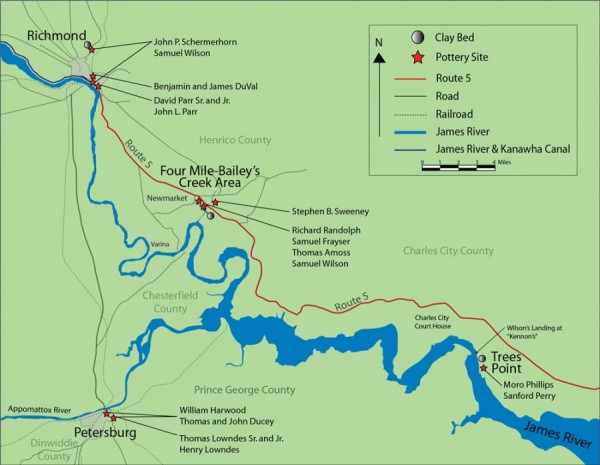

Map of Richmond–Petersburg area of Virginia, showing the locations of known and suspected stoneware potteries and clay beds. (Drawn by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

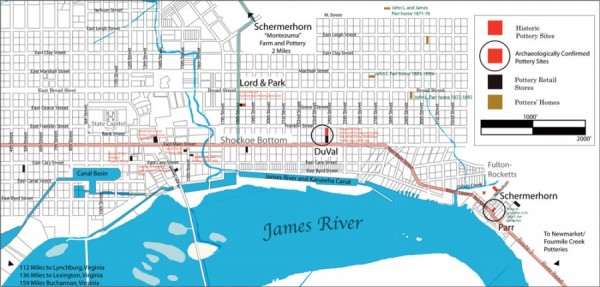

Map of Richmond, Virginia, showing nineteenth-century pottery sites and stoneware retail stores. (Drawn by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

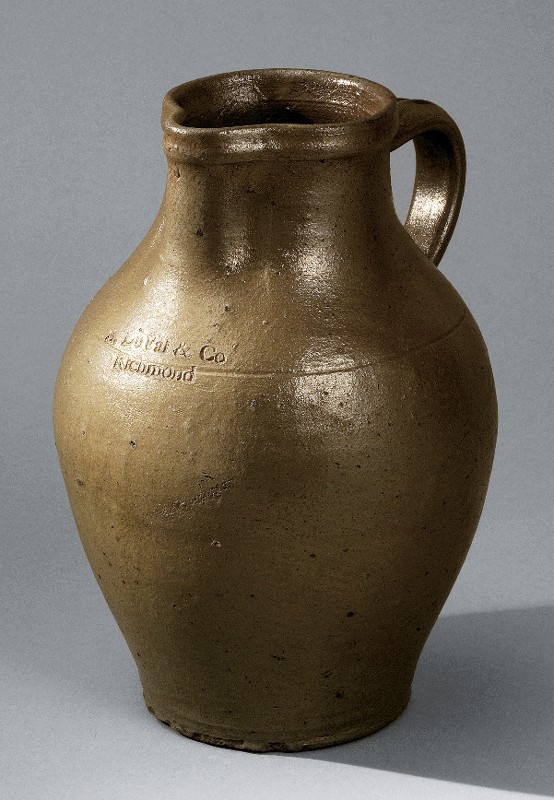

Pitcher, Benjamin DuVal & Co., Richmond, Virginia, 1811–1817. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Capacity: 1 gallon. Stamped mark: “B. DuVal & Co. / Richmond” (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Storage jar, Schermerhorn Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1837. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 3/8". Capacity: 4 gallons. Stamped mark: “RICHMOND FACTORY / Virga / J. P. SCHERMERHORN” (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Water or beer cooler, Schermerhorn Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1837. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 27 1/2". Capacity: 30 gallons. Incised marks: [on front] “John P. Schermerhorn & Co./, Makers” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) This massive cooler was recently discovered in an eastern Virginia estate and may have seen use in a local tavern or business. The form clearly relates to Albany stoneware, whereas the cobalt floral vines recall Baltimore decorative motifs. This is the only known vessel with Schermerhorn’s hand-incised signature.

Map showing location of two J. P. Schermerhorn pottery manufactories, one at Rocketts (1817–1837), the other adjacent to his residence at Montezuma (1828–1850), two miles north of Richmond on the Mechanicsville Turnpike. Reproduced from George B. Davis et al., The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War (1891–95; repr., New York: Gramercy Books, 1983), pl. xix, no. 1.

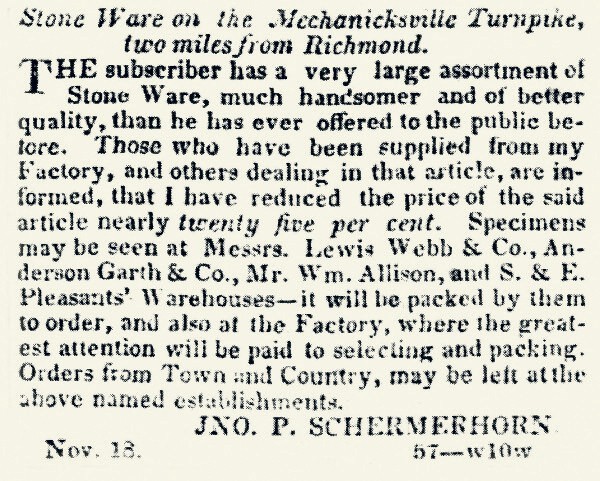

Advertisement identifying J. P. Schermerhorn’s “Mechanicksville Turnpike” stoneware factory. Richmond Enquirer, January 1, 1829, p. 4.

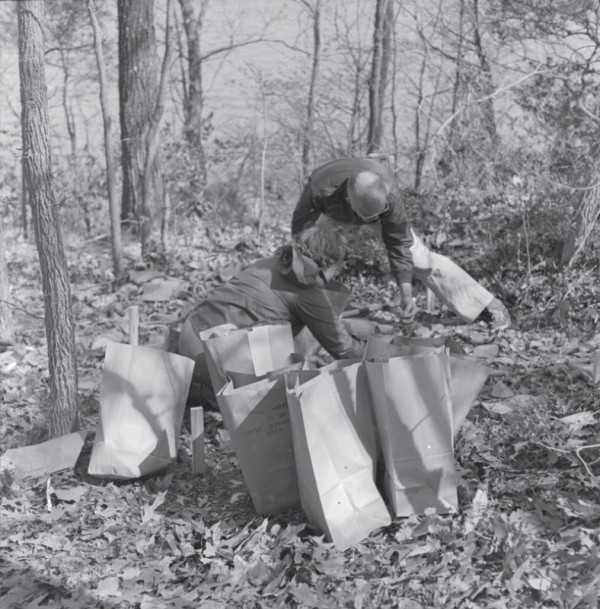

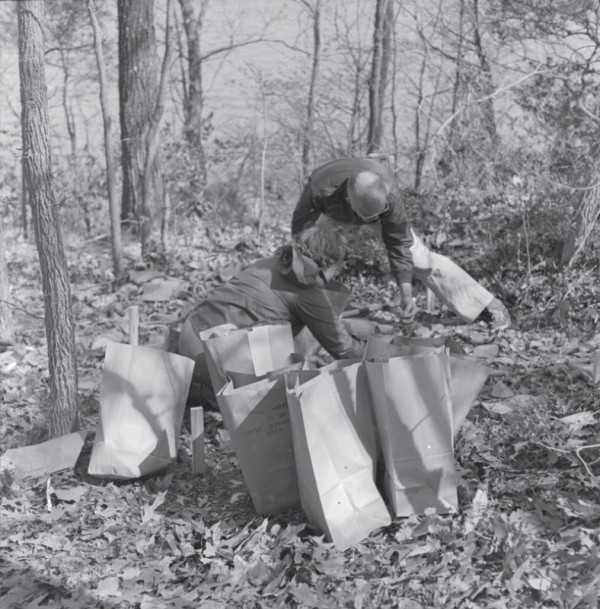

Archeological salvage work at Montezuma, the home and workplace of John P. Schermerhorn, 2010. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Oliver Mueller-Heubach records evidence and gathers artifacts from Schermerhorn’s pottery, established sometime after his purchase of the land in 1823. According to advertisements, the operation was up and running by 1828.

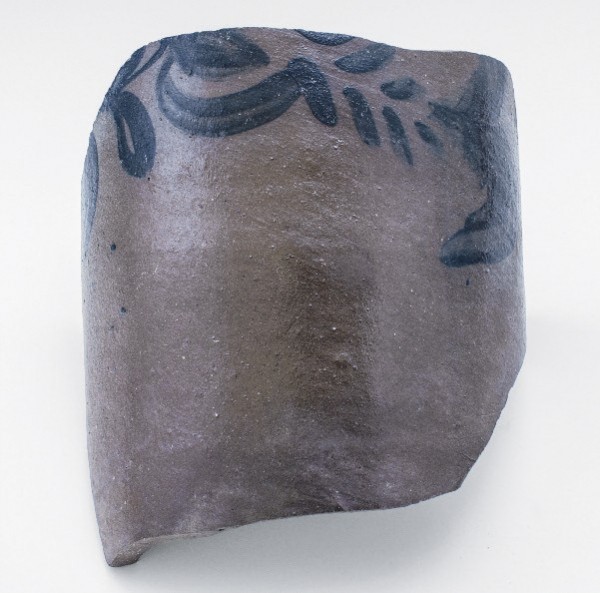

Stoneware fragments, attributed to John P. Schermerhorn, Henrico County, Virginia, 1828–1850. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments were found at Montezuma.

Churn, attributed to John P. Schermerhorn, Henrico County, Virginia, 1828–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 2 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to John P. Schermerhorn, Henrico County, Virginia, 1828–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. Inscribed, in brushed cobalt: “A. JACKSON” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The brushed-cobalt portrait of a bearded Andrew Jackson in military uniform wielding his sword in his right hand dominates the front of the vessel; on the reverse, above the inscription, is Jackson’s profile.

Reconstruction of the stamp used by Keesee & Parr. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

Jar, Keesee & Parr, Richmond, Virginia, 1860–1865. Salt-glazed stoneware, H. 14". Capacity: 3 gallons. Inscribed, in cobalt: “Keesee & Parr / Richmond / Va” (Courtesy, The Valentine; photo, Crocker Farm Auctions.)

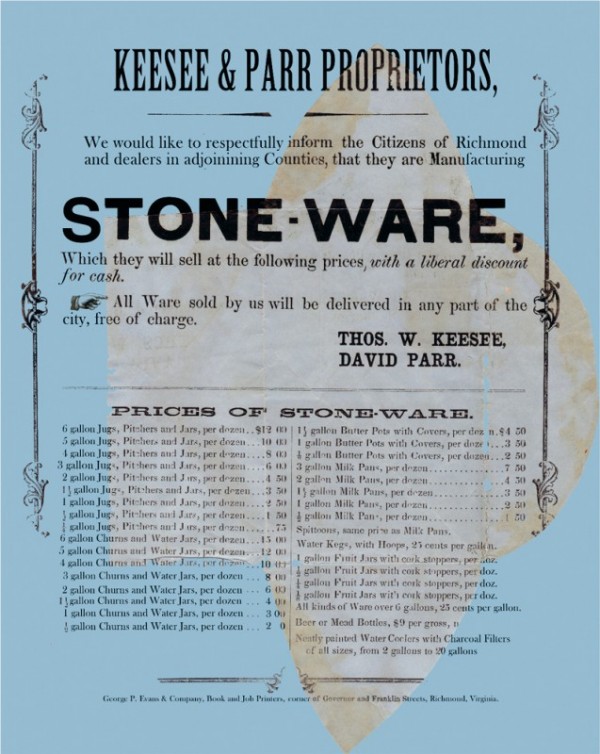

Digital restoration of Keesee & Parr handbill, 1858–1865. (Private collection.) This handbill, printed by George P. Evans and Co. in Richmond, Virginia, details the various forms offered by the business and the price of each. When found, the handbill had been cut and folded to create an envelope, a relic of Richmond’s wartime paper shortage. Two Jefferson Davis stamps were affixed to the outside. It is addressed to Franklin Davis, Loudon County, Virginia, sent by “D. Parr,” whose signature appears in the upper left edge of the envelope.

