Slipware bowls, North Carolina. Lead-glazed earthenware. Left: Bethabara or Salem, 1770–1790. D. 6". (Private collection.) Right: recovered at the site of the gunsmith’s shop at Bethabara, 1787–1789. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

Slipware bowl fragment recovered at Gottlob Krause’s pottery site, Bethabara, North Carolina, 1790–1800. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Historic Bethabara Park.)

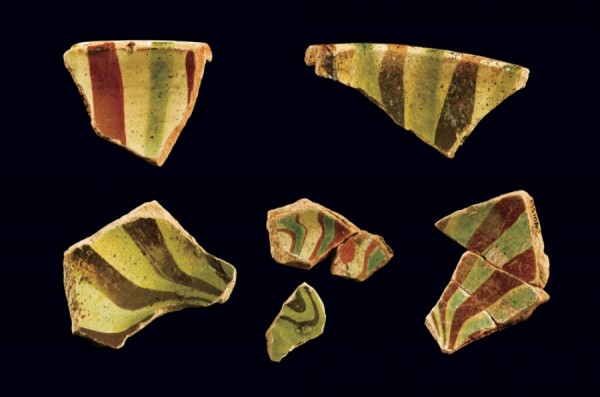

Slipware bowl fragments, recovered at the Mount Shepherd pottery site, Randolph County, North Carolina, 1793–1800. (Courtesy, Mount Shepherd Collection, Mount Shepherd Retreat Center.) These marbleized fragments are nearly identical to those excavated at Bethabara.

Dish, Netherlands, late-seventeenth century. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Chipstone Foundation.) This example shows the use of slip with a technique similar to that used at the William Rogers pottery in Yorktown, Virginia.

Fragmentary dish recovered at the William Rogers pottery site, Yorktown, Virginia, 1720–1745. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. approx. 13". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Colonial National Historical Park, Yorktown Collection.) Among several large fragments recovered from the Rogers site is this partially reassembled dish. The technique used to create the marbled pattern is similar to that used by the North Carolina Moravian potters.

The deep-sided bowls are thrown on the wheel in a white earthenware and allowed to dry to a leather-hard state.

White slip is poured into the interior of a leather-hard bowl and then poured off, leaving a wet coating on the surface.

The bowl is tilted slightly and immediately lines of red slip are dropped onto the top of the rim and allowed to flow freely downward.

A second series of brown slip lines are placed between the red slip lines.

All of the red and brown lines have been dropped. The white-colored ground slip and the slip lines are still quite wet and fluid.

The bowl is tipped and rotated to swirl the slip lines at the bottom of the bowl. This must be done before the slips become too dry to flow easily.

When the marbling effect is complete, the bowl is allowed to dry thoroughly before the bisque firing.

A group of marbled bowls in the wet state surrounds the archaeological specimen recovered from Bethabara illustrated in fig. 1. There is inherent variation in all these examples, including the clockwise and counterclockwise swirl of the slip lines. This technique is a quick but effective means of creating repetitive yet individualized decoration.

One of the most distinctive decorated vessel types associated with eighteenth-century Moravian pottery is a small, deep-sided bowl with marbleized decoration made using two or more colors of contrasting slips. The best surviving prototype is a nearly complete example excavated from the gunsmith’s site in the Bethabara community (fig. 1). The shape of the thrown form is unlike English examples of the period and must relate to a Germanic bowl type. Fragments of these slip-decorated bowls have been excavated from the pottery sites in both Bethabara and Salem (fig. 2).[1] Most important, perhaps, is the discovery of fragments of nearly identical bowls at the Mount Shepherd pottery of Philip Jacob Meyer, a former apprentice of Gottfried Aust (fig. 3).[2]

The appearance of these slip-decorated bowls stands in pronounced contrast to the carefully trailed floral designs characteristic of the Moravian decorative oeuvre. The deep-sided bowls are distinguished by the use of alternating bands of colored slip poured over a white slip that run downward from the lip of the rim and flow into the bottom. The bowl is then moved in a swirling motion to create a marbled pattern from the free-flowing slips. The use of two or more colors of slip to simulate marble patterning has its origins in antiquity, and British and European potters made great use of the technique in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[3] European parallels for creating a marbled slipware pattern abound, and the decorative style exemplified by the Moravian bowl has definite Germanic/Netherlandish traits (fig. 4). Yet a surprising American precedent for this pattern is found at the William Rogers kiln site at Yorktown, Virginia (fig. 5).

The Rogers pottery produced earthenware and stoneware in the English style from about 1720 to about 1745. Some of the artifacts found there, including stove tiles and, more specifically, Germanic-style slipwares, suggest that Rogers employed potters with that training. No historical evidence has been found regarding the identity or nationality of Rogers’s potters, however, and the making of Germanic-style stove tiles and marbled slipware in Yorktown some twenty years or more before the settlement of Bethabara remains a mystery. It does, however, underscore the popularity of decorative marbling in utilitarian slipware.

