Interpreter at Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 2008. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Visible in this interior of a reproduction earthfast dwelling with a tamped earth floor are a shaved chair, a slab bench, baskets, turned bowls, and other wooden artifacts. All these artifacts must continually be repaired and renewed. This provides an opportunity to observe how the objects react to daily use. European paintings and prints help in the reconstruction of such assemblages, which represent interiors dating six years before the earliest extant Plymouth probate inventories.

Right panel from The Annunciation Triptych, attributed to Robert Campin (1375–1444), Brussels, 1425–1430. Oil on panel. 25 3/8" x 10 3/4". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, 1956 [56.70 a-c], Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art). Joseph’s settle encompasses various woodworking traditions in one object. The back has rectangular members united by draw-bored, rectangular mortise-and-tenon joints. The finials on the rear posts are sawn. The turned front posts, rails, arms, and side stretchers are shown assembled with cylindrical mortises and tenons. The interstices are filled with riven boards. Although it is not visible, the seat is probably constructed of multiple boards running front to rear and captured in grooves plowed in the front and rear seat rails. On Joseph’s workbench is one of the earliest depictions of a brace fitted with a spoon bit, the standard bit used to bore the joints of post-and-rung chairs. The workbench is of post-and-slab construction. The diagonal lattice in the upper panel of the settle’s back admits light to the work surface. It resembles similar lattice used in casement frames, sometimes to form ventilators, sometimes used to back oiled paper or thin cheesecloth.

Board backstool, or Brettstuhl, southeastern Pennsylvania, 1750–1775. Oak and pine. H. 32 1/8", W. 18 1/8", D. 14 5/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Henry Francis du Pont; photo, Laszlo Bodo). The Brettstuhl was a Germanic retooling of the Italian board sgabello, a mannerist scrolled and carved seat first used in grottoes and hallways. Eventually the Brettstuhl descended the social scale and became a type of Germanic folk seating, but even those chairs, like this Pennsylvania example, retain the elaborate construction techniques of the carved courtly versions.

Detail of the Brettsthul illustrated in fig. 3. This view shows the two external pins in the through-tenons of the back board and the dovetailed battens of the seat. The octagonal, tapered, shaved legs penetrate through both the dovetailed battens and the seat board and are back-wedged. Something like this construction is seen in prints and paintings of German or Dutch benches with slab or board seats, although their battens tend to be thicker and their stake feet often do not penetrate through the seat.

Slaughterer’s bench, probably New England, 1800–1875. Maple. H. 14 1/2", W. 55", D. 16". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Robert F. Trent in memory of Loren Jesse Pollock (1899-1973), 1983.302, photograph © 2008 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) This heavy workhorse is now almost colorless from being scrubbed with lye to neutralize blood. The rough top is made of approximately one-third of a maple trunk. The shaved feet are leveled in chopped and gouged housings and penetrate through the top, where they are back-wedged. Such benches were used principally for butchering swine and had to be heavy and level, for stability. Despite its superficial roughness, the bench is designed and assembled with precision.

Jan van der Straat, Preparing the Eggs of Silkworms, Florence, Italy, 1550–1575. Ink on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013). This drawing shows a set of at least three shaved chairs. They are the most elevated model found in Italian art. The chairs have rounded crests with molded edges and applied roundels, a row of spindles in the back, and conspicuous bridle joints at the tops of the posts. These chairs do not exhibit hewn layback or through-tapering of the sides of the posts. Despite the hobby with which the aristocratic women are occupied, the chairs are not low-seated and do not appear to be utilitarian in intent.

Hans Holbein the Elder (ca. 1465–1524), detail from The Martyrdom of Saint Paul, Augsburg, Bavaria, ca. 1504. Oil on panel. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Bayerischen Stadtsgemaldsammlungen, Munich.) This view shows a woman seated in a one-slat shaved chair with through-tenons and through-tapered posts. This painting was illustrated in Irving P. Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” Antiques 20, no. 4 (October 1931): 210–16, at p. 211, and was used in the formulation of the chairs shown in figs. 16–18.

Paul Velner, The Cobbler, in Das Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderstiftung zu Nürnberg, fol. 93 verso, Nuremberg, Bavaria, 1474. Watercolor on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Stadtbibliothek Nuernberg.) This cobbler is seated in a shaved armchair with stick arms and one slat. The posture of the cobbler suggests that the seat of this chair is normal in height. The posts appear to be slightly through-tapered on the sides. The artist incorrectly included a through-tenon on the side elevation of the top of the front post.

Hans von Kulmbach (ca. 1485–1522), detail from Birth of the Virgin Mary, Nuremberg, 1510–1520. Oil on panel. Dimensions and present location unknown. (Otto von Falke, Deutsche Möbel des Mittelalters und Renaissance [Stuttgart: Juluis Hoffman, 1924], p. 51.) The low-seated shaved chair in which the nurse swaddling the Virgin Mary is seated has one tier of rungs and two slats. The posts have long chamfers between the joints and what appear to be bent tops. Elsewhere in the room are a cradle with board sides tenoned into posts, a trestle table, a board bench with hinged back, and a stand with a spindle gallery to hold a bowl under a wall font.

Michael Sweerts, The Academy, Brussels, 1656–1658. Oil on canvas. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands.) This depiction of art students shows them seated on three-slat shaved chairs. The slats are roughly riven and have arc-shaped cuts on the ends on both top and bottom edges, save for the top slats, which have a straight bottom edge. The chairs are through-tenoned fore and aft but have blind tenons side to side. They appear to have seats about 14–15" high. Another important aspect of this view is that the chairs are part of a set of at least twelve chairs.

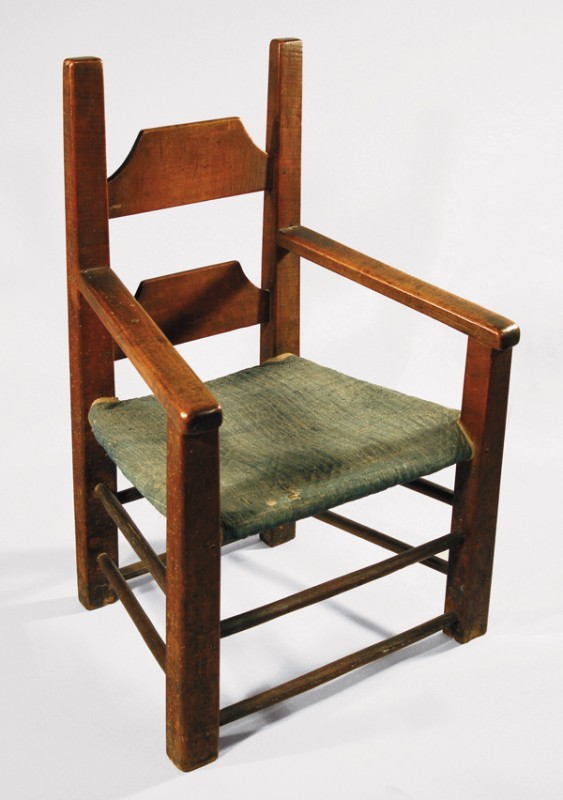

Armchair, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1650–1700. Maple and ash. H. 37 1/2", W. 25", D. 18". (Courtesy, Historic New England, gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann, 1942.3110.) Irving P. Lyon stated that this armchair was acquired by interior designer Henry Davis Sleeper (1878–1934) from the Choate House on Hog Island in Ipswich Harbor in 1919 (Irving P. Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” Antiques 20, no. 4 [October 1931]: 211–12.)

Armchair, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, 1650–1720. Maple, oak, and ash. H. 36 3/4", W. 20 3/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, H. E. Bolles Fund, 1971.190, photograph © 2008 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.) This chair displays the roughest workmanship of the surviving early New England shaved armchairs. Both arms and one side stretcher are either altered or replaced. Traces of red paint remain on the frame.

