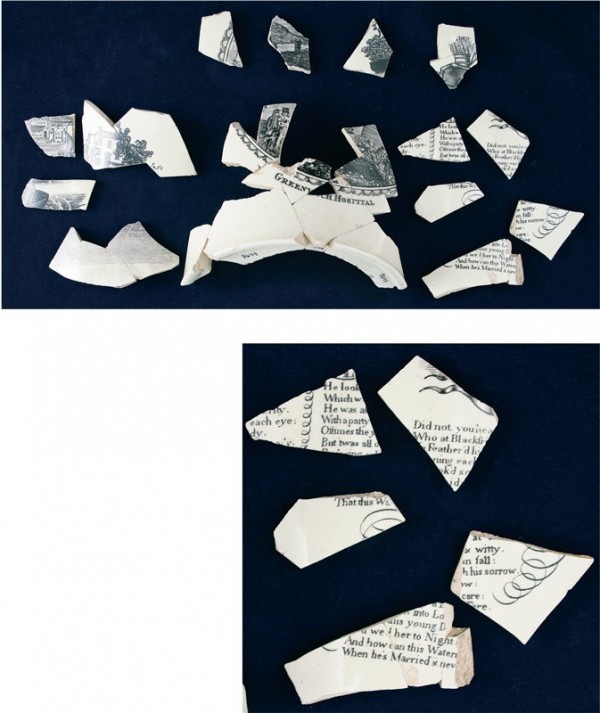

Jug fragments, probably Liverpool, England, 1792–1800. Creamware. H. of base sherd 3". (Photo, Carl Steen.) Over its glaze the vessel is decorated with a black transfer-printed motif labeled “GREENWICH HOSPITAL” on one side and, on the other, the lyrics from a musical written in 1774 by Charles Dibdin.

Thomas Nicholson, William Walker, and John Walker, Greenwich Hospital, London, England, 1792. Etching and engraving. 5 3/4" x 7 3/4". (Courtesy, National Maritime Museum, London.) This print is the source for the transfer-printed image on the jug fragments illustrated in fig. 1, and thus dates the vessel to 1792 or later.

Mug, probably Liverpool, England, 1792–1800. Creamware. H. 6 1/8". (Courtesy, National Maritime Museum, London.) The print on this vessel has been recorded on commemorative mugs and jugs, and proved helpful in the identification of the fragmented jug from Fort Johnson. The transfer-printed motif of London’s Greenwich Hospital is based on the engraving illustrated in fig. 2.

In excavations at Fort Johnson, on Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, sherds of a creamware pitcher with a black transfer-printed overglaze decoration were found in a midden deposit dating to the late eighteenth–early nineteenth century. Many of the prints used on such vessels were commemorative, celebrating heroic figures and great events, such as Lord Nelson and the British victory at Trafalgar. Creamware vessels like this are not unfamiliar finds in deposits dating between the 1780s and 1820s, but this is the most complete example found at Fort Johnson, and is one of the few archaeological examples whose commemorative scene and a seemingly unrelated verse can be identified.

Without the Internet, and the Google search engine specifically, this identification likely would not have been made. Many pieces survive, but they did not form a cohesive picture. Two of the first sherds found were marked “. . . ICH HOSPI . . .” (fig. 1), and a Google search revealed that Greenwich Hospital was founded in 1694 as the Royal Naval Hospital and served that purpose until 1869.[1] Numerous hospital images were also available online, and a mug with the identical print helped prove that all the sherds came from the same vessel (figs. 2, 3).

More frustrating were the sherds with writing on them, as all had to be retrieved from the collection and crossmended. In the absence of a visible title or full sentence, the phrase “And wed her to Night” seemed unique enough to qualify for a Google search, which indicated it is a portion of a song composed by an Englishman named Charles Dibdin (b. ca. 1745).[2] The son of a parish clerk in Southampton, Dibdin chose music over the priesthood (against his parents’ wishes) and moved to London in 1760, at age fifteen. He became a singer and actor, and within two years he had written his first production. Dibdin continued to write music for his own works as well as for such theatrical luminaries as David Garrick, a highly influential English actor, playwright, and producer. Dibdin later became famous for his war songs, which were financed by Lord Pitt and the Royal Navy and used to stir national spirit against France at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In 1774 Dibdin wrote the musical The Waterman, from which our song was taken, the title referring to the men who transported people along and across Britain’s rivers on small boats, or wherries.[3] “And wed her to Night” turns out not to be a dark metaphor but simply a phrase whose meaning—“And wed her tonight”—was clouded by the syntax of another era.

The message conveyed by this artifact is multifaceted. A jug commemorating a naval hospital and watermen in general is certainly appropriate. When not defending Charleston against military enemies, Fort Johnson and its hospital served as a quarantine facility and the wharf a public landing for the people of James Island, many of whom in the early nineteenth century traveled to the city in boats manned by watermen.

Yet in the early nineteenth century tension was high among the British, French, and Americans, and in 1807–1808 these tensions led to federal renovations of the fortifications at Fort Johnson that sealed the midden deposit in which the sherds were found. London’s borough of Greenwich is home to more than just the naval hospital, however; it is also the site of the naval observatory and has numerous military connections. In that sense, it is a bit odd that a vessel commemorating the royal navy would be found at the place built to defend against it.

One of the interesting and enjoyable things about archaeology are the little-traveled paths that one encounters. To go from a creamware sherd in the sand to a night at the theater in 1774 London is a long journey through time and space. The technology that makes this possible has been available for only a short while—and one can only imagine what is in store for future researchers.

Carl Steen, President, Diachronic Research Foundation, P. O. Box 50394, Columbia, South Carolina 29250

carl.steen@gmail.com

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenwich_Hospital_%28London%29#Greenwich_Hospital.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Dibdin. Dibdin reputedly wrote more than fourteen hundred songs, thirty dramatic plays, and three novels. Today there is a memorial to Dibdin, complete with statue, at the Royal Hospital in Greenwich.

Joseph Woodfall Ebsworth, ed., The Bagford Ballards: Illustrating the Last Years of the Stuarts, Volume 1 (Hertford: Stephen Austin and Sons, 1878), p. 254. Dibdin’s full verse of “The Waterman’s Delight,” from act 1 of The Waterman (1774), was likely influenced by a ballad entitled “The Waterman’s Delight; or the Fair Maid,” written a century earlier.