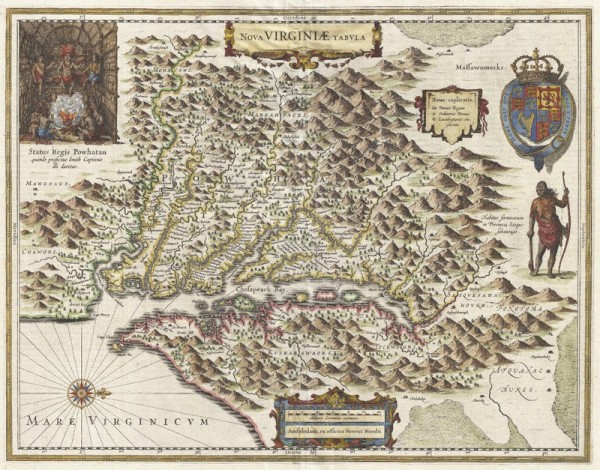

Henricus Hondius’s Nova Virginiae Tabula, map of the Virginia colony and the Chesapeake Bay, 1630. 15 1/2" x 19 1/2". (Geographicus Rare Antique Maps Cooperation Project.)

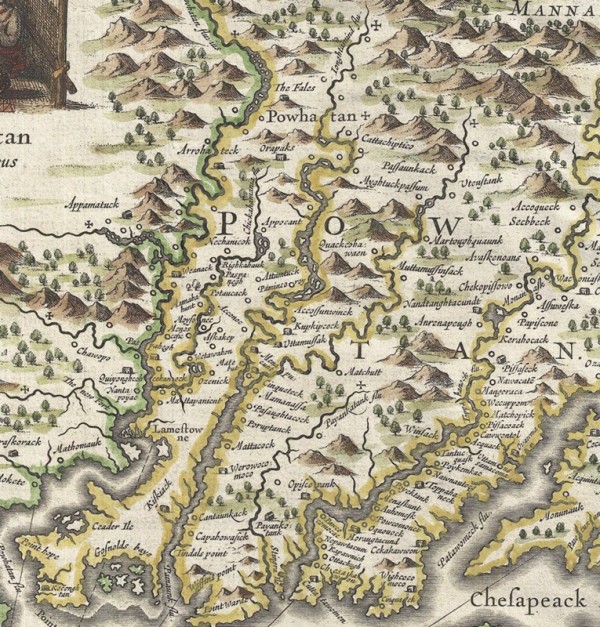

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 1 showing the location of Berkeley Hundred. On March 22, 1622, Opechancanough, the paramount chief of the Powhatan Chiefdom, commenced a series of deadly surprise attacks on English settlements and plantations along the James River. More than three hundred colonists were slain, nearly a third of the young colony’s population. George Thorpe, an investor in the Virginia Company of London and a resident at Berkeley Hundred, was among the dead.

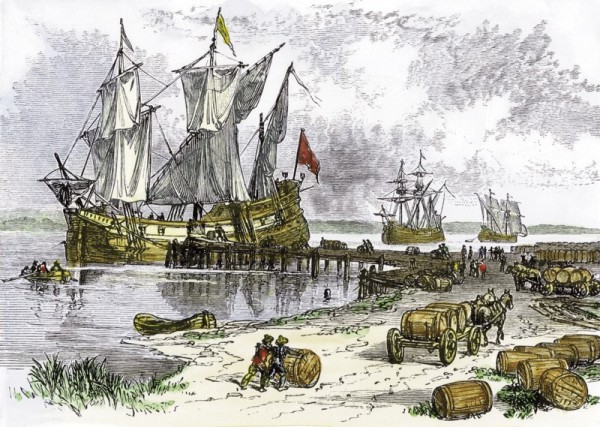

Anonymous, Sailing Ships Loading Tobacco at Jamestown in Virginia Colony, 1600s. Hand-colored woodcut of a nineteenth-century illustration, ca. 1880. (© North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy Stock Photo.) Archaeological research of the English settlements in Virginia—from the 1607 James Fort to the dispersed settlements that characterized the later seventeenth century—has revealed that individuals with the means to do so imported high-quality European and Asian ceramics to mediate the practical, social, and cultural aspects of their lives. The assemblages, largely transshipped from London and Plymouth, England, include wares that are uncommon in English households. Even the English coarse earthenwares, drawn chiefly from the potteries of London and Surrey-Hampshire, comprise many specialized shapes that are rare in contexts of the mother country.

Andries van Eertvelt, The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies on 19 July 1599, 1610–1620. Oil on panel, 22" x 36". (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.) Dutch traders made significant inroads to the Chesapeake area in the first quarter of the seventeenth century by establishing close mercantile relationships with the English settlers in Virginia and Maryland. Colonists encouraged this trade, which was opposed by London merchants and the English government, because they could exchange tobacco for household and luxury goods at a much better rate than that provided by the mother country. This was the golden age of Dutch maritime, and commercial activities and merchants (some of them English factors based in the Netherlands) were engaged in the extensive movement of goods around the world. Many of the Chinese, Dutch, German, Italian, and Portuguese wares found on early Virginia sites can probably be attributed to Dutch traders, some of whom established trading posts in the colony.

Wine cup, Jingdezhen, China, 1600–1640. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) More than a dozen of these diminutive cups with flame-frieze decoration have been reported from early-seventeenth-century Virginia archaeological sites. These fine cups were once thought to be Imperial ware, reserved for use by the Chinese elite. Now they are recognized as status vessels made for export. They have been found on a number of Dutch shipwrecks (such as the Witte Leeuw, 1613, and the Hatcher, 1643) and terrestrial sites dating to the first half of the seventeenth century. This example was recovered from the Walter Aston Site, Charles City County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Dish, China, 1613. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This Chinese porcelain dish was recovered from the site of the Witte Leeuw shipwreck of 1613. Cargoes of porcelain wares were being received in Europe on Portuguese ships from the turn of the fifteenth century, and then by the Dutch trade in the late sixteenth century. Although not common and found only in households with high social status, examples have been found archaeologically on a number of early Virginia sites and are noted in probate inventories such as the “6 litle pursline [porcelain] dishes” in Thorpe’s inventory; see Appendix.

Dish, China, 1600–1620. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 12 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Kraak porcelain was China’s first porcelain mass-produced for export to Europe. It was considered too coarse for the upper-class Chinese and too fragile for everyday use by the poor. The hand-painted designs, in underglaze blue only, are of landscapes and animals. Human figures are rarely depicted, making this porcelain suitable for Islamic markets as well. Buddhist and Daoist good-luck symbols make up the paneled border decorations.

Dish, Pickleherring potworks, Southwark, London, England, 1625–1630. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) In decorating their wares, early London and Netherlandish tin-glazed potters adopted the popular style from late Ming porcelain of China’s Wan Li period (1573–1619). One of the most popular motifs, “bird-on-rock,” is shown on the central design of this dish and appears on English tin-glazed wares. Evidence of the early London tin-glazed dishes is relatively scarce in Virginia archaeological contexts of the first half of the seventeenth century.

Mug, Lisbon, Portugal, 1635–1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. H 3 3/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Portuguese tin-glazed wares are frequently found in early Virginia archaeological contexts. A parallel vessel to the mug shown here was found in York County, Virginia, and is associated with a high-status household that had dealings with merchants in the Netherlands. The Dutch trade may account for the presence of these mugs in Virginia, although parallels have also been found in Devon, England, an area of increasing commercial activity in the colony after the Virginia Company of London lost its charters for settlement in 1624. This example was excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Floor tiles, Pickleherring potworks, Southwark, London, England, 1618–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. Both are 5 1/4" square. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo on right, Robert Hunter.)

Excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, 1620–1635 context. These medallion tiles, one depicting a camel and the other a bird, are copies of earlier tiles produced in the Netherlands and reflect the influence of Christian Wilhelm, an immigrant potter from the Low Countries who established the Pickleherring pothouse in London. Decorative floor tiles such as these indicate high-style accommodations.

Apothecary jar, Aldgate, London or Netherlands, 1590–1610. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Preservation Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jars like this were produced in the Netherlands and were among the first tin-glazed earthenwares produced in England. The form developed in the Middle East as a container for medicinal substances, which also included spices and herbs that we may consider homeopathic remedies today. Apothecary jars are among the most common ceramic forms found on early-seventeenth-century archaeological sites in Virginia. This example was excavated from the James Fort in Jamestown, Virginia, 1607–1610.