John D. Alexander Jr. and Robert F. Trent, armchair, Baltimore, Maryland, 1998. Oak. H. 38 1/8", W. 22", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

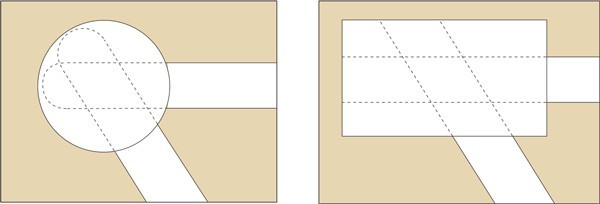

Layout diagrams of side stretchers entering posts. The left diagram shows stretcher tenons entering a turned post, where aiming the mortises for the center of mass is obligatory. The right diagram shows a similar approach in a chair with rectangular shaved posts, wherein the side joints are located at the center of mass, rather than the mathematical center of the rear face of the post. This practice ensures that the through-tenons on the front faces of the posts do not exit too near the front corners.

John D. Alexander Jr., armchair, Baltimore, Maryland, 1998. Oak. H. 38", W. 24 3/4", D. 18 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Many early European prints and paintings depict shaved slat-back chairs as slender as this example. Second or upper rear stretchers are rare in Anglo-American chairs but common in Continental examples.

John D. Alexander Jr., side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 2000. Red oak and white oak. H. 27 7/8", W. 18 1/2", D. 14 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Aspects of this chair’s design were derived from the Holbein painting illustrated in fig. 7.

John D. Alexander Jr., side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 2000. Red oak and white oak. H. 27 5/8", W. 18 3/8", D. 14!÷@". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) All of the study side chairs made by Alexander have through-tapered rear posts. The slats and tenons do not protrude as much as those on the chair illustrated in fig. 16, and the slats are parallel to the front faces of the rear posts. On many period chairs, the slats are centered on the inner faces of the rear posts.

John D. Alexander Jr., side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 2000. Red oak and white oak. H. 27", W. 19 1/4", D. 15". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The design of this example was influenced by chairs with shaved rear posts and turned front posts in Lyon’s article (Irving P. Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” Antiques 20, no. 4 [October 1931]: 213, fig. 8; 216, fig. 20).

John D. Alexander Jr. and Nathaniel Krause, side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 1998. Red oak; cotton canvas tape, and paint. H. 25 3/4", W. 15 1/2", D. 13". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, probably Braintree, Massachusetts, 1650–1700. Oak and ash. H. 34 3/8" (without rockers), W. 23 5/8", D. 18". (Courtesy, Concord Museum, Concord, Mass.) This chair displays severe tapering of the front and back faces of the rear posts above and below the seat but no taper on the sides. The slats are remarkably shallow in height and have discrete, arc-shaped cuts at the ends.

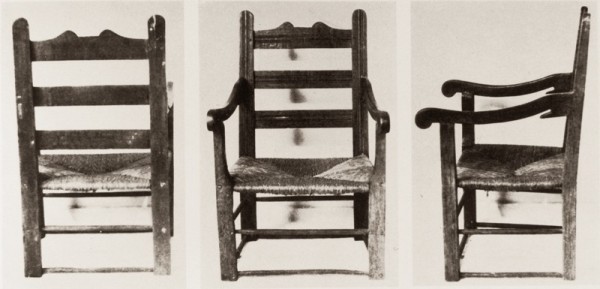

Armchair, eastern Massachusetts, 1675–1725, illustrated in Irving P. Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” Antiques 20, no. 4 (October 1931): 211, fig. 3. This chair has no provenance, but it seems early in date and is in the English tradition. Its posts are tapered in a manner similar to those of the Thompson chair (fig. 20). The three back rails are parallel to the front faces of the rear posts and are pinned, but they are not flush with the front faces of the posts. A central lobe may have broken off the center of the upper back rail.

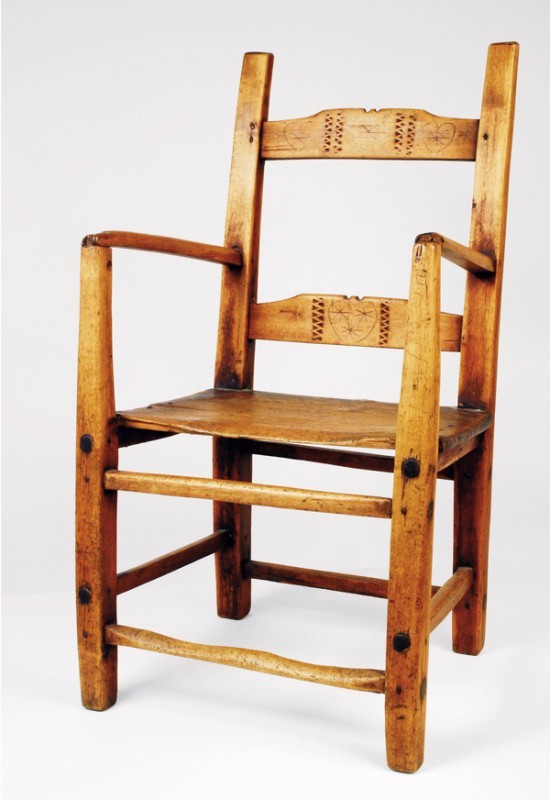

Armchair, probably Kingston, New York, 1650–1725. Oak. H. 37 3/8", W. 26", D. 18". (Courtesy, Senate House State Historic Site, Kingston, New York, New York State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although this chair has no history, it may have been collected in the Kingston area early in the twentieth century, when the Senate House functioned as a local historical society. The protruding tenons are the most pronounced seen in any early American shaved chair.

Detail of the right arm on the armchair illustrated in fig. 22. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker used a drawshave to shape the rounded ends. The arms are pinned to prevent the arms from rotating in their mortises.

Armchair, Sandwich, Massachusetts, 1719. Maple and ash. H. 36 3/4". (Brian Cullity, “A cubberd, four joyne stools & other smalle things”: The Material Culture of Plymouth Colony and Silversmiths of Plymouth, Cape Cod and Nantucket [Sandwich, Mass.: Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, 1994], p. 121.)

Armchair, Sandwich, Massachusetts, 1775–1800. Maple and oak. H. 39 7/8", W. 23", D. 23". (Benjamin Nye Homestead and Museum, Nye Family of America Association, East Sandwich, Massachusetts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The Nye armchair has lost about 6 inches at the bottom and probably has lost a tier of side stretchers and a rear stretcher. The arms are of a form associated with the third quarter of the eighteenth century, making this an extremely late shaved chair.

Armchair, Montague, New Jersey, 1740–1780. Maple and ash. H. 51 1/4", W. 23 1/2", D. 21 1/2". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) High-backed chairs of this size almost certainly date after 1725. The frame appears never to have had paint or a resin coating, and the inner bark seat may be the original one.

Photo showing the replacement of the broken front rung of a reproduction chair made by Robert Tarule for Plimoth Plantation. (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Peter Follansbee.) The broken front rung was removed by boring the tenons. The new rung is being driven through the front post toward the opposite mortise. The replacement rung must be pinned or back-wedged to remain in position.

Peter Follansbee, side chair, Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1998. Maple and oak. H. 32 1/4", W. 19", D. 15 1/2". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was charred while in use near a hearth. It has been cleaned but has not required any replacements. Undoubtedly many period chairs continued to be used after experiencing far more extensive damage than this.

Armchair, Keels, Newfoundland, 1800–1825. Birch and pine. H. 34", W. 26 1/2", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, The Rooms—Provincial Museum, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, Walter and Sally Peddle Outport Furniture Collection.) The joints are secured with small wooden pins, supplemented with nails in the seat rails. The rear posts taper above and below the seat in imitation of neoclassical joined seating. Chairs with board seats nailed or pegged to the seat rails commonly appear in vernacular seating from the British Isles, Ireland, and Canada.

