Presentation pitchers, attributed to Limoges, France, 1855–1859. Porcelain, enamels, and gilt. H. 11 1/2". Gilt inscriptions: on steamer Louisiana “Capt G.W. Russell”; around the foot rim: “FROM THE ALL BE CLUB” (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.) The commission of the pitchers dates to 1859. This view shows the enameled decoration.

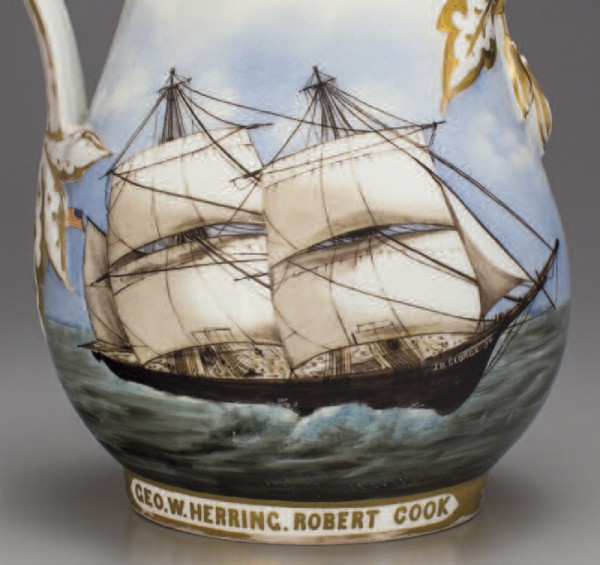

The reverse of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1, with the enameled decoration of the brig James B. George. Around the foot rim is the gilt inscription: (left) “GEO. W HERRING. ROBERT COOK”; (right) “A. J. GEORGE. GEO. M. BOKEE”

Detail showing the inscription on the foot rim of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1: “FROM THE ALL BE CLUB” in gilt block letters.

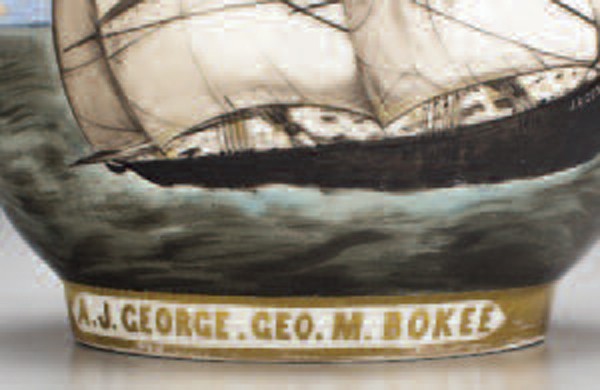

Detail of the inscription on the foot rim of the pitcher illustrated on the left in fig. 2

Detail of the inscription on the foot rim of the pitcher illustrated on the right in fig. 2.

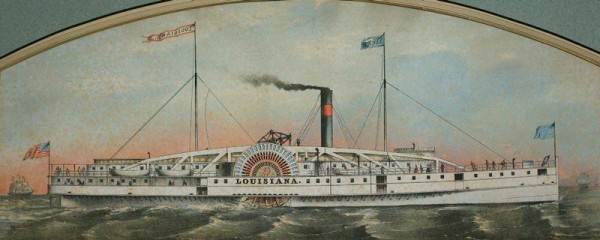

Detail of the steamship Louisiana on one of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1.

Detail of the brig James B. George on one of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1.

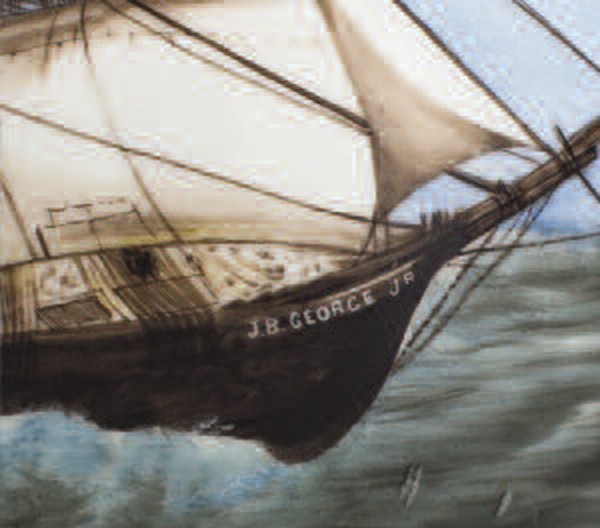

Detail of the inscription on the bow of the brig. Although the inscription reads “J. B. GEORGE JR,” no evidence for this exact name exists, the closest being James B. George, of which in 1859 Captain George W. Russell was a co-owner.