Dishes, Northern Netherlands, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware with lead glaze on back. D. (left) 7 3/4"; D. (right) 7 9/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter). In the mid-sixteenth century, Italian potters introduced tin-glazed earthenware to the Northern Netherlands and early designs were borrowed from Italian maiolica. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, a distinctive Dutch style had developed in the region that relied heavily on geometric designs. Drug jars and dishes are the most common forms found in Virginia. These dishes were found at the Chesopean Site, Virginia Beach, Virginia, in a context roughly dating to the middle decades of the seventeenth century.

Dish base (front and back), Northern Netherlands, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware with lead glaze on back. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Contacts with China that developed after 1600 led to a movement away from the polychrome decorations of the Mediterranean to the blue-and-white motifs of the Far East. The undersides of these early dishes were lead-glazed in order to save the more expensive tin enamel for application to the upper surface. Many of the dish footrings are pierced to allow hanging. This and the lack of wear on the surface of some vessels suggest that dishes were not necessarily used for the consumption of food but to display status. This piece was excavated at the Chesopean Site, Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Ward, James City County, Virginia, 1620–1635. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Thomas Ward arrived at Jamestown in 1619 as the indentured servant to a bricklayer and is the first documented potter in the English colonies. The forms and styles of his vessels reflect a combination of the London-area redwares (like this thumb-impressed jar) and the products of the potteries on the border of Surrey and Hampshire counties. This example was excavated at the Nomini Plantation Site in Westmoreland County, Virginia.

Detail of the thumb-impressed rim on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14. When the pot was thrown on the wheel, an extra coil was applied to reinforce the rim. The thumb impressions are both functional and decorative. This technique is also found on London redwares of the period.

Milk pan, Virginia, attributed to Thomas Ward, James City County, Virginia, 1620–1635. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Since the late sixteenth century, milk pans were used as settling vessels to separate cream from milk. The form was not common in Virginia before the large-scale importation of cows in the second quarter of the seventeenth century.

Dish, South Somerset, England, 1620–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This dish with wet slip-sgraffito decoration has visual attributes that are characteristic of wares produced in the village of Donyatt in South Somerset. It is therefore considered a Donyatt-type, until chemical analysis of the clays can link it to a specific kiln in the well-known potting area of southwest England. Pottery from this region was arriving in Virginia before 1610, as ships embarking for the New World stopped in at Plymouth to avail themselves of goods they could acquire more cheaply than in London. This example was excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Jug, South Somerset, England, 1600–1650. Sgraffito slipware. H. 8 3/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Meg Eastman, Virginia Historical Society.) English potters began producing sgraffito slipwares by 1600. The earliest examples are decorated with simple patterns of incised lines. The decoration became more elaborate over time, as demonstrated on a 1666–1690 bottle from St. Mary’s City, Maryland, decorated with birds and letters. This example was found at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, in a 1620–1635 context.

Cup and mug, Surrey-Hampshire border ware, 1600–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of cup 3"; H. of mug 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These two drinking vessels were made in the potteries located on the Surrey-Hampshire border in England. For three hundred years beginning in the fourteenth century this area was a major source of quality utilitarian wares for the London market. Border wares in both everyday household forms and those with a specialized function—such as alembics, schweinetopfs, and double dishes—were part of the ceramic assemblage of the first Jamestown colonists in 1607. The earthenware has been found on seventeenth-century sites on the eastern North American continent from North Carolina to Newfoundland. These examples were found at Wills Cove, Suffolk, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Jug, Frechen, Germany, 1600–1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Vessels from Frechen, a small village near Cologne, were the most widely traded German stonewares of the seventeenth century. While this wide-mouthed jug is undecorated, it is a form that was highly prized by English consumers, who mounted the necks and bases with silver. Fragments of these German vessels have been found on many early archaeological sites in the Tidewater region of Virginia.

Jug neck and body, Frechen, Germany, 1620–1630. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments are from a large Bartmann (“bearded man” in German) jug, also known since the seventeenth century as a “Bellarmine.” Shipped to Jamestown as containers for alcoholic beverages, these jugs are among the most common ware types found in early colonial contexts. The random accents of cobalt coloring on this vessel made it more costly than undecorated examples. These fragments were found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Schnelle fragments, Westerwald, Germany, 1600–1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Westerwald stoneware is commonly found in North American contexts dating 1620–1775, but it is rarely found in England prior to the second half of the seventeenth century. This suggests that the source of earlier Westerwald vessels in England’s colonies was a result of the extensive Dutch trade. The schnelle, or elongated tankard, form was first used in the sixteenth-century German potting industries in Siegburg and Raeren. It is seldom documented in colonial Virginia contexts. These fragments were excavated at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Jug fragment, Westerwald, Germany, 1630–1650. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Stoneware products of the Westerwald continued to find their way into the Virginia colony throughout the seventeenth century. Mugs, chamberpots, and examples of these globular, big-bellied jugs are frequently seen in archaeological contexts. Relief decoration in the form of sprigged applied rampant lions and medallions is typical on these decorative but utilitarian wares. This example was found in Gloucester Point, Virginia.

Dish rim fragments, Germany, 1570–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. Top: Weser slipware; bottom: Werra ware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Both of these highly decorative German slipware types were exported in great numbers from Bremen to the Low Countries and from there to England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The wares are found in small numbers on Virginia’s early-seventeenth-century archaeological sites, with Werra ware being much more common than Weser. These fragments were found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Weser slipware dish, Germany, 1570–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) Weser ware was made in a number of production sites between the Weser and Leine rivers. Unlike Werra ware, Weser is a hard white fabric that was fired once. Designs are simple, consisting of geometric dots, lines, and squiggles in red-brown and green on a yellow ground. Weser ware is present but uncommon on early-seventeenth-century Virginia sites. Dishes comprised a major part of the industry’s output but hollow-ware forms have also been excavated: a small jug was found at Jamestown, Virginia, and a double-handled pot with rouletted decoration was located in Hampton, Virginia.

Werra slipware dish, Germany, dated 1620. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 13 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) This ware used to be known as Wanfried, for the village on the Werra River where large numbers of wasters were found in the late nineteenth century. Now kiln sites for the ware have been located more broadly along the river, with many biscuit wasters indicating that the vessels were fired twice. Dishes and bowls are most commonly found in Virginia on sites dating to the first quarter of the seventeenth century. The low-fired red fabric is decorated with white, green, dark brown, and yellow colors, with the central motif typically outlined in sgraffito. Common designs include flora, fauna, soldiers, and individuals holding wineglasses. Often the dishes are dated.

Dish fragments, North Holland, 1620–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) German and Dutch potters were using a variety of slip decorating techniques in the early 1600s. The distinctive Dutch slip-trailed wares are sometimes found in American contexts of the 1630s–1660s. Two-handled drinking-bowl forms are known, in addition to broad dishes represented by these fragments found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Dish, North Holland, 1620–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 10 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) The highly decorated Dutch slipwares usually have exuberant animal, bird, floral, pomegranate, and geometric designs. White slip, trailed directly onto the earthenware bodies, was often highlighted with splashes of green oxide beneath a clear lead glaze.

Bowl, northern Italy, 1575–1625. Sgraffito slipware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Sgraffito slipware bowls and flanged dishes produced in Pisa, Italy, are found in Virginia contexts dating to the second and third quarters of the seventeenth century. The red alluvial clay is covered on the interiors of all forms with a thick white slip through which motifs are incised. Ocher and green copper oxide are used to highlight the design, which in Virginia is usually a flower or a bird, as shown here. This bowl was recovered from Jamestown Island, Virginia, in a second-quarter-of-the-seventeenth-century context.