Armchair, Topsfield, Massachusetts, 1725–1800. Maple and pine. H. 40", W. 26 1/4", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Parson Capen House, Topsfield Historical Society, Topsfield, Massachusetts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chair is stamped “D. LAKE.” Its frame combines joined, turned, and shaved work. The seat rails run side to side and the stretchers have rectangular mortise-and-tenon joints. All other joints have round mortises and tenons.

Side chair, probably Nova Scotia, Canada, 1820–1870. Birch and ash. H. 29 7/8", W. 14 3/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Plimoth Plantation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker used billets, or blanks, approximately 3 1/2 inch square for the posts. He probably began by striking lines first to establish the bottom part of the posts, then to establish the skews above the seat. The diameters of the stretchers are much greater than those of the tenons worked on their ends. The maker used a drawknife to shave the ends of the stretchers to conform to the diameter of the mortises. Because the posts were relatively wet at the time of assembly, they shrank around the irregular tenons, binding them securely.

Side chair, probably Wilmington, Delaware, 1730–1760. Sassafras. H. 40 1/4", W. 18 1/4", D. 17". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.) The posts have subtle tapers and scratch-stock moldings. Most of the joints have rectangular through-tenons, and all are back-wedged including the round seat rail tenons. Remarkably, many of the back-wedged joints are further secured by redundant pinning. The chair may have come from the Robinson House on Naaman’s Creek near the Delaware River in Wilmington. The core of the house probably dates ca. 1723, but the structure may incorporate portions of a seventeenth-century Swedish fort that stood on the site.

Side chair, Virgilina, Virginia, ca. 1903. Maple. H. 37", W. 17", D. 17 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, gift of Robert F. Trent.) The Moses Hall chairs were discovered by Halifax, Virginia, dealer Robert Pottage, who began acquiring them from local families in the 1960s. The chairs have flat riven slats and were never painted.

Settin’ chair illustrated in Henry Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), p. 230, fig. 66c. (Reprinted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press.) Glassie photographed this shaved chair while conducting field research in Gum Spring, Louisa County, Virginia, in 1966. Although he recalls seeing similar examples at that time, shaved settin’ chairs are rare.

Side chair, probably western North Carolina, 1860–1920. Oak and ash. H. 30 1/2", W. 18 3/4", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was found in an abandoned cabin in Burnsville, Yancey County, in western North Carolina.

John D. Alexander Jr., side chair, Baltimore, Maryland, 2005. White oak and red oak. H. 33 1/4", W. 17 1/2", D. 16 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interpreters at the re-created 1627 village at Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Masssachusetts, use reproduction furniture, woodenwares, and houses made with numerous woodworking techniques (fig. 1). Over the last fifty-five years, Plimoth Plantation has continually re-formed and replaced the buildings and furnishings, with the explicit goal of becoming more accurate. Some of the furnishings are based on surviving artifacts. However, Continental paintings, prints, and drawings have been an equally important source, not because of the Pilgrims’ experience in Leiden, but because seventeenth-century Continental graphics are particularly abundant and varied, whereas English pictorial sources are rare.[1]

The reproduction objects shown in figure 1 pose important interpretative quandaries. Numerous prejudices stand in the way of modern analysis of early New England woodworking, involving confusion about techniques versus historic trades versus modern classifications. The woodworker of the late medieval period inherited any number of furniture-making traditions. Objects produced by these artisans could include shaved and turned post-and-rung seating; chairs with slab or plank seats; trestles with stake or shaved feet; boarded and joined case furniture, tables, and seating; excavated or dug-out case pieces and seating; and structures made of staves or wood rods and vegetable fibers like straw, reeds, willow osiers, and inner bark. All these items were made of wood or other vegetable materials worked in a partially green state and required the use of tools with sharp steel cutting edges.[2]

In exploring early seating, too much has been made of the differences between shaved and turned post-and-rung chairs. The construction of both types of seating involved riving stock; rough shaping with hatchets, drawknives, and shaves; boring mortises with a spoon bit; assembly wherein moisture from wetter posts migrated to and swelled dry tenons; minimal pinning or back-wedging of joints; and no gluing. Some shaved or turned chairs were partially or entirely infilled with panels or with lattice held in grooves plowed in the inner edges of the frames. These chairs blur the distinction between turned and joined seating and, in the case of lattice, between furniture and architectural fixtures. For example, the settle depicted in Joseph’s workshop in the Merode Altarpiece combines latticework, joinery, turning, and shaving in one object (fig. 2).[3]

Equally confusing are chairs and benches made with shaved posts secured in slab or plank seats (post-and-slab or stake-and-slab, as opposed to post-and-rung). These range from the complex, Germanic Brettstuhl (figs. 3, 4) to utilitarian workhorses (fig. 5). The Brettstuhl, derived from the elevated Italian renaissance board sgabello, featured through-tenons with exposed, peglike wedges uniting the seat and back, as well as stake feet passing through dovetailed battens in the seat board, as well as the seat itself (fig. 4). It is impossible to force the Brettstuhl into any one technological category. It unites technologies from joinery, cabinetmaking, and post-and-slab chairmaking in one object.[4]

These assorted seating categories were not, therefore, mutually exclusive, even when guilds or other regulatory agencies sought to enforce the differences between them. Another important point is that rough surfaces or roughly worked components do not necessarily imply poor workmanship. The slickest veneered case piece can be shoddily constructed, and the roughest-looking post-and-slab bench can be a precision device with accurate, tight joints. The mentality that seeks to sort them into ideal types assumes that each technology belonged to a strict historical discipline. Period illustrations suggest that no such hierarchy existed, unless a guild system intervened. Even then, considerable litigation between London guilds suggests that the guilds themselves could not maintain strict separation between joinery and carpentry or between joinery and turning.[5]

Presumably distinctions between trades were greatest in urban settings. Even there, though, notable exceptions existed. Royal intervention and protection, which overruled guild regulations, were often extended to “strangers,” the term for skilled artisans from outside the municipality in question. This protection, often used to attract specialists from other nations, dispensed with protectionism and trade divisions, for the purposes of stylistic or technical innovation and fluid interchange between media.[6]

Also, urban centers were surrounded by rural enclaves, which supplied foodstuffs and fodder to the town or city. In such settings, other ambiguous forms of woodworking flourished, now generically referred to by the English as “field crafts.” Such diverse products included rail fencing and wattling; hurdles; rakes, scythes, and flails; basketry, winnowing fans, brooms, trays, bowls, buckets, shovels, and treenware; and yokes, carts, wagons, plows, tackling, and myriad other fixtures. One might extend this category to include larger features like houses, barns, mills, and outbuildings. Much the same could be said for commercial and military shipbuilding. Such things were and are not merely of regional, craft, agricultural, or military interest, and they often violated historical or modern trade boundaries, in terms of the technologies employed to fashion them. Furthermore, rural products were sold in urban enclaves, sometimes over the objections of guilds. Early-twentieth-century English studies of such products, based in an arts-and-crafts nostalgia for preindustrial country life, represented the first detailed recognition of green woodworking techniques and traditional woodworking.[7]

In essence, analysis of early woodworking cannot rely on artificial distinctions between technologies or on urban/rural contrasts or polarities. This is manifest in the case of simpler, turned or shaved, post-and-rung seating. In American decorative arts literature, such chairs are sometimes deemed to be evidence for isolated or deprived circumstances. The so-called “settin’ chair,” with two or more slats and either shaved or turned posts, was found in all regions of the Canadian Maritimes, Québec province, and the American South and survived into the modern era, when small factories produced such chairs for traditional households. Another incidental idea that accrues to shaved seating, in particular, is that it was so crude (in unspecified ways) that it must have been the work of amateurs, perhaps self-reliant pioneers who made such forms for temporary use until something better could be obtained. European paintings and prints suggest, rather, that shaved chairs coexisted with turned chairs and other seating in both elevated and humble interiors. Such depictions also show furniture forms made with various techniques coexisting in one room, in a manner that seems self-evident, but is not, even allowing all due compensation for artistic license.[8]

