Ranelagh masquerader figures, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, gold anchor period, 1759–1763. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 8 1/2". Mark, on seven of the eleven figures: gold anchor. (Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The eleven masqueraders shown here are displayed on the mantel of the Dining Room at the Governor’s Palace, Colonial Williamsburg.

Jack O’Green and Mate, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, gold anchor period, 1759–1763. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 8". Marks: gold anchor on Jack; impressed “M” on mate. This is the only natural pair among the Ranelagh masqueraders.

The Four Continents, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, patch mark period, ca. 1760. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 12 3/4". Marks: None.

The opening dinner of the ninth Summit of Industrialized Nations, Supper Room, Governor’s Palace, Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, 1983. President Reagan is shown at the center, with The Four Continents illustrated in fig. 3 ornamenting the table in front of him.

Monkey band figures, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, red anchor period, ca. 1756. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 8". Mark, on seven of the ten: red anchor.

Monkey band figures, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, red anchor period, ca. 1756. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 5 3/4".

Dressing box, American China Manufactory (Bonnin and Morris), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 4".

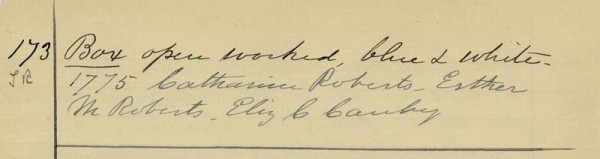

Entry of the dressing box illustrated in fig. 7, in the “Catalogue of China” compiled by Elizabeth Clifford Morris Canby in the nineteenth century, in which the basket is described as a “Box open worked.”

Tea and coffee service, Worcester Porcelain Manufactory, Worcester, England, 1765–1775. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of coffee pot 9 1/8".

Four milk jugs, Worcester Porcelain Manufactory, Worcester, England, 1750–1755. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest 3 1/4".

Tureen, cover and stand, and soup plates, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, gold anchor period, 1762–1763. Soft-paste porcelain. L. of tureen 13". Mark, on all: gold anchor. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum and Garden, Gift of the Campbell Soup Company.) These objects are from the Mecklenburg-Strelitz service.

Soup plate, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, gold anchor period, 1762–1763. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 9 3/8". This plate is from the Mecklenburg-Streliz service.

Pair of vases, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, raised anchor period, 1750–1752. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 9 1/8".

Objects with prunus decoration: Beaker, Dehua, China, 1700–1740. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 3". Beaker, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, raised anchor period, 1750–1752. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 3 1/8". Plate, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, raised anchor period, 1750–1752. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/4". Cup, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, Meissen, Germany, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 1 3/8". Two cups and one saucer, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, ca. 1755. Soft-paste porcelain. H. of tallest cup 2 3/8". D. of saucer 4 5/8".

Tureen and cover, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, ca. 1755. Soft-paste porcelain. L. 13".

Interior of the tureen illustrated in fig. 15.

Britannia Mourning the Death of the Prince of Wales, Vauxhall Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, 1751–1752. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 11 1/4". Plate, Vauxhall Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, 1750–1760. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 8 3/4".

Details of the figure and plate illustrated in fig. 17.

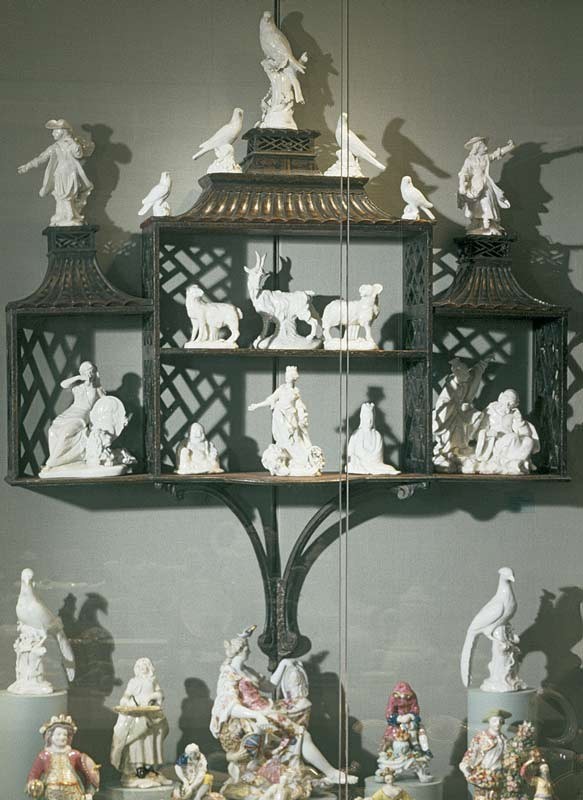

Bracket shelf dressed with English soft-paste porcelain figures, English porcelain installation at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg: Finch, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, triangle period, 1745–1749. H. 7 3/4". Grape gatherers, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1755. H. of tallest 7". Small birds, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, raised anchor period, 1750–1752. H. 2 3/4". Large birds, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1755. H. 4 1/8". Goat, ewe, and ram, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1755. H. of tallest 6 1/2". Pu-tai Ho-shang, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, triangle period, 1750–1752. H. 3 1/4". Britannia, Earth, and Europa, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1755. H. 6 7/8". Kuan Yin, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, London, England, raised anchor period, 1750–1752. H. 4 1/2". Britannia, Gouyn Factory, London, England, 1751–1753. H. 7 3/4". Group of Chinese figures, Derby Porcelain Manufactory, Derbyshire, England, ca. 1755. H. of tallest 7 7/8".

