Dish (one of a pair), China, 1715. Porcelain. L. 12 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Thomas M. Mueller.) Famille verte enamel decoration with the arms of Edward Harrison (1674–1732) and his wife, Frances Bray (1674–1752). This armorial dish shows no visible gold or silver application except for the five golden arrowheads on the cross on the left side of the armorial.

Dish (one of a pair), China, 1715. Porcelain with visible gold and silver application. L. 12". (Courtesy of the late Khalil Rizk of the Chinese Porcelain Company; photo, Chinese Porcelain Company.)

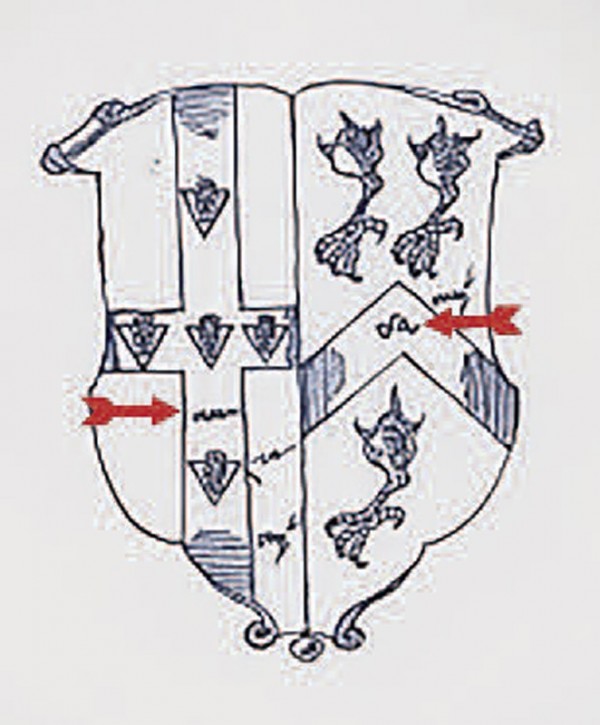

Armorial drawing of the first Harrison and Bray service ordered prior to 1715. Adapted from Clare Le Corbeiller and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Chinese Export Porcelain,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 60, no. 3 (2003): 18.

Vestiges of gold identified using Intensive Surface Analysis on the dish illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Matthew Bunney and Shirley M. Mueller.)

Vestiges of silver identified using Intensive Surface Analysis on the dish illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Matthew Bunney and Shirley M. Mueller)

For some time, there has been an unanswered question regarding a specific Chinese export porcelain service. The 1715 armorial porcelains made in the famille verte style for Edward Harrison (1674–1732) and his wife, Frances Bray (1674–1752), appear to have two variations in the decoration.[1] On the dish illustrated in figure 1, the quadrants created by the blue enameled cross are blank and without color; the right side of the armorial has a brushed yellow ground. In the dish shown in figure 2 gold application is clearly visible in the quadrants of the cross as is the addition of silver on the right side.[2]

After Shirley Mueller studied errors made on Chinese export porcelain, she wondered whether the lack of gold and silver on the service pieces was a mistake of production.[3] That is, silver and gold were meant to be applied but the service was sent out before it was ready, possibly because of inadequate instruction on the part of the agent in charge of the arrangements (who is known as the supercargo) or possibly due to time constraints that prevented putting the finishing touches on some pieces. Others, however, maintain that the unembellished porcelains were handled significantly enough during their period of use so that the silver and gold were rubbed off.[4] After all, the metals were the last to be applied in the process of decoration and were either low-fired or not fired at all.

Whether the cause was wear or mistake is especially relevant for the Harrison and Bray service. The original order, made before 1715, included instructions for colors to be painted on the cross (left) and inverted V (right) using heraldic language in the form of text abbreviations on the armorial itself. The order, however, was executed in underglaze blue and the instruction for colors were made part of the design as seen in figure 3. The “sa” (designated in fig. 3 by the red arrow on the right) stands for “sable,” or black, and the barely legible “argt” (designated by the red arrow on the left) stands for “argent,” or silver. The Chinese clearly did not understand the meaning of the text, which was written in English, and simply copied the design that they were given.[5]

Within a few years the service was reordered by the family in the famille verte palette, and it was hoped that color errors would be rectified. In many existing examples of the Harrison and Bray famille verte service, the cross decoration and inverted V are correctly executed (see fig. 2), but the absence of silver and gold on some of the armorials suggests that errors continued to be made, at least in part. The purpose of this paper is to make a definitive determination regarding this question.