Another problem in interpreting shaved post-and-rung chairs is their poor survival rate, by comparison with the many early turned chairs that still exist. One cannot, therefore, assert that shaved chairs per se were common, although they were made throughout Europe and most European colonies. The eight known New England and New York shaved chairs that date from before 1800 are diverse in form, but some general observations about their design and workmanship illuminate the tradition as a whole and point to new directions for future study. Indefatigable furniture scholar Irving P. Lyon first published four of the early New England chairs illustrated here in a 1931 article entitled “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs.” Lyon noted that these chairs did not belong to any of the recognized seventeenth-century seating categories and refuted the idea that they were amateur productions by illustrating numerous European paintings and prints that included such chairs. The writers are indebted to Lyon, but we augment the discussion with discoveries made over the last seven decades. Another key contribution of this article is the explication of modern study chairs that explore the technology and design of shaved chair variants that do not survive. This is particularly true of side chairs, which are abundant in period illustrations but now are rare. A third contribution is the broadening of chronological, geographic, and ethnic representation of the tradition. Shaved post-and-rung chairs are not an obscure tradition from the distant past, but a widespread, continuous tradition that presents many opportunities for interpretation.[9]

Early European Shaved Chairs and New England Cognates

European paintings, prints, and drawings often depict shaved chairs (figs. 6-10) with posts that taper on the sides (fig. 7). Less commonly represented are chairs with posts tapered on three or four sides. When multiple tapers are shown, they usually occur on the rear posts above the seat. It is unclear if the long tapers of these representational chairs were hewn with a joiner’s hatchet or sawn lengthwise and then shaved and planed smooth, although hewing was a more common practice.

While some Italian renaissance shaved chairs are quite plain, others are embellished in the back with classicizing applied roundels or rows of turned spindles between the slats (fig. 6). A few have posts shaved into square balusters. The Italian interiors in which shaved chairs appear are, surprisingly, quite elevated. The scene is often the Birth of the Virgin. Concern for the status of Mary as spiritual royalty led to depicting the scene in a bedchamber of the Italian aristocracy. Women attending the birth use low-seated shaved chairs to tend fires, cook, wash linens, and swaddle the infant Mary (fig. 9). This suggests that low-seated shaved chairs were gender specific, at least in an Italian context. The Italian chairs usually have both through- tenons and blind tenons. That is, the posts tend to be somewhat broader than they are deep, and therefore the front-to-rear tenons are often through-bored, while the side-to-side tenons are blind.[10]

Many of the features seen in Italian and northern European art are found in early New England shaved chairs, as Lyon pointed out in “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs.” The armchair illustrated in figure 11 has a history of ownership in the Choate House on Hog Island in Ipswich Harbor. The chair has resided for the last eighty-five years or so in the Pembroke Room at Beauport, where it is drawn up to a table in a dark corner. Despite this obscure modern context, the Choate armchair represents the most compelling evidence that early American shaved chairs reflected the better European cognates and could be elevated in concept and execution. The chair exhibits extremely fine workmanship. The posts are exquisite, through-tapered forms, and they have deep, oblique chamfers on their outer corners to eliminate sharp edges. The rear posts are also relieved on their forward faces above the seat, to provide slight layback. The unusual slanted arms are also tapered and extend beyond the front posts. The rungs and seat rails are centered on the inner sides of the posts. Originally all the joints were blind, although some have broken through the outer surfaces of the posts later on. The original distribution of pinned joints is lost, because it appears that collector Henry Davis Sleeper (1878–1934), designer and owner of Beauport, instructed a cabinetmaker to glue and pin all the joints of the chair soon after he acquired it.[11]

By comparison, a Rochester, Massachusetts, armchair has much rougher components (fig. 12). The posts are square in section below the seat. Above that point, the sides of the posts taper slightly, and the rear posts are relieved on their front faces, as well. However, the layback of the rear posts is more complex than it seems. The rear posts above the seat taper on all four sides, a feature rarely seen. As in many of the shaved chairs, the slats are located on the exact centers of the inside faces of the rear posts. Curiously, this orientation of the slats slightly decreases the angle of their layback relative to the front faces of the relieved rear posts.

The Rochester chair has undergone some repairs that make it appear cruder than it was when first made. One or both of the arms may have been altered. The arm mortises are now exposed on the rear surfaces of the rear posts, although it is obvious that all the mortises were originally blind. It is possible that one or both arms were replaced or shortened in length, and one side stretcher may have been altered in length as well. One rear post has warped inward, probably soon after assembly. The overall result is that the chair is wrenched out of square, giving it an odd appearance.[12]

Armchairs Based on European Art and New England Armchairs

In the 1990s John D. Alexander Jr. and Robert Trent collaborated in making a shaved armchair based on the dimensions of the Rochester chair, as recorded by Peter Follansbee (fig. 13). We consciously altered the design to make the modern chair more like comparable examples depicted in European paintings: we reduced the cross-sectional dimensions of the posts and tapered them on the sides, relieved the front faces of the rear posts above the seat to provide layback, and introduced blade or riven arms. The latter detail occurs on some New England and New York turned chairs, but not on the Rochester shaved example. All of the mortises on the Choate and Rochester chairs were originally blind and those for the slats are centered on the back posts. To make our chair more like those represented in European art and to experiment with alternative construction techniques, we through-tenoned the rails and stretchers, set the slats 1/4 inch in from the front faces of the rear posts, and cut precise facets on the edges of the posts with a spoke shave. The Rochester example differs in having more deeply chamfered edges.

Because the front posts of our armchair taper to an extremely small rectangle at the top (1 3/4 inch deep by 1 1/2 inch wide) and the tenons of the seat rails and stretchers are a hefty 1 inch, we cut the mortises for the side seat rails and arms in locations different from those on the Rochester chair. In a post-and-rung chair, the frame is planned around a seat pattern established by the length of the rungs and the cross-sectional diameter of the posts (depending on whether the chair is turned or shaved). In this system, the front rungs are usually somewhat longer than the side and rear rungs, and the side and rear rungs are usually the same length. As the length of the front rungs increases relative to those of the side and rear rungs, the angle between the front and side rungs becomes more acute. Ordinarily chairmakers aim for the center of mass when locating the mortises for the side horizontal members (fig. 14). This is mandatory in turned chairs with round posts, but in shaved chairs with posts that are rectangular in cross section, several options for locating the mortises are available. To avoid having the through-tenoned arms and side seat rails and stretchers emerge too close to the outer corners of the front posts, one plots the mortises slightly inside of the absolute centerlines of the rear surfaces of the front posts. The result of these adjustments is relatively minor, but it seems that most period chairmakers avoided this problem by making their seat plans more squarish, by making the tops of their front posts wider, or by making their horizontal members smaller in diameter. In the case of the modern armchair (fig. 13), concern for where the arm mortises might emerge led us to reduce the diameter of the arm tenons from 1 inch to 3/4 inch.

Shortly after completing the armchair, Alexander began work on another example to explore other techniques that period makers may have used in the construction of shaved chairs (fig. 15). Many of the innovations on the second armchair derive from a classic post-and-rung chair Alexander has made for forty years (see fig. 36). The posts are narrower; the frame is 3 inches wider inside the posts; the frame has two rows of stretchers; the rear posts have severely tapering “heels” or relief cuts on the front faces below the seat; the slats have two pins in each joint; the seat height is 17 3/4 inches; and the rungs are %÷* inch in diameter.

This second armchair utilized the same placement of the side tenons as the first armchair. A refinement in the second armchair is tilting the blade arms slightly upward on their outer edges, so that they meet the sitter’s elbows exactly. An important aspect of this frame reflects the side elevation of the Thompson armchair illustrated in figure 20. The pronounced, tapering relief on the front faces of the rear posts below the seat automatically enhances the layback created by the relief on the front faces of the rear posts above the seat. That is, tapering the bottoms of the rear posts draws them farther in when the chair is assembled, and the back above the seat is thereby pitched back at a greater angle relative to the seat. One could not have anticipated many of these refinements if one had not made these two armchairs.