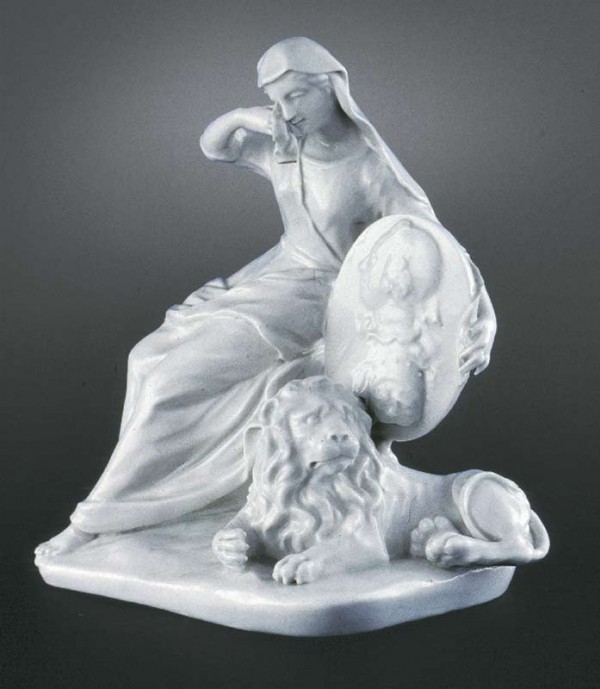

Britannia, Gouyn Factory, London, England, 1751–1753. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 7 3/4".

Typical of many—if not most—curators, I, as Curator of Ceramics and Glass at Colonial Williamsburg, am guilty of not being well rounded in my choice of the ceramic objects I encouraged the foundation to add to its collections. I urged Colonial Williamsburg to expand its holdings of Chelsea porcelain and British “delft” or delftware. The delft collection, of which we already had an excellent beginning, is now one of the most important in the world.[1]

Shortly after I arrived, Colonial Williamsburg acquired the M. G. Kaufman collection of English porcelain, which for the most part included important examples of Chelsea—primarily from the two earliest periods, the triangle and raised anchor. Colonial Williamsburg had been adding examples of the later periods before my arrival and continued thereafter.[2]

In addition to these two types of ware, I was constantly on the lookout, especially during the second half of my tenure, for objects that had reason for being in Williamsburg’s colonial exhibition buildings—eighteenth-century objects that were mentioned in local inventories, advertisements in the Virginia Gazette, and merchant orders from England. Of course, I sought out objects that were matches for our large and ever-growing collection of archaeological sherds under the guidance of resident archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume.

I knew little about ceramics when I interviewed for a job as a general cataloger at Colonial Williamsburg in 1959. I admit that I lied when asked if I knew “all about salt glaze.” I did know something, as I had taken courses on ceramics at night and during the day was a student at the Courtauld Institute of the University of London, with Peter Ward Jackson, keeper of Prints and Maps at the V&A, as my tutor. I did my paper on William Vile, cabinetmaker to George III. After I was hired, I learned from Colonial Williamsburg’s great collections. Our job as catalogers (there were three of us) was to go into an exhibition room and catalog everything in it. One might start cataloging a table, the candlestick on the table, the looking glass or painting over the table, and so forth. Eventually we got tired of fighting over the same reference books and decided to specialize. I happened to be cataloging a delft punch bowl at that moment, so I chose “ceramics.” That was the beginning of a lifelong passion.

John Meredith Graham was THE curator. He had a good eye and a great passion for ceramics and, with Rockefeller money and the freedom to buy what he wished, was able to build a large, though unorganized, collection of antiques, a large part of which was ceramics. Eventually, I was given the title Curator of Ceramics and Glass, becoming the first specialist curator at Colonial Williamsburg.

Working for ten years under Mr. Graham, an avid colonial revivalist, I learned to enjoy ceramics mainly for their aesthetic value, but when Graham Hood arrived in 1971, my world was turned around. Ceramics, though always appreciated for their beauty or simple lines, became important for their place in Williamsburg’s history as the colonial capital of Virginia. Before Graham Hood’s arrival, I had not looked at an inventory and was discouraged from examining archaeological sherds, but now a new and exciting world opened to me.

Two events, both of which occurred while I worked under Graham Hood, stand out as by far the most memorable and meaningful in my professional life. The first was the refurnishing of the Governor’s Palace, which spurred my interest in researching social history.[3] The 1770 inventory of the Governor’s Palace after the death of Governor Lord Botetourt listed many pieces of ceramic, not only “china” but “English China” and, most exciting, “Chelsea China.”