Stoneware fragments from the David Parr Pottery site with flower decoration typically sold under the Keesee & Parr name. (Courtesy, William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research.)

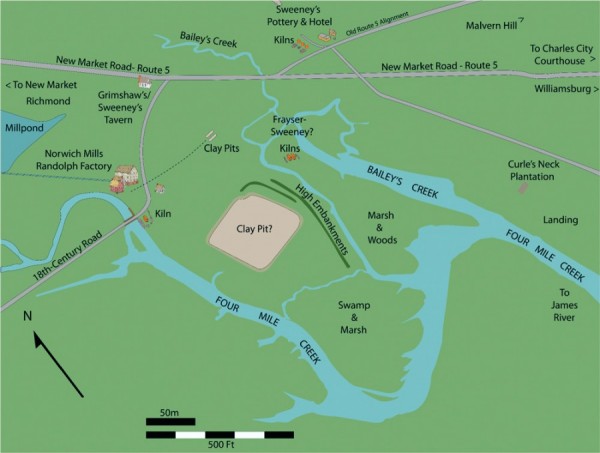

Map showing the Four Mile Creek/Bailey’s Creek area of southeastern Henrico County, Virginia. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

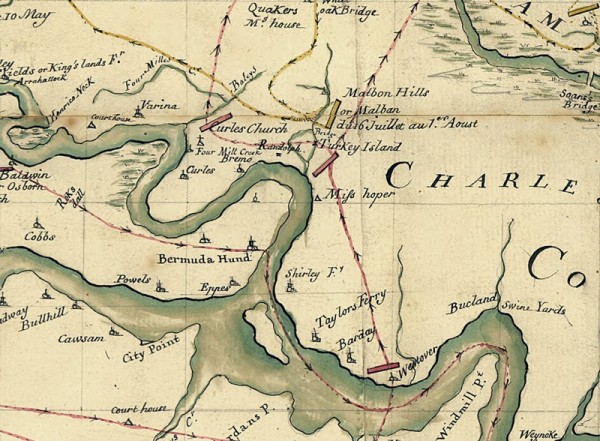

Detail, Campagne en Virginie du Major Général M’is de LaFayette: ou se trouvent les camps et marches, ainsy que ceux du Lieutenant Général Lord Cornwallis en 1781, by Major Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy, aide-de-camp of General LaFayette. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

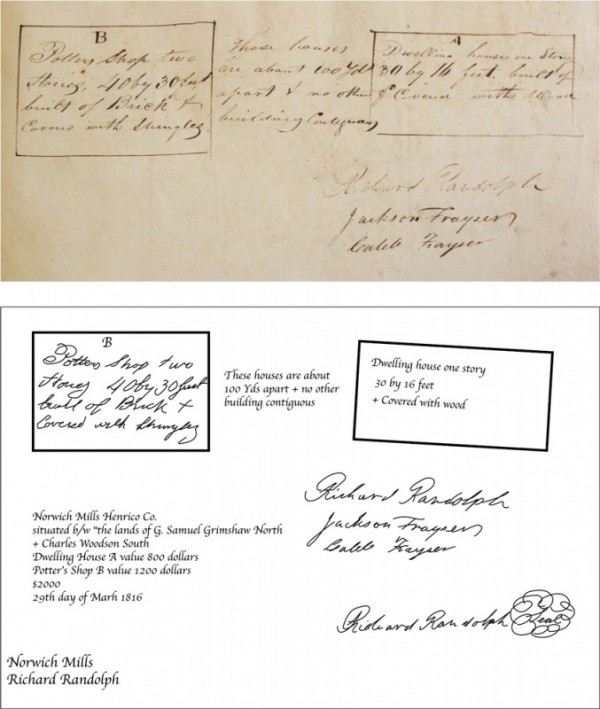

Top: Mutual Assurance Society sketches of insured buildings comprising David Ross’s Norwich Mills complex in 1816. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.) Bottom: Black-and-white schematic sketch of the insured buildings. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

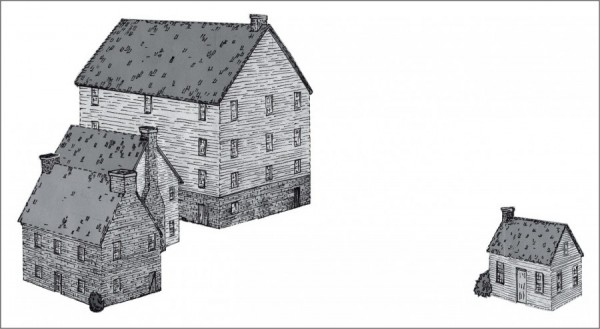

Hypothetical illustration of eighteenth-century Norwich Mills complex showing the buildings on site from the time of Ross’s 1809 transfer (reflecting those insured in 1806) to the evolution or conversion in 1816 of the site to a pottery manufactory (ca. 1812–1813) under Randolph’s ownership. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

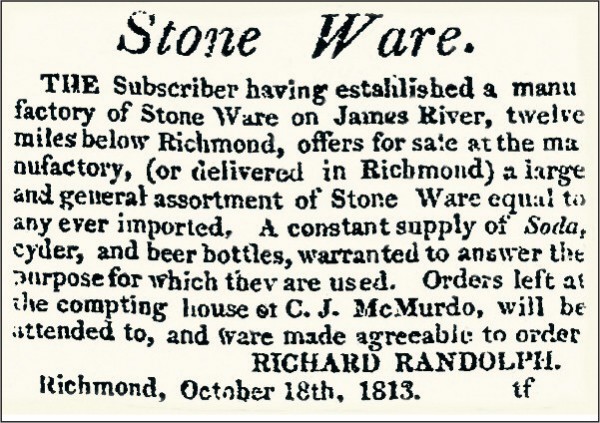

Advertisement for Randolph’s “Soda, cyder, and beer bottles” available for sale at C. J. McMurdo’s “compting house” in Richmond, October 18, 1813. Enquirer, Richmond, October 22, 1813, p. 3-4.

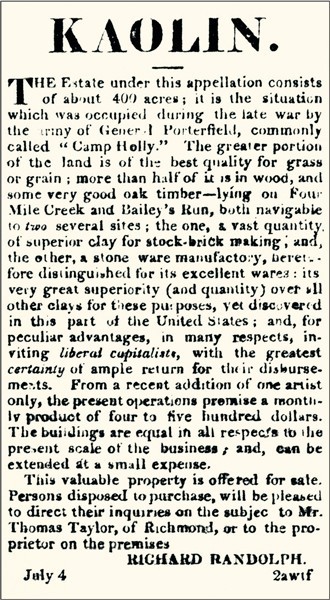

Advertisement for Richard Randolph’s Kaolin estate, July 4, 1817. Enquirer, Richmond, July 4, 1817.

Storage jar fragments, Richard Randolph Manufactory, Four Mile Creek, Henrico County, Virginia, 1813–ca. 1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. Impressed mark: “Richd Randolph / MANUFACTURER” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) No intact examples of stoneware with this mark are known.

Reconstruction of the Richard Randolph mark. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

Pottle, attributed to the Richard Randolph pottery, Henrico County, 1813–ca. 1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The identical lip-and-neck configuration has been found among archaeological collections at Monticello. Those pottles were ordered by Thomas Jefferson in 1814 to hold beer brewed by Peter Hemmings.

Illustration and cross-section of a sea kale pot based on fragments recovered from Monticello and now attributed to Thomas Amoss’s production at the former Randolph pottery on Four Mile Creek in southeastern Henrico County, Virginia. (Artwork by Tabitha Lavis.)

Kale-pot fragments, attributed to Thomas Amoss, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1822. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Department of Archaeology, Monticello; photo, Kurt Russ.) Note the cobalt slip decoration of dots and sea kale sprouts around the circumference and the top of the lid. The clay and the style of the cobalt slip application match Amoss’s production at Four Mile Creek.

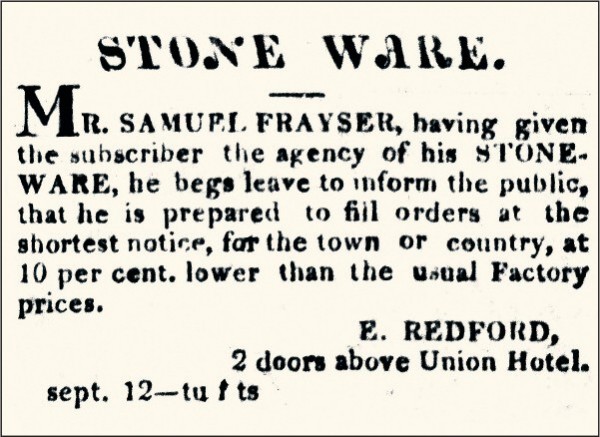

E. Redford advertisement for Frayser stoneware appearing in the Richmond Commercial Compiler, September 12, 1820, p. 3-5.

Vessels, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of tallest 15". The largest pitcher is dated 1836. (Private collections; photo, Kurt Russ.) The storage jar has a brushed-cobalt capacity mark, “4,” under one handle and a “K” beneath the other.

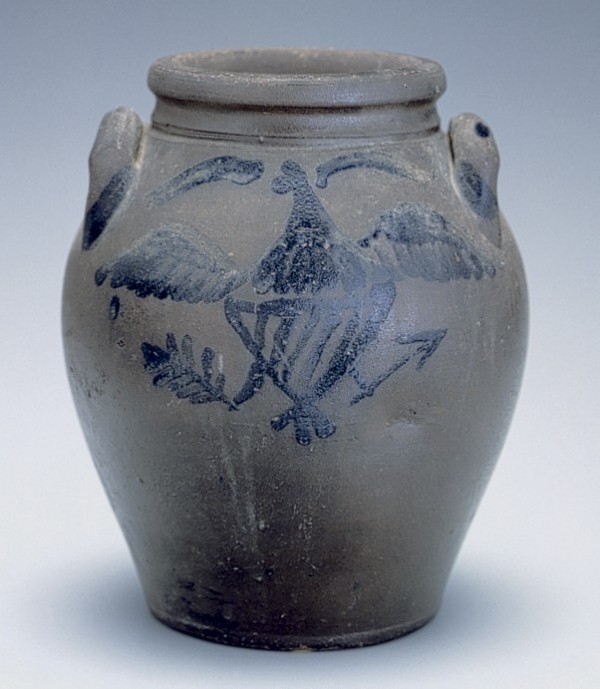

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This ovoid storage jar displays a similar eagle on the reverse, but that version has olive branches in both talons.