Dish, Pisa, Italy, 1600–1650. Marbled slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This ware, made in Pisa, is uncommon in England until close to the mid-seventeenth century. It frequently appears on Virginia sites earlier, which—like the other Italian, Netherlandish, and Portuguese wares—may be a result of the robust Dutch trade with the English colonies. Dishes and bowls are the most common forms. This dish, the center portion of which has been reconstructed, was excavated at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Costrels, northern Italy, 1580–1650. Marbled slip-decorated earthenware. H. (left) 10 1/4", H. (right) 10 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) Fragments of these distinctive-looking wine flasks have been found in early Virginia contexts. The four molded lion’s-head lugs were meant to accommodate a strap or cord for suspension. The bichrome decoration of yellow and dark brown without the addition of green is considered to date to the later years of production. The narrow form of the example on the right is also a later shape.

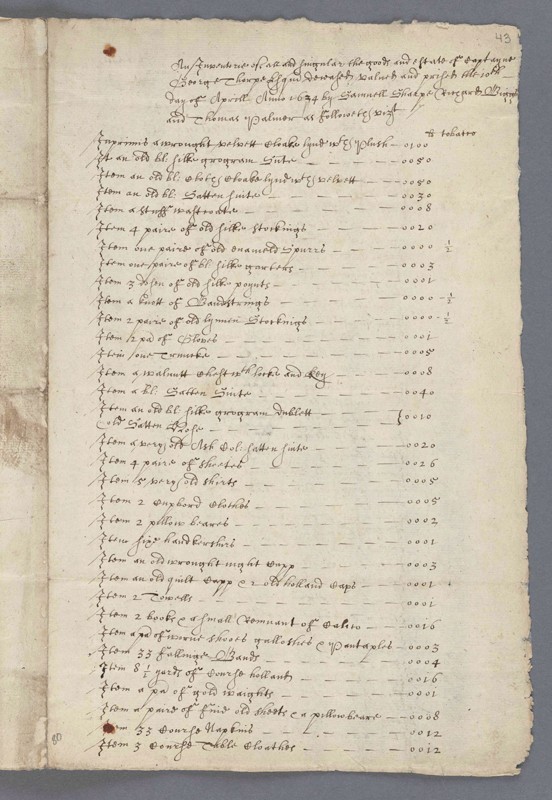

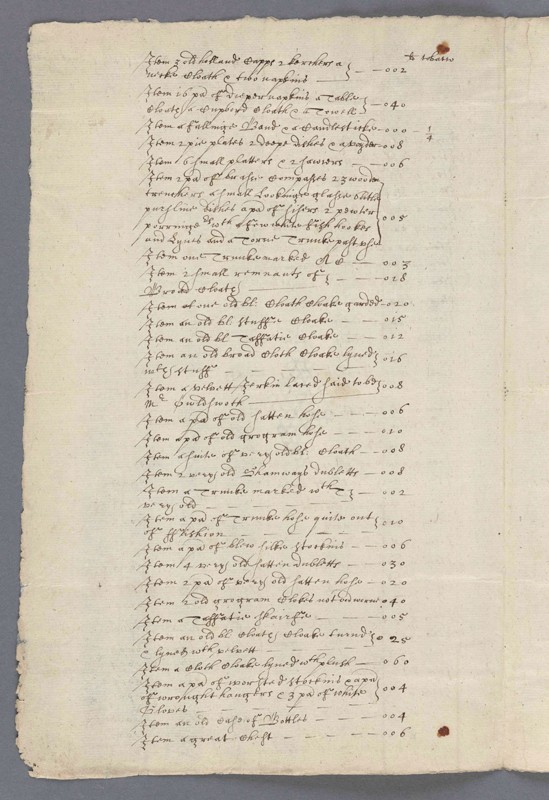

Page 1 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

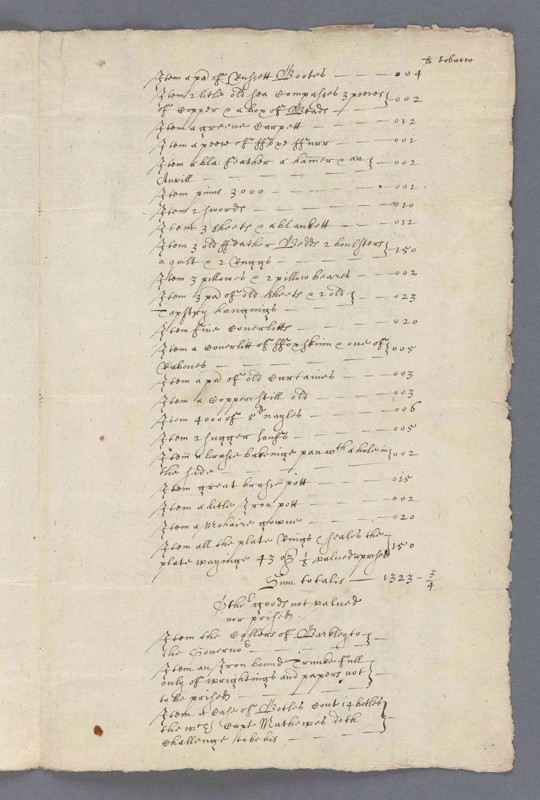

Page 2 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

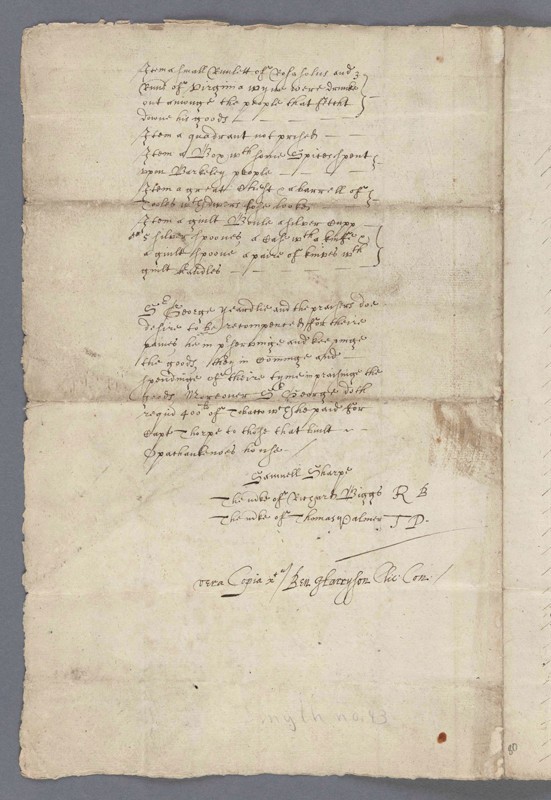

Page 3 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

Page 4 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

EDITOR'S NOTE: In this article, Martha McCartney presents the historical context for the earliest household inventory yet discovered for Virginia. Peter Wilson Coldham, a British scholar whose knowledge of Virginia records in overseas archives was unparalleled, surmised that inventories of early colonists’ estates were discarded after the probate process had been completed. This surviving document is thus rare indeed, and promises to provide many exciting insights into the material world of Virginia’s early colonists. Historians, curators, and archaeologists have long used inventories to better understand a given household in terms of economic and social status. However, those in these same disciplines are also aware of the limitations and biases inherent in inventory data. In particular, archaeologists have learned that ceramic listings, if present at all, are often ambiguous and usually incomplete. In an attempt to offer a corrective, Beverly “Bly” Straube has contributed the illustrations for this article, with captions that explain some types of early-seventeenth-century ceramics that have been archaeologically recovered from other Virginia household sites similar in composition and economic standing. It is hoped that this combined presentation will underscore the rich material culture of what is often considered a frontier outpost in the New World.

George Thorpe, an investor in the Virginia Company of London and a member of the Society of Berkeley Hundred, died at Berkeley Hundred on March 22, 1622, at the hands of attacking Indians. An inventory of his possessions, compiled two years after his death, is the earliest known account of a Virginia colonist’s estate. While few ceramics are listed, the inventory reflects the material world of an English gentleman in Virginia.