The second event was the construction of the Wallace Gallery in 1989, which gave me the opportunity to exhibit many important pieces as works of art that heretofore were shown, if at all, only as furnishings in cupboards of the exhibition buildings. The installation of the ceramic galleries in what is now known as the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum cemented my love for the decorative arts. For the first time, most of the pieces of Chelsea in the Kaufman collection could be seen and studied. Two recently received Worcester porcelain collections, one given by Sam and Polly Clark, the other by Mrs. Owen Coon, were also able to be seen and studied up close.

Masqueraders in the Governor’s Palace

Working with Graham Hood in refurbishing the Governor’s Palace guided by what eighteenth-century documents that we had, I had the opportunity to use Chelsea porcelain in an exhibition building. Among the “China” and “English China” listed in the 1770 inventory of the estate of Governor Botetourt are two sets of “11 Chelsea China figures,” one in the “Front Parlour” and the other in the “Dining Room.” The other china objects in the dining room were listed as being in a “bowfat” or china cupboard. Since the dining tables appear, in eighteenth-century fashion, to have been folded and against the wall, we assumed that the listed figures had to be on the mantel. This assumption was strengthened by the fact that in the inventory the “11 Chelsea China figures” are listed right after the fireplace equipment and the fire screen.

The masqueraders (fig. 1) were a good choice for the dining room’s mantel. These festive figures are believed to represent guests who attended the masquerade ball in 1759 at Ranelagh Gardens in London for the birthday of the Prince of Wales, who became George III the following year; Lord Botetourt could well have attended. Exactly how many figures were in the set, if, indeed, it was intended to be a set, is unclear; fourteen has been suggested by some authorities. Although Williamsburg purchased thirteen from one source, they have different histories, having only some of their former collections in common. Two in the group were duplicates, leaving the eleven different models.

Jack O’Green and his mate are the only ones that unquestionably were designed as a pair (fig. 2). They have a slightly different feel, and were it not that the female figure wears a mask, one might question if they were people masquerading at all and not just an earlier version of Mozart’s Papageno and Papagena or other characters in folklore. A single example of the female survives and a pair has recently been recorded.[4]

During the period of the refurbishing we also were able to add a number of figures of birds copied at Chelsea after engravings by John Edwards. We used these figures to make up the second set of eleven to place on the mantel in the parlor. Again, the choice of subject was consistent with Lord Botetourt’s fascination with natural history, and, according to his accounts, he had actually purchased local birds to send back to England.

The Four Continents

Toward the end of May 1983 the ninth annual Summit of Industrialized Nations—Canada, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, West Germany, and a representative from the European Commission—was held in Williamsburg, Virginia. Each of Colonial Williamsburg’s major exhibition buildings was the site for at least one event. As Graham Hood was on sabbatical, I, as acting Director of Collections, got to divvy up the responsibilities among the curators. I saved for myself the Governor’s Palace, where the opening dinner was to be served. Only heads of government were invited to attend that affair.

From the very beginning there was friction within the ranks. The men of the State Department, which traditionally controlled such setups, were at loggerheads with the “First Decorator,” a very close friend of President Reagan and Mrs. Reagan who, as their interior designer, had been given responsibility by the president to make sure the settings were up to their standards. For the most part I kept my mouth shut, although I did mediate on two occasions. The first involved what to put on the table for decoration. I suggested placing along the long table the magnificent Derby porcelain figures representing the four continents (fig. 3). All thought that was a great idea, and it was decided, after multiple rearrangements, that “America” should face President Reagan.

The second mediation had to do with lighting. The First Decorator wanted to place candelabra in front of the two windows, as the reflection of the candlelight on the glass would give a pleasant effect. Since the plan was to let in a horde of photographers after the dignitaries were seated, however, the State Department men said no, reasoning that the glare of the windows would ruin the shots (fig. 4). So the great moderator stepped in and suggested that a costumed custodian be allowed in, before the photographers started taking pictures, to pull down the spring blinds in the very high windows and return them to their normal position when the photographers were finished. The suggestion was accepted by both sides.

When the dignitaries were seated and the photographers about to be let in, however, the costumed custodian walked over to the window, as planned. Unfortunately, the custodian turned out to be too short to reach the shades. So, trying to remain invisible, I pulled the shades down myself. No problem; no one noticed me. When it was time to let the shades up again, I quietly let the first shade up to its usual position and walked over to the second to raise it. As I reached for it, it slipped out of my hand. Rattle, rattle, rattle! The shade made such a noise as it clattered all the way to the top of the window. I was embarrassed when all the heads of government turned to look at me, but when the Secret Service started to pull their guns, I was more than just embarrassed.

Historically, people liked things to be in sets of four, from the four seasons to the four suits in a deck of cards. Even before it was known that there was another continent, let alone two, beyond the great sea, it was commonly accepted that there were four parts of the world. The discovery of the Americas made the division more logical as they also represented North, Europe; South, Africa; East, Asia; and West, America. From the sixteenth century through Victorian times, prints, drawings, statues, to the finest of European porcelain, the continents were depicted, each represented by a man or a woman surrounded by appropriate symbols, many commonly used.