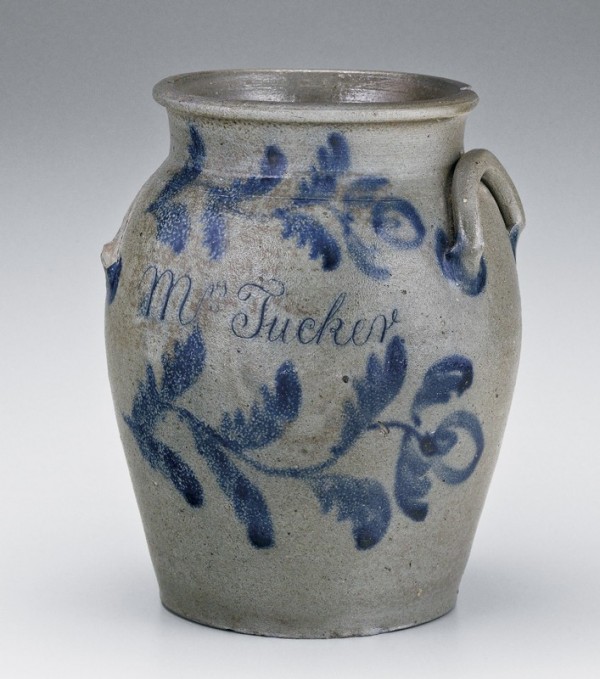

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849, Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 5/8". Incised, in script: “Mrs Tucker” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Incised, in script: “Margaret Cox”; “Quinces” (Courtesy, Virginia Historical Society; photo, Kurt Russ.) The cobalt floral decoration matches that on the jars illustrated in figs. 30 and 33.

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. not recorded. Capacity: 1 gallon. Incised, in script: “Ann R. Randolph / August 23, 1836” (Photo, courtesy MESDA Research Files.) Although the form of this jar matches those illustrated in figs. 31 and 33, including the sharp, slightly raised lip or ridge at the base of the neck, the decoration decidedly does not. The broadly amorphous brushed florals were executed by a different decorator.

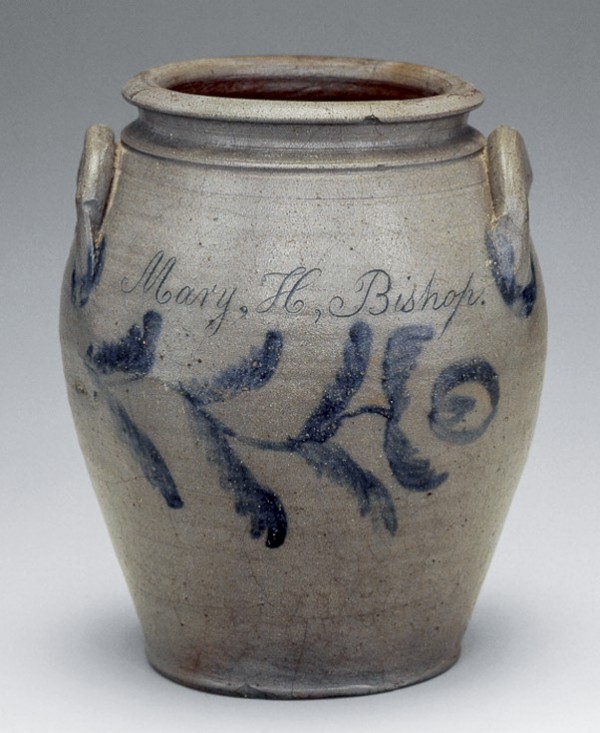

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/4". Incised and highlighted with cobalt: “Mary H. Bishop” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

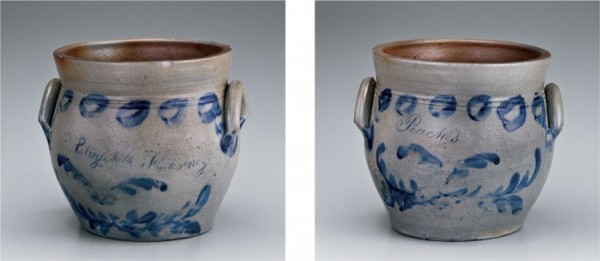

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8". Incised: (front) “Elizabeth Flournoy”; (reverse) “Peaches” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage-jar fragment, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. Partial inscription: “Fussell & Elyson” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jar fragment, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; Robert Hunter.) Note the horizontal undulating-vine decoration.

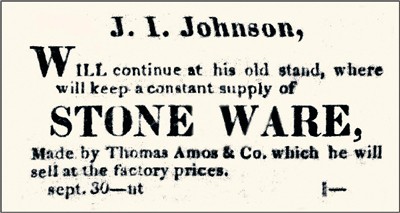

J. I. Johnson advertisement in the Richmond Commercial Compiler, September 30, 1819, p. 3-3.

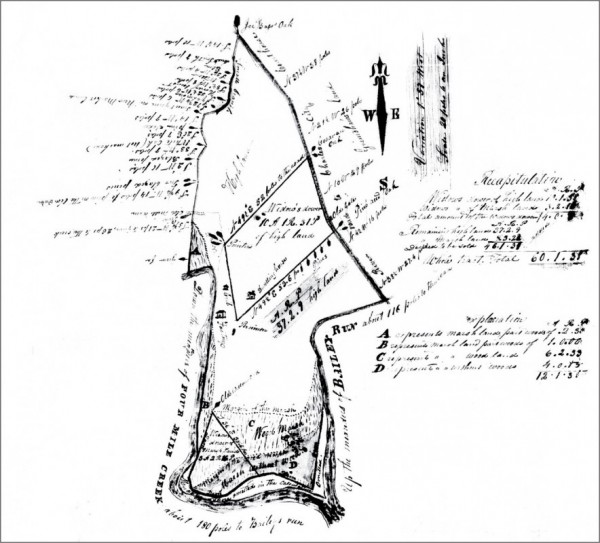

1841 survey of Factory Tract, land owned by Richard Ellyson. (Courtesy, Library of Virginia.)

Fragments, attributed to the Thomas Amoss pottery, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These archaeologically recovered sherds from the Henrico County site show rim, handle, and decoration matching those on locally discovered vessels.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Amoss, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1822. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg.)

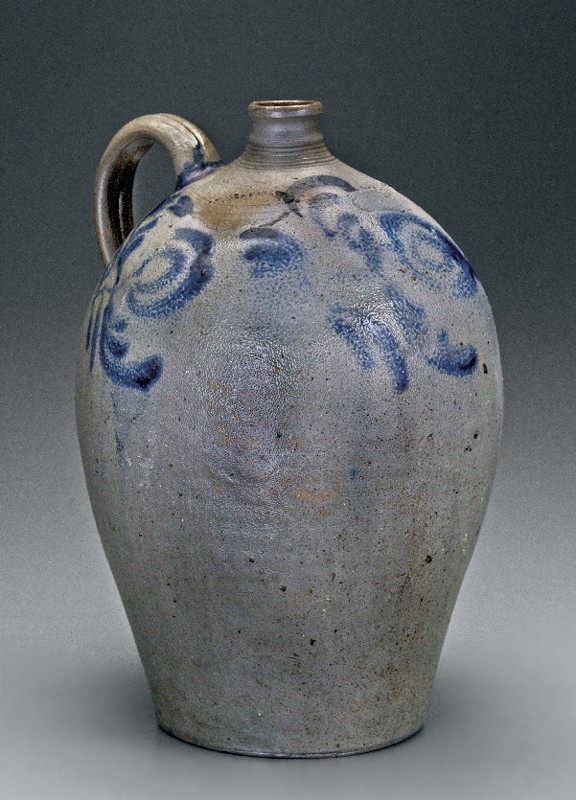

Jug, attributed to Thomas Amoss, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jug, attributed to Thomas Amoss, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1823. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Collection of salt-glazed stoneware wasters, Henrico County, Virginia, 1818–1849. (Photo, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The variety of forms and decorative treatments help differentiate the makers. Amoss, Frayser, and other potters are represented in these examples.

Detail, “Map of Southeast Virginia,” 1862, U.S. Department of the Army, showing the location of both Sweeney’s pottery of ca. 1844–1863, labeled “S. Sweeney’s Pottery,” between and just above the forks of Four Mile Creek and “Bailey’s Run,” and Sweeney’s “Pottery and Hotel,” shown just to the northeast of New Market Road. George B. Davis et al., The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War (1891–95; repr., New York: Gramercy Books, 1983).

Salt-glazed stoneware fragments at the Stephen B. Sweeney pottery site. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jug, attributed to Samuel Frayser, Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1849. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 3/8". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The concave neck with concentric reeding is common in the archaeological specimens from Four Mile Creek made by Frayser and Amoss, while the floral decoration is common to Frayser-attributed wares and likely precursors to later Sweeney motifs.

Churn, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 21 7/8". Capacity: 5 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pitcher, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Jar, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jar, Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jug, Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The blossom configuration of the brushed blue-cobalt floral motif on the front of this jug was undoubtedly influenced by Amoss. The blossoms of the lateral flanking motifs are more common in the Sweeney decorative repertoire.

Storage jar, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Capacity: 1 gallon. (Private collection; photo, Kurt Russ.) The decorative motif is a brushed-cobalt dancing man beneath one of the handles.

Storage jar, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Stamped capacity mark: “5” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This ovoid vessel displays a well-defined incised and cobalt-filled rooster, or game cock, standing on cobalt festoons similar to those seen on other Sweeney and Schermerhorn vessels, such as the jar illustrated in Russ and Schermerhorn, “Rocketts’ Red Glare,” p. 72, fig. 14.

Storage-jar fragment, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Pitcher, Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 3/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Butter-crock fragment, Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. Inscribed: “R. Cla . . .”; “Stephen B. Swe . . .” (Private collection; photo, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The decoration on this waster fragment is a fish or a bird between the incised inscription and Sweeney’s partial signature. Speculation on what the inscription refers to includes names of local families, such as Claiborne or Clay, or of a nearby landowner, Clarke.

Storage-jar fragment, Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Private collection; photo, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) Incised and cobalt-filled bird and floral decoration embellishes this shoulder remnant from a four-gallon jar.

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". Capacity: 3 gallons. Incised on base: “Richmond” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the capacity mark on the jar illustrated in fig. 58. The distinctive capacity mark distinguishes these Group I wares attributed to Samuel Wilson working with John Schermerhorn.

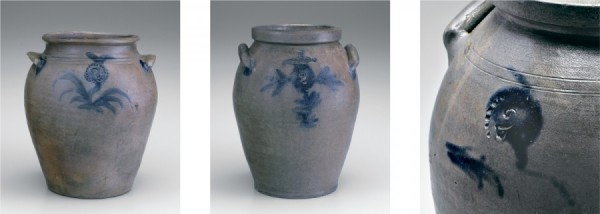

Storage jars, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left) 11 1/4"; (middle, right) 12 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pitcher, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/8". Capacity: 1 gallon. Impressed: “KELSO” (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The floral decoration is virtually identical to that on the jar illustrated in fig. 63 (right).

Storage jars, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. of jar on right 11 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Kurt Russ.)

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Storage jar, attributed to Samuel Wilson and/or associates, Richmond or Henrico County, Virginia, 1817–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

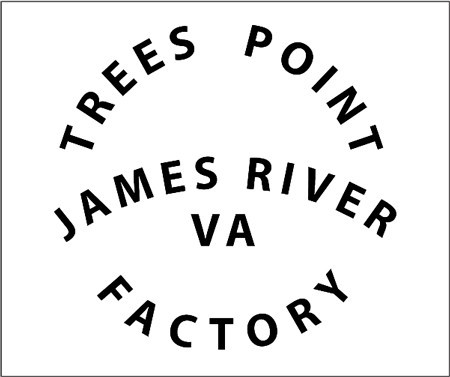

Map showing location of Trees Point Factory. (Courtesy, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) Wilson’s Landing is to the north in relation to the James River.