Detail of the molding below the spout of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1. The molding takes the form of a fig leaf with fruit highlighted in gilt.

Detail of the molding of the handle terminal of the pitchers illustrated in fig. 1. The molding takes the form of a fig leaf.

Plate, France or Germany, decorated by Rudolph Lux, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1868. Porcelain, enamels, and gilt. D. 8 7/16". Inscribed: “Sam Montgomery / Master” (Courtesy, The Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase funded by the Houston Junior Woman’s Club.) The steamer is named after the “Celebrated Horse” Dexter, immortalized in an 1867 Currier & Ives print, The King of the World.

Louisiana, unidentified artist, 1850s. Lithograph. 7 1/2" x 19". (Courtesy, The Mariners’ Museum.)

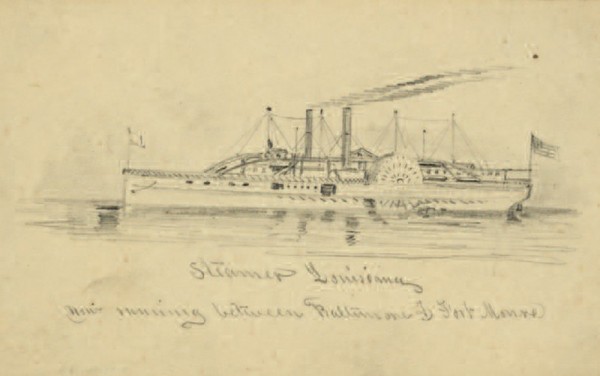

Alfred Rudolph Waud (1828–1891), Steamer Louisiana now running between Baltimore & Fort Monroe, 1861–1865. Pencil drawing on paper. 3 3/8" x 5 3/8". (Morgan collection of Civil War drawings, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.; available online at https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.21373/)

Album quilt, American, Baltimore, Maryland, 1852. Cotton, velvet, silk; silk and/or cotton embroidery threads, ink. 89 3/4" x 88 1/4". (Courtesy, The Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from Gift of Edith Ferry Hooper, The Aaron Strauss and Lillie Strauss Founndation, and Mrs. Frank Kent, and Bequest of Alfred Duane Pell, BMA 1971.36.1.) Presented by the friends of Captain George W. Russell. Designer: Attributed to Mary Simon (née Heidenroder.)

Detail of the album quilt illustrated in fig. 14.

Yesterday morning a committee of the members of the Allbe Club, consisting of Major George W. Herring, Col. Robert Cook, Adjt. A.J. George and George M. Bokee, visited the residence of Capt. George W. Russell, and presented him with a pair of beautiful and costly china pitchers. The vessels were about one foot high, and bear on one side a painting of the steamer Louisiana, which Capt. R. commands, and immediately over it the name of the recipient. The opposite side bears a painting of the brig James B. George under full Canvas. Around the bottoms are placed the name of the club and the parties who presented it. The presentation was made by Major Herring and responded to by Capt. R. After the presentation the company partook of a fine collation, and all seemed highly pleased with the occasion.[1]

For students of ceramic history, this notice, which appeared in the Baltimore Sun on December 8, 1859, might have served as the only record of the “pair of beautiful and costly china pitchers” mentioned within. The preservation of ceramic objects is always highly variable; the probability for the survival of the fragile medium is infinitesimal. In spite of the odds, these attractive porcelain pitchers, which recently surfaced from a tag sale in eastern Virginia, have remained in remarkably good condition (figs. 1, 2). While the particulars of their descent from the hands of their original owner—Captain George W. Russell—are yet to be fully understood, the anonymously decorated pitchers stand as significant examples of early china painting in the American context.