George Thorpe was the son of Nicholas Thorpe, Esquire, of Wanswell Court in Gloucestershire, and Mary Wilkes, his wife. Both families were prominent in England’s West Country. On February 20, 1598, when George was admitted to the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court, he was described as a gentleman “Late of Staple Inn.” When Nicholas Thorpe made his will in early 1600, he named twenty-four-year-old George as executor and residual heir but made generous bequests to numerous members of his extended family. These legacies depleted his assets but George was able to retain Wanswell Court and a portion of his patrimony.[1]

On July 11, 1600, George Thorpe married Sir Thomas Porter’s daughter, Margaret, in the Church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, London. His in-laws included at least four titled noblemen who went on to become major investors in the Virginia Company, chartered by James I in 1606. These influential connections paid off in time, and George received his first court appointment, that of Gentleman Pensioner, a post he held from 1606 through 1614. As a Gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, his official duties placed him in London, where he had access to the monarch and other members of the royal household. He also had to be available for military duty, and in 1608 he and seven of his servants were among the “able and sufficient” Gloucestershire men considered “fit for His Majesty’s Service in the Wars.” In 1609 George Thorpe obtained a fifty-one-year lease for some fishing grounds along the Severn River, where his forebears had held fishing rights for generations. Arnold Oldisworth, a fellow leaseholder and one of George’s kinsmen, joined him in a costly and futile lawsuit stemming from the meandering river’s impact on riparian rights.[2]

Margaret Thorpe died in March 1610.[3] When George remarried, in February 1611, he wed another Margaret, a well-connected Londoner who was the daughter of David Harris of Bristol and the niece of Sir John Bennett. Together, the Thorpes produced five children, at least three of whom survived infancy. George was elected to the House of Commons in 1614, representing Portsmouth, and took part in the so-called Addled Parliament, whose members debated the king’s right to levy taxes on commodities without their consent. On June 29, 1615, George was among the adventurers King James I authorized to establish a plantation in the Somers Isles, also known as the Bermudas. Five years later George invested in the Virginia Company of London and was named to the company’s council.[4]

The Society of Berkeley Hundred

In 1618 George Thorpe and his cousin Sir William Throgmorton joined Richard Berkeley and John Smyth of North Nibley, two longtime investors in the Virginia Company, in forming a partnership they called the Society of Berkeley Hundred.[5] Later, Sir George Yeardley joined in. The Society’s purpose was to establish a private plantation in Virginia, a settlement they planned to call Berkeley Hundred. They received a charter from the Virginia Company on February 3, 1619, and two weeks later, when Thorpe sent a letter to Yeardley who was en route to Virginia, he enclosed a copy of that document, noting that it had been written by his own “Virginian boy,” that is, an Indian youth.[6] In April 1619 Virginia Company officials informed newly arrived Governor George Yeardley that they were planning to send George Thorpe to the colony to serve as deputy for the so-called College land, a settlement that encompassed ten thousand acres near the head of the James River. Thorpe’s contract outlined his administrative duties and stated that he was to be compensated in land and supplied with servants or tenants.[7]

Planting a Settlement

During the spring and summer of 1619, the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s investors discussed plans to procure the fifty or so servants and tenants they needed to establish their plantation. They also began accumulating the provisions and other supplies their settlers would require once they reached Virginia. In July 1619 George Thorpe informed his fellow investors that he had received the weaponry that would be sent to Berkeley Hundred. As the summer drew to a close, so did preparations for the Society’s Virginia adventure. Edward Williams, a Bristol merchant, signed a contract on August 18, 1619, agreeing to allow the Society of Berkeley Hundred to use the Margaret, a ship of 45-tons burthen. He promised to see that his vessel was in good repair and sufficiently victualed and he agreed to provide a crew of nine: a master plus seven other men and a boy. The Society’s investors, on the other hand, stipulated that Henry Penry was to be the ship’s master and that Toby Felgate was to serve as pilot. The Margaret was scheduled to set sail on September 15, 1619, weather permitting. Captain John Woodlief, the Buckingham merchant commissioned to serve as governor of the Berkeley Hundred settlement, agreed that the ship would stay in Virginia no more than fifty days. At the end of August, the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s investors provided Captain Woodlief with some very specific instructions on how the settlement was to be organized.[8]

A list of the cargo the Society’s investors put aboard the Margaret reveals that their venture was carefully planned and costly. George Thorpe supplied some items that would be critical to the settlers’ defense: twenty-four muskets and two lighter firearms known as calivers; three barrels of gunpowder and matches; lead for forming into bullets; pike heads; three corselets or torso-covering body armor; and sixteen swords, sword belts, and bandoleers (belts strung with containers for gunpowder). He sent along literally thousands of large and small glass beads and some copper, in anticipation of trading with the Indians, and he furnished substantial quantities of seeds that could be used to plant gardens for sustenance and medicinal purposes. He also had a large quantity of buttons packed into a barrel and readied for shipment. Thorpe, reputedly a religious man, made provisions for the colonists’ spiritual well-being by supplying two church Bibles, two copies of the Book of Common Prayer, and volumes called The Practice of Piety and The Playne Man’s Path Way.

Staple foods, such as cheese, oatmeal, peas, meal, spices, and butter, were carted to the Margaret. Also loaded aboard was an abundance of treenware—wooden platters, dishes, trenchers, bowls, and spoons for dining. Culinary equipment included a dozen skimming dishes and saucers, a ladle, spits for roasting meat, kettles, pots and pothooks, skimmers, and a deep wooden bowl in which mustard could be prepared. Horn cups and metal cans (cylindrical drinking vessels that came in various sizes) were provided for the consumption of beverages. Common household items such as lanterns, candlesticks, andirons, pot-hangers, shovels and tongs, soap, dowlas sheets and bolsters, locks, and padlocks were put aboard. Most of the items loaded onto the Margaret were packed in chests and barrels. Proper decorum was to be maintained in the settlement whose flag was to be mounted on a tasseled pike. A drum was sent along for drummer George Hale, who would use it to summon the settlers to meals and worship or to sound an alarm.

The Berkeley Hundred colonists were furnished with substantial quantities of readymade clothing, articles such as suits of apparel, shirts, falling bands (large, flat, loosely fitting collars), yarn stockings, caps, handkerchiefs, garters, and two hundred pairs of shoes. They also were supplied with points (the metal-tipped laces they used to fasten their clothing) and with thread, needles, buttons, and shoe thread, presumably so that they could keep their clothing and footwear in usable condition. Also present were substantial quantities of dowlas for making sheets and bolsters, plus frieze (a coarse woolen), silk taffeta, probably for use in making clothing for the settlement’s leaders. Buckram, a coarse fabric used as a stiffener in clothing and for wrapping merchandise prior to storage or travel, was also included. Tools for clearing land, planting crops, building houses, and making furniture were provided to the settlers, along with literally thousands of nails and nets and hooks for catching fish. Specialized implements used in surveying, blacksmithing, coopering, carpentry, tailoring, and joinery were furnished to the skilled workers the Society was sending to the colony. Quires of writing paper were dispatched to Berkeley Hundred’s sergeant, to kitchen clerk Roland Painter and his sons, and presumably to the settlement’s leaders. Also present were bread and wine, elements intended for use in Holy Communion. Some fifteen gallons of aqua vitae, five-and-a-half tuns of beer, and cider were loaded aboard the ship, along with water, fish, bacon, suet, bread, and biscuits. Naval supplies that might be needed at sea, such as canvas for repairing sails, caulking material, and a supply of rope, were loaded aboard. All of these items were enumerated in the Margaret’s manifest.[9]

The Margaret left Kingsrode in Bristol on September 16, 1619, with the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s first group of settlers and in accord with George Thorpe’s instructions. Ferdinando Yates documented the voyage. After a very difficult crossing, the ship arrived at the mouth of the James River on the evening of November 30 and landed at Old Point Comfort. Among the thirty-six Berkeley Hundred colonists under Captain John Woodlief’s command were a number of artisans and skilled workers, some of whom were multitalented. Thomas Coopy, for example, was a carpenter, smith, turner, and fowler, whereas Humphrey Plant was a sawyer and carpenter. Thomas Davis was a cooper and shingle-maker; gun-maker and smith Charles Coyse was a fisherman but also knew how to make pitch and tar. Also included were shoemaker Christopher Nelmes, joiner Richard Godfrey, and others capable of serving as cooks, gardeners, coopers, and smiths. The expertise of surgeon John Singer would have been invaluable while the Margaret was at sea and also after the settlers touched land.