Study Side Chairs Based on European Precedents

After constructing the two study armchairs, Alexander made four side chairs that are variations on the small, one-slat shaved chair seen in late medieval and renaissance European art. The one-slat design, most familiar to Americans from Shaker turned sewing and dining chairs, is cheaper than a two- or three-slat format and makes for a more portable chair. While the seat was not exclusive to women, it certainly seems to have been associated with women’s work. The one-slat design also has strong ergonomic advantages. Unlike two- or three-slat designs that require hewn layback for comfort, one-slat chairs support the lumbar region but leave the thoracic and cervical regions free to relax slightly back. They seem to have been ubiquitous in early modern Europe, but the authors have not located an extant early example in any European museum. The four study chairs presented here are an important means to assess how such chairs were made and how they functioned.

The first study chair (fig. 16) has through-tenons both fore and aft and side to side. The front and rear posts have through-tapered sides. The posts had a high moisture content at the time of assembly. All the tenons now protrude far beyond the outsides of the posts. Some observers of European prints and paintings have assumed that chairs with protruding tenons are purely the result of joint failure and wracking. However, if chairs with through-tenons are assembled with wet posts, the posts will shrink far down the tenons. If the posts are oriented with the growth rings running from side to side, the shrinkage down the side-to-side tenons will be more extreme. However, wracking, or gradual loosening of the joints with use, can aggravate tenon protrusion. It seems that attempts to tighten the joints of some period chairs later on by driving the posts down the rungs were also common. The tenons of this first study chair are still secured in their mortises, save for the slat, which is somewhat loose but cannot escape. By contrast, the second study side chair (fig. 17) was made with through-tenons fore and aft but blind tenons side to side. The front posts are straight-sided, but the rear posts are through-tapered on the sides. The chair was assembled with posts that were drier at the time of assembly than those of the first chair. Almost all the through-tenons now protrude only slightly beyond the outsides of the posts. The tenons of this second chair are secure in their mortises. The third study side chair (fig. 18) combines a shaved back with turned front posts. This combination appears in some period sources and is challenging to understand. However, given the subtle levels of prestige attributed to different kinds of workmanship, it is probable that turned front posts slightly elevated the market value of such chairs. Another possibility is that round front posts were thought to be less likely to snag clothing.

Alexander and woodworking student Nathaniel Krause constructed a fourth chair to explore yet another detail seen in European art, a top slat set in open bridle joints (fig. 19). This construction seems counterintuitive, in that one would expect the slat to wrench out of the open joints during use. The open mortises obviously require that the slat be pinned. This chair has a slat secured with two pins in each joint. The locations of the pins were staggered to avoid splitting the posts, and the pins were driven at an angle, to force the slat down into the joints. This chair has not been subjected to use, and the joint has not been “tested,” but the many period depictions of such slats suggest that it was not regarded as precarious.

These four study chairs provide some important provisional ideas about the one-slat side chair. First, if the horizontal components are dry or below ambient moisture content at the time of assembly, such chairs could be made with posts that had relatively high moisture content. Second, projection of through-tenons caused by wet posts receding down the horizontal members as they dry is greater when the tenons are driven through the growth ring plane of the posts. Third, the low seat height of 14 1/2 inches is advantageous for using the chair for multiple types of work. A modern seat height of 16 1/2 or 17 1/2 inches is too high. The pre-1700 average seat height of about 21 inches would have made the contrast between work-height seats and regular seats all the more apparent. Fourth, the distance between the rear seat rung and the slat seems less critical to the ergonomic success of the design than seat height. Most one-slat side chairs in period illustrations seem to have slats about 8 inches above the rear seat rung. Narrower or broader slats may have helped in adjusting where the slat hit the lumbar region of shorter or taller people. Fifth, the heavier weight of chairs with posts that tapered from broad bases to narrow tops is offset by the greater stability of such frames. The heavier bottoms do not seem to have reflected a belief that they would wear longer or would be less susceptible to rot or insect infestation.

Shaved Chairs with Parts and Construction Evoking Joined Chairs

A chair with a history of ownership by Rev. William Thompson of Braintree, Massachusetts, is one of two New England examples reminiscent of joined or wainscot chairs (fig. 20). The Thompson chair displays an extraordinary side elevation on the rear posts, which are hewn away above and below the level of the seat; the hewing below the seat constitutes the “heels” alluded to above in connection with the second study armchair (fig. 15). The back posts taper from 2 1/4 inches deep at the seat to 1 1/8 inch deep at the top. Some loss at the bottom of the rear posts, associated with a later conversion of the chair to a rocker, makes it difficult to determine if the same amount of taper once existed below the seat. Currently the bottoms of the posts are 1 3/8 inch deep. If the bottoms extended two more inches, the posts would have achieved the same 1 1/8 inch depth seen at the tops of the posts. This dramatic tapering on the side elevations of the posts resembles that on the posts of some joined chairs. The flat scroll arms of the Thompson chair certainly have a distant relationship to those of French caqueteuse joined armchairs, which were influential in England. The arms of the Thompson chair are through-tenoned at the rear, and vertical tenons worked on the front posts emerge through the tops of the arms. These arm tenons are all pinned, as are the top and bottom slats.[13]

The so-called Wayland armchair, whose present location is unknown, is unquestionably the most joiner-like of the early New England shaved chairs (fig. 21). Remarkably, the Wayland chair has a back frame with three cross rails with rectangular mortise-and-tenon joints, combined with a shaved seat rail and two lower stretchers. The three back rails and the upper portions of the back posts are run with scratch-stock moldings of the sort associated with joined furniture. The arms have a vertical scroll profile with a rear scallop underneath, like those of joined chairs. As in many joined armchairs, the front posts are dramatically shaved away on the insides above the seat so that they are as narrow as the vertical scroll arms at the tops.

The rest of the Wayland chair’s frame conforms to the practices associated with shaved chairs. The rear posts were hewn to profile. All the fore-and-aft round seat rails and stretchers have through-tenoned joints, while all the side-to-side seat rails and stretchers have blind mortises. Ultimately one has to wonder why the maker of this chair did not simply make a full-blown joined armchair. Nothing more about this chair is found in Lyon’s papers, and the three photographs published in 1931 are the only record of it.[14]

Lyon published four of the New England armchairs illustrated here in 1931, but four additional examples have emerged in the last two decades. The shaved armchair illustrated in figure 22 is the only example that might have been made by an artisan working in the Dutch tradition. It is made entirely of oak, whereas most other shaved chairs have posts made of diffuse porous hardwoods and horizontal members made of ring porous hardwoods. The rear posts are relieved on their front faces above the seat, but the front posts are not tapered. All the joints are through-tenoned, and the protrusion of the tenons is extreme. This feature, which appears on chairs depicted in many northern European prints and paintings, suggests that the posts of the armchair had high moisture content at the time of assembly. The blade arms with rounded ends are another detail associated with northern European seating. Several New York turned slat-back armchairs in the Dutch tradition also share that detail (fig. 23). The usual blade arm seen in New England slat-backs has arc-shaped or concave cuts on the ends executed with the drawknife, like those on the study armchairs (figs. 13, 15); however, some of the Dutch-looking New York slat-back armchairs have arms with concave end cuts as well.[15]

Two shaved armchairs first published by decorative arts scholar Brian Cullity have histories of ownership in Sandwich, Massachusetts (figs. 24, 25). Both are probably late eighteenth century in date, if the slats and the finials are any indication. The chairs feature curved arms and bent and hewn front posts with cutbacks on the inner faces above the seat to more easily accommodate the sitter. The chair illustrated in figure 24 is virtually complete and has two rows of stretchers. To judge by the present seat height, it may have lost three inches at the bottom. The other chair (fig. 25) has probably lost a tier of stretchers at the bottom. This example, although modeled with shaving, is strikingly reminiscent of simple, rush-seated joined chairs made in many New England regions during the late eighteenth century. It is unclear if both these chairs were made in the same shop tradition.[16]