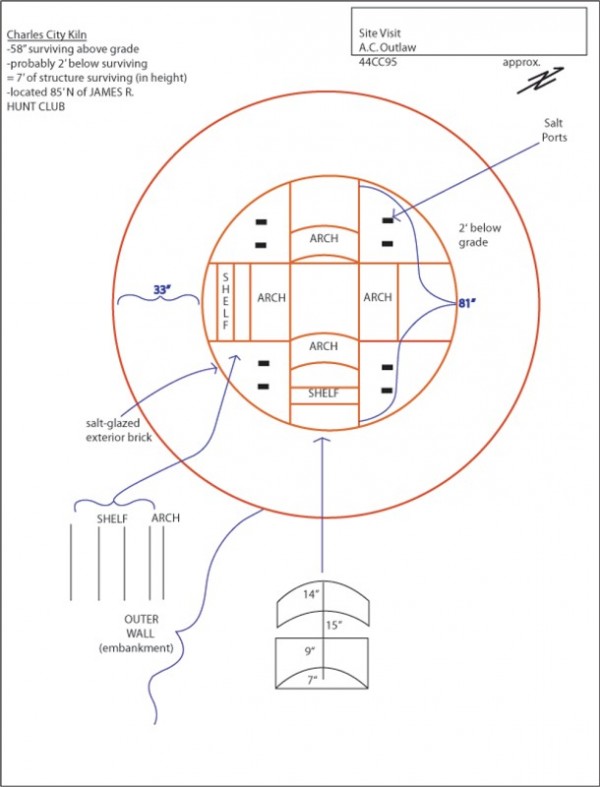

Field sketch or plan of Trees Point Factory kiln (1849–1853) by Alain Outlaw; traced by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.

J. P. Hudson examining the remains of an above-ground kiln, 1978. (Courtesy, Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary.)

Stoneware fragments, Trees Point Factory, Charles City County, Virginia, 1849–1853. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, William and Mary Archaeological Research Center.)

Rendering of maker’s stamp of Trees Point Factory. (Artwork by Oliver Mueller-Heubach.)

Storage jars, Trees Point Factory, Charles City County, Virginia, 1849–1853. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16" and 11 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Kurt Russ.)

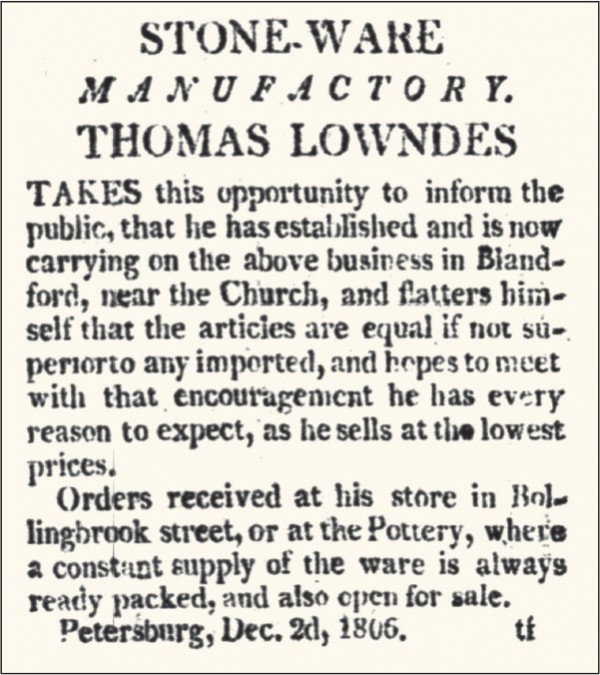

Advertisement, Thomas Lowndes Stone-Ware Manufactory, Petersburg Intelligencer, December 2, 1806, p. 3. This is an important early reference to a transplanted English stoneware concern about which little is known.

Pitcher, Henry Lowndes, Petersburg, Virginia, 1835–1840. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The classical shape of this elaborately decorated pitcher is typical of Staffordshire earthenware. The use of applied molding to the spout and the body is also influenced by British prototypes. The spread eagle, wreath, and stars all resemble decorative motifs incorporated in cast-iron decoration of the period. This pitcher is one of only two of this type known to exist.

Storage jar, Henry Lowndes, Petersburg, Virginia, 1841. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Capacity: 2 gallons. Slip-trailed inscription: “H. Lowndes / maker / Petersburg Va. / A.D. 1841” (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Churn, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Extant vessels have recently been identified that appear to have been produced by Sweeney but are decorated with a close variation on the Lowndes so-called Cotton Plant motif (see fig. 74). The branches are asymmetrical and the cotton blooms are less structured, more tightly defined, and sometimes executed with only two brushstrokes. These vessels may suggest an overlap between the two potteries either in the purposeful imitation of decoration or the exchange of workmen.

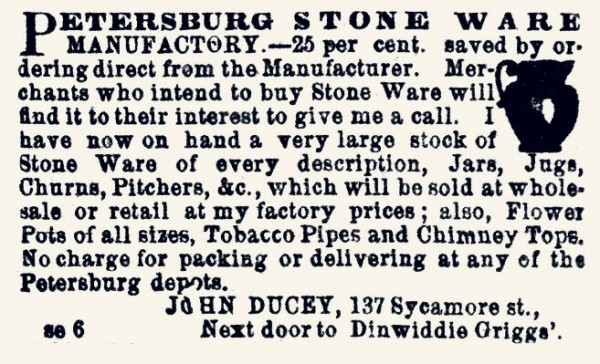

Advertisement for the Petersburg Stone Ware Manufactory, featuring the silhouette of a pitcher resembling earlier Lowndes Staffordshire-style ware. Petersburg Index, September 1872, p. 3, col. 3.

Storage jar, Thomas and John Ducey, Petersburg, Virginia, 1855–1872. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". Capacity: 3 gallons. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This well-made example of the Duceys’ work displays a deep-cobalt–brushed floral decoration, following the Lowndes style. Although scant research has been conducted on this pottery, a number of examples exist, both marked and unmarked. The mid-nineteenth-century forms tend to be straight-sided or slightly ovoid, typical of the period, although the decoration recalls earlier Lowndes pieces.

Nineteenth-century salt-glazed stoneware of the lower James River Valley has been actively collected for more than half a century, though little information about the potters and their wares has been documented in the literature. This article provides much-needed attributions, combining archaeological fragments from the production sites with surviving pieces in public and private collections. Most of the stoneware is embellished in blue cobalt, in styles from neoclassical to naturalistic. A surprisingly number of examples contains well-developed pictorial statements in themes from comic to political. Techniques include cobalt slip trailing, brushwork, and incising in the Germanic tradition with occasional nods to English brown stoneware and its forms. Many of the pieces are published for the first time. Viewed collectively, they reflect a bold decorative aesthetic rivaling long-recognized and celebrated schools of stoneware production seen elsewhere in eastern North America.

Although Yorktown, Virginia, was the home of America’s first successful stoneware pottery (1720–1745), it was not until the turn of the nineteenth century that expanding populations and recently discovered clay sources heralded widespread production of Virginia stoneware.[1] Potters hailing from England, Ireland, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania created a rich hybrid tradition with forms and decorations adapted from their regional styles. Their training of the native sons—white, enslaved, and free black—carried the industry through nine decades. Trade networks, such as roads, canals, and railroads, grew with the potteries, ensuring the spread of James River stoneware into southern, western, and coastal markets. The clay that brought these artisans to Virginia features proudly in geographic locales aptly named Kaolin and Claymount.

Whereas the stoneware industries of Alexandria and the Shenandoah Valley have been the subjects of extensive research and publication and have been nationally recognized for their contribution to American ceramic history, ceramics researchers have largely overlooked the stoneware pottery industry of eastern Virginia.[2] In the last decade, however, this began to change, and research on the stoneware potters of the Richmond and Petersburg areas has advanced rapidly. The topic was the focus of a 2004–2005 exhibit at the Virginia Historical Society and a related article in Antiques magazine in 2005 highlighting the diversity of stoneware produced in eastern Virginia from 1720 until 1890.[3] In 2012–2013 the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts hosted the symposium and exhibit “From Kaolin to Claymount: Demystifying James River Valley Stoneware.”[4] Most important, perhaps, is the research of Oliver Mueller-Heubach, contained in his 2013 dissertation “From Kaolin to Claymount: Landscapes of the 19th-Century James River Stoneware Industry.”[5]

The culmination of this research is a more complete picture of the historical depth and complexity of the stoneware manufactories once operating in Richmond, Petersburg, and the adjacent counties of Henrico and Charles City along the James River (fig. 1). As a result, a broader context can be established for understanding the significance of eastern Virginia stoneware, its potters, and production sites.

Earthenware manufactories centered in the Richmond area in the late eighteenth century probably involved only two operations and perhaps four potters. In contrast, stoneware manufacture in Richmond, southern Henrico County, Charles City County, and the Petersburg/Dinwiddie County areas involved as many as sixteen different operations and some forty identified potters. Those potters, who labored at various places at various times, alternating between cooperation and competition, were responsible for the production of a unique body of wares, tangible evidence of connections across space and time.

Richmond Pottery Production

Stoneware manufacture began in Richmond, Virginia, about 1807, having been preceded by a pair of little-understood earthenware endeavors (fig. 2). An intriguing early reference to Richmond white clay is found in a 1784 letter by James Brindley (1745–1820)—a canal builder who immigrated that year from England and settled in Wilmington, Delaware.[6] Brindley, who was involved in several canal projects, among them Virginia’s James River and Kanawha Canal, wrote to his uncle in England:

Wilmington, Aug.t 10th 1784

Dear Unkle—I rec’d your kind letter dated Aprill 5th 1784 with Cousin Taylors and 12 crates of Ware, come safe to hand. Cousen mentions sending a farther assortment which I hope will also arive safe. when request, You’l not send any more for the present, untill I can dispose of these and make good my remitance, when I will write you for the most saleable sorts and in the mean time make enquiring and try to fix you in connexion with some stanch able men. [Illegible] in this country which is probable will correspond with you to good advantage on all sides. Exclusive of what I can dispose of. As my time will be for the most part taken up in the canal business and presume you would wish to dispose of Large quantities of your manufacture of which I will inform you by first opportunity. You write me to send you some white clay that I mentioned in my last is at Richmond 300 miles from here nearly, but will endeavor to get some with some other that I have lately here of that’s any white.[7]

Just as English manufacturers were eager to market their wares to the region, so too were they seeking to extract raw materials with an eye to supplying new manufactories. These new works required advanced scouting for both “stanch able men” and identification of the “most saleable sorts” of wares. This late-eighteenth-century reference, though probably specific to kaolin clays for use in refined wares, is a prelude to later historical documentation of the significant clay resources for brick, coarse earthenware, and, especially, stoneware within the Richmond-Henrico County area.

Local production of wares, “equal or superior,” as they put it, to those previously imported from England, Germany, or the New York–New Jersey region, allowed Virginia potters to successfully expand their enterprises by offering competitive pricing. This enabled them to eventually dominate the market, with Richmond becoming a hotbed of stoneware production during the second and third decades of the nineteenth century. The influx of potters was no doubt influenced by a variety of factors—the restrictions of the Embargo Act of 1807 and the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, the War of 1812, and the potters’ desire to seek out new markets. Growing populations on navigable southern waterways would allow for market expansion and greater distribution of their wares.