An animal is usually included in representations of each of the continents, but Europe’s horse was excluded from this set. For the other three continents, however, the camel, lion, and alligator figures were appropriately employed albeit designed by someone who had little idea of the appearance of the animal he was depicting. Placed all around the base of Europa, including the back, were emblems of the arts—music, painting, and architecture, the church (bishop’s miter), literature (books), justice (the gavel), plenty (cornucopia), and war/peace (helmet). The horse was excluded simply because there was not enough room. On the other hand, the porcelain designers were so short of emblems for Asia that they elongated the camel to fill the back. Almost universally, each representation of a continent has an elaborately symbolic headdress: a crown on the head of Europe, a feathered “warbonnet” on America, a wreath of fruit or flowers on Asia, and the ridiculous elephant hat on Africa.

Monkey Band, 10 + 2

The Chelsea monkey band figures are larger copies of Meissen hard-paste porcelain, in this instance first modeled by J. J. Kaendler in 1753. Meissen originally produced nineteen different figures based on watercolor drawings dated that year by Christophe Huet, but continued to add more to the assemblage through the years.[5] In England, monkey band figures were produced at Bow, Chelsea, Derby, and Rockingham. They were also produced in earthenware and porcelain in other European countries throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In the mid-1750s the factory at Chelsea sold their ware at auction. The two earliest sales were in 1754, but no catalog from them appears to have survived. In the earliest surviving sale catalog, of 1755, there is no listing for the monkey band figures.[6] In the 1756 sale catalog, however, they are listed eleven times as either “A set of 5 musical figures representing monkies in different attitudes” or “A beautiful set of 5 monkies in different attitudes playing on music.”[7]

In 1977, when I was doing research for my book Chelsea Porcelain at Williamsburg, only ten of the Meissen figures were thought to have been copied at Chelsea, and each was represented in the collections at Williamsburg (fig. 5). As all the listings in the 1756 catalog were for sets of five, one was tempted to conclude that Williamsburg’s ten were two sets. If a customer wanted all ten, he would merely purchase both sets.

After I checked the color on my book and the presses began to roll, I returned from Richmond to find on my desk the latest Sotheby’s catalog. As I thumbed through it, I discovered with a mixture of delight and dismay that lot 222 was for a Chelsea monkey band figure playing a guitar—it was not one of the ten, but in fact an eleventh! (You know the old saying, “the ink is not even dry when new information....”) I argued to the accessions committee that if Colonial Williamsburg had all ten known monkey band figures, it would be only logical to have all eleven. The committee agreed. I found a donor and we were the high bidders, thus giving Williamsburg all eleven known Chelsea monkey band figures.

Another example listed in the sales catalog, a female singer described as a duplicate of one at the Victoria & Albert Museum, which I knew well, was also a duplicate of one at Williamsburg. We didn’t need a duplicate, so, to prevent any seeming conflict of interest, I petitioned and received permission to bid on it for myself, which I somehow achieved at an affordable price. When the figure eventually arrived, I unwrapped it and discovered that it was not a duplicate. It was, in fact, a twelfth monkey band figure, a version of the female singer with her mouth closed. She was in my collection for less than a week—if Colonial Williamsburg needed all eleven known monkey band figures, it certainly needed all twelve (fig. 6).

Bonnin & Morris Dressing Box

I was sitting in the Virginia Room during the 1968 Williamsburg Antiques Forum, listening to Graham Hood talk about the American China Manufactory of Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris, considered to be the first to successfully produce porcelain in what is now the United States. Graham had just published the first detailed account of this factory, gathering most of his information from archaeological sherds at the factory site and what written material was available.[8] Three years later he became chief curator at Colonial Williamsburg and my boss and mentor.

Sitting next to me in the audience was Mrs. Rose Rumford, whom I knew only as the mother of my colleague Trix Rumford. At some point during the lecture, Mrs. Rumford leaned over to me and said, “John, we have an old piece of Worcester at home, with that funny ‘P’ mark.” She later asked if we wanted to see it, and subsequently she produced an old notebook in which its history was recorded. The following year Mr. and Mrs. Rumford presented the object to Colonial Williamsburg (figs. 7, 8). In a letter dated 1988, their daughter Trix Rumford wrote:

Mrs. Elizabeth Rumford, in the 1880s a “catalogue of china” which was compiled of information on ceramics and other objects which she had inherited or purchased. Number 173 reads “Box open worked, blue & white. 1775 Catherine Roberts, Esther M. Roberts, Eliz. C. Canby.” Catherine Deshler who married Robert Roberts in Philadelphia in 1775 was apparently the first owner. Ester Morton Roberts was their daughter and Elizabeth Clifford Morris Canby their grand daughter-in-law. She also was the mother Elizabeth Rumford who recorded the box, and the great grandmother of Lewis Rumford II who presented it to Colonial Williamsburg.