A more recent discovery is a large armchair that belonged to Jacobus Nearpass (1715–1805), a Prussian immigrant who settled in Montague, New Jersey, in the mountainous Delaware Water Gap, in the 1740s (fig. 26). While later generations of the family thought that Nearpass made the chair himself, nothing about the object suggests Germanic workmanship. The chair is extremely large and displays early baroque proportions. The arms are flat scrolls, much like those of the Thompson chair (fig. 20). All the joints are through-tenoned, and the rear posts are accentuated by slight hewing of the front faces above the seat, and the chair never had a coat of paint or finish. A noteworthy aspect of the frame is the extraordinary 14-inch distance between the seat and the arms. This suggests that such chairs were used with cushions; otherwise the sitter’s arms would have been forced up into an uncomfortable position.[17]

Plimoth Plantation Replica Chairs

Unlike the study chairs made by Alexander, shaved chairs made by Robert Tarule, Ted Curtin, Peter Follansbee, and others for use in the re-created 1627 village at Plimoth Plantation have received rigorous use and abuse by interpreters, both inside and outside the houses. The floors of the houses are tamped earth, and rot or insect infestation at the bottoms of the posts have required that some chairs be cut down in height. It seems that chair posts made of ring porous hardwoods (other than white oak) rot more quickly than those with posts made of diffuse porous hardwoods like maple. This may account for the preference for posts made of woods like maple or birch, rather than red oak, ash, or hickory.

Another problem is that the chairs rest on uneven floors. When chairs are sat on under those circumstances, the frames experience uneven stress on the joints because one or two posts are not in contact with the ground. Joints that are stressed in this manner often fail in specific ways, notably shearing of rungs, seat rails, or slats immediately adjacent to the posts. This kind of breakage requires replacement of broken parts. Through-tenoned rungs or seat rails are easily replaced. The broken rung is driven out, and a new one is inserted from the outside (fig. 27). Something like this procedure may have been followed in the old repairs to the Rochester chair arms and side stretcher (fig. 12).

Other damage involves scorching or charring (fig. 28). Period artworks reveal that low-seated chairs were used during cooking, as might be expected when women were moving and lifting heavy kettles off cranes, pushing skillets across the floor of the hearth, frying on griddles, or stirring pots. One chair at Plimoth Plantation was left too close to the fire and experienced severe burns. The burns were not enough to retire the object, but in the past, extreme charring might have led to replacement of parts or to discarding chairs altogether. Certainly this kind of damage helps to explain why low side chairs have not survived in great numbers.

The swiftness with which damage accrues on such chairs is remarkable. Most of these chairs have been in use only five to ten years, during the eight months a year that Plimoth Plantation is open to the public. They have almost all sustained damage, especially to the woven seats. At the same time, it is important to remember that even a damaged chair, or one whose joints have failed and begun to wrack, can be held together for an extraordinarily long time by the vegetable fiber seat alone. Whether these seats were made of twisted rush (usually called “flags” in New England) or of strips of flat or twisted inner bark (possibly called “bast” or “bass” in the seventeenth century), they were incredibly strong and could withstand considerable torsion as a failed chair swiveled around in its joints.

The Broader Tradition of Shaved Chairs in North America

Shaved chairs from other regions of colonial North America display structural variations comparable in variety to those seen in New England and New York examples. Many shaved post-and-rung chairs with round through-tenons from French-settled areas of Canada survive. Also relatively common are Spanish colonial shaved chairs with rectangular through-tenons and to a lesser degree round through-tenons. Four chairs from the Canadian Maritimes, Delaware, and Virginia give some indication of the range of technical and stylistic diversity seen in these later traditions and suggest the potential for future research.[18]

In 1986 furniture scholar Walter Peddle found the shaved armchair illustrated in figure 29 in the small fishing village of Keels, in the Bonavista Bay area of Newfoundland, about one hundred miles northwest of St. John’s. At first glance the Keels chair appears remarkably similar to the Rochester armchair (fig. 12) in having two slats and shaved arms. The Keels chair has a number of features not widely seen in earlier New England examples, however, and it probably dates 1800 to 1825. The slats have scalloped upper edges with a pronounced center cusp. This contour seems to reflect the scalloped crests of early baroque banister backs or the slats of earlier turned slat-backs. The scribed hearts and incised rickrack carving on the slats, while attributed by Peddle to Irish influence, also convey something of the complexity of fancy painting or carving seen on contemporaneous urban seating. The stretchers, seat rails, and arms oversailing the front posts are square in cross section, even though the through-tenons on their ends are round. They may have been intended to evoke early neoclassical joined seating, an impression that would have been stronger when the original reddish wash and brown varnish were new. The maker probably used birch as the primary wood because it resembles mahogany when stained.[19]

An armchair that descended in the Lake family of Topsfield, Massachusetts, is coeval with the Keels example and displays many similar traits (fig. 30). Like most close stools, the Lake chair probably had a stopper in the seat and an accompanying cushion. The seat board and the shelf for a chamber pot rest on the rails, requiring the maker to shave the top surfaces of the round side stretchers to accommodate the boards. Perhaps the most archaic aspect of the frame is the tapering on three sides of the rear posts above the seat. Undoubtedly this was what made Lyon think that the chair was seventeenth century in date. The turned arms may have been inspired by those on early-nineteenth-century Windsors.[20]

The Canadian chair illustrated in figure 31 has severely hewn rear posts and displays very rough workmanship. The rear posts taper on all four sides above the seat and splay to the side and to the rear. French-Canadian shaved chairs appear to survive in greater numbers than those attributed to other ethnic groups in Canada; however, some scholars believe that some traits of Canadian seating formerly regarded as French may reflect Irish influence.[21]

A chair that may be Swedish in derivation descended in the Robinson family of Wilmington, Delaware (fig. 32). Its design combines early baroque, high-backed proportions with late baroque Germanic detailing, including a scalloped crest, two vasiform banisters, and rectangular stretchers. The stretchers resemble the sawn balusters found on staircases and closet ventilators in the Delaware Valley.

The Robinson chair is idiosyncratic within the Germanic-American traditions of the mid-Atlantic region but remains squarely within the shaved chair tradition. The only major difference is the use of extensive sawing for the baluster forms and perhaps the use of rectangular tenons. However, the frame definitely was made with extensive hewing and shaving. By contrast, the frames of most contemporaneous joined seating in the region were sawn from planks.

Another permutation in the shaved chair tradition is represented by the so-called Moses Hall examples from Virgilina, Virginia, which probably represent the work of an African American artisan (fig. 33). These chairs were made circa 1903 to furnish a meetinghall built by a chapter of the Grand United Order of Moses, an African American fraternal society. Despite the progressive social aspirations of the organization, the chairs are conservative, vernacular objects. The maker shaved and burnished the posts and stretchers to make the chairs resemble turned seating. The ears at the tops of the posts may have been influenced by the fully relieved, dramatically bent backs on classic Southern post-and-rung chairs or the ears occasionally found on early-nineteenth-century Windsors.[22]

Antiquarianism and Art in Twentieth-Century Shaved Chairs

The premier expression of late post-and-rung seating in North America is the so-called “settin’ chair” made throughout the American South (fig. 34). A few all-shaved examples are known, but they are rare compared with the characteristic model with turned posts. One of the most accomplished examples was reputedly found in an abandoned cabin in Burnsville, Yancey County, North Carolina (fig. 35). Its rear posts are shaved on their front faces above the seat, radically bent, and set on the bias to allow the maker to set the slats at different angles. The slats are surprisingly ergonomic, supporting the lumbar and thoracic regions of the back.