The newspaper article clearly tells us that Captain Russell was commander of the Louisiana. His connection to the sailing vessel James B. George, however, is not stated, but research indicates he was an owner or co-owner of that vessel. Although the inscription on the pitchers gives the name of the brig as “J.B. GEORGE JR,” official records consistently give the name without the suffix.

The members of the “ALL BE CLUB,” as inscribed on the pitchers, were all prominent participants in Baltimore’s china, glass, and crockery trade: Major George W. Herring, Colonel Robert Cook, Adjutant A. J. George, and George M. Bokee. Their connection to Captain Russell is circumstantial. They may have been among his many admirers and friends or, more likely, had direct business dealings with him relating to shipping their wares on the brig James B. George, which called on ports from New York City to New Orleans. Regardless of their relationship with Russell, the All Be Club members are part of the neglected story of the expansive mercantile traffic by American china and glass dealers in the mid-nineteenth century with hubs in Baltimore, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other major cities.[2]

This article examines the contextual evidence leading to the presentation of these pitchers to Captain Russell. Particular emphasis is given to his tenure as captain of the steamship Louisiana and owner of the James B. George. In addition, an effort is made to understand Russell’s relationship with the members of the All Be Club. In general, historical information was hard to come by, the best evidence being provided by newspapers entries, such as the eyewitness statement of the presentation of the pitchers in 1859. These rich accounts are reproduced relatively intact in the discussion that follows.

Description and Historical Context of the Presentation Pitchers

Measuring 11 1/2" in height, the molded porcelain pitchers are of European manufacture, most likely from a factory in Limoges, France.[3] They would have been glazed and fired but left in the white when they arrived at an American decorator shop, ready to be enameled or gilded. After they were decorated, a low-temperature firing would harden the applied enamels and gilt. Each pitcher has marks scratched in the bottom that look like “21” or “Z1”. These marks probably represent a potter’s tally marks rather than a particular manufacturer. Molded fig leaves provide decorative flourishes under the spout and on the handle terminals, in keeping with the Empire style of the 1850s.

Both pitchers include the wording “FROM THE ALL BE CLUB” in gilt block lettering (fig. 3). One of the pitchers has “GEO. W. HERRING. ROBERT COOK” around the foot (fig. 4). The other has “A. J. GEORGE. GEO. M. BOKEE” (fig. 5). Overall, the enamel painting is remarkably intact. Some of the gilding has been rubbed from larges areas of the handles and under the spout, evidence of substantial use at some point.

Contemporary images of the Louisiana would have been available for a decorator to capture its distinctive architectural details (fig. 6). No picture of the James B. George has been discovered, but the brig class of ship was a fairly standard and popular sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts (fig. 7). The lettering on the bow of the sailing vessel is scratched through the black enameling on the hull (fig. 8).

The rendering of the ships is carefully drawn and shaded with black enamels; the white of the porcelain creates form and contrast. The sky is a light blue enamel with soft white clouds painted in. The waves of the sea are executed with hurriedly applied streaks of green, aqua, and black and is the least successful of the otherwise realistic decoration. Bright colors of red, orange, and blue are added to flying flags.

No evidence is seen for an inscription identifying the Louisiana, and no other marks or signatures are presented within the paintings or on the bottom of the pitchers. The application of the gilt lettering and highlighting of moldings on the spout and handle terminals would have been the final step in the decorating process (figs. 9, 10).

It can be a bit daunting to confront an unsigned work of art. However, since most of the pottery and porcelain made before the twentieth century was never marked or signed, it is a common practice for ceramics scholars to establish authorship through the process of attribution. Beyond analyzing the style and materials of the paintings on the pitchers, we can narrow down the possibilities of identity through their historical context.

