, where he is recorded as a teacher living with his father.[140]

During the war and Reconstruction, some potteries were established in the Jamestown area to help alleviate the need for utilitarian wares. Mary Mendenhall Hobbs recalled that “There were potteries established in which earthen dishes were made, rough, but serviceable and foundries which manufactured pots, skillets, and ploughs.”[141] She also wrote of the need for fuel for lighting devices such as earthenware fat lamps (fig. 50):

tallow and . . . bees-wax were often difficult to obtain, and in our part of the State pine knots, which furnished our eastern fellow citizens with light were wanting. It was rather pitiful to see father close his books and sit before the fire. He determined to have a light by some means and asked “Uncle” Tommy to join him in a ’possum hunt. ’Possums have a very oily fat, and he thought that if he could get this, he might use it in a lamp. At first mother protested, saying, “The bush-whackers will think you are conscript hunters and will shoot you.” But when the time for the hunt came, and she saw the Nimrods preparing for the expedition, her anxiety turned to merriment, for two funnier looking persons never chased an Opossum. Both were tall men, father dressed in Quaker garb, plain coat and broad brimmed hat. “Uncle” Tommy always wore the Revolutionary Swallow tail. . . . As the two started out mother said, “When the ’possums see that outfit, I think they will come down.” Nothing came of the hunt, and father was obliged to find other material for his lights. For a time he used a queer little grease lamp, which was shaped very much as the lamp in Greek pictures, a little shallow bowl with a handle at one end and a lip at the other, the wick lying in the oil in the bowl and hanging out at the lip where it was lighted.[142]

The Beards

In 1772 Richard Beard Jr. (1718–1803), his wife, Eunice Macy, and their children moved from Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, to southwestern Guilford County, North Carolina. Together the couple had four sons and two daughters (fig. 51). Their son Reuben (b. 1763) married Philip Hoggatt’s daughter Mary. Their sons William (1751–1795) and George (1754–1840) were associated directly and indirectly with the pottery trade. William’s son Benjamin (1775–1841) was a potter, whose stamped signature has been found on the shoulder of a salt-glazed stoneware jar (figs. 52-54).[143] His pottery and clay pits were on land he inherited from his father (fig. 55).[144]

Some members of the Beard family were connected to the potter Amor Hiatt. In June 1822 David Beard (1774–1849), Benjamin Beard’s brother, was named as a trustee for his son William G. Beard (1797–1876), also a potter, concerning a loan to Amor Hiatt.[145] The terms of the agreement stated that Amor would pay back his debt of $90.70 1/2 to William on or before the first day of September 1823. Hiatt moved to Milton, Indiana, where he established a pottery shop, near that date. In a letter written before 1839, David Beard wrote his son James: “And as for thy Brother William—the last account they were well and doing about like they used to do—William preaching some, making hats, some potterer. And still having children.”[146]

George Beard had two sons, William and John. William (1787–1873) was a potter who married Rachael Pierson (Pearson) in Guilford County in September 1808. Eight years later William and his family moved to Union County, Indiana, where he lived until his death. A biographical and genealogical history published in 1899 states:

In his youth [William Beard] . . . had learned the potter’s trade, and this calling he followed . . . in connection with agriculture . . . . he was considered a man of much knowledge, and he not only practiced medicine for a period, but preached to congregations of the Society of Friends . . . for more than half a century.[147]

George Beard’s son John (b. 1781) was a businessman but may also have been involved in the pottery trade. He married Hannah Elliot, whose sister Elizabeth was Henry Watkins’s wife. Watkins purchased John Beard’s property in Guilford County in 1837, and both men were listed as debtors in the inventory of potter Peter Dicks.[148] In a letter of February 14, 1842, John’s first cousin David wrote: “George has left me—gone to John Beard’s to care of shop for him, and it is said that John is broke and has made a general surrender of all of his property—gold mines and all. His debts it is said are $4000. While his worth is $12,100 if they break in upon him and sell him out.”[149]

A Guilford County potter named Thomas Beard took Elliot Dison as an apprentice on December 15, 1809.[150] A Thomas Carson Beard (1768–1820) from Londonderry, Ulster Province, Ireland, married Elizabeth Dicks at Centre Monthly Meeting in March 1791.[151] Since Elizabeth was the sister of potter Peter Dicks, it seems likely that these Thomas Beards were one and the same. It should be noted that there were two separate Beard families in the Randolph/Guilford County area. Thomas Carson Beard was from a family that emigrated from Ireland to South Carolina and later moved to North Carolina.[152] He was not related to the Richard Beard Jr. family from Nantucket Island, Massachusetts.