Because the seats of settin’ chairs are typically level and made of inner bark, they do not provide an ergonomic slope. Although the practice has not been documented, some makers may have trimmed the bottoms of the rear posts to provide layback. Late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographs commonly depict sitters tipping back on the rear legs for comfort.[23]

With the assistance of wood scientist Dr. R. Bruce Hoadley, Alexander discovered the optimal moisture content for all the components of this seating form. In the chair illustrated in figure 36, the technology, lightness, and resilience of shaved post-and-rung construction were pushed to the limits of the medium. Alexander’s classic chair design has also come to symbolize scholarly investigation of traditional green woodworking. As the modern seating illustrated in this article attests, the replication of period technologies offers insights into surviving objects and the people who made and used them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their help in researching and writing this article, the authors thank the late Joyce Alexander, Laszlo Bodo, Johanna Brown, Dennis Carr, Anne Cassidy, Sarah Fayen, Mark Ferguson, Pilar Garro, Henry Glassie, Norman J. Isler, Peter Kenny, Nathaniel Krause, Ethan Lasser, Robert Leath, Abigail Linville, Erin McGough, Susan Newton, Walter Peddle, Deanna Preston, Adrienne Sage, Nancy Sazama, Robert Blair St. George, Harry Mack Truax II, Dante Vallance, John Robert Vincent, Gerald W. R. Ward, and David Wood.

In 2008 John D. Alexander legally changed his gender and his name to Jennie Alexander. For the history of housing and other outbuildings at Plimoth Plantation, see James W. Baker, “As Time Will Serve: The Evolution of Plimoth Plantation’s Recreated Architecture,” Old-Time New England 74, no. 261 (Spring 1996): 48–74.

For more on early woodworking technology, see Herbert Cescinsky, Early English Furniture and Woodwork, 2 vols. (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1922), 1: 17–31, 103–75, 193–210, 231–370, 2: 1–209; Herbert Cescinsky, English Furniture from Gothic to Sheraton (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Dean-Hicks Co., 1929), pp. 1–31, 59–110; Robert Wemyss Symonds, “The Craft of Furniture Making in the XVIth and XVIIth Centuries,” Connoisseur 99, no. 427 (March 1937): 130–37; Robert Wemyss Symonds, “Craft of the Joiner in Medieval England,” Connoisseur 118, no. 501 (September 1946): 17–23 and 118, no. 502 (December 1946): 98–104; and Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture: The British Tradition (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1979).

For more on the technology of post-and-rung chairmaking, see John D. Alexander Jr., Make a Chair from a Tree: An Introduction to Working Green Wood, rev. ed. (1978; Mendham N.J.: Astragal Press, 1994); and John D. Alexander Jr., Make a Chair from a Tree (DVD) (Baltimore: Green Woodworking, 1999). For more on techniques common to both shaved and turned chairs, see Peter Follansbee, “A Seventeenth-Century Carpenter’s Conceit: The Waldo Family Joined Great Chair,” American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998), pp. 197–214. A seventeenth-century reference suggests that turners may have made both shaved chairs and turned chairs. On February 20, 1615, the Turners Company of London “directed that the makers of chairs about the City, who were strangers and foreigners, were to bring . . . [their chairs] to the Hall to be searched according to the ordinances. When they were thus brought and searched, they were to be bought by the Master and Wardens at a price fixed by them, which was 6s per dozen for plain matted chairs and 7s per dozen for turned matted chairs.” A. C. Stanley-Stone, The Worshipful Company of Turners of London: Its Origin and History (London: Lindley-Jones & Brother, 1925), p. 121.

Benno M. Forman, “German Influences in Pennsylvania Furniture,” in Scott T. Swank et al., Arts of the Pennsylvania Germans (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1983), pp. 107–12.

Court cases shed light on trade disputes in seventeenth-century London. In 1633 the court summoned the “Master & Warden of the comp[an]y of Turners” and the “Master & Warden of the Comp[an]y of Joyners” and noted:

It appeareth that the Comp[an]y of Turners be grieved that the Comp[an]y of Joyners assume unto themselves the art of turning to the wrong of the Turners. It appeareth to us that the arts of turning and joining are two several & distinct trades and we conceive it very inconvenient that either of these trades should encroach upon the other and we find that the turners have constantly for the most part turned bed posts & feet of joined stools for the Joyners and of late some Joyners who never used to turn them on bedposts and stool feet have set on work in their houses some poor decayed turners & of them have learned the feate & art of turning which they could not do before. And it appeareth unto us by custom that the art of turning bedposts feet of tables joined stools do properly belong to the trade of a turner and not to the art of a Joyner and whatsoever is done with the foot as have treddle or wheele for turning of any wood we are of the opinion and do find that it properly belongs to the Turners and we find that the Turners ought not to use the [mortising] gage or gages, grouffe [groove] plaine or plough plaine or mortising chisels or any of them for that the same do belong to the Joyners Trade.

Henry Laverock Phillips, Annals of the Worshipful Company of Joiners of the City of London (London: privately printed, 1925), pp. 27–28.

Similarly, a 1632 decision regarding a suit between the joiners and carpenters led to a long and convoluted attempt to separate the two trades. E. B. Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters (London: Pickering & Chatto, 1887), pp. 295–302. Chinnery cited these cases in Oak Furniture, pp. 42–43.

See a brief notice of French royal protection in Pierre Verlet, French Royal Furniture (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1963), pp. 3–7. Before Colbert set up the Garde-meuble system under Louis XIV, French monarchs had offered informal protection and patronage to artists and artisans by housing them in the ground storey of the Louvre. Discussions of guilds in various German cities are found throughout Heinrich Kreisel, Das Kunst des deutschen Möbels: Erster Band von den Anfängen bis zum Hochbarock (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1963).

In 1608 the Turners Company of London instructed:

The Master & Wardens together with so many of the Assistants as they shall appoint shall four times in the year or oftener if necessary at convenient times, enter into the Shops, Sollars, Cellars, Booths and Warehouses of any person using the Misterie who shall make, buy, or sell anything thereunto appertaining within the City or suburbs, either Free or Foreign, there to search & survey all manner of Bushel measures, Wood Wares, Works, and also their Journeymen, Servants & apprentices and all their staffs & workmanship and if in their search they shall find any shovels, scoops, busheltrees, washing bowls, chairs, wheels, pails, trays, truggers, wares, wooden measures or any other commodities belonging to the Misterie slightly or not substantially & workmanlike wrought with good and sound stuff or any other matter of abuse or misdemeanor, either in Master, Mistress, Apprentice, or Servants, it shall be lawful for those making the search, to seize and carry away the same faulty & deceitful wares, into their Common Hall, that the same may be considered & defaced if cause shall appear and the Master, Wardens & Assistants or the greater part of them may assess a reasonable fine upon the offender so as it exceed not 40 shillings for any one offense, so that others may be warned from making or selling deceitful ware to the discredit of the Misterie, and if any whether free or foreign, be found disobedient to the Master Wardens and Assistants or any three of them in any of their searches, he or they shall be fined not exceeding 40 shillings for every offence.

Stanley-Stone, Worshipful Company of Turners, pp. 264–65.

In 1631 London turner Nehemiah Willington bought shovel trees and trenchers that may have been made outside the city. Paul S. Seaver, Wallington’s World: A Puritan Artisan in Seventeenth-Century London (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1985), p. 78. Among earlier-twentieth-century studies that have been influential on later scholars of green woodworking are George Sturt, The Wheelwright’s Shop (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923); Walter Rose, The Village Carpenter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1937); H. Edlin, Woodland Crafts in Britain: An Account of the Traditional Uses of Trees and Timbers in the British Countryside (London: B. T. Batsford, 1949); and J. Geraint Jenkins, Traditional Country Craftsmen (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965). More recent monographs include Anton Viires, Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey (Jerusalem: Israel Program for Scientific Research, 1969); Fred Lambert, Tools and Devices for Coppice Crafts (Powys, Wales: Centre for Alternative Technology, 1977); Charles F. Hummel, With Hammer in Hand: The Dominy Craftsmen of East Hampton, New York (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1968); Raymond Tabor, Traditional Woodland Crafts (London: B. T. Batsford, 1994); Cecil A. Hewett, The Development of Carpentry, 1200–1700: An Essex Study (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1969); Cecil A. Hewett, English Historic Carpentry (London: Phillimore & Co., 1980); W. L. Goodman, The History of Woodworking Tools (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1964); and Robert Tarule, The Artisan of Ipswich: Craftsmanship and Community in Colonial New England (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004).