The decorating of French porcelain blanks was the practice of William Ellis Tucker in Philadelphia in 1826 until Tucker and his partners were able to produce their own porcelain.[4] By the mid-nineteenth century, the importation of European blanks was a common practice by American enamelers and decorating shops. Special orders of elaborately decorated but costly French porcelains could be made through any number of New York City shops. But the same New York shops also decorated imported blanks themselves, often taking custom commissions.[5] The firm of E. V. Haighwout, for example, was among the largest supplier of custom-decorated porcelains in the country. Its work included commissions for two White House services, and it also produced prodigious quantities of custom hotel wares and presentation china.[6] Haviland and Company was another New York firm that imported tremendous amounts of china from its Limoges factories—both decorated and blanks for resale to other decorators.[7]

The Baltimore members of the All Be Club in 1859 were all prominent china, crockery, and glass merchants who made their living by importing pottery and porcelain from British and European sources (for the wholesale and retail trades) and had dealings with numerous American cities. They certainly knew from where and from whom to commission such custom-designed and painted porcelain objects. One connection was suggested by several 1857 newspapers accounts that place George Herring in proximity to the New York partnership of William Underhill and Haviland & Company. Both Herring and Mr. Underhill gave successive speeches at that year’s Convention of Earthenware Dealers’ meeting in Philadelphia.[8]

Established in 1859, the partnership Underhill, Haviland & Co. was a venture with members of the Haviland family who had been importing French porcelain blanks into their New York shops since the early 1840s.[9] The Haviland Company is best known for its factory in Limoges, established in 1853, where it manufactured and decorated a huge variety of patterns for the American market. Prior to that partnership, New York City directories show that William Underhill operated his own china business from about 1848 until 1859.[10]

In preparation for this article, the photographs of the Russell pitchers were shown to several American ceramics historians familiar with mid-nineteenth-century china painting. Several responders suggested that the decoration on the pitchers might be the work of Rudolph Lux of New Orleans. Lux was a German emigrant who had established a New Orleans china shop by 1857. He advertised his wares and promoted his skills using both German and French blanks for his canvas.[11]

The definitive catalog of Lux’s oeuvre has yet to be written. A recent summary by Anthony Peluso reviews Lux’s prolific but brief career citing nearly forty known examples of his work.[12] Lux is especially well known for his portraits of Civil War generals and soldiers; he diplomatically accepted commissions from both the Northern and Southern sides of the cause. Because most of these portraits appear on porcelain tea cups and saucers, the resulting decorations are fairly diminutive. Peluso’s article also lists nearly two dozen objects decorated between 1862 and 1868 with images of steamboats.[13] Without exception the steamships are ones that traveled the Mississippi and its tributaries from New Orleans to the upper reaches of the Midwest.

Lux’s depictions are quite detailed, with accurate rendering of the ships’ architectural features. Virtually all published examples of Lux’s ship portraits have his signature placed somewhere in the composition. A comparison of the paintings on the unsigned Russell pitchers with signed examples of Lux’s steamboats makes an attribution to Lux generally unconvincing (fig. 11). The renderings on the pitchers, while highly detailed, lack his delicacy of line and refinement. And although the enameling is of the same general quality and palette of Lux’s work, the scale is so much larger than what generally appears on his much smaller tea wares paintings.

The Louisiana and the Brig James B. George

The Louisiana was built by the Baltimore firm of Cooper & Butler in 1854 at the cost of $234,197. It is the type of steam-powered vessel known as a “sidewheeler,” with two paddle wheels, one on either side of the hull amidship. It measured more than 266 feet in length, making it the largest wood-hull steamer of its day. The Louisiana was considered the “last word” in steamboat construction, the finest of its type ever to ply the Chesapeake’s waters.[14]

Because of the ship’s great length, a distinctive timber superstructure was required keep the hull from sagging at the bow and stern. Known as “hog frame” construction, stout trusses ran the length of the ship. This frame is clearly visible in an 1850s lithograph of the Louisiana (fig. 12) and a slightly later drawing made during the Civil War (fig. 13). Likewise, the same highly prominent frame, featured on the renderings on the porcelain pitchers, confirms the identity of the Louisiana in spite of the lack of an inscribed name (see fig. 6).

The Louisiana was owned by the Baltimore Steam Packet Company. The term packet originally referenced the mail packets that were transported on a regular basis as part of a contract with the government. The term was applied to any passenger ship operating between designated cities on a regular schedule. In 1858 an advertisement announced that the Louisiana would leave Baltimore daily for Norfolk at 5 p.m. except on Sundays; the fare to Norfolk was five dollars. The Louisiana remained in service until November 14, 1874, when it collided with another steamship and sank.