The Society of Berkeley Hundred made contractual agreements with their tenants, all of whom were considered free men, and promised an allotment of land in exchange for a certain number of years’ work. For instance, husbandman Robert Coopy was to receive thirty acres of land in exchange for three years of work and a modest annual rent. On December 4, Governor George Yeardley had Secretary of the Colony John Pory record the names of the men aboard the Margaret when it reached Jamestown. Shortly thereafter, he sent them to the land he had chosen for them, a location on the upper side of the James River, in the immediate vicinity of the plantation still known as Berkeley. According to the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s instructions, when Captain John Woodlief and the first contingent of settlers reached their assigned acreage, they were to kneel and give thanks for their safe arrival. That day of thanksgiving, to be observed annually, was America’s first.[10]

The Society’s investors ordered Captain Woodlief to see that substantial, “homelike” houses were built, dwellings that were roofed over with boards. Two of the settlement’s buildings were to be very sturdily constructed. One was to serve as a storehouse in which arms, ammunition, armor, victuals, and tools were to be kept. The other was a substantial hall where the colonists, who were expected to lead a communal lifestyle, could assemble for meals and gather for meetings and daily worship. Until Berkeley Hundred’s storehouse was built, the community’s weapons, staple foods, and tools were to be kept in the common warehouse at Jamestown or in the granary at nearby Bermuda Hundred. The settlers were to erect a palisade that was seven-and-a-half feet high, enclosing four hundred acres of land in which crops could be grown and livestock could graze. Captain Woodlief, as community commander, was to be assisted by ensign Ferdinando Yates, who was placed in charge of the settlement’s armor and agricultural tools. John Blanchard was to be steward of the household and clerk of the store, and Roland Painter was designated clerk of the kitchen. Henry Perce, a gentleman, was to be usher of the hall and Thomas Partridge, if willing, was to serve as bailiff of husbandry. Yates, Blanchard, Painter, Richard Godfrey, and Thomas Coopy, considered men of discretion, were to take their meals at the captain’s table. Each night, several male settlers were to take turns standing watch, forming a corps de garde. Captain Woodlief, as Berkeley Hundred’s chief merchant, was authorized to trade with the Indians and to represent his settlement’s best interests when trading with other colonists and merchants.[11]

George Thorpe of Berkeley Hundred

George Thorpe sailed from England on the London Merchant on March 27, 1620, less than four months after the Margaret landed at Berkeley Hundred. He quickly demonstrated that he was a capable leader and on June 28, 1620, the Virginia Company’s council named him to the colony’s Council of State, whose members served as advisers to the governor and functioned as a judiciary body. Thorpe’s activities in Virginia, recorded in his correspondence and in records generated by the Virginia Company, reveal that he was knowledgeable about the legal system and the laws by which the Virginia colony was governed. In fact, Secretary John Pory, who became acquainted with Thorpe after he reached Virginia, described him as “an Angell from Heaven” and said that he was of inestimable benefit to the colony. Thorpe was held in such high esteem that the Virginia Company’s court ordered him to assist Governor George Yeardley in investigating Lady Cisley Delaware’s allegations against Sir Samuel Argall’s mishandling of her late husband’s estate. During the latter part of 1620, Yeardley heaped praise upon Captain George Thorpe and told company officials that he would “be the most ffitt man” to take over his governorship and would have no problem following their orders.[12]

In a letter to Berkeley Hundred investor John Smyth dated December 19, 1620, George Thorpe acknowledged that some of the people the Society had sent to the colony were dead. He attributed some deaths to “disease of theire minde”[13] but he declared that his own health had never been better. He said that the victuals sent from England were overpriced and pointed out that the newly arrived colonists had not expected to drink water instead of beer. He added that the settlers had found a way to make a good beverage from Indian corn and that sometimes he preferred it to good, strong English beer. In closing, Thorpe said that he wanted his wife and children to join him in Virginia and asked Smyth to make sure that they were all right. Virginia Company officials seem to have been optimistic about Berkeley Hundred’s future and in 1621 they sent George Thorpe a barrel of seeds.[14]

During late spring 1620 there was a change in the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s leadership, for Sir William Throgmorton transferred his interest in the Society to William Tracy, a Virginia Company investor and resident of Hayles in Gloucestershire. An undated amendment to the Society’s charter stipulated that the Berkeley Hundred colonists were to produce salable staple commodities, such as corn, wine, oil, flax, pitch and tar, soap ashes, iron, and clapboard, and were not to rely “wholly or chiefly upon Tobacco.” Tracy told John Smyth that he needed to supply the plantation with cattle and horses if the colonists were to have a bloomery. He said that he should be able to borrow some goats and silkworms from Lady Elizabeth Dale, whose land in Shirley Hundred was nearby. By July 1620 William Tracy had been named to Virginia’s Council of State. He began making plans to go to Virginia aboard the ship Supply, taking along his wife, Mary, son Thomas, daughter Joyce, and some servants. Near the end of August, the Society of Berkeley Hundred gave Tracy and George Thorpe a commission to govern Berkeley Hundred and Captain John Woodlief’s authority was set aside.[15]

The Second Group of Settlers

When the Supply was readied for departure in September 1620, the same types of foodstuffs, clothing, tools, and household goods were loaded aboard as had been sent on the Margaret the previous year. This time some medicinal drugs were included, probably for the healing work of Robert Pawlett, a surgeon and ordained clergyman, who was among the fifty passengers accompanying William Tracy to Berkeley Hundred. Numerous pairs of “women’s scissors,” shears, and tailors’ shears were sent along, as well as sleeping mats, rugs, two grindstones, hundreds of yards of fabric of various types, shoes, and readymade clothing. The second group of Berkeley Hundred colonists took along a much larger supply of defensive weaponry than had been loaded aboard the Margaret in 1619, probably at the recommendation of the settlers already living in Virginia. Also aboard the Supply were seeds for the colonists’ gardens and fruit trees, scion wood for grafting, spices, and large quantities of blue and white trade beads. Barrels of beef and pork were brought on board, along with cod and other fish procured from Newfoundland. Also on hand were more than sixty gallons of aqua vitae, eighteen tuns of beer, and sixty gallons of sack. A hogshead of new cider was sent to George Thorpe along with a copy of the commission he received from the Society of Berkeley Hundred and the Virginia Company’s instructions, encouraging the production of artificial wine and discouraging tobacco production.

The Supply, with fifty men, women, and children, arrived at Berkeley Hundred on January 29, 1621. Among the passengers were eight gentlemen, two of whom decided to return to England at once.[16] The second group of Berkeley Hundred colonists, like the first, was composed of servants and tenants, most of whom were skilled workers and experienced husbandmen. The Society’s tenants were promised food and shelter until they could be given a furnished house. As sharecroppers, they were to be allocated acreage on which they could grow food crops and keep livestock. Society servants who completed their three- or four-year terms of indenture also stood to receive land.[17]

The Rev. Robert Pawlett’s contract with the Society of Berkeley Hundred stipulated that he was to commence serving as the community’s minister, surgeon, and physician as soon as he reached Berkeley Hundred. He was supposed to share a dwelling with George Thorpe and William Tracy, who were obliged to pay him twenty pounds apiece. Pawlett’s stipend was to be supplemented by Society investors Richard Berkeley and John Smyth. At the end of a year, Pawlett had the option of returning to England or staying on in the colony in a salaried position. On July 16, 1621, the Virginia Company designated Pawlett a provisional councilor and eight days later he was named to the Council of State.[18]

Christianizing the Indians

William Tracy died within two months of his arrival at Berkeley Hundred, leaving George Thorpe in sole command. Thorpe continued to be responsible for the servants at the College and he tried to advance the Falling Creek ironworks and other Virginia Company projects. His correspondence reveals that he was optimistic about the colony’s economic future, but as a deeply religious man he believed that it was important to convert the Indians to Christianity. In mid-May 1621 he informed Virginia Company officials that most colonists treated the natives disdainfully rather than charitably. He recommended that the company send over some apparel and household goods that could be given to Indian leaders to curry their affection. In the wake of Thorpe’s letter, the Virginia Company urged the colony’s governing officials to promote religious conversion and to treat the Indians justly so that the peace would be maintained and old quarrels would not be resurrected.[19]

On June 22, 1621, George Thorpe informed company officials that he was going to visit the Indians’ principal leader, Opechancanough, whom he hoped to convert to Christianity. He said that the Indians had expressed their concern that the colony’s incoming governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, would not uphold the peace agreements that had been forged during Governor George Yeardley’s administration. Even before Thorpe’s letter reached England, Virginia Company officials ordered Wyatt to see that “the best meanes bee used to draw the better disposed of the natives to converse with or people” and expressed their hope that the Indians “may growe to a likeing and love of Civility, and finallie bee brought to the knowledge and love of god and true religion.”[20]