Expanding Virginia businesses—pharmacies, distilleries, dairies, and mercantile operations—also created a demand that encouraged local pottery manufacture. The late-eighteenth-century advertisements placed by Richmond pharmacist Benjamin DuVal, for example, offered employment to potters able to supply wares for his business. Samuel Allinson was the first to answer this call, building and operating a kiln on a lot owned by Isaac Younghusband and managed by DuVal and partner Thomas Warren. William Harwood, the holder of a roof-tile patent, partnered with DuVal in 1809, furthering the enterprise begun by Allinson. Harwood may have been instrumental in expanding the operation into salt-glazed stoneware production two years later.[8]

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY RICHMOND POTTERES

Richmond was still a relatively young town in the late 1700s with imports largely satisfying local demand. As the city grew into its new role as the capital of Virginia after 1780, craftsmen arrived to feed the growing market. Earthenware potter Gresham (Gersham) Lord had arrived in Richmond about June 1781 in the company of John Robinson, another trained potter who resided with him.[9] The 1782 city census identifies one “Dresham Lord,” a twenty-nine-year-old potter, as having been “in residence for 9 months” in the area of Wardship No. 3 with John Robinson, potter, age twenty-eight.[10] Lord is not taxed for ownership of either real estate or other property.

By March 1782 Lord had partnered with a tanner’s son, Jonathan Park. Jonathan had continued the family tannery business, but after his father’s death offered it for lease in April 1783 and eventually dissolved it in October of the same year, perhaps in favor of devoting his full attention to the pottery.[11] It appears that Park used the proceeds (£20) from the sale of a thirty-acre lot “on the waters of Allen’s Branch, binding on Rocket’s line” in Henrico, to help finance his newly formed pottery partnership with Gersham.[12] Theirs was the first documented attempt to meet the growing local demand for utilitarian wares.

An advertisement in Richmond’s The Virginia Gazette, and the Weekly Advertiser, March 16, 1782, announces the establishment by Lord and Park of an “Earthen-ware Manufactory”:[13]

1782, March 16

Earthen-ware Manufactory.

The subscribers make and sell on the most reasonable terms, all kinds of course earthen ware, wholesale and retail. Orders will be carefully attended to, and furnish- on the shortest notice.

JOHNATHAN PARK.

GERSHAM LORD.

N. B. A likely boy or two will be taken as apprentices.[14]

Despite the fairly prominent location of their pottery on lot 85 at the corner of 18th and Grace streets, scant historical evidence of their operation is available today. Jonathan Park advertises as a tanner during this period and is likewise listed in the 1790 city census, suggesting his involvement with the pottery was primarily as a business partner.[15]

In February 1791 Benjamin DuVal and Thomas Warren placed the first advertisement for a potter “who understands working at the wheel,” setting the stage for an influx of northern potters to Richmond.[16] The next reference is from June 20, 1791:

“On the application of the proprietors of the pottery in this city, Resolved, that leave be granted them under the direction of the Committee of streets to make use of the dirt in the cross street between Scherer and Richardson’s houses.”

X Warren, Thomas[17]

The “pottery in this city” almost certainly is that of Benjamin DuVal and Thomas Warren (the latter undersigned the announcement). DuVal had advertised for potters only four months earlier, and this reference perhaps describes the first lot of clay procured for the pottery. Soon New Jersey Quaker potter Samuel Allinson and his journeymen John Carty and Richard Esdall of New York were producing ware, including earthenware cups, bowls, milk pans, and pitchers. Three years fraught with disputes between Allinson and DuVal may have left Allinson yearning for independence. In 1793 Allinson married Francis Johnson, and the next year he is noted “for building a potter’s kiln on a lot of Isaac Younghusband and burning earthen ware therein.”[18] A surviving 1784 deed to Isaac Younghusband shows his purchase of a 400-acre tract of land in the New Market vicinity, which could potentially have provided a clay source for his new tenant Allinson. As little as we know about these earthenware operations, less is known of their wares. No firmly attributed specimens of eighteenth-century Richmond-made earthenware have come to light.

BENJAMIN DUVAL & CO.

Benjamin DuVal produced clay roofing tile as early as 1808 on property north of Main between 23rd and 24th streets. By 1811 he expanded this operation to include the manufacture of salt-glazed stoneware. A number of newspaper advertisements detail a range and variety of products rivaling those of the best stoneware potteries in Manhattan and New Jersey. DuVal himself was not a potter, but hired potters from the north.

More is known about the DuVal pottery and its products than other Richmond-area stoneware manufactories. The site was first identified in 1978 through historical research conducted by Brad Rauschenberg, who initiated his research when the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), with which he was associated, acquired a large salt-glazed stoneware jar marked “B. DuVal & Co / Richmond.” Preliminary archaeological investigation directed by Norman Barka of the College of William and Mary subsequently confirmed the survival of this important historical site’s physical remains. In 2002 the site was destroyed by commercial development, but during the initial demolition of the property Robert Hunter and Marshall Goodman led an emergency archaeological salvage effort. An illustrated analysis of the vessel forms represented in the several thousand fragments they recovered is recorded in the 2005 volume of Ceramics in America.

The shapes of many of the DuVal pots are similar to those produced in the New York area. Based on the number listed in his advertisements and the quantity of recovered fragments, the most common vessel form produced at the DuVal pottery was the storage jar, in graduated capacities from one to five gallons. Jugs were also produced in graduated capacities. Pitchers of at least five sizes were recorded—a previously unrecorded one-gallon example is illustrated in figure 3. Other forms included bottles, flasks, chamber pots, and inkstands. As of this writing, however, fewer than ten marked examples of DuVal stoneware are known to survive.

JOHN POOLE SCHERMERHORN (1788–1850)

John Poole Schermerhorn’s association with DuVal was apparently short-lived. By 1817 he had left DuVal’s employ to pursue pottery manufacturing under his own name in Richmond (fig. 4). Schermerhorn’s well-situated manufactory at Rocketts, Richmond’s primary port, facilitated his production, marketing, and distribution, and he became the city’s most successful potter from 1817 until 1837 (fig. 5).[19] In addition to serving Richmond clients, Schermerhorn took advantage of water transport to sell up and down the James River and into the Carolinas.[20]

In the 2005 volume of Ceramics in America, Kurt C. Russ and W. Sterling Schermerhorn presented a well-illustrated summary of John P. Schermerhorn’s work in Richmond. Since that time, much new information has come to light about his endeavors and the attributions of some of his previously illustrated pots. Of particular note is the archaeological confirmation of a potting business at Schermerhorn’s home, Montezuma (fig. 6). Advertisements in the Richmond Enquirer between November 1828 and January 1829 first identify “Stone Ware on the Mechanicksville Turnpike, two miles from Richmond” (fig. 7). In them, Schermerhorn touts “a very large assortment of Stone Ware, much handsomer and of better quality” than offered previously. The wares were listed as available at both his factory and several retail outlets where orders were accepted from “Town and Country.”[21]

The discovery of the Schermerhorn pottery at Montezuma was reported as early as 2008. Oliver Mueller-Heubach conducted salvage archaeological work in 2010 after remains indicating the presence of a pottery kiln (heavily glazed bricks and kiln furniture) were found during development of the property (fig. 8). Although no maker’s marks were noted, the distinctive brushed-cobalt capacity designations known from extant Schermerhorn wares were well represented (fig. 9). Recovered fragments exhibit identical flaring rims, rather distinctive floral motifs, and brushed capacity numbers similar to those as found on a two-gallon tabletop churn attributed to Schermerhorn (fig. 10).

Previously unrecognized Schermerhorn vessels have come to light since the 2005 Ceramics in America articles. Of particular note is a group of three associated with Andrew Jackson (fig. 11). While already held as a military hero for his defeat of the British in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, Jackson’s perceived opposition to elitism led the yeomen, farmers, and laborers—potters among them—to think of him as the “greatest man of his age.” His wielding of the presidential veto, bordering on dictatorship in the eyes of opponents, further endeared him to loyal supporters. The Rev. John Freeman Schermerhorn (d. 1851), a close friend of President Jackson and one of two agents to sign the treaty of the Cherokee Removal, or “Trail of Tears,” was a distant cousin of J. P. Schermerhorn and is buried in the family cemetery at Montezuma.[22]

New research into Schermerhorn’s workforce has revealed the names of enslaved and free blacks who may have worked in the pottery. In 1828 he inherited Hall and Watt, two male slaves from the estate of Francis Wilson. At his death, Schermerhorn owned seventeen slaves, including six “adult” males—Archey, Ben, Charles, Henry, Ned, and William—as well as “one old man,” Davy.

Knowledge of which of Schermerhorn’s children were involved in this business is sketchy at best. One candidate is William Francis (“Frank”) Schermerhorn, born in 1817 to Schermerhorn’s first wife, Sarah Christian Wilson. Frank was in his teens when the pottery and house at Montezuma were built, and he would inherit the estate in 1850. John Poole Jr. was born to his father’s second wife, as was James Cornelius (b. 1832), who was eighteen at the time of his father’s death and the last of the sons conceivably trained in potting by John Poole Sr.

DAVID PARR POTTERY AND KEESEE & PARR POTTERY

A later Richmond operation was established circa 1850 by native Marylander David Parr Jr. (1819–1882). The Richmond City Directory first listed this “pottery at Rocketts” in 1852, then again in 1855 and 1860.

Parr had been associated with pottery manufacture in Baltimore from 1834 to perhaps as late as 1849. In 1860 he is recorded as living on Front Street (aka Rocketts/Lester/Main) with his sons John L. (1837–1895), David Preston (1838–1880), and James (b. 1843 or 1844), all of whom were listed as stoneware potters in Richmond’s Marshall Ward in 1860 and 1870; David appears as a stoneware potter in the 1860 Eastern Division Henrico census.

Potter George N. Fulton worked at Parr’s Virginia factory as early as 1855, and perhaps as late as 1862. He later went on to a long and well-documented career in the western part of the state, Alleghany County specifically. His brother Robert, also a potter, is listed as being in Richmond’s first ward and briefly worked with Parr. Another potter associated with Parr is Joseph B. Ramey (1830–1909).

In 1858 Parr entered into retail partnership with auctioneer Thomas W. Keesee (1819–1882), who provided an influx of capital into Parr’s operation. Keesee operated an auction house across from the Parr pottery as early as 1854, which he continued through the years of partnership.[23] Vessels marked Keesee & Parr (figs. 12, 13) were showcased at Keesee’s store at 12th and Cary streets, known as Carlton House, while business continued at the Parr factory at “Front Lower End Rocketts.” The Richmond City Business Directory of 1856–1857 does not mention either Parr or Rocketts; in the 1858–1859 directory, Keesee & Parr is the only pottery listed. The city business directory of 1860 describes the Keesee & Parr factory, located at “Front lower end Rocketts,” as an earthenware manufactory.[24] The 1860 industrial census describes it as a significant stoneware pottery, with $5,000 capital invested, sizable quantities of raw materials on hand (clay, sand, blue, and wood), and ten male workers, who were paid $200 in wages and produced stoneware worth $12,000.[25] David Parr Jr. was named as the manager of the business.

Like a number of their southern Henrico potter contemporaries, the Parrs were members of the Society of Friends. The Quaker Parrs had a profound impact on stoneware production and marketing in the Richmond area during the second half of the nineteenth century. Tilman [or Tilighman] Vestal, born to a Quaker potting family in North Carolina, was another craftsman who worked with Parr, in 1864.