The James B. George, built in Baltimore in 1856 and listed as 242 tons, was a brig, a classification that was applied to a medium-size sailing vessel intended for cargo. Based on newspaper mentions of its time in various ports, it appears that it would carry anything from passengers to guano.[15] Later newspaper advertisements and registrations show that the George remained active in the early 1860s.[16]

The George is found in the New-York Marine Register of 1858 showing one Captain Atwell as master.[17] More important, however, is the appearance of the name Russell under the column “Owner or Consignees.” This provides the pivotal association with the brig George featured on the presentation pitchers.

The James B. George appears the following year in American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping, 1859 with a Captain Frazier listed as master. This time, under the column “Managing Owners or Consignees,” the entry “Russell & O” implies that Russell was the principal co-owner with one or more partners, but the nature of the business relationships and the merchants involved are unclear.

A clue to these relationships might lie in the name of the vessel. The Woods’ Baltimore Directory, for 1856–57 lists James B. George Sr., designated as a property agent and collector, and James B. George Jr., classified as a mail agent.[18] Both activities are closely tied to the shipping business, particularly the aforementioned connection with mail-packet contracts entered into by the steamship companies.

Captain George W. Russell

George W. Russell was born in 1812 and spent his adult career as a professional steamship captain on the Chesapeake Bay.[19] While his biographical information has been only partially revealed, it is clear that he was a celebrity among the fraternity of steamship professionals. By 1839 he was a captain in the newly inaugurated Baltimore Steam Packet Company, whose fleet of boats made regularly scheduled runs between Baltimore and Norfolk in addition to other local excursions.[20] By 1842 Russell was in command of the steamship Herald, and the company kept a brisk business in the commute between the major ports of the Chesapeake Bay.[21] In 1846 he was in command of the steamer Georgia.[22]

In addition to commuting between cities on the Chesapeake, the Baltimore Steam Packet Company’s ship captains were permitted to charter steamers from the company for pleasure excursions offered to the public. Perhaps this is one reason Russell gained such favor with his following of friends and admirers over the years. One of these pleasure excursion offerings was advertised in the Baltimore Sun on August 28, 1848, as follows:

GREAT ATTRACTION. PLEASURE EXCURSION TO ANNAPOLIS, OLD POINT, RIP RAPS, NORFOLK, PORTSMOUTH, NAVY-YARD, &c. &c.

Captain George W. Russell respectfully informs his friends and the public, that he has chartered from the Baltimore Steam Packet Company the splendid and swift steamer GEORGIA, well known to the public as one of the most commodious, comfortable and seaworthy boats out of Baltimore, and will make an EXCURSION to Norfolk, Old Point Comfort, Rip Raps, Portsmouth, Navy-Yard and big Ship, leaving Baltimore on SATURDAY MORNING, the 9th of September, at 8 o’clock, touching at Annapolis, giving persons an opportunity of enjoying the beautiful scenery of the noble Chesapeake by daylight. Particulars in a future advertisement.[23]

Captain Russell’s status in the packet line continued to grow. In 1852 he was given command of the newly built North Carolina, a “model boat in every respect,” measuring 235 feet in length. By several accounts, Russell was much admired by his friends and colleagues. This private and public admiration is perhaps best recorded by the presentation album quilt made for him by friends and family in 1852 (fig. 14).[24] One of the quilted squares includes an appliqué of a steamboat with smoke billowing from the stacks and a representation of Russell himself with spyglass in hand (fig. 15). Other imagery on the quilt includes symbols that show that Russell was a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), a fraternal order of Odd Fellows founded in 1819 in Baltimore, Maryland. The George surname is tantalizingly included among the names of the presenters included on the quilt, suggesting a possible familial connection to James Sr. and James Jr., the future namesakes of the brig James B. George.