In 2009 Trix presented to Colonial Williamsburg more than one hundred additional pieces that are listed in the Rumford family catalog, the ceramics consisting of mainly Chinese export porcelain dating from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In 1970 a group of ten of us, mostly museum curators, had formed an association for the study of ceramics of all periods and provenances. The American Ceramic Circle, as it was called, now boasts approximately five hundred members and meets at a different, usually American, museum every fall.[9] We asked Graham to be the keynote speaker at the first seminar of the association to discuss the Bonnin and Morris factory, as it was appropriate that the first lecture be on an American subject. We published his lecture in our first American Ceramic Circle Bulletin, now called the American Ceramic Circle Journal.[10] He noted that his address was given on the two-hundredth anniversary of the founding of the short-lived factory in Philadelphia.[11] In the 2007 issue of Ceramics in America, Graham’s book Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia was reprinted and updated, coinciding with a landmark exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in which all nineteen examples of Bonnin and Morris known at that time were reunited.

Worcester Porcelain Collections

How is it possible that two collections of Dr. Wall–period Worcester porcelain could be formed at the same time, both in greater Chicago, each containing nearly or more than three hundred examples, each donated to Colonial Williamsburg about the same time, and yet have only one duplicate in form and decoration? In many ways both collectors also became good friends of Williamsburg and, more important to me, became good friends of mine. One reason for the diversity is that they approached their collecting with different goals and searched in different geographic areas.

Louise Coon (Mrs. Owen Coon) worked with a couple of English dealers who knew what she liked and offered her special objects, although she was very selective and in no way jumped at everything offered her. She also acquired many of her pieces from Marshall Fields—yes, the large Chicago department store—which at one time had a first-rate antiques department and a buyer who really knew her Worcester porcelain.

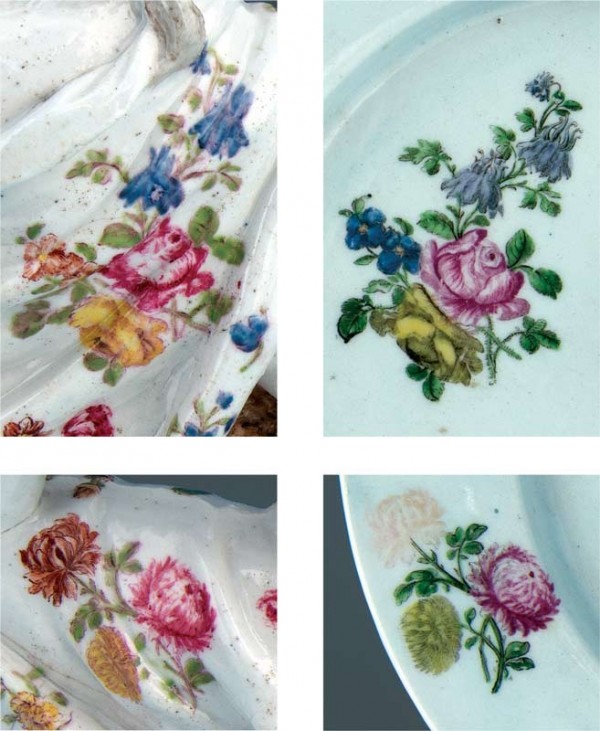

Louise Coon’s interest was not necessarily in a particular form or decoration but more in how the different forms and designs worked together and enhanced one another, exemplified by the tea and coffee service pictured in figure 9. This wonderful, nearly complete service is molded with the so-called Warmstry flutes and decorated with the Oriental Quail pattern, which probably reached Worcester via the Continent rather than coming directly from China.[12] Thanks to Mrs. Coon, her son Harry and his wife, Alma, also became great friends of Williamsburg, enriching it not only financially but also by passing on some of their own collections, filling gaps in areas that had been neglected.

Sam and Polly Clarke were dear friends of mine and my wife as well as of Colonial Williamsburg. Sam was the primary collector in the family, but feisty Polly would certainly make her opinion be heard. Unlike Louise Coon, Sam collected by category. Not only did he want one example of each variation of each form, but each piece had to be of top quality, as exemplified by four milk jugs from the early period of Worcester (fig. 10). They illustrate examples with both fluted and bas-relief molded shapes. In 1987 Sam and I produced a small book, Worcester Porcelain in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection.[13] We worked together to choose the objects—Sam wrote the text and I prepared a contextual overview on English porcelain. The selected objects included examples from the Coon and the Clarke collections, plus examples from a smaller collection of blue-and-white Worcester, given to Colonial Williamsburg by Mr. and Mrs. John A. Williamson about the same time. Sam and Polly Clarke left their estate to Colonial Williamsburg, which precipitated a named position in their honor.

Mecklenburg Service

When the Campbell Soup Company decided to produce a catalog of its collection of soup equipage, I was asked to prepare the ceramics section. I was really out of my element, having never worked with Continental pottery and porcelain, but somehow I managed to produce three editions, with, I hope, a minimum of errors.[14] They were intended to be catalogs to accompany the various exhibitions of the collection in museums across the country and abroad. Displays in France and Japan necessitated that the catalogs be translated into those languages. A proper catalog, with much greater detail, was published in 2000 upon the donation of the Campbell collection to the Winterthur Museum.[15]