The plain pair (see fig. 1) was examined with both the naked eye and an 8X loop, and neither silver nor gold was visible. The gold and silver on the adorned platters in figure 2, however, were easily seen with the naked eye.

To expand the investigation, the Ceramics Trace Model Study Method (CTMSM) was employed, though used in a manner different from its initial application.[6] As described by its originators, the technique was designed to distinguish Chinese porcelain hundreds of years old from more recent examples.[7] This is accomplished by focusing through the glaze of the ceramic piece in question using a high magnification (500X) digital Dino-lite microscope connected by a Universal Serial Bus (USB) to a laptop or desktop computer. The procedure is not destructive and consequently there is no residual damage to the examined ceramic.

In this study, however, the analysis was of the surface of the porcelain, not within the glaze. We call this adaptation of the CTMSM “Intensive Surface Analysis.” Our purpose here was to determine whether residual silver or gold decoration existed on top of the glaze of Chinese export porcelain when it cannot be seen using the naked eye or an 8X loop.

Scanning the porcelains with and without silver and gold decoration with the hand-held microscope at up to 500X magnification produced a series of images that we recorded and compared. The photographs (figs. 4, 5) revealed that traces of both gold and silver adhered to the surface of the pair of plain pieces in the same areas in which the adorned porcelains show the metals.

Our findings indicate that gold and silver were originally applied to the two unadorned platters tested but apparently rubbed off over time. Whether the metals were overlaid in a faulty manner, which thereby contributed to easy surface abrasion cannot be determined with this technique. We can only say that the metals were present originally because vestiges of them remain. No remnants of gold or silver were found outside the areas decorated with these metals on the intact and the abraded platters.

The intact pieces of the famille verte service with the applied metal ornament apparently were not used. For their owners, the armorial Chinese export porcelain pieces must have been primarily decorative.

We conclude that the 1715 Harrison and Bray armorial service was embellished with silver and gold that wore off over time on the pieces that were used and that microscopic remnants of the precious metals are still visible in the appropriate part of the design using Intensive Surface Analysis. This technique is relatively easy to use, can provide important information where the human eye or 8X loop cannot, and is nondestructive. We believe it will become a method of choice for those who seriously examine not only Chinese export porcelain but other porcelain as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Angela Howard for providing her insights into the Harrison and Bray armorial service.

David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain I (London: Faber and Faber, 1974), p. 187.

Shirley Maloney Mueller, “Surface Silver Decoration on Chinese Export Porcelain: A Survey,” Oriental Art 47, no. 3 (2001): 56–64; Shirley Maloney Mueller, “Surface Silver Decoration on Chinese Export Porcelain: An Analytic Approach,” Oriental Art 48, no. 4 (2002): 43–46.

Shirley Maloney Mueller, “Chinese Export Curiosities,” Oriental Art 46, no. 1 (2000): 16–27.

In reference to a pair of famille verte plates (one of which is illustrated in fig. 1) that appeared in Christie’s sale catalog #2404, January 25, 2011, lot 281, Angela Howard noted: “In the catalog the yellow does look somewhat suspiciously bright, so it might be interesting to test it. But there is no doubt that there is general wear all over. . . .” Private communication with the author, February 17, 2011.

Clare Le Corbeiller and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Chinese Export Porcelain,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 60, no. 3 (2003): 18.

Zhou Yong and Zhou Qiang, Survey of Ceramics Trace Model Study (Guangzhou: Nanfang Daily Press, 2013); Zhou Yong and Zhou Qiang, Trace Model Research and Material Evidence Authentication: Yuan Dynasty Underglaze Blue Porcelain (Guangzhou: Nanfang Daily Press, 2014).

Zhou Yong and Zhou Qiang, Survey of Ceramics Trace Model Study; Zhou Yong and Zhou Qiang, Trace Model Research and Material Evidence Authentication.