Writing in 1853, William S. Forrest noted in his Historical and Descriptive Sketches of Norfolk and Vicinity that travel by steam packet between Baltimore and Norfolk took a remarkably and comfortably short twenty-four hours. Forrest made special mention of the competence of the captains who commanded these vessels and specifically referenced Russell, who had recently been given command of the North Carolina, the newest ship in the line. In what might have been a foreshadowing of events, Forrest commented on the safeness of the Baltimore Steam Packet Company’s voyages, which were relatively accident-free:

We may remark here, that this line is so well and ably conducted, that accidents seldom or never happen. The boats are very superior, kept in the finest order, and are in charge of officers of long experience, and well-tried skill and judgment. The North Carolina, a very large and splendid new boat, has recently [been] placed upon this line; and, under the able management of Captain Russell, presents unusual attractions to the traveller, who desires to go north by the pleasant and delightful bay route.[25]

Russell’s time on the North Carolina did not last long. In 1854 he was given the helm of the Louisiana. On November 2, the Washington Sentinel reported: “THE NEW STEAMER LOUISIANA,/Captain George W. Russell, is now nearly ready to take her place on the line. She will probably make a trial trip next week to Norfolk—perhaps during the sitting of the Internal Improvement Convention. We would suggest that as a most suitable time.”[26] Her maiden voyage was on November 9, 1854, and went from Baltimore to Old Point Comfort and the Virginia Capes. Upon his arrival in the Virginia ports, friends from Norfolk and Portsmouth presented him with a “magnificent silver speaking trumpet,” a device to call out orders above the din of the steamship’s engines and wheels.[27]

A notice about Russell appears in the Baltimore Sun in 1855 commending his action in assisting two distressed ships encountered on his route in the Chesapeake Bay:

The Steamer Louisiana—This fine steamer, under the command of Captain George W. Russell, reached this port on Saturday morning with a freight of over 1,400 barrels of fruit and vegetables, the latter including potatoes, beans, peas, cymlings, cucumbers, cabbage, &c., added to which were 143 gallons of oysters in cans, packed in ice. There were 85 cabin passengers and 23 forward. Captain Russell reports the ship Susan E. Howell, Captain E. W. Rattle, off Poplar Island, leaking badly; brought the captain up to the city. The ship is from the Chincha Islands, loaded with guano, consigned to Barada & Brather, 97 days. Also, a brigantine off the Wolf Trap, bound up, in distress. The steamer gave every assistance to both vessels, and all may be considered safe.[28]

Although Russell was highly competent and a well-respected steamship captain, his profession was nonetheless filled with inherent difficulties, and accidents did happen. Such an accident was to befall the Louisiana with Captain Russell in command on the evening of February 20, 1858.

On a “bright moonlight night,” the schooner William K Perrin was carrying her cargo of oysters down the Chesapeake Bay when she collided with the Louisiana. Little or no damage occurred to the much larger steamship, but the Perrin was a sailing vessel of just 47 tons; she foundered and was lost. Conflicting claims of right-of-way according to the prevailing rules of seamanship were adjudicated in a well-publicized case heard by the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Maryland. The courts adjudicated Captain Russell and the owners of the Louisiana and held the owners of the William K Perrin responsible for $1,700 in damages, and its master, Charles Odgen, for an additional $173.

The circuit court’s ruling initially kept Russell’s safety record intact; however, the owners of the Perrin appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In lengthy arguments, the circuit court’s decision was reversed and Russell and the owners of the Louisiana were found at fault. The transcript of the case summarily pronounced the Supreme Court justices’ opinion: “[T]he collision in this case, and destruction of the schooner Perrin, was caused wholly by the negligence and inattention to their duties of the officers who navigated the Louisiana, and that the steamboat should be condemned to pay the whole damage incurred by the said collision.”[29]

How the unfavorable decision affected Russell’s career and his relationship with his business associates, passengers, and friends is undocumented. It may have been forgiven as an unavoidable accident, a routine occurrence in the hazards of navigation on the Chesapeake Bay.

What is known is that the pitchers were presented to Captain Russell at virtually the same time the Supreme Court judgment was released, in December 1859. Had the All Be Club guessed wrong at the outcome of the case? Or were the pitchers intended as a show of solidarity and support for Russell? Or perhaps the pitchers were meant to signify a new business venture among partners. But the timing of the release of the court’s ruling and the presentation seems an unlikely coincidence.