I was delighted when the Chelsea Mecklenburg-Strelitz tureen, stand, and soup plates (fig. 11) arrived at the Campbell Soup Company in Newark, New Jersey, as I had seen the greater part of it when I visited Buckingham Palace as a student in 1958–59. On that occasion I had gone to the headmaster, Sir Anthony Blunt, and said I would like to go to Buckingham Palace to see some furniture belonging to the queen for my paper. I was told that since I was an American, it could be arranged. At Buckingham Palace I was accompanied by the Keeper of the Queen’s Pictures, with whom I had taken a class. We did little looking at furniture but instead toured the back rooms and the grand rooms within the palace. The last room was the Throne Room, which was being used as a storeroom, and that is where I saw, on either side of the throne (which was covered with a drop cloth), large glass cases filled with the massive, magnificent Mecklenburg-Strelitz dinner and tea service. It contained many forms in addition to several sizes of tureens: bowls, plates, sauceboats, salts, and even a few candelabra—137 pieces altogether. It was most impressive, even to the young man who at the time was studying to be an English furniture scholar. (Now I wish I had spent more time studying it, but then it was “only porcelain.”)

The service was produced at the Chelsea manufactory in 1762–1763 by order of George III for Queen Charlotte’s brother Adolphus Frederick IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. It was in two different collections by 1947, when it was presented to Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wife of King George VI. The late “Queen Mum” was fond of mid-eighteenth-century porcelain and had an important collection of mostly Botanical Chelsea.

The tureen and other Mecklenburg-Strelitz pieces, such as the soup plate in Colonial Williamsburg (fig. 12), are believed to have been separated from the collection for several years before they were reunited and presented to the Queen Mother. The Winterthur Mecklenburg tureen from the Campbell collection appears to be identical to ones still part of the service, except there are disheveled-looking birds painted on the cover in place of swags.

I became very excited when a soup plate from the Mecklenburg service became available on the market at the same time that Carolyn Maness, a friend of mine and of Colonial Williamsburg, was looking for a gift in honor of her parents. Knowing of her love for porcelain, I thought the soup plate would be a perfect choice. I was so pleased when she agreed, and my long desire to have an example from the Mecklenburg service in the collections at Colonial Williamsburg was fulfilled.

The exotic and disheveled birds that appear on every piece in the service were very popular on Chelsea in both the red- and gold-anchor periods and can be found on wares of other English factories. They often are referred to as “Giles birds,” in reference to James Giles, who had an independent decorating studio in London. Although there is little doubt that James Giles did paint some of the birds, we know he directed a fleet of decorators of various skills working in his studio.

Prunus Decoration

I was drawn to prunus decoration partly due to the resemblance to the cherry blossoms that every spring adorn our nation’s capital, but I was confused by the name, which, of course, is Latin for plum. I checked Google, now my first attempt at research, and found the term comprises no fewer than 430 species, among them not just plums but also almonds, apricots, cherries, and nectarines.

The simplicity of the design when used in relief makes it perfect to show off porcelain left “in-the-white.” The pair of Chelsea vases illustrated in figure 13 are in a form which in England would have been molded, whereas the Chinese prototype, if there was one, would have been mottled and the decoration sprigged on, that is, applied by hand. The decoration on the two vases is identical, so the decoration must have been part of the mold; the pieces that appear to be thrown on a wheel would have had the decoration applied.

Based on surviving pieces I have been able to discover, I believe that the Chelsea factory made only a few forms in the prunus design and mostly on oriental shapes (fig. 14). The Chinese beaker shown here (left) is identical to the Chelsea example (right). A rare prunus-decorated plate is of what might be considered a European shape. The decoration on the plate, of which only about four have been recorded, is in lower relief than the vase and beakers and therefore is definitely molded, not sprigged. Chelsea’s “teaplant” tea service of a few years earlier is similar to the prunus pieces but comes in European tea- and coffeeware shapes. This suggests to me that Nicholas Sprimont, manager of the factory, made a point to keep the prunus design as seen in the Chinese examples.

Bow, on the other hand, produced full or partial tea and dinner services with raised prunus decoration. Surviving along with Colonial Williamsburg’s teacup and saucer are plates and platters in various sizes and a glorious soup tureen in the Campbell collection at Winterthur.[16] The one Continental piece illustrated here, the Meissen cup in Colonial Williamsburg, is included to remind us that the raised prunus design was also used throughout Europe. Thanks to the two beakers, however, it is clear that the raised prunus design came to England, or at least to the Chelsea factory, directly from the Orient rather than via the Continent, which we believe is true of most of the oriental decoration in eighteenth-century pottery and porcelain.

Bow Leaf Tureen

I selected this leaf-molded tureen for two reasons: its exterior (fig. 15) and its interior (fig. 16).

The inspiration of nature can be seen in all forms of art. Most painting evokes nature—landscapes, still lifes, and even portraits when a lady has a rose pinned to her bosom. Sculpture, though rarely depicting nature in itself, is most glorious in natural surroundings, thus becoming part of nature. Let’s consider music. I recall once sitting on the lawn at Berkeley Plantation overlooking the James River, listening to the Virginia Symphony play Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. As the orchestra drums signified an impending thunderstorm in the Summer segment, a real thunderstorm could be heard approaching. The two thunder sources started echoing one another. Everyone was so entranced by the counterplay that the possibility of an eventual downpour was not even considered. That, to me, epitomizes nature in music. I may be showing my prejudice when I say that ceramics, particularly porcelain, express nature most of all.