When Governor Wyatt arrived in October 1621, he sent Thorpe to see Opechancanough, with assurances that he would continue his predecessor’s policies. Virginia Company officials also offered encouragement to the natives and in January 1622 sent gifts to Opechancanough and his brother, along with a message of friendship. Contemporary accounts reveal that Thorpe went to great lengths to win the Indians’ trust and affection and that he focused his attention on Opechancanough. However, between January and March 1622 relations between the Indians and colonists rapidly deteriorated after one of the paramount chief’s favorites, a war captain named Nemattanow, also known as Jack of the Feather, killed a settler named Morgan. Two or three days later, when two of Morgan’s male servants encountered Jack, who was wearing their master’s cap, they assumed the worst and killed him. This enraged Opechancanough, who, according to Captain John Smith, orchestrated a devastating attack, which occurred only two weeks later.[21]

George Thorpe’s Martyrdom

On Friday, March 22, 1622, the Powhatan Indians attacked the numerous plantations that were sparsely scattered along both sides of the James River. Especially hard hit were the settlements in the river’s upper reaches. When the Indians descended on Berkeley Hundred, George Thorpe and ten others were killed. Edward Waterhouse, who was in England, recounted the Indian assault in highly inflammatory terms, basing it on what he learned from returning colonists and letters he had received. He described Thorpe as a religious martyr who was so intent on converting the Indians to Christianity that he punished anyone who antagonized them. He said that Thorpe frequently conferred with Opechancanough, gave him numerous presents, and had an English-style house built for him, a structure whose functional door lock and key fascinated the Indian chief. In fact, Captain John Smith said that the native emperor assured the settlers that “he held the peace so firme, the sky should fall or he dissolved it.” According to Waterhouse, Opechancanough professed interest in the god the English worshiped, which he said was “much better than theirs,” and led Thorpe to believe that he was in the process of religious conversion. Too late, Thorpe and the other colonists learned that it was a hoax. Waterhouse said that Thorpe’s manservant, who sensed that some treachery was afoot, tried to warn Thorpe, but Thorpe “was so void of all suspition, and so full of confidence, that they had sooner killed him, than hee could or would believe they meant any ill against him.”[22] His naïveté proved fatal.[23] Waterhouse went on to describe the Indians as a “Viperous brood” who not only killed George Thorpe, but also mutilated his corpse.[24]

Aftermath

The colonists living in the upper part of the James River who managed to survive the native assault were evacuated to positions of greater safety. Although a substantial number were taken to Jamestown Island, most were transported to Flowerdew Hundred, Shirley Hundred, and Samuel Jordan’s plantation, Jordan’s Journey, all of which were strengthened and held. At Berkeley Hundred, the Indian attack undoubtedly caused momentary chaos, since the settlement’s leader, George Thorpe, had been killed. Nonetheless, the survivors seem to have acted quickly in an attempt to reestablish order. Sixteen men from Berkeley Hundred were sent to West and Shirley Hundred Island, where some of the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s cattle were taken, but most of the Berkeley survivors went to Jordan’s Journey.[25] Archaeological research suggests that after moving to Jordan’s Journey they resumed the communal lifestyle to which they had grown accustomed at Berkeley Hundred. This mode of living contrasted sharply with the other planter households at Jordan’s Journey, which enjoyed a more independent existence.

In August 1622 John Smyth, one of the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s main investors, compiled a list of the Berkeley Hundred settlers he believed had survived the Indian attack. As it turns out, his list was highly inaccurate, for he omitted at least sixteen people’s names. Demographic records reveal that at least three prominent gentlemen—Richard Milton, Thomas Palmer, and John Gibbs—went to Jordan’s Journey and stayed on, as did Margaret Finch, Edith Halliers, William Popleton, and Richard Sheriffe Jr., a cooper. Sheriffe’s father, a carpenter in the employ of the Society of Berkeley Hundred, died at Jordan’s Journey between April 1623 and February 1624. At least four other Berkeley Hundred refugees were still residing at Jordan’s Journey in 1625. Ten people, including two nuclear families, who were living at Jordan’s Journey in 1624 were gone by early 1625 and may have died there.[26]

In July 1623, when Virginia Company investors resolved to send supplies to the colony for the relief of surviving settlers, John Smyth indicated that he was dispatching aid to his “servants now living in Virginia in Berckeley [sic] Hundred and such others as this next August I sende over to encrease them.”[27] However, after he learned that the surviving settlers had abandoned their plantation, he changed his mind. On May 24, 1624, when the Virginia Company’s charter was revoked and Virginia became a Crown colony, many of those who had invested in the colonization effort were left to ponder what the future might hold. In 1627 William Farrar, the community commander at Jordan’s Journey, was ordered to make an accounting of the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s cattle, and several years later, when he was in England, he conferred with Society investors about their plantation’s future. He would have had firsthand knowledge, obtained from the Berkeley Hundred settlers living at Jordan’s Journey. In 1632 the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s remaining investors discussed reviving their settlement, but financial support was so limited that the project never got underway. Finally, in 1637 Governor John Harvey issued to a syndicate of London merchants and mariners a patent for eight thousand acres called Berkeley Hundred, noting that they had purchased the property.[28]

The Settlement of Thorpe’s Estate

On June 20, 1622, George Thorpe’s wife, Margaret, who was still unaware of her 46-year-old husband’s death, asked John Smyth of Nibley for financial assistance, in accord with an agreement the two men had made. Several months later, after word of George’s death spread through Gloucestershire, an inquisition was held at Gloucester Castle. A jury then noted that the widowed Margaret Thorpe had life rights in the Manor of Wanswell, in accord with a prenuptial agreement she and George made on February 20, 1611, the day before they wed, and that the couple’s eldest son and primary heir, William, was only ten years old. The Court of Exchequer acknowledged that a month before George Thorpe left for Virginia he had succeeded in having the entail removed from some of his inherited property, a strategy that would free his executors to sell his acreage in order to pay his debts.[29]

As it turned out, nearly two more years would pass before Captain George Thorpe’s estate was presented for probate.[30] On March 7, 1624, when Virginia’s General Court convened as a judicial body, Sir George Yeardley was ordered to appoint men to appraise Thorpe’s personal estate. The justices expressed their uncertainty about which debts were attributable to the decedent personally and which to the Society of Berkeley Hundred. Thorpe’s inventory, presented at court on April 10, 1624, is the earliest known tabulation of a Virginia colonist’s personal effects and includes items attributed to him at the time of his death on March 22, 1622.[31]

Thorpe’s inventory was compiled by three respected men and near-neighbors: Richard Biggs of West and Shirley Hundred, Samuell Sharpe of Flowerdew Hundred, and Thomas Palmer, who had lived at Berkeley Hundred but settled at Jordan’s Journey after the Indian attack.[32] A sentence at the conclusion of the inventory stated that Yeardley and Thorpe’s appraisers expected compensation for their work. Yeardley also wanted to be paid for “preservinge and keeping the goods.” It is unclear whether he had Thorpe’s goods taken to his Flowerdew or Weyanoke plantations, which were nearby, or had them brought to Jamestown. In any case, Thorpe’s wine was “drunke out amonge the people that fetcht downe his goods.”[33] While in court on March 7, 1624, Yeardley reported that either Thorpe or the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s investors owed eight barrels of corn to the estate of Captain Nathaniel West, whose family owned Westover. In July 1624 the General Court ordered Thorpe’s administrators to repay West’s widow, Frances, and Sir George Yeardley was told to settle Thorpe’s debt with Alice Davison, the widow of Secretary of State Christopher Davison. In the same session of court, John Gibbs and Richard Milton testified that Thorpe had borrowed some corn from a Mr. Dade, probably John Dade who came to Virginia on behalf of Cecily West, Lady Delaware.[34]