Having kept his business going during the lean years of the Civil War, Parr was unable to protect his factory from the conflagration initiated during the evacuation of Richmond in April 1865. A large portion of the city, along with numerous other warehouses and businesses along Cary Street, suffered partial or wholesale destruction.[26] Not only was the pottery temporarily out of commission, but three months later the Carlton House store was consumed—and with it the Keesee & Parr partnership.

Evidence suggests that Parr’s operation was revived circa 1866 and continued until circa 1890. Parr newspaper advertisements grew sparse in the late 1860s, but in the 1870s they expanded their business with a flowerpot-molding machine, which they exhibited at state fairs and—as revealed by flowerpot wasters in a broad range of sizes—put to steady use. The Richmond City Directory of 1889–1890 lists John L. Parr as general manager of the Richmond Pottery Company at 3734 and 3736 Lester Street.

The business had wide-ranging and prolific production from which many examples survive, though relatively few are marked. They range from plain vessels to those bearing elaborate cobalt-brushed florals. Forms include straight-sided jars, jugs, pitchers, milk pans, cream and butter pots, fruit jars, bread risers, churns, bottles, water kegs and coolers, chamber pots, and spittoons, along with firebrick crucibles, furnaces, pipes, chimney sleeves, and so forth (fig. 14). Parr is also known to have produced special commission pieces.[27]

Parr may have taken over or occupied John P. Schermerhorn’s earlier Port Mayo, Rocketts, location.[28] The site of the Parr factory was investigated by archaeologists from the College of William and Mary’s Center for Archaeological Research in 2009. The extensive waster dump contained a wide range of vessel forms and decorative treatments as well as capacity and maker’s marks (fig. 15). An initial collection of this material was made and catalogued. No stoneware fragments were identified that suggested that the Parrs continued operations at Schermerhorn’s earlier Rocketts kiln. Nor were any in situ kiln remains identified, although a probable location across the road atop the bluff was suggested by the research.[29] The site continues to be threatened by urban development, and it is hoped that additional research can be undertaken before it is lost forever.

Henrico County Potteries

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF FOUR MILE CREEK/BAILEY’S CREEK AREA

Above a sharp bend in the James River ten miles southeast of Richmond, in southern Henrico County, Virginia, lies one of the unheralded heartlands of Tidewater history (fig. 16). Early on, John Rolfe’s plantation, Varina, arose nearby, becoming one of the eight original Virginia shires and serving as the Henrico County seat from 1634 to 1752.

As Richmond became the new seat of government, Varina’s fortunes waned, and much of the land became part of the Cox family plantation. In 1698 Curles, or Curles Neck, the next peninsula to the east, became a seat of Virginia’s Randolph family.

The area’s low-lying topography was improved with canals and levees, while natural elevations such as New Market Heights and Claymount became centers first of development and, later, of conflict. The area of Four Mile and Bailey’s creeks hosted movements of troops during the Revolution and particularly in the Civil War, when the battles of Deep Bottom, Malvern Hill, and New Market Heights encircled and scarred the landscape.

The establishment of numerous individual potteries drove the area’s growth and transformation. In the case of the Four Mile Creek/Bailey’s Creek area, a prominent and substantial mill seat was transformed with the creation of a pottery manufactory that could exploit nearby resources including fuel, water, rich clay, and mineral deposits. The channelization of streams and construction of canals facilitated the efficient transport of products via the James River. Soon, other potters were drawn to the area and what developed was one of the most significant nineteenth-century ceramic manufacturing complexes in the state, with four potteries and a half-dozen kilns in operation. Despite the absence of any signed wares from several of these potteries, comparisons of regionally collected extant wares with archaeological sherds from local sites provided tentative attributions for these identified operations.

RICHARD RANDOLPH’S POTTERY

Norwich Mills was an important eighteenth-century milling operation on Four Mile Creek. By the 1800s, however, it had fallen into disrepair. Speculator David Ross restored the mill and in 1809 sold the works, together with a potential contract for the miller, Samuel Ellyson, to Richard Randolph and his partner, Michael W. Hancock.

A 1781 map of the James compiled by Major Capitaine to aid American and French troops against Cornwallis includes the lands later owned by Ross (fig. 17). This map had been interpreted as showing the seat of Norwich Mills on Four Mile Creek just west of the split with Bailey’s Creek.[30]

At the time of Ross’s purchase, the tract was referred to as the “plantation called Norwich Mills” situated “between Bailey’s run on the east & fore mile creek south and the Lands of Thos. Matthews North in the county of Henrico.”[31] It contained eight buildings including a four-story merchant mill, a storehouse, a bake-house, a barn, a miller’s house, and three dwellings, one located “on the road” (figs. 18, 19). All of the buildings were of frame construction with the exception of the mill, which was brick and frame, and the bake-house and storehouse, which were of solid brick.[32]

By June 1809 Richard Randolph and partner Michael W. Hancock were the proprietors of Norwich Mills. In addition, and perhaps in an effort to ensure their continued successful operation, between the years of 1809 and 1815 Richard Randolph, in theory, oversaw the upkeep of some of the roads and bridges in the immediate vicinity of his land holdings. The upkeep of the local roads was essential to travel and the continuing economic success of the area.

After Randolph’s purchase the property was described as a full 500 acres, perhaps because of an updated survey, and located ten miles southeast of the courthouse and near New Market.[33] Randolph disposed of 136.5 acres in 1812, but held the remaining 363.5 acres (containing $500 worth of improvements) until 1820. The improvements included a pottery. On October 22, 1813, Randolph advertised as follows (fig. 20):

The Subscriber having established a manufactory of STONE WARE

On James River, twelve miles below Richmond, offers for sale at the manufactory (or delivered in Richmond,) a large and general assortment of stone ware, in quality equal to any ever imported. A constant supply of Soda, cyder and beer bottles, warranted to answer the purpose for which they are used. Orders left at the coumpting house of C. J. McMurdo

Will be attended to, and ware made agreeable to order.

October 23. Richard Randolph[34]

By 1816 the portion of the Norwich Mills tract insured by Richard Randolph consisted of a frame dwelling measuring 30 feet by 16 feet and a “two-storey potters shop” of brick, 40 feet by 30 feet. The improvements were described as lying some 100 yards apart and removed from other structures.[35] An earlier insurance policy for the property of David Ross at his plantation, Norwich Mills, identified a building C, described as a “Bake house of Brick covered with wood, 40 by 30 feet two stories high.”[36] On March 29, 1816, the building was reevaluated at $1,200 ($520 more than under Ross’s ownership) and plotted as building B.[37]

In an advertisement from July 4, 1817, entitled “KAOLIN,” Randolph offers for sale some 400 acres of his land and these pottery-related improvements (fig. 21). The Kaolin moniker promotes the property’s greatest resource—clays—suitable for both brick and stoneware production. The existence of a stoneware manufactory “distinguished for its excellent wares” suggests that finished products as well as the clays were being shipped via Four Mile and Bailey’s creeks. Randolph’s mention of recently adding “one artist” to an operation whose production was equivalent to $400–$500 per month hints at the economic potential of the area. In addition to the touted agricultural value of the land for producing grain and grass crops, the approximately 200 acres of wood and timber promised a standing fuel supply for the pottery.

The Census of Manufactures for 1820, however, does not list Randolph’s name (a mere four years after he insured his “potters shop” and associated residence), which suggests his pottery was operated by someone else.[38] It seems the property was not sold in its entirety, for in 1821 Richard Randolph transferred 335 acres (which included the portion containing $500 worth of improvements) of his then 363.5-acre Norwich Mills tract to Francis Lewis, who quickly enhanced the improvements to a value of $1,174. Lewis retained the land until 1828, when it passed into the hands of William Depriest, who, in turn, conveyed the property to Francis Frayser in 1835. Although Frayser died within a year, the tract remained part of his estate through 1850; the portions sold off were devoid of improvements.[39]

Personal property tax rolls from Randolph’s years as owner of the Norwich Mills tract indicate that he owned slaves.[40] Additionally, in June 1815 the overseers of the poor for Henrico County bound out to Randolph two orphaned brothers and free persons of color, Tom and Joe Givin (fourteen and twelve years old, respectively).[41] They are thought to have served as apprentices in his pottery business.[42] Coincident with this indenture, the overseers of the poor also bound out to Randolph’s New Market neighbor Samuel P. Parsons two brothers from the same family, Jack (age eighteen) and Frederick Givin (age fourteen).[43]

While it is unknown who was the first potter on Richard Randolph’s premises, it seems likely that Samuel Frayser leased from Randolph prior to establishing his own facilities (discussed below). Randolph may well have been an absentee landlord after 1817, particularly in light of the fact that just three days after Randolph advertised “Kaolin” for sale, Frayser was named overseer of the road from “four Mile Creek bridge to Little Cornelius’s.” This clearly indicates Frayser’s residence or employment in the immediate vicinity.[44] His appearance in the 1820 manufacturer’s census bears witness to his new, more significant role in the pottery business, while Randolph’s lack of inclusion suggests a diminished role, possibly exclusively that of landlord/lessor pending completion of the sale. Also of note is the fact that both Jackson and Caleb Frayser witnessed Randolph’s 1816 insurance policy for the pottery shop and house.[45] The presence of his family members living in the southern Henrico area, the fact that they were present as witnesses for the insuring of the pottery, and the subsequent purchase of the property by a relative, makes a strong case for Frayser being Randolph’s master potter.

In addition to Frayser and the Givins, it appears likely that Thomas Amoss was involved at Norwich Mills under Randolph. Randolph’s mention of “a recent addition of one artist” in his 1817 Kaolin property ad may refer to either Frayser’s or Amoss’s slightly later affiliation with his operation. Others who may have worked there during the Randolph years include Samuel Wilson, who worked for the DuVals and with John P. Schermerhorn. Isaac Denson had been apprenticed to James DuVal in 1818, but he may have left with Wilson when the DuVal Pottery closed the next year.

Surface finds from the property provide tantalizing clues as to the stoneware products of the Randolph-sponsored operation. Of particular interest are two fragments with a partial maker’s stamp (figs. 22, 23). The design is very similar to that used by Schermerhorn in Richmond.

Randolph’s initial 1813 advertisement announced the establishment of his “Stone Ware” factory and emphasized his “constant supply of Soda, cyder and beer bottles” (see fig. 20). Thomas Jefferson wrote to him in 1814 requesting stoneware jugs in two sizes—“quart jugs” and “pottles” (half gallons)—for his homemade beer at Monticello:

Dear Sir [Randolph] Monticello Jan. 25. 14

Will you be so good as to send me two gross of your beer jugs; the one gross to be quart jugs, and the other pottles do. they are to be delivered to a mr William Johnson a waterman of Milton, who will apply for them about a week hence. Mr Gibson will be so good as to pay for them on your presenting this letter. they should be packed in crates, or old hogsheads or such other cheap package as you use. Accept the assurance of my esteem & respect.

Th: Jefferson[46]

Although he also wrote to England for beer bottles, Jefferson heard of or saw the ad for the new Four Mile operation and may have wished to favor native industry and familial ties. In fact, a second request was made in late September that year for “four gross more” jugs to accommodate Jefferson’s new brew of “malt strong beer.”[47]

A recent comparison of bottle fragments recovered at Randolph’s pottery with those found at Monticello reveal matching forms with distinctive neck treatments and iron-oxide washed surfaces, confirming Randolph’s operation as their source. As this article was going to press, an intact example of a pottle was identified (fig. 24).