It was the genius of the eighteenth-century potters who put nature on the dining table by designing their tureens and sauceboats in the shapes of animals or fruit. These potters also drew from botanical prints for the dining plates, to unite the natural theme of the whole ensemble. I am most inspired by the way the leaf was utilized.

In my retirement, I spend every moment the weather permits in my gardens. My “shade garden” consists mainly of many types of ferns and hostas. In these plants, the leaf is the reason for being; the flower, if there is one, is incidental. The leaf form in ceramic material is either shown individually, as though having fallen onto the table from a tree, or in clusters of overlapping leaves to form a useful shape, as in this tureen.

The charming painting on the interior is of the garden in which the leaves on the exterior must have grown. That is what unites the exterior and interior. The classical ruins remind us that nature and natural beauty have been with us forever.

The design for the unusually shaped fountain may well have come from a print by Gabriel Pérelle, published before 1663. A recent article in the American Ceramic Circle Journal shows the print along with a series of Giles-decorated Worcester plates depicting classical ruins.[17] The three columns to its right appear to represent the Temple of Castor (or Peace) in the Forum at Rome; at the same angle, they appear on Worcester examples of Hancock transfer prints.[18]

For those who wonder why anyone would put a painting on the interior of a tureen, my reply would be to “imagine the effect of looking into the tureen filled with simmering almost-but-not-quite-clear broth. The garden would surely come alive.”

Vauxhall Britannia Figure and Plate

As more research is done, through written documents and archaeology, it is apparent that ceramics scholars are not only able to be more accurate or assured in their attributions, they are also able to ascribe wares more closely than before. For instance, many pieces of both pottery and porcelain that were known only to have been made in Liverpool can now be given to a particular factory in that city. We see this, for example, in a recent article by Rod Jellicoe, in which he presents new Liverpool attributions for figures previously thought to have been made in other areas.[19]

The plate illustrated in figure 17 right had for many years been believed to have been made in Liverpool, as it had many of what were believed to be “Liverpool features.” The Vauxhall-made figure of Britannia (figs. 17 left, 18 left) was, in my day, thought to have been made at Longton Hall, in Staffordshire, based on the paste. The noted authority Dr. Bernard Watney in his 1957 book on the Longton Hall factory illustrated an example, mentioning that it was decorated in Liverpool.[20] Even though the switch to London—based, again, on archaeology—has been recent, its attribution to Longton Hall must have been questioned for some time. In preparing the present article, I found in the Williamsburg files a note I made in 1973 when I showed the figure to Dr. Watney. I quoted him as saying, “This figure could turn out to be Liverpool instead of Longton Hall. It has many of the Liverpool attributions and of course the Liverpool transfer printing.” These attributions are now considered to be Vauxhall. According to a 1989 English Ceramic Circle Transactions article written by Dr. Watney, by that time, due to new archaeological finds, he believed that the plate had been made in Vauxhall.[21] He heads one section “How Did the Vauxhall Factory Come to Decorate Longton Hall Porcelain?” He illustrates the two details of these pieces shown here.[22] This was written when only “trial excavations” had been completed. He was anticipating more digs “so that so much more can be learned about the output of this factory, in particular, their production of figures.” This suggests to me that Dr. Watney suspected the figure might very well have been made at Vauxhall and was looking for proof.

Another question about the transfer prints was whether they were polychrome printed or monochrome prints that were enhanced by hand painting. The development of a transfer that could print more than one color at a time was just beginning to come into its own. In the details of the two pieces shown here, one can see an identical transfer on both. We can tell that these are hand-painted overprints, because the center blossom on one is left unpainted, showing only the monochrome print.

Hanging Shelf

A pair of English wooden shelves in the Chinese taste hung on opposite walls of the Supper Room in the Governor’s Palace from the earliest days of the restoration. When I came to Williamsburg, one shelf was filled with the Chelsea monkey band, the other housed later porcelain and earthenware. About 1964, John Graham thought we might decorate the second shelf with the wonderful collection of white, mid-century English porcelain he was acquiring. Even though they might be considered the “56 pieces of ‘ornamental China’” listed in Lord Botetourt’s inventory, correctness was not a consideration. They were just meant to be attractive, which I thought they were. I was so enamored with the shelf of figures that I had it installed, with most of the same objects, in the ceramic galleries when the new museum was initially furnished (fig. 19). The shelf is now in another area in the museum but with many of the same objects. As it turned out, the chosen few were made in the mid-eighteenth century at three different factories within about a ten-year period.

Due to its size and equal left and right direction of motion, the Chelsea figure of a finch seemed appropriate for the very top. The Derby grape gatherers with their graceful movements were logical for the other two top spaces. They were to fit into the fretwork galleries that surrounded the top sections of the shelf, but, alas, they just wouldn’t fit, so fitted discs were applied to the top of the fretwork and clamps were devised to hold the porcelain in place. The two pairs of birds sitting on the roofs came next, graduating in size—the smaller pair Chelsea, the larger ones made at Derby. On the upper center shelf are a Derby ewe, ram, and goat.