The Quaker potters discussed in this article were accomplished craftsmen, entrepreneurs, and men of devout faith. Many were interrelated owing to the Quaker custom of marrying within the religion as well as their desire to preserve the secrets of their trade. Techniques, designs, and entrées into patronage networks were passed between family members and brethren, explaining some similarities between the work of Quaker potters in North Carolina and elsewhere. During the first half of the nineteenth century, as slave-owning practices caused many Quakers to relocate, several potters left North Carolina and settled in the Midwest. Although opposition to slavery had extended the Quaker pottery tradition west, oral and written accounts indicate that the demand for utilitarian pottery grew during and immediately after the Civil War, reigniting the tradition in North Carolina, where Quaker potters found a market for their wares well into the early twentieth century.

Stephen B. Weeks, Southern Quakers and Slavery: A Study in Institutional History (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1896), p. 3.

George Fox, an Autobiography, edited by Rufus M. Jones (Philadelphia: Ferris and Leach, 1904), p. 125.

Weeks, Southern Quakers and Slavery, pp. 4–5.

Harrold E. Gillingham, “Pottery, China, and Glass Making in Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 54, no. 2 (1930): 98–102; Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), pp. 62–64.

The Old Discipline, Nineteenth-Century Friends’ Disciplines in America (Glenside, Pa.: Quaker Heritage Press, 1999), p. 21.

Ibid., p. 419.

Mary Dennis, Thomas Dennis and Some of His Descendants: Circa 1650–1979 (Dublin, Ind.: Print Press, 1979), pp. 1–2.

Hannah Benner Roach, “Philadelphia Business Directory, 1690,” in Colonial Philadelphians (Philadelphia: Genealogical Society of Philadelphia, 1999), pp. 42–43.

Deed Book S, p. 387, Chester County Recorder of Deeds, West Chester, Pa.

William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 6 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1978), 1:536.

Will of Thomas Dennis II, written June 24, 1774, and proven in February 1775, Guilford County Wills, North Carolina State Archives (hereafter cited NCSA), Raleigh.

“Landgrant Entry No. 1560,” NCSA. The land was described as “Containing three hundred Acres laying in the County aforesaid on bouth sides the Trading road and west side of Pole cat adjoining Joseph Hills Entry running for compliment, Including the Improvement of Thomas Dennis.”

Thomas III appears in the Randolph County Tax List, 1779, NCSA; Deed Book 3, State Land Grant no. 319, p. 52, Randolph County Register of Deeds (hereafter cited RCRD), Asheboro, N.C.

Will of Thomas Dennis III, written November 11, 1795, and proven August 1803, NCSA. William Dennis had four siblings: Joseph, Sarah, Anne, and Elizabeth.

Dennis, Thomas Dennis and Some of His Descendants, p. 8.

Deed Book 7, p. 115, RCRD. William was issued by state land grant 60 acres in 1800 for a claim entered in 1799 (Deed Book 9, p. 447, RCRD).

Will of Thomas Dennis III.

Deed Book 13, p. 8, RCRD. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:741.

“Minutes of the N.C. Manumission Society, 1816–1834,” edited by H. M. Wagstaff, in The James Sprunt Historical Studies Nos. 1–2 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1934), p. 22. William’s opposition to slavery may have prompted his move to Indiana in 1832.

Randolph County Original Apprentice Bonds and Records 1806–1829, NCSA.

Mary Mendenhall Hobbs, “Old Jamestown,” p. 17, typed manuscript, Friends Historical Collection (hereafter cited FHC), Guilford College. Hobbs states that Richard Mendenhall was born on September 13, 1778, and at age fourteen was sent to Chester County, Pennsylvania, to learn the potter’s trade. Deep River Monthly Meeting minutes indicate that Richard was granted his certificate to Bradford Monthly Meeting, Chester County, on August 4, 1794 (Hinshaw Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:827). Based on that entry he would have been fifteen years old at the time of his departure.

Deed Book D, p. 493, Old Gloucester County Court House, Woodbury, N.J. Patents and Deeds and Other Early Records of New Jersey 1664–1703, edited by William Nelson (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1976), p. 432. Roach, “Philadelphia Business Directory,” pp. 42–43. Thomas’s Philadelphia lot was approximately 900 feet southeast of William Crews’s pottery, although no records of interaction between those men have been found. Beth A. Bower, “The Pottery-Making Trade in Colonial Philadelphia: The Growth of an Early Urban Industry,” in Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, 1626–1850, edited by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1985), pp. 267–68; Roach, “Philadelphia Business Directory,” p. 46.