In February 1625 several other people or their legal representatives made claims against the late George Thorpe’s estate. A partial summary of those debts reveals that when Thorpe provided for the people under his command, he sometimes procured staple foods and livestock from other colonists at his own expense. Thorpe’s creditors included his cousin, Lady Elizabeth Dale, from whom he had borrowed cattle and goats, and the Rev. David Sandys and the Rev. Richard Buck, two clergymen who probably performed religious services at Berkeley Hundred or the College. Thorpe also owed Sir George Yeardley for hiring the men who built an English-style house for Opechancanough. Court records reveal that Yeardley had employed Robert Fisher, a carpenter and Jordan’s Journey resident, who charged for five weeks’ work. The decedent’s greatest debts, calculated in tobacco, were owed to Yeardley, which probably explains why he was ordered to see that Thorpe’s estate was appraised.[35]

George Thorpe’s Personal Effects

On August 14, 1634, a purportedly accurate copy of George Thorpe’s inventory was presented to officials in England, in response to legal action undertaken by his eldest son, William, a resident of Bristol.[36] George Thorpe’s inventory not only reflects his status as a gentleman and community leader, it provides insight into the manner in which he was living at Berkeley Hundred. His possession of three featherbeds, three pairs of old sheets, and three pillows raises the possibility that he and his housemates, the Rev. Robert Pawlett and William Tracy, lived in the large and sturdily built structure in which the Berkeley Hundred colonists were supposed to take their meals and hold worship services, as they had been instructed to share accommodations. Thorpe was credited with two pewter porringers, six small porcelain dishes, a gilded bowl, a silver cup, five silver spoons, a knife in a case, a pair of knives with gilded handles, and a gilded spoon. Some or all of these items most likely were his personal possessions, although some objects may have belonged to his housemates. However, Thorpe also was credited with a brass baking pan, a large brass pot, several pie plates, platters and saucers, and twenty-three wooden trenchers, utilitarian objects that probably belonged to the Society of Berkeley Hundred. As the settlement’s leader, they may have been in his possession at the time of his death. The trenchers’ presence, along with four tablecloths and more than five-and-a-half dozen napkins (roughly half of which were made of diaper, a cotton or linen fabric that was woven in a simple geometric pattern), suggests that many of the residents dined communally, in accord with the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s instructions.

The late George Thorpe was credited with a substantial quantity of men’s clothing, some of which may have belonged to some of the settlement’s other gentlemen, perhaps his housemates. On hand were five black suits, two of which were made of satin, and one “very old” suit that was ash-colored or gray. Thorpe also had an assortment of black cloaks, most of which were old. One was made of shallot (a soft silk) and lined with plush. Two others were velvet-lined and a third one was interfaced with “stuffe,” a coarse woolen. One of Thorpe’s cloaks was made of taffeta, a luxury fabric.[37] He also had a mohair gown (a silky-soft garment made from the hair of Angora goats) and a waistcoat made of a wool-silk blend known as fustian. The men who appraised Thorpe’s estate noted that he was in possession of a velvet jerkin, a type of sleeveless jacket whose laces would have allowed it to fit snugly. The appraisers proffered that the jerkin was “Mr. Owldsworths,” a reference to Arnold Oldisworth, who arrived at Berkeley Hundred on January 29, 1621, was appointed to the Council of State, and died sometime before July 16, 1621.[38]

Thorpe’s inventory included seven old doublets or close-fitting jackets. Two were made of shamways or chamois and the remainder were fabricated of grosgrain silk or satin. He also had five pair of silk stockings, two pair of linen stockings, and one pair made of worsted, along with a pair of black silk garters and an ample supply of points, metal-tipped laces that would have enabled Thorpe to fasten his clothing.[39] Thorpe’s wardrobe included four pairs of hose plus a pair of old trunk hose (puffed breeches or “pumpkin pants”) that the appraisers disdainfully described as “quite out of fashion.” He also had some enameled spurs. He apparently liked to keep his head covered while he slept, for he owned a decorated nightcap and an old quilted cap. Thorpe also had five Holland caps, headgear made from linen. His attire included a neck cloth and two kerchiefs. The presence of thirty-four falling bands suggests that he had been storing some of the five dozen brought to Virginia as part of the Berkeley Hundred settlers’ supplies.

Thorpe’s household furnishings included a pair of curtains, a bolster, an ample supply of sheets and pillow bears, and cloths for three cupboards. He had custody of two large chests and five trunks, one of which was ironbound and contained documents; two books; Berkeley Hundred’s colors; and bow strings, probably to a longbow or crossbow, both weapons documented archaeologically in early Virginia. Thorpe was credited with utilitarian items such as a copper still, a box of spices, a barrel of tools, fish hooks, sea compasses, and a quadrant. He also had a case of bottles to which Mr. Mathews (probably Samuel Mathews) laid claim and three runlets of a beverage purportedly produced in Virginia, perhaps the artificial wine that the Berkeley settlers were supposed to make or the tasty beer that Thorpe claimed to have made from Indian corn. Also on hand was a runlet of Rosa Solis, or Rosolio, a bright yellow cordial best known as a restorative.[40]

The Berkeley Hundred Settlers at Jordan’s Journey

During the early 1990s, when archaeologists from the James River Institute for Archaeology undertook excavations at Jordan’s Journey, they surmised that the remains of a sizable, substantially built early-seventeenth-century dwelling, designated 44PG300 in the inventory of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, was occupied by a relatively large group of people.

Evidence of nearly 150 early-seventeenth-century ceramic vessels was found at 44PG300. According to curator Beverly Straube, most were English and continental earthenwares. Stoneware from England and Germany made up more than one fifth of the total number of vessels, and there were numerous containers used for food service and beverage consumption. Fragments of Dutch, English, Portuguese, and Spanish coarseware storage jars, milk pans, butter pots, and cooking vessels were found in abundance and constituted nearly half of the ceramic vessels that were recovered. Iberian olive jars and Italian earthenware costrels were present, along with German blue-and-gray stoneware jugs from the Westerald region and brown stoneware from Frechen. Archaeologists also found pottery that had been produced at Jamestown, perhaps by Martin’s Hundred potter Thomas Ward or one of his apprentices, who temporarily withdrew to Jamestown Island after the 1622 Indian attack.[41]

A nearly complete Portuguese tin-glazed cup was found at 44pg300 along with fragments of several delftware drug jars, chargers, plates, and dishes (see fig. 9). A Chinese export porcelain wine cup was unearthed that dates to the first quarter of the seventeenth century. A rarity in its day, it would have been owned by someone of elevated social status. Surprisingly few of the ceramic vessel fragments found at 44PG300 are associated with food consumption, perhaps because most of the site’s occupants used pewter plates or treen, evidence of which rarely is recovered during archaeological excavations.[42]

Because slipware from Somerset County, England, was present in abundance at 44PG300, archaeologist Taft Kiser has surmised that the site’s occupants were recent arrivals from the Bristol area of England. Most of the Society of Berkeley Hundred’s settlers disembarked from Bristol, in southwestern England, and the Society’s principal investors were based in nearby Gloucestershire.[43] Thus, archaeological and documentary evidence suggests that when the settlers took refuge at Jordan’s Journey in the wake of the 1622 Indian attack, they lived communally at 44PG300.

Conclusion

The manifests of the ships Margaret and Supply reveal that the Society of Berkeley Hundred tried to anticipate their servants’ and tenants’ needs in Virginia. However, conspicuously absent from the manifests were any references to the personal belongings that Berkeley Hundred’s gentlemen and their families brought to Virginia. George Thorpe’s inventory reveals that his lifestyle was commensurate with his social status, for he had possession of an abundance of clothing, curtains, bedding, and case furniture, along with some porcelain dishes, a gilded bowl, some pewter porringers, a silver cup, and several silver spoons.

The few mentions of ceramics in Thorpe’s household inventory, though vague, offer an important snapshot for ceramic historians. The listing of “6 litle pursline [porcelain] dishes” is probably the earliest documentary confirmation of Chinese porcelain in Virginia and possibly all of the North American colonies. The “6 small platters & 2 sawcers” are most likely English earthenwares, as are the “2 pie plates, 2 deepe dishes.” When examined in the context of the inventory document, ceramics appear to occupy a meager position in the Thorpe household. However, the fuller picture of ceramic usage in early Virginia is clearly dependent on archaeology for understanding the universe of fragile ceramics which rarely survive the passage of time. Curators of seventeenth-century “period rooms” should take particular note of the culturally diverse profusion of color, pattern, and form represented in the cosmopolitan ceramics assemblages of early Virginia. When both historical and archaeological evidence are combined, it is clear that early Virginia colonists had a rich and varied material culture in what is sometimes perceived as a monochromatic frontier existence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the kind assistance of Taft Kiser, who drew on his considerable knowledge of early Virginia archaeology. We also thank Dee DeRoche, chief curator, Virginia Division of Historic Landmarks, and Carol Marks Bowman, executive director of the Prince George Historical Society. We are indebted to Joseph P. Gromacki for arranging photography of objects from his collection.