On the lower shelf sat two Chelsea examples of Chinese deities copied or adapted from blanc de chine figures: Pu-tai Ho-shang, a Zen monk, and Kuan Yin, Buddhist deity of compassion. Separating them is a Derby allegorical figure sometimes considered to be Britannia (though without all her usual symbols) but who also could represent Europa, Earth, or Plenty. The two right and left larger shelves on the sides house a large Derby group of Chinese figures and a Britannia. I have chosen to add an enlarged photo of the latter (fig. 20), since it is included in my discussion of the Vauxhall Britannia figure above.

When I was at Williamsburg we referred to this figure as being in the “girl in a swing” group, named after one figure in the group of that form. It was called that only because no one knew for sure who made it and where it was made. Thanks to recent archaeology and finer research, we now know that the group was made by Charles Gouyn, formerly at Chelsea who opened his own pottery on St. James Street, Westminster, and produced the series.

JOHN C. AUSTIN graduated from Tufts University, in connection with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, with a B.F.A. He did his graduate work at the Courtauld Institute of the University of London and at the Victoria and Albert Museum. On returning from London, he was hired by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation as a curatorial assistant and eventually became the first specialist curator at that institution—Curator of Ceramics and Glass. After an early retirement, Austin was granted the honorary title of Curator Emeritus, Ceramics and Glass. He prepared two books on the ceramics at Colonial Williamsburg, Chelsea Porcelain at Williamsburg and British Delft at Williamsburg, and curated a traveling exhibition of Williamsburg’s delft collection for two years after his retirement.

In his retirement Austin researched and collected the works of a twentieth-century ceramic designer and potter, J. Palin Thorley. He published his preliminary findings in two issues of Ceramics in America, exhibited Thorley’s wares in major museums, and lectured on the subject. Austin has continued to research Thorley’s life and work, and it is hoped that his new findings will be published. Austin donated Thorley’s personal and business papers to the Rare Manuscript department of the Swem Library at the College of William and Mary, and it is anticipated that Austin’s research material and more of his objects will also go there.

In addition to being a founding member of the American Ceramic Circle, Austin was a perpetual member of its board and served two terms as president and seven years as chairman. He is an honorary member of several regional ceramic societies across the country.

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, in association with Jonathan Horne, 1994).

John C. Austin, Chelsea Porcelain at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977), appendix. The entire 1755 catalog was reprinted from restored and enlarged photographs of the original Chelsea catalog.

Graham Hood, The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1991).

Sale, Bonhams, London, October 3, 2012, lot 62.

T. H. Clarke, “The Meissen Monkey Band,” Sotheby’s Previews, September–October 1989. Even though the watercolors had been in the archives of the Meissen factory since the 1750s, they were not discovered until about twenty-five years ago.

Austin, Chelsea Porcelain at Williamsburg, appendix.

Raphael W. Read, A Reprint of the Original Catalogue of One Year’s Curious Production of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory Sold by Auction by Mr. Ford, on the 29th March, 1756...(1756; reprint, Salisbury: Bennett Bros., 1880) (emphasis in original); and George Savage, 18th-Century English Porcelain (London: Rockliff, 1952), appendix VIII, pp. 352–415.

Graham Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia: The First American Porcelain Factory, 1770–1772 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va., 1972).

For more information about this organization, visit www.AmericanCeramicCircle.org.

American Ceramic Circle Bulletin / 1970–1971, no. 1 (1975): 3.

Ibid., p. v.

Warmstry flutes, a particular style of vertical fluting, is named after the eighteenth-century Worcester Warmstry House Factory.

Samuel M. Clarke and John C. Austin, Worcester Porcelain in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1987).

John M. Graham and Kathryn C. Buhler, The Campbell Museum Collection (Camden, N.J.: Campbell Museum, 1969), and Graham and Buhler, The Campbell Museum Collection, 2nd ed., rev. and enlarged (Camden, N.J.: Campbell Museum, 1972).

Donald L. Fennimore and Patricia A. Halfpenny, Campbell Collection of Soup Tureens at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis Du Pont Winterthur Museum, 2000).

Graham and Buhler, Campbell Museum Collection, fig. 73.

Charlotte Jacob-Hanson, “A Giles Italianate Service: Fifteen Worcester Plates Reveal a Decorative Grand Tour,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 17 (2013): 16, fig 9.

Cyril Cook, Supplement to the Life and Work of Robert Hancock: A Supplementary Account of His Engravings on 18th-Century Bow and Worcester Porcelain, Salt-glazed Plates, and Battersea and Staffordshire Enamels (London: Chapel & Hall, 1955); and Joseph M. Handley, 18th Century English Transfer-printed Porcelain and Enamels (Carmel, Calif.: Mulberry Press, 1991).

Roderick Jellicoe, “Liverpool Porcelain Figures, Fact or Fiction?” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 28 (2012): 175.

Bernard Watney, Longton Hall Porcelain (London: Faber and Faber, 1957), pl. 77.

Bernard Watney, “The Vauxhall China Works, 1751–64,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 13, pt. 3 (1989): 212–27.

Ibid., pl. 212a&b.