The recent reevaluation of Moravian slipware decoration has revealed a connection between the floral motifs used and the religious sect’s cosmology.[4] In fact, new research suggests that the slip-trailed techniques used by Moravian potters might have been restricted to plates and dish forms made primarily for display rather than daily use. The marbled bowl, however, is radically different from such carefully drawn floral chargers, as are the colors and clays used to form it.

The symbolic significance of the marbled decoration to the Moravians is unknown, though the exuberantly styled bowls probably served a utilitarian function. Marbelized fragments excavated at Bethabara indicate that Gottfried Aust might have been responsible for introducing the technique into the Moravian workshops. Comparable fragments found in Salem and Bethabara demonstrate that he and/or his apprentices were also making these bowls there from about 1771 into the early 1800s. In addition, Philip Jacob Meyer, a former Aust apprentice who worked at Salem from 1786 through 1788, used an identical technique at his pottery, in Randolph County, North Carolina (fig. 3).

Previous explanations of the process utilized to decorate these bowls have suggested that the slip lines were “combed” by dragging bristles or a stylus through them, a description that is both inaccurate and misleading.[5] In fact, the marbling is achieved solely with the potter’s skill and the effects of gravity, as will be demonstrated by our re-creation.

The bowls from Bethabara, Salem, and Mount Shepherd are steep-sided, thrown on the wheel in a buff-colored clay with a slightly rounded rim and a flat bottom, having been cut directly from the wheel. The bowls would have been thrown in batches, perhaps several dozen at a sitting, and allowed to dry to a leather-hard state (fig. 6).

Although the marbled pattern looks random, in fact it requires carefully prepared batches of slip and a measure of control by the potter. The essential element of creating marbled decoration is the viscosity of the various colored slips—too thin and the mixtures are uncontrollable, too thick and the slips will not flow.

The interior of the leather-hard bowl is first coated with a fine white ground slip (fig. 7). In addition to the white ground, slips of two colors were normally used on the Moravian examples: a reddish brown and a green made from copper oxides. For demonstration purposes, a red slip and a dark brown slip were used for this article.

While the ground slip coating is very wet, colored slips are dropped from the rim and allowed to flow naturally to the bottom of the bowl. The first color is applied around the perimeter of the rim at intervals (fig. 8), then the second color is dropped between the previously applied lines (fig. 9). The application of the slip lines is necessarily a quick procedure, since gravity is utilized to create the lines, not any action by the potter.

The bottom of the bowl is now saturated with three colors of slip: the white ground and the brown and red lines (fig. 10). At this point, the potter retakes control of the patterning by rotating and tipping the bowl to permit the slips to swirl around the bottom of the bowl (fig. 11). The swirling process takes place in a matter of seconds as the slips begin to dry (fig. 12). The two intact antique bowls illustrated in figure 1 as well as the replications show that the potter could make the swirling go in either a clockwise or a counterclockwise direction (fig. 13).

Once the slip decorating is completed, the bowls are air-dried, bisque-fired, and then covered in a lead glaze for the final gloss-firing.

It is hoped that the demonstration of the marbled slip decorating technique used by the Moravian potters will help future researchers recognize and better understand new examples that might arise from archaeological contexts or in the antiques market. Thus far, this technique—in the Moravian context—has been found only on very specific bowl forms and used only on the interior surface, although it also would have worked well on flat plates and dishes, as exemplified on the earlier examples made at the William Rogers pottery in Yorktown. Why the marbling technique was limited to the Moravian bowl forms remains an unanswered question.

Also unknown is how these bowls functioned in the Moravian community. Were they simply decorative utilitarian vessels? Perhaps they were intended for very specific kinds of foods, such as desserts or puddings. Whatever the case, a great deal of preparation went into creating such graphically appealing products.

Stanley South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia: Excavating Eighteenth-Century Bethabara and Moravian Pottery (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999), pp. 226–34; John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972), pp. 220–23.

L. McKay Whatley, “The Mount Shepherd Pottery: Correlating Archaeology and History,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 6, no. 1 (May 1980): 21–57.

Michelle Erickson and Robert Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles: Early English Slipware Technology,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 94–114; Mary Wondrausch, Mary Wondrausch on Slipware: A Potter’s Approach (London: A&C Black, 1986); Erickson and Hunter, “Dots, Dashes, and Squiggles,” pp. 107–13.

Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter and Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 2–67.

See South, Historical Archaeology in Wachovia, p. 233; Bivins, Moravian Potters in North Carolina, p. 221; and Whatley, “Mount Shepherd Pottery,” p. 28.