Minutes of the Marlborough Monthly Meeting, pp. 133, 143, FHC.

J. A. Blair, Reminiscences of Randolph County (1890; repr., Asheboro, N.C.: Randolph County Historical Society, 1968), p. 50.

William Dennis owned 480 acres in 1815, according to 1815 Tax List of Randolph County, North Carolina, edited by Winford Calvin Hinshaw (Raleigh, N.C.: WPG Genealogical Publication, 1957), p. 29. Five years later he is listed as owning 330 acres and two lots in New Salem in 1820 Tax List of Randolph County, North Carolina, edited by Barbara N. Grigg and Carolyn N. Hager (Asheboro, N.C.: Randolph County Genealogical Society, 1978), p. 1; Deed Book 16, p. 39 and Deed Book 19, p. 194, RCRD. The William Dennis House remains standing today and is referred to as the Jarrell-Hayes House (Lowell McKay Whatley Jr., Architectural History of Randolph County, N.C. [Durham, N.C.: City of Asheboro, 1985], p. 114).

Deed Book 19, p. 90, RCRD.

Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:759.

Monthly Meeting Records, Springfield Monthly Meeting, First Friends Meeting Library, Richmond, Ind.

Deed Book 12, p. 317, RCRD. One hundred fourteen acres of this tract came from the northern part of the property granted by the state of North Carolina to Thomas’s great-aunt, Rachel Dennis (widow of Edward), and her sons.

Birth, Death, and Marriage Records, Centre Monthly Meeting, p. 136, FHC.

History of Wayne County, Indiana, 2 vols. (Chicago: Interstate Publishing, 1884), 2:447.

Deed Book 14, p. 140, RCRD.

History of Wayne County, Indiana, 2:447.

Dennis, Thomas Dennis and Some of His Descendants, p. 14.

Andrew W. Young, History of Wayne County, Indiana (Cincinnati, Ind.: Robert Clarke and Co., 1872), pp. 375, 420. See also John T. Plummer, A Directory to the City of Richmond (Richmond, Ind.: R. O. Dormer and W. R. Holloway, 1857). Another former resident of Guilford County, Amor Hiatt, established a pottery near Milton, which was also in Wayne County, Indiana. (Luther M. Feeger, “Our History Scrapbook: Amor Hiatt Potter Shop Recalled in Early History about Milton,” Palladium Item [Richmond, Ind.], January 30, 1956.)

Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, NCSA. Thomas Dennis “first located near Dublin, but the wolves being so troublesome he went to Perry Township, near Economy, where he wintered, purchasing during that time ninety acres on Green’s Fork, one mile south of Washington, where he resided until Oct. 1, 1831.” Young, History of Wayne County, Indiana, p. 447. If that account is accurate, he would not have been near either pottery long enough for employment.

Thomas acquired an adjoining 80 acres. He farmed this property and became tax assessor of a 108-square-mile area in Wayne County prior to his death. Young, History of Wayne County, Indiana, pp. 447–48.

Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to about 1820, 4th ed., 2 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Clearfield Publishing, 2001), 1:214. United States Federal Census, 1800, Randolph County, N.C.

James H. Craig, The Arts and Crafts in North Carolina 1699–1840 (Winston-Salem, N.C.: Old Salem, Inc., 1965), pp. 90–91.

Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, NCSA.

A Narrative of Some of the Proceedings of the North Carolina Yearly Meeting on the Subject of Slavery within Its Limits (Greensboro, N.C.: Swaim and Sherwood, 1848), p. 23.

United States Federal Census, 1830, Wayne County, Ind.

United States Federal Census, 1840, 1850, Wayne County, Ind. Elliana is recorded as being thirteen years old.

Ebenezer Tucker, History of Randolph County, Indiana (Chicago: A. L. Kingman, 1882), p. 134.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Randolph County, Ind.

Real Estate Records: Appraisement List and Transfers of Real Estate, June 1, 1859, to June 1, 1864, Randolph County Recorder of Deeds, Winchester, Indiana. United States Federal Census, 1860, Randolph County, Ind.

Deed Book 19, p. 13, Randolph County Recorder of Deeds, Winchester, Ind.

United States Federal Census, 1870, Van Buren County, Mich.

Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, p. 214.

Orange County Apprentice Bonds and Records, 1780–1905, NCSA.

Craig, Arts and Crafts in North Carolina, pp. 90–91.

Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:691, 771.

Grigg and Hager, eds., 1820 Tax List of Randolph County, p. 4.

Deed Book 20, p. 235, RCRD.

Craig, Arts and Crafts in North Carolina, p. 93. The date of birth on the indenture could be wrong, since the document was originally drawn up for another brother, William Watkins. William’s name was crossed out and Joseph’s name added with no change made to the birth dates. Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, NCSA.

Randolph County, N.C., Marriage Bonds, p. 179, RCRD.

Deed Book 17, p. 299, RCRD.

Deed Book 22, p. 343, RCRD.

Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:691; Deed Book 2B-27, pp. 89–90, Guilford County Register of Deeds (hereafter cited GCRD), Greensboro, N.C.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Guilford County, N.C.

United States Federal Census, 1860, Guilford County, N.C.

John B. Crenshaw Papers, C12, Digital Collections, FHC, www.guilford.edu/fhc.

Sarah Ester Ross and Mrs. Lewis Grigg, Levin Ross and Thomas McCulloch with Related Families (Asheboro, N.C.: Ross, 1973), p. 96.

Deed Book 3, p. 411, Rowan County Register of Deeds (hereafter cited RowRD), Salisbury, N.C.

Deed Book 5, p. 263, RowRD.

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), pp. 38–39.

Deed Book 8, p. 435, RCRD. See also Randolph County “Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions,” vol. 6, p. 200: “Ordered that Peter Dicks have leave to build a water grist mill on Deep River on his own land.”

Randolph County Apprentice Bonds, NCSA.

Blair, Reminiscences of Randolph County, p. 50; Laws of North Carolina 1818, chap. 91, microfiche, State Library of North Carolina, Raleigh.

Deed Book 19, p. 90, RCRD.

Will Book 8, pp. 26–27, microfiche, Asheboro Public Library, Asheboro, N.C. (hereafter cited APL).

United States Federal Census, 1850, 1860, Guilford County, N.C.; R. R. Ross, “History of the Highway from Climax to Trinity,” unpublished ms., 1927, APL.

Interview with Nettie Dicks Lamb, August 24, 1990.

Interview with Franklin and Ruby Cox, October 31, 1989; interview with Ann S. Turner, November 25, 2007.

Will Book 16, p. 299, microfiche, APL. Cornelius died three years later.

United States Federal Census, 1880, 1900, New Market Township, Randolph County, N.C. Nathan was probably working in his father’s shop from the 1870s to the mid-1880s. He married Rodemia E. Millikan on November 25, 1877, but the 1880 census lists him as a widower. He married Nancy M. Chriscoe on July 14, 1880. See Ross and Grigg, Levin Ross and Thomas McCulloch with Related Families, p. 105.

United States Federal Census, 1910, Morehead Township, Guilford County, N.C.

Interview with Iro Trueblood Swaim, October 6, 1991. Swaim recalled that her family owned “pie dishes” made by Nathan Dicks.

Interview with Eleanor Hartley, 1980.

Young, History of Wayne County, Indiana, p. 325. Beeson served as town marshal in 1826. See John Plummer, “Reminiscences of Richmond History,” in Plummer, A Directory to the City of Richmond.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Randolph County, Ind.

George J. Richman, History of Hancock County, Indiana: Its People, Industries and Institutions (Greenfield, Ind.: W. Mitchell Printing Co., 1916), p. 492.

Ibid., pp. 104–5.

United States Federal Census, 1860, Hancock County, Ind.

“The house and lot, consisting of two acres, were bought of Isaac Beeson for the sum of four hundred and fifty dollars. The house, which was a hewed-log building, was used for several years previous as a ‘potter’s shop,’ and was known by that name for nearly nine years, when a committee, composed of Jonathan Jessup, John Hunt, Lewis G. Rule and Elihu Coffin, were appointed to solicit money and material for a new church building”; Richman, History of Hancock County, p. 509.

Sarah Myrtle Osborne and Theodore Edison Perkins, Hocketts on the Move: The Hoggatt/Hockett Family in America (Greensboro, N.C.: S. M. Osborne, 1982), pp. 19–21.

Ibid., p. 23.

Ibid., p. 246.

In 1990 the bottle still held an aroma of coffee. Interviews with Margaret Fields Coltrane, March 1990, and Jane Coltrane Norwood, February 24, 2007.