The most important information from the Jefferson letters is gleaned from Randolph’s response to the first request for beer jugs, in which he stated that “my best workman was in New York when I received your letter, he returned yesterday and will make your jugs next week, when they shall be forwarded agreeable to your directions.”[48] Viewed in the context of his 1817 addition of “one artist” to his Kaolin operation, it appears Randolph had respect for these craftsmen.

Randolph also provided kale pots for Monticello’s gardens. A sort of lidded bell jar, they were used to blanch or “bleach”— and sometimes force—young sea kale plants by sheltering them from cold and direct sun.[49] Packed around with heat-generating manure, the lidded pots allowed gardeners to inspect and tend the young plants inside (fig. 25). On February 21, 1821, seven years after his first request for bottles, Jefferson wrote to Edmund Peyton inquiring about “some earthen pots” for covering sea kale in his garden, which he had been told were made “at a pottery in or near Richmond.[50] Having requested at that time to be supplied with “1/2 hundred,” it was not until September 16, 1821, that he recorded “two pennies” being paid for bringing the pots to Monticello.[51] In his monograph Archaeology at Monticello, William M. Kelso notes a March 29, 1821, letter from Peyton to Jefferson referencing the original order “from Wickham from Richard Randolph’s pottery.”[52]

In May 1822 Jefferson again inquired of Randolph: “I do not know whether you continue your pottery. If you do, I will request 50. pots for the sea kale such as you saw here, which indeed are made on the exact model of mr Wickham’s. If delivered packed in hogsheads to the order of Colo. Peyton, he will, on sight of this letter, pay for them.”[53] Randolph did not elaborate on the status of his pottery—he was at this date no longer its owner—but responded to Jefferson as follows: “I have given directions for your bleaching pots to be made, and as soon as they are done, shall be delivered to Colo. Peyton.”[54]

Randolph forwarded Jefferson’s order to Thomas Amoss, who was then potting at the factory. Examination of fragments in archaeological collections at Monticello reveal both the plain Wickham examples and some that are attributable to Thomas Amoss’s production at Four Mile Creek (fig. 26). Decorated in Amoss’s characteristic slip-trailing, the pots were ringed in fine dots interspersed with what appear to be stylized kale-plant sprouts.

Randolph also had an association with the DuVal family. His daughter, Beverly, married druggist Philip DuVal (1789–1847), Benjamin DuVal’s son. Preliminary analysis of fragments found at Randolph’s pottery shows that many of the vessels share attributes with those produced at DuVal’s Richmond pottery, suggesting they may have made by the same potter, a past apprentice, or someone with similar training, perhaps in New York.

SAMUEL FRAYSER’S POTTERY

Samuel Frayser (ca. 1787–1849), identified in the 1820 census of manufacturers as the proprietor of a pottery factory, purchased 63.5 acres from William Hobson in 1818.[55] The acreage lay twelve miles southeast of the Henrico courthouse, probably on Four Mile Creek or Bailey’s Creek, near Newmarket. His appointment as overseer of the road from Four Mile Creek to Little Cornelius’s on July 7, 1817, suggests he was living in the vicinity prior to the establishment of his own operation.[56] On December 12, 1821, he married Elizabeth Francis Weymouth and they had two children, Samuel Jr. and Ann E.

Despite Samuel Frayser’s listing as the proprietor of a pottery factory in 1820, improvements on his own land were not erected until 1824, and his official residence in Henrico County was not established until 1826, suggesting his probable employment working with either Schermerhorn in Richmond and/or for Randolph in Henrico prior to this time. Like Schermerhorn, Frayser was a private in the Virginia Militia during the War of 1812; they both served for over a year in 1812–1813 in Captain Robert Gamble’s troop of Calvary, 19th regiment, Virginia Militia, commanded by Lt. Col. John Ambler.

One possible scenario is that when Schermerhorn first visited the region in 1810–1811, he encountered Randolph and perhaps Frayser and learned of Randolph’s plan to establish a pottery on his recently acquired Camp Holly acreage. Schermerhorn, or one or more potters traveling with him, might have agreed to stay and assist Randolph. Although Schermerhorn was soon employed by DuVal, a fellow northern potter might have remained to become Randolph’s first potter. On the other hand, it is equally plausible that one of the master potters involved in earthenware production in Richmond circa 1782–1794 made his way downriver to establish and run Randolph’s new pottery, perhaps instructing Frayser in the trade. A third, less likely possibility is that Frayser continued to work with Schermerhorn but, circa 1820, established his own operation on land purchased from Hobson in 1818, on his relation Francis Frayser’s land in the vicinity of Deep Bottom and Varina Road, or at some other location. He might also have run the Amoss operation after the Quaker’s death.

The Henrico County 1820 Census of Manufacturers recorded Samuel Frayser as using 50 tons of clay, 80 cords of wood, and 15 sacks of salt, and employing 3 men and no boys, with 1 kiln, 2 wheels, and an annual payroll of $200, to produce “Stone Ware of all Kinds.”[57] His wares were advertised in Richmond by an agent, E. Redford, in 1820 (fig. 27).[58] Between 1822 and 1829 Frayser leased two adjacent buildings (valued between $3,000 and $3,250) in Rocketts. The dwellings were located at the corner of Bloody Run and Elm Street and were owned by widow Mary Weymouth, who may have been Frayser’s mother-in-law. Whether these served as a residence for him and associated workers or as a warehouse, or both, has not been determined.[59]

At Norwich Mills, Frayser may have worked alongside Randolph’s New York–connected “best workman.” Did he then become proprietor of the pottery as a lessee in 1820? If so, then the question becomes whether he established a separate facility on his own land circa 1824 or remained at Norwich Mills through its transition to his relative’s ownership circa 1835, or even to potter Stephen Sweeney’s purchase three years later.

From 1824 through 1849 Samuel Frayser was taxed on buildings that ranged in value from $125 to $225.75, and he continued to acquire additional land until his death, in 1849. Frayser’s son Samuel Jr., who was seventeen when his father died, would have been entering apprentice age in the early 1840s and may have worked alongside his father during this period. Some of the land Frayser Sr. acquired was in the vicinity of Gravelly Hill, an area of rich clay and mineral resources exploited by several area potters.[60]

Two groups of extant vessels have been attributed to Samuel Frayser Sr. The first bears decorative elements strongly associated with Schermerhorn, in particular the festoons and wreaths (fig. 28). The second group exhibits incised names in combination with horizontal garlands and leafy flourishes.[61] Vessels associated with the first group include two pitchers with matching garlands, one bearing the date 1836 within a wreath (which appears on another three-gallon example), and a smaller example by the same hand. A three-gallon storage jar with the characteristic fan or headdress-like motif and a series of smaller jars from the same production have also been identified.[62] The storage jars have distinctive, well-defined rims and necks and are characterized by ovoid forms, applied U- or crescent-shaped handles, dark clay bodies (typically with rough, thinly salt-glazed exterior surfaces), and brushed-cobalt florals that sometimes are composed of elongated curvilinear leaves. It now appears that a cobalt-slip eagle jar previously attributed to Schermerhorn is attributable to Frayser’s operation (fig. 29).[63]

The second group of Frayser-attributed wares is made up of five similarly shaped stoneware jars with related decorations and incised names. Intended as presentation pieces, the incised names are clues to the area of their manufacture and the historical associations of potters with neighbors, adjacent landholders, and contemporary political and public figures. These wares have been attributed to Frayser’s production at Randolph’s Four Mile Creek pottery.

The most recently discovered vessel of this group is incised “Mrs. Tucker” (fig. 30). A “store of John Tucker” was located just to the northeast of Richmond, along Mechanicsville Turnpike. Although only a short distance to the southwest of the Schermerhorn estate and a residence associated with Schermerhorn’s wife, the location was at least ten miles north of the Newmarket area potteries, including Frayser’s operation. Tucker might have sold wares from local potteries, Frayser’s among them. Presumably this jar was made as a presentation piece for John’s wife, Mrs. L. H. Tucker, who according to the 1860 Federal Census was living in Richmond’s third ward with her husband, John R., and five children.

A second jar bears the inscription “Margaret Cox” and relates to the Cox farm just a couple of miles from the pottery (fig. 31). A Civil War–era map shows Henry Cox’s large tract of land at the southern end of Varina Road, west of a Mrs. Frazier’s land and to the south of the Highland Road. West of the Cox holdings was a large tract along Turnpike Road near its intersection with Kingsland Road, identified as belonging to “E[dward] Cox.” This substantial landholding included Cox’s Ferry, located at the terminus of Turnpike Road on the banks of the James River. Another neighbor was William B. Randolph, whose one hundred acres adjoined land belonging to a Richard Cox. Despite its different form and clay color, the Cox jar exhibits horizontal garlands virtually identical to those on the Tucker jar (see fig. 30).

Similar in form and clay color is the third example, which is incised “Ann R. Randolph/August 23, 1836” (fig. 32). Several Randolph families lived in the vicinity of the potteries, the most significant being Richard Randolph, who was responsible for the establishment of a pottery on his property by 1813. Mid-century maps identify William B. Randolph with disparate land holdings, including land recorded as southwest of Richmond along the James River, westward of Turnpike Road, as well as a tract to the southeast of the Sweeney pottery several miles distant. William B. Randolph’s wife was Anne R. (1783–1830). Although the form of this jar is comparable to the other examples, the clay is decidedly darker with a rougher surface, the glaze is thinner, and the distinct decoration suggests an associated group of wares that was thrown by a different potter and/or decorated by a different hand. The similarity of form and inscription, however, suggest manufacture at the same pottery.

The fourth in this group is a semi-ovoid jar bearing the name “Mary H. Bishop” (fig. 33), who is identified in the 1870 U.S. Census as having been born circa 1811 and as a resident of the Varina area. At the time, she was the head of household and shared her household with Virginia (55), Andrew (24), Sarah (20), Nathaniel (21), Truman (16), Mary (2), and Susan (1). In terms of form and garland, the jar most closely parallels the Cox jar (see fig. 31). In fact, the Tucker, Cox, and Bishop jars undoubtedly were decorated by the same hand and most likely thrown by the same potter.

A squat, semi-ovoid, open-mouthed jar with applied crescent-shaped handles and a slightly flaring collar is the fifth and final vessel associated with this grouping (fig. 34). The name “Elizabeth Flournoy” is incised in handwriting remarkably similar to the other examples and appears on the front together with a series of five open circles across the upper shoulder and garlands or flourishes beneath and on the lower half of the vessel.[64] On the reverse is incised “Peaches” (accompanying similar cobalt florals), indicating the vessel functioned as a preserve jar, just as the Cox jar was intended for quinces.

Fragments recovered from the Four Mile Creek pottery help confirm the Frayser attribution of these inscribed presentation jars, while they also associate a decorative motif with a group of previously unattributed extant jars from the region. A recently recorded jar fragment bear a partial inscription interpreted as “Fussell & Elyson” (fig. 35). The names refer to two families with ties to both the Quaker community and the milling operations of southeastern(?) Henrico County. According to David Ross’s advertisement for Norwich Mills, “Mr. Samuel Ellison [sic], who lives at the Mills . . . would undertake the management and engage a small interest in the business as a partner [to the new owner].” The “Fussell & Elyson” fragment may reference a trade partnership with Ben Fussell’s mill a few miles to the northwest. Another recently found jar fragment bears the distinctive, horizontal vine garland associated with this group of pots (fig. 36).