Lothrop Withington, Virginia Gleanings in England (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1980), p. 73; Eric Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe and the Berkeley Company (Gloucester, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1982), pp. 33–36; Alexander Brown, The Genesis of the United States, 2 vols. (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1890), 2:1031.

Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, pp. 36–38, 42–43, 48–49; British Archives, London, Public Record Office (hereafter PRO), Class: Court of Exchequer 407, fols. 37, 41; John Smyth of Nibley Papers, New York Public Library, Manuscript Nos. 14–16 (microfilm, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia); Susan M. Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company of London, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1906–35), 1:332.

She may have produced two short-lived sons, John and Richard, who were baptized at St Martin-in-the-Fields, her home parish, on January 28, 1602, and October 6, 1603, respectively. Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, p. 43.

Ibid., pp. 43–45, 50 n. 31, 56; Philip Barbour, ed., Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, President of Virginia and Admiral of New England, 1580–1631, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 2:282–83, 370.

Smyth was steward of the “Hundred and Liberty of Berkeley,” whose focal point was Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire (Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, p. 18). All four Society members were Gloucestershire men.

The boy may have been one of the natives Sir Thomas Dale brought from Virginia in 1616 aboard the ship that also carried Pocahontas and John Rolfe. In 1904 Lothrop Withington noted that on September 19, 1619, a Georgius Thorpe was baptized at St Martin-in-the-Fields. When he was buried on September 27, he was identified as a “Homo Virginiae,” or man of Virginia (Withington, Virginia Gleanings, p. 75).

Brown, Genesis of the United States, 2:1005; Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:130–34, 136.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 1:332, 336, 347, 371, 375, 379; 3:138–39, 148, 151, 193–96, 199–201, 207–10, 374, 240; 4:185

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:178–86. While at sea, the food for the ship’s passengers would have included limited amounts of dried fish, ship biscuits (hardtack), butter, cheese, peas, oatmeal, oil, vinegar, and perhaps pork. In addition to water, they would have consumed beer and cider (Ferrar Papers Manuscript No. 210 [microfilm, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia]).

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:109–14, 197–99, 210–11, 213, 230.

Ibid., 3:130–34, 196, 199–201, 207–10, 375, 403.

Ibid., 3:122–29, 305, 377, 448–49; Ferrar Papers, Manuscript No. 194; Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, pp. 33–34.

He probably was referring to despondency, a malady exacerbated by malnutrition.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:417–18; Ferrar Papers Manuscript No. 322.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 1:382; 3:134, 271–74, 289–91, 293, 367–68, 374–81, 393–96.

Arnold Oldisworth, a gentleman and kinsman of George Thorpe, disembarked at Berkeley Hundred and stayed on. Martha W. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), p. 522.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:385–94, 396–406, 410–11, 426; Barbour, ed., Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, 2:20–21.

McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, p. 540.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:446–49, 469.

Ibid., 3:470.

Ibid., 3:462, 470, 583–84; Barbour, Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, 2:287, 293; Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 43.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:553.

Colonist William Caps, a hardliner who tended to be bombastic, blamed George Thorpe’s soft-heartedness for the Indian attack. Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 4:76.

Barbour, Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, 2:294; Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:552–53, 555, 567. Thomas Thorpe, a Society of Berkeley Hundred tenant killed at Berkeley Hundred, may have been one of George Thorpe’s kinsmen.

Barbour, Travels and Works of Captain John Smith, 2:301; Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 3:612, 652.

Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, p. 277; Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 3; McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, pp. 152–53, 211, 298, 325–26, 357, 494, 531, 568, 636.

Kingsbury, Records of the Virginia Company, 4:246.

Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, pp. 246–49; Virginia Land Office Patent Book 1, Pt. 1, p. 410; Smyth of Nibley MS 41, 42.

PRO Class: Chancery 142/395 f 107; Exchequer 133/155; Gethwyn-Jones, George Thorpe, pp. 266–68.

Assembly minutes and court records for 1623 and 1624 are fragmentary. However, they reveal that after the devastating Indian attack in 1622, Virginia officials focused on the colonists’ safety and security and tried to weaken the natives by undertaking systematic retaliatory raids. In addition to the turmoil that resulted from the native assault, another destabilizing change occurred: revocation of the Virginia Company’s charter.

When Eric Gethwyn-Jones examined Thorpe’s inventory in 1982, he questioned the April 10, 1634, date assigned by its transcriptionist, Council Secretary Benjamin Harrison or his clerk. More recent research establishes April 10, 1624, as the correct date. On March 10, 1624, Sir George Yeardley was ordered to have the estate appraised. The General Court convened in early April 1624 and had adjourned by April 17. Afterward, Thorpe’s estate was settled. Moreover, by 1634 Sir George Yeardley and all three of the three men who had appraised Thorpe’s estate and signed the inventory were dead. Gethwyn-Jones, George Thorpe, p. 218; William W. Hening, ed., The Statutes At Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, 13 vols. (Richmond, Va.: Samuel Pleasants, 1809–23), 1:120–21; McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, pp. 135, 531, 631, 774.

Biggs died in 1626, Sharpe and Yeardley in 1627, and Palmer died in 1629. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, pp. 135, 531, 631, 774.

Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 43.

H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Minutes of Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia (Richmond, Va.: The Library Board, 1924; Library of Virginia, 1979), pp. 11, 17–18; Hening, The Statutes At Large, 1:120–21; Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 43.

McIlwaine, Minutes of Council, pp. 36, 40, 47–48, 73–74; Peter Wilson Coldham, The Complete Book of Emigrants, 1607–1660 (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987), p. 118. Traditionally, a decedent’s greatest creditor was named his administrator.

William Thorpe was baptized in his infancy at Berkeley Church on September 2, 1612, and in 1634 would have just come of age. His mother, Margaret Harris Thorpe, made her will on June 29, 1629, and died sometime before February 1630. She made bequests to her three living children: sons William and John and daughter Margaret. Gethyn-Jones, George Thorpe, pp. 56, 269.

Ten ells (or roughly 10 1/2 yards) of taffeta sarcenet, a soft silk, were included in the manifest of the Margaret, raising the possibility that Thorpe’s cloak was made in Virginia, perhaps by Berkeley Hundred tailor Christopher Bourton.

Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 43; McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, p. 522.

Laces fastened a man’s breeches through holes in his doublet that permitted the shiny aglet tips to dangle on the exterior.

Smyth of Nibley Manuscript No. 43. Rosa Solis was made from a mixture of sundew (an insectivorous bog plant), aqua vitae, and hot, provocative spices (like cubebs, grains of paradise, and galingale) that had been blended together and then distilled. When cordial waters first arrived in England during the late 1400s, they were considered medicinal and were supposed to invigorate the heart and revitalize the spirits. Rosa Solis gained popularity in social situations and, according to seventeenth-century writer William Salmon, “stirs up lust.” In fact, in Salmon’s day it was used at banquets as an accompaniment to lascivious food items (www.historicfood.com/rosolio.htm).

Tim Morgan et al., Archaeological Excavations at Jordan’s Point: Sites 44PG151, 44PG300, 44PG302, 44PG303, 44PG315, 44PG333, 2 vols. (Williamsburg, Va.: Virginia Company Foundation, 1995), pp. 193–234, 236; McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, p. 719.

Beverly A. Straube, Finds from Jordan’s Journey, A 1620–1635 Settlement in Prince George County, Virginia (Richmond, Va.: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1996), p. 52; Morgan et al., Archaeological Excavations, p. 246.

Robert Taft Kiser, “The Ceramics Missed by the Muster: Jordan/Farrar 44PG302, 1620–1635,” manuscript on file, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, 1994, p. 39; McCartney, Virginia Immigrants, p. 63.