Osborne and Perkins, Hocketts on the Move, p. 210.

Coltrane interview, 1990; Norwood interview, 2007.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Guilford County, N.C.

United States Federal Census, 1850, 1860, Guilford County, N.C. Watkins lived at residence number 728 and is listed as a miller.

United States Federal Census, 1860, Guilford County, N.C. Interview with Winford Calvin Hinshaw, 1987.

Nancy M. Hockett and Cyrus Elwood Hockett to Himelius Hockett, November 4, 1863, transcribed and filed in Hockett Papers, FHC.

John B. Crenshaw Papers, C12, FHC. William Osborn also signed the petition to Jefferson Davis.

Ibid. Other account book pages used by Branson suggest that he was a merchant. The 1850 census lists him as a farmer and the owner of real estate valued at $5,000, a significant sum for the time. United States Federal Census, 1850, Guilford County, N.C.

John B. Crenshaw Papers, F11, FHC.

Interview with Carrie Hockett Cox, March 5, 1990. Cox described David Hockett visiting her grandfather Himelius: “I remember David. His wife died and he lived there by himself for a long time and he wore long whiskers, and he’d come over here once in awhile to see my grandfather . . . I just can remember him; I was a little girl.” She said her parents inherited the home place from Himelius and looked after him when he was older. According to Cox, her mother “would crawl [into the kiln] . . . and get the eggs.”

Interview with Winford Calvin Hinshaw, March 29, 1992. According to Hinshaw, Himelius and Milton Hockett made salt-glazed stoneware after 1860; it is known that Himelius’s son Cyrus Elwood Hockett (1860–1938) also made salt-glazed stoneware.

Interview with Worth Everett Cox, March 5, 1990. Cox recalled the David Hockett pottery building and kiln:

Now there was another crockery over there, the other side of the farm I lived on . . . they made crockery and I think and I wouldn’t say, but I think the old building is there yet. . . . They cured it they had a rock wall that they cured it in, right across the branch. I believe they called that the David Hockett Place.

Interview with Butch Thompson, September 2, 1991. According to Thompson, David Hockett fired brick in his kiln about 1885 and used them to build the chimney of the latter’s house.

Interview with Roy Coltrane, April 8, 1990.

Interview with Sarah Haworth, September 13, 1990. According to Haworth, her mother took a piece of Mahlon’s pottery to the one-hundredth-anniversary celebration of the Springfield Monthly Meeting:

[In] 1890, they celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the establishment of Springfield Monthly Meeting and my grandmother had a piece of Mahlon Hocketts pottery and she tried to get some of the folks to bring some, but everybody—it was after the war, you know—and the Quakers were poor and didn’t have slaves or anything, and they were all using theirs and nobody brought any, so she was the only one who had a piece of Mahlon Hockett’s pottery there.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Guilford County, N.C.

United States Federal Census, 1860, Randolph County, N.C.

United States Federal Census, 1880, Rush County, Ind.

Deed Book 11, p. 45, GCRD.

Hobbs, “Old Jamestown,” p. 17.

Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:827.

Arthur Edwin James, The Potters and Potteries of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1978), pp. 107–9.

William Mendenhall and Edward Mendenhall, History, Correspondence, and Pedigrees of the Mendenhalls in England and the United States (Cincinnati, Ohio: Moore, Wilstach, and Baldwin, 1864), p. 35. Jesse Kersey started having health problems after Richard Mendenhall’s arrival. His brother-in-law, Dr. Jesse Coates, prescribed a mixture of laudanum and brandy, which further debilitated Kersey. James, Potters and Potteries of Chester County, p. 109.

Vickers married Richard and Jonathan’s cousin Jemima Mendenhall. Her son Ziba was a potter who subsequently married Jesse Kersey’s daughter, Lydia. Mendenhall and Mendenhall, History, Correspondence and Pedigrees of the Mendenhalls, p. 35; James, Potters and Potteries of Chester County, pp. 166–71. Richard Mendenhall’s brother, Stephen, died while apprenticing as a tanner; Mendenhall and Mendenhall, History, Correspondence and Pedigrees of the Mendenhalls, p. 35. Richard completed his apprenticeship as a tanner. In July 1800 he received a certificate of removal from York Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania to Deep River Meeting. He had lived in Pennsylvania for six years. Mendenhall married Mary Pegg in Guilford County, North Carolina, on February 3, 1812. Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, 1:828.