THOMAS AMOSS POTTERY

Thomas Amoss, a Quaker, worked as a potter between 1818 and 1822 approximately ten miles southeast of the Henrico County courthouse on Four Mile Creek.[65] Yet another portion of Richard Randolph’s tract of land—forty acres acquired by William Dandridge with no improvements—was by early 1820 sold to Amoss. This was probably another undeveloped portion of Randolph’s original 500-acre Norwich Mills tract. The property is defined in the deed and associated indenture as

all that Tract piece or parcel of land lying and being in the Said County of Henrico on four mile creek to the Junction With Baileys run thence up the run to the main road, thence up the road to Mrs. A. Kidds line thence down Kidds line to the creek.[66]

By 1821 Thomas Amoss had erected $550 worth of buildings on the property, although they were not insured. The buildings likely served as the pottery manufactory listed under his name in the 1820 census of manufacturers, given it was the only land that he owned in Henrico County.[67]

Personal property tax rolls for Henrico County in 1818 and 1819 confirm Amoss as a resident. Shortly thereafter others apparently joined him, for in 1820 the rolls record two free white males of tithable age (another man and Amoss), two slaves over the age of sixteen, and two horses or mules. This labor force built and operated the Amoss pottery, which consisted of one kiln and three wheels, and “used fifty tons of clay, eighty cords of wood, and fifteen sacks of salt.”[68] J. I. Johnson, a Richmond merchant, advertised “a constant supply of STONE WARE Made by Thomas Amos & Co.” available for sale at factory prices (fig. 37).[69]

Within a year, the Quaker Amoss was no longer incongruously credited with the two slaves. Perhaps these were workers from Norwich Mills who resided with Amoss during construction of his own establishment. In 1822, however, he paid taxes on himself and an adult white male, and, curiously, another slave over age sixteen, as well as the two equines. Although Amoss died in 1823 before the tax assessor’s visit, his forty-acre parcel and its $550 worth of buildings were credited to his estate through 1832; his Henrico “stoneware factory” was bequeathed to his wife, Caroline, until her death, at which time it would go to their son, Edward N. Amoss. Edward may have been trained in potting by his father. His birth year is unknown, but Thomas’s will indicates Edward was under the age of twenty-one in 1822. Amoss’s estate paid taxes on two slaves in 1824, and two free white adult males and two slaves in 1825.[70]

Meanwhile, the value of the buildings on the late Thomas Amoss’s forty acres declined in value from $550 in 1830 to $500 in 1831. His estate might have been encumbered by debt, for in 1833 his property was transferred to John Whitlock Jr. by a court-appointed commissioner. In 1834 Whitlock conveyed the forty acres and $500 worth of buildings to Richard Ellyson. Ten years later Ellyson’s executor transferred widow Sarah Ellyson’s interest in the property to potter Stephen B. Sweeney, who in 1845 acquired full ownership of Amoss’s forty acres plus an additional 20.5 acres of Ellyson land.

Known as the Factory Tract, this 60-acre parcel, located just north of the juncture of Four Mile and Bailey’s creeks, is identified on a recently discovered 1841 survey of Richard Ellyson’s land completed at his death to identify his widow’s dower (fig. 38). Illustrated on the survey are a dwelling house, a “Factory,” a crib, and an old mill dam to the north; the plat depicts what are likely the remaining buildings of Randolph’s former tract (a portion of which was subsequently owned by Amoss).[71] “Factory” relates to pottery production at Randolph’s operation rather than to the earlier Norwich Mills. The old mill dam just to the north indicates that the former grist mill stood in the immediate vicinity.

Amoss’s own pottery might be represented by the paired kiln remains and associated linear waster dumps some 450 feet to the east, near Bailey’s Run, that seem to have formed the basis of Stephen Sweeney’s later operations south of Route 5. These features were recorded by archaeologists from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1980. Still visible are the realigning of Bailey’s Creek and the shoring up of its banks into sizable levees to prevent flooding. Clay pits on the high ground are open to the west, toward the earlier Randolph operation.

Vessels by Thomas Amoss are distinguished by cobalt slip used in the style of the Morgan and Amoss potteries of Baltimore (figs. 39, 40). Indeed, historical evidence shows that several Baltimore potters influenced or were involved with the production of stoneware in Virginia from about 1818. In most cases, Henrico vessels exhibit darker clay and somewhat more robust, less elongated forms than their Baltimore counterparts. Amoss’s forms, some of the scarcest of the extant wares from the region, include semi-ovoid storage jars, pitchers, and jugs (figs. 41, 42).

The influence of the Morgan family of potters working in Baltimore on Thomas Amoss’s Virginia production was significant. The firm of Thomas Amoss and Co. owned by Thomas Morgan and Thomas Amoss operated in Baltimore from 1815 until 1819.[72] Amoss’s Henrico products are semi-ovoid vessels with well-defined collars and somewhat diminutive, slightly rolled rims and a defined edge above curved tab handles with blunt ends. They often are brushed with cobalt at their shoulder joint. A characteristic design consists of swags of paired, cobalt-dotted lines hanging from a central flower head and the narrow ends terminating at the handles. No signed Amoss Virginia wares are known. Recovered fragments from the bed and bank of Four Mile Creek near the Randolph kiln display a diversity of new motifs (fig. 43).

STEPHEN B. SWEENEY’S POTTERY

During 1838, one Stephen B. Sweeney purchased four contiguous tracts of land consisting of 92.5 acres, 51 acres, 39.5 acres, and 8.5 acres, located near “Baileys Old Field,” from Samuel Garthright Sr.’s executor. In 1839 the tax assessor indicated that $800 worth of buildings had been added to the 8.5-acre tract, which previously had only $150 worth of improvements. The following year, the assessor consolidated Sweeney’s land into a 186.5-acre tract and recorded that Sweeney had sold off 5 acres to Jane Pleasants. By 1844 Sweeney had disposed of 2 more acres, retaining the 184.5 acres and the parcel’s improvements, then worth $900.[73]

Working at or associated with the Sweeney pottery at midcentury were Stephen B. Sweeney Jr., and potters Edward J. Clark (b. ca. 1830 in Virginia) and Walt (Watt) Green (b. ca. 1829 in Virginia), a free black. Green might have worked for Sweeney for as long as sixteen years by that time, and there is a chance he was related to a slave named Watt inherited in 1828 by John Schermerhorn from Francis Wilson. Stephen Sweeney’s will included nineteen slaves. The men listed therein include Anderson, Bill, Billy, Peter, Walker, Washington, and William, all valued at $800 each except Peter, who was assessed at $1,000 (perhaps he had some specialized training). It is unknown who among them worked in the pottery as opposed to Sweeney’s contemporaneous agricultural pursuits, such as wheat, corn, and livestock.

By 1860 Stephen B. and Virginia Hughes Sweeney’s youngest son, Charles Henry Sweeney (b. 1841), was potting, as was one Patrick Murphy (b. ca. 1835 in Ireland), identified as a stoneware potter. Sweeney’s other sons could have worked in the shop as well. Martin (b. 1826) would have been entering his teens when his father established his first pottery. Stephen B. Jr. (b. 1839) and Charles might have begun work there in the late 1840s and 1850s, before they went on to their known careers.

Sweeney’s 1844 purchase of the 40.5 acres with $500 worth of improvements from Ellyson’s estate represents the addition of the former Randolph and Amoss pottery sites to his holdings. Sweeney held this acreage together with an additional 20.5 acres of Ellyson land well into the 1860s, by which time the tax assessor combined it with the large tract Sweeney had acquired in 1838.[74] In fact by 1854 the assessor had consolidated Sweeney’s parcels into a 237-acre tract that Sweeney christened “Claymount” for its abundance of potters’ clay. The property then had $2,000 worth of buildings and was described as situated thirteen miles southeast of the county courthouse. Among the buildings were “an excellent dwelling, kitchen, stables, barns, carriage house, sheds &c., all in good order.”[75] In 1860 Sweeney’s stoneware pottery was described as having $1,000 of capital invested with workers earning $150 per year resulting in stoneware production worth $3,000.[76] Period maps show the location of Sweeney’s “Pottery & Hotel” north of New Market Road and east of Bailey’s Run, as well as the later expansion of his holdings to the southwest to include the 1844 property just north of the fork of Four Mile Creek with Bailey’s Run, labeled “Sweeney’s Pottery” (fig. 44).

Sweeney remained in possession of Claymount and its improvements until his death in 1862. As he prospered he purchased some small parcels near Gravelly Hill, among them a 13-acre and a 15-acre tract.[77] These purchases, together with Samuel Frayser’s earlier purchase of land in the immediate vicinity of Gravelly Hill, suggest that there was a natural resource, presumably clay or temper, that was useful in manufacturing pottery.[78] By 1862 the Claymount lands included about 500 acres along the east side of Long Bridge Road and the north side of Route 5. In time, the northern branch of Bailey’s Creek, which cut through the property, became known as Sweeney Creek.

Southeast Henrico potters’ close ties to Richmond are evidenced by an 1860 listing showing that Sweeney was leasing a retail outlet on 14th between Cary and Dock streets. As early as November 1858, this building was insured under the title “Earthen and Stone Ware Store of Stephen B. Sweeney.”[79]

Sweeney’s will and the appraisal of his property provide some additional potting-related details. The administrator of his estate records several sales of stoneware: three separate lots sold in 1862 on October 3 (for $3.75), October 12 ($5.00), and November 12 ($2.50), with the largest lot going to David Parr on January 17, 1863, for $365.58. Among the other items listed were six “Turning Tables for Ware,” which presumably also sold to Parr, for $30.[80] Sweeney is also credited with owning four lots of land in Charles City County with an aggregate value of $738.75. The fact that another Four Mile Creek/Bailey’s Creek potter held land of significant value there supports the possibility of a pottery in that area, possibly involving Schermerhorn and/or Wilson and others.

Today, the area north of Route 5 (New Market Road) and east of Bailey’s Creek across from the site of the Norwich Mills/Factory Tract is heavily wooded, yet it is certain that this is where Stephen B. Sweeney potted for some twenty-four years, beginning in 1838. A plethora of maps and documents confirm this location, which is often referred to as “Sweeney’s Pottery and Hotel.” Massive waster deposits and kiln remains north and south of the road are the only vestiges of his once-thriving pottery enterprise (fig. 45). Although this site has been identified for decades, it has yet to benefit from any preservation protection or concerted archaeological research.

Sweeney stoneware vessels generally exhibit more variation in decorations than do Schermerhorn’s wares. In addition to semi-ovoid storage jars ranging in capacity from one to five gallons, pitchers from one pint to three gallons, and jugs with forms closely resembling those produced in Richmond, churns have also been identified, all sharing similar decoration (figs. 46-48).

The most common decorative treatment consists of a single floral stem, extending from two opposing outlined leaves, that terminates in a circular blossom. In many cases the blossom is rendered without stem and leaves, appearing cloudlike (fig. 49). Ongoing research is documenting the many decorative variations used during Sweeney’s tenure. A common decoration is a simple squiggle around the shoulders of storage jars that is brushed in blue cobalt and sometimes paired (fig. 50).

Sweeney’s vessels exhibit increased standardization in form as well as fine-grained, well-processed clay reflective of a later period. Similarities in decorative motifs help link them to vessels attributed to Schermerhorn, Frayser, and, in some cases, Amoss (fig. 51). Incised animal decoration with cobalt is extremely rare; brushed-cobalt depictions of both animals and human characters have been noted, but they too are scarce (fig. 52).