The literature of the American “settin’ chair” is discussed in n. 23 below. The various Canadian shaved chairs are discussed in Jean Palardy, Les meubles anciens du Canada français (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1963), nos. 280, 281, 283–91, 306, 318, 319, 323, 324, 326–29, 343–47, 352, 355, 361; W. John McIntyre, “Chairs and Chairmaking in Upper Canada” (master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 1975), pp. 100–101; Walter W. Peddle, The Traditional Furniture of Outport Newfoundland (St. Johns, Newfoundland: Henry Cuff Publishers, 1983); Michael S. Bird, Canadian Country Furniture, 1675–1950 (Toronto: Stoddart Publishing Co., 1994), p. 38, fig. 11; p. 153, figs. 159, 161; p. 179, figs. 223, 224; p. 180, fig. 226; p. 272, fig. 450; p. 292, fig. 493; p. 307, fig. 521; p. 335, fig. 589; Donald Blake Webster, Rococo to Rustique: Early French-Canadian Furniture in the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 2000), pp. 177–99; and Michel Lessand, Antique Furniture of Québec: Four Centuries of Furniture Making (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2002), pp. 126–35. Northern European visual sources consulted include Lilian M. C. Randall, Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966); Linda A. Stone-Ferrier, Dutch Prints of Daily Life: Mirrors of Life or Masks of Morals? (Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1983), p. 57, cat. no. 6; p. 65, cat. no. 9; p. 125, cat. no. 30; Christopher Brown, Images of a Golden Past: Dutch Genre Painting of the 17th Century (New York: Abbeville Press, 1984), pp. 69 and 74; Peter C. Sutton, Masters of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Genre Painting (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984), p. 327, pl. 47, cat. no. 111; p. 355, pl. 48, cat. no. 124; Wayne E. Franits, Paragons of Virtue: Women and Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 49, fig. 31b; p. 189, fig. 168; Michiel C. C. Kersten and Danielle H. A. C. Lokin, Delft Masters, Vermeer’s Contemporaries: Illusion through the Conquest of Light and Space (Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 1996), p. 165; Jan Steen: Painter and Storyteller, edited by Guido M. C. Jansen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996); Eddy de Jong and Ger Luitjen, Mirror of Everyday Life: Genre Prints in the Netherlands, 1550–1700 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1997); Peter C. Sutton, Pieter de Hooch, 1629–1684 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998); Gerrit Dou, 1613–1675: Master Painter in the Age of Rembrandt, edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000); Henk van Os, Jan Piet Filedt Kok, Ger Luijten, and Frits Scholten, Netherlandish Art, 1400–1600 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2000), p. 267; C. Willemijn Fock et al., Het nederlandse interieur in beeld, 1600–1900 (Zwolle: Waanders, 2001), pp. 143, 152; Mariët Westerman et al., Art and Home: Dutch Interiors in the Age of Rembrandt (Denver: Denver Art Museum; Newark, N.J.: Newark Museum, 2001), pp. 33, 49, 58, 69, 99, 108, 125, 140; Wayne Franits, Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Senses and Sins: Dutch Painters of Daily Life in the Seventeenth Century, edited by Joroen Giltaij (Rotterdam: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2005), pp. 98, 105, 113, and 185.

Irving P. Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” Antiques 20, no. 4 (October 1931): 210–16.

Peter Thornton, The Italian Renaissance Interior, 1400–1600 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991); At Home in Renaissance Italy, edited by Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2006); Dora Thornton, The Scholar in His Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997); and Elizabeth Currie, Inside the Renaissance House (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2006). Peter Thornton consistently refers to shaved chairs as “rustic,” but the uniformity and occasional elaboration of the Italian chairs across many urban centers suggest that they were a professional urban product.

Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” pp. 210–16, fig. 4. Richard C. Nylander et al., Beauport: The Sleeper-McCann House (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1990), pp. 38–46.

The Rochester chair belonged to Irving P. Lyon and is discussed in Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” pp. 210–11, fig. 1.

The Thompson chair is discussed in ibid., pp. 210–11, fig. 2; and The Concord Museum: Decorative Arts from a New England Collection, edited by David F. Wood (Concord, Mass.: Concord Museum, 1996), p. 58, no. 23. Caqueteuse chairs are discussed in Peter Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), pp. 186–87; and Chinnery, Oak Furniture, pp. 242, 244, 245, 451–54, 461–67.

The Wayland chair is discussed in Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” p. 211, fig. 3.

The authors thank Peter Kenny for bringing the Senate House armchair to their attention. A New York slat-back armchair with convex ends on the shaved arms is on loan to the Walt Whitman House in Hempstead, New York, from the New York State Department of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (1974.26). The writers thank Erik Gronning for bringing that chair to their attention. Gronning is preparing a major study of New York slat-back chairs in the Dutch tradition.

Brian Cullity, “A Cubberd, four joyne stools & other smalle thinges”: The Material Culture of Plymouth Colony and Silver and Silversmiths of Plymouth, Cape Cod and Nantucket (Sandwich, Mass.: Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, 1994), p. 121, figs. 127, 128.

Accession file 2004.13, Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Lonn Taylor and Dessa Bokides, New Mexican Furniture, 1600–1900: The Origins, Survival, and Revival of Furniture Making in the Hispanic Southwest (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1987).

Chairs with scalloped top edges to the crest rails and turned arms first appear in various regional centers circa 1810–1820. Mid-eighteenth-century banister-back and slat-back chairs associated with Massachusetts and New York also have scalloped upper edges with central cusps on the crests or slats. Shaved and bent posts first appear in Windsors circa 1805–1810 and were transferred to post-and-rung chairs somewhat later. For more on these developments, see Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs (Winterthur, Del.: Winterthur Museum, 1996). For more on the Keels chair, see Walter Peddle, The Dynamics of Outport Furniture Design: Adaptation and Culture (Gatineau, Québec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, History Division, 2002), p. 10.

Lyon, “Square-Post Slat-Back Chairs,” fig. 30.

This chair was purchased in New England and has no provenance.

Research by Abigail Linville of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, suggests that the Moses Hall chairs date from the early twentieth century. See also Holly Hope, For the Memorable Fight: Mosaic Templars of America Headquarters Building (Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 2004). Robert Pottage of Halifax, Virginia, brought the chairs to the attention of Robert F. Trent in the late 1970s. Trent donated examples to Winterthur Museum and the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in 1990.

Literature on the American settin’ chair is sparse. The earliest recognition of the form was Allen H. Eaton, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1937), pp. 147–61 and figs. opp. pp. 93, 197, 200. Eaton’s interviews and questionnaires established that Appalachian chairmakers employed riving, shaving, heating and bending of posts and slats, and assembly with dry rungs driven into wet posts. Another source with technical information is “An Old Chairmaker Shows How,” Foxfire 1 (1969): 128–38. Modern academic studies include John Robert Vincent, “A Study of Ozark Woodworking Industries” (master’s thesis, University of Missouri at Columbia, 1962); Henry Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), pp. 230, 231, fig. 66; Michael Owen Jones, “Chairmaking in Appalachia: A Study in Style and Creative Imagination in American Folk Art” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1970); Michael Owen Jones, The Hand Made Object and Its Maker (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975); Michael Owen Jones, Craftsman of the Cumberlands:Tradition and Creativity (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1989); and Warren E. Roberts, “Turpin Chairs and the Turpin Family: Chairmaking in Southern Indiana,” Midwestern Journal of Language and Folklore 7, no. 2 (Fall 1981): 55–106.