The All Be Club

As recorded on the pitchers, the members of the so-called All Be Club were George W. Herring (1820–1897), Colonel Robert Cook (1824–1912), Adjutant Andrew J. George (b. 1828), and George M. Bokee (1831–1905). These four men appear in all the Baltimore city business directories from 1856 to 1859 as glass and china dealers.[30] Earlier advertisements also helped establish the prominence of these individuals as china merchants. In the February 11 edition of the American Commercial and Daily Advertiser, Robert Cook gave notice of a newly established partnership:

CO-PARTNERSHIP NOTICE.

WILLIAM SHIRLEY has this day associated with him ROBERT COOK in the WHOLESALE AND RETAIL CHINA GLASS AND QUEENS-WARE business, which will be continued at the old stand, 11 and 13 South Calvert street, under the name of SHIRLEY & COOK.

Baltimore, February 5th, 1853[31]

On August 29 the same year George W. Herring advertised his importing business in Baltimore: “CHINA, GLASS AND QUEENSWARE. / GEORGE W, HERRING & CO., Importers, No. 7 S. / Charles st.”[32] And on December 23, 1857, the Baltimore Sun published the often mentioned George M. Bokee’s china store’s numerous suggestions for Christmas gifts:

CHINA ORNAMENTS FOR CHRISTMAS PRESENTS.

A large variety, consisting of BOXES, BOUQUET HOLDERS, COFFEES, / COLOGNES, FIGURES, INKSTANDS, MUGS, / TEA AND TETE-A-TETE SETS. / CIGAR STANDS, VASES, / WATCH HOLDERS, &c. &c., / Now displayed at / BOKEE’S CHINA STORE. / No. 41 NORTH HOWARD STREET, / And offered for sale at less than / AUCTION PRICES, / To suit the times / GEORGE M. BOKEE. / No. 41 North Howard street. / between Lexington and Fayette sts.[33]

A notice in the Baltimore Sun, October 7, 1859, is the only other documentation for this group of men:

Annual Meeting of the Crockery Trade.—The annual meeting of the crockery trade was held last night at Allen’s, in Light street, when, after the transaction of the ordinary business, the following officers were elected for the year ensuing: Geo. W. Herring, president; Joseph R. Marston, vice-president; Geo. M. Bokee, secretary; and Col Robert Cook, treasurer. The report of the treasurer showed a balance of $119 in the treasury after paying all the expenses of the past year.—Those matters disposed of, the association sat down to a magnificent dinner, comprising all the luxuries of the season, and to which ample justice was done.

The president made a statement of the rise and progress of the association, and of the “All-be Club,” which has existed for several years, composed entirely of crockery dealers, and of which one of the most worthy members has always held the post of president.

For several hours there was a good time in the interchange of sentiment, and the best feeling prevailed. There were representatives from the trades in Philadelphia and Wheeling, and the enjoyment of the occasion was full. Before the noon of night the company retired, having spent an evening in rational pleasure.[34]

Apparently, the club constituents were a small, ad hoc subset of Baltimore’s crockery dealers, although at this meeting other crockery dealers from Philadelphia and Wheeling, Virginia, were part of the evening’s revelry. Of the four members of the club, A. J. George is the least represented in the historical documents. Wood’s Baltimore City Directory for 1858–59 lists an Andrew J. George as associated with R. Edwards, Jr. & Co.[35] The same directory reveals that Richard Edwards Jr. & Co. were glassware merchants in the city.[36]

George W. Herring appears to have been the most important and influential of the group. Not only was he president of the All Be Club in 1859, but earlier accounts of the Convention of Earthenware Dealers also reveal his considerable standing at a national level. On June 25, 1857, more than 150 representatives from “New York, Baltimore, Boston, Richmond, Pittsburg, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Wheeling, Chicago, and other cities” gathered in Philadelphia at the La Pierre House.[37] The event was reported on in many papers including those in Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia.[38] In every article, Herring was prominently mentioned. The most extensive and fascinating account of the conference was published in the Baltimore Sun on June 27, 1857. This excerpt includes the lengthy and somewhat hyperbolic speech given by Herring with William Underhill co-joining:

The Convention of Earthenware Dealers

The social conference of the Earthenware Dealers’ Board of Trade, of Philadelphia, was commenced in that city on Thursday morning, at the Assembly Building. In the course of the morning a number of invited guests arrived from other cities, especially from New York, Boston and Baltimore. There was no business transacted in the morning. At noon the members partook of a collation, and at 2 o’clock the conference met in private. In the evening the company sat down to a sumptuous banquet at the La Pierre House, to which they were welcomed by the president, Mr. Hacker, in the following appropriate remarks:Gentlemen—The present scene, at least to me, is one of unfeigned pleasure. It is my duty as president of the “Earthenware Dealers,” Board of Trade of the city of Philadelphia—a position not assigned to me because of any talent of speech-making—to stand up and bid you welcome, thrice welcome, to the hospitalities of this social occasion. And I, for myself and my colleagues, now, with open arms and hearts big with the sincerest sentiments of brotherly friendship, do hail you as the guests of our association, and welcome you to the city of brotherly love with a most true and fraternal greeting. We have called our assembling together in this city a social conference of the importers and jobbers of earthenware, china and glassware. Our objects are more of a social and business character. And yet we feel that much good will result from our business meeting of today and at future sessions.

It is no common sight that we witness this evening. Scarcely in the annals of this country, and certainly not in any other, has there been assembled of one branch of trade; on no occasion such as this, so extended a representation. We have here parties representing fifteen States and twenty-four cities of this Union; and we mean to show to the world that the time has come, when, in the fair and active emulation of commendable business enterprise, there need be no want of social and kindly regard—no jealous rivalry that will mar the harmonies of life; and we shall endeavor to obliterate that ugly adage, “that two of a trade can never agree.” This . . . saying [has] long been repudiated as false to our ears[.]

The earthenware trade of the United States, although limited in amount when compared with other departments of trade and commerce, is yet of vast importance to the general interests of the country. It gives the reward of labor to some thousands in the potteries of Staffordshire, England. Its bulk is so great in comparison with the value of the article that it gives employment to large numbers of the laboring classes in this country, in the departments of packing, storing, draying, &c., and it is of vital importance to the shipping interests of the world; for the groundwork of almost every ship chartered in Liverpool for this country, and for other distant places, is crates of earthenware and china[.]

The number of packages of earthenware shipped from Liverpool to the United States for the past six years, averages about 100,000 crates per annum; the entire shipments from Liverpool to all parts of the world average about 170,000 per annum; the United States, therefore, receive more than one-half of all that is exported.

The bulk of 170,000 crates is equal to 212,500 tons measurement, and would load 212 ships of 1,000 each; being four ships per week for all the year. You can see at a glance how important is the manufacture of this article to the shipping interest. And then, gentlemen, the vast amount of freight that it gives to our railroads and canals in this country is equally important, for the revenue from it is very heavy, although the value is insignificant when compared to many other articles that are sold and forwarded to all parts of our continent; yet the freight is paid on bulk weight. The average freight from England to the United States is about 5 per cent on its cost.

The manufacture of earthenware can be traced as far back as the building of the tower of Babel—and it is not now confined to England—it is made in some form in every country on the face of the globe; the Chinese, the Japanese and the French, are now famed for the magnificence of these articles of porcelain; and indeed the French China manufacture is becoming rapidly a great source of revenue to this government, and is now a staple article of use in all parts of the United States.

In his response to a toast in honor of the Baltimore trade, Herring said:

Ever since the formation of our government, the office of president has been looked to as a position to satisfy the highest aspirations of the greatest and most ambitious of our countrymen; indeed, to be called president at any time is honorable, but to be called President of the United States, or president of the crockery trade of a city, I think excels all other worldly attractions, and should gratify the ambitious desires of any man; but position brings with it its necessary burdens, and often overtasks its recipients. This is just the position I find myself in tonight; but as most of the presidents have said, I feel my incompetency for the task imposed upon me, and throw myself upon your indulgence. The Baltimore trade, Mr. President, can but feel highly gratified upon this occasion. Scarcely six months since they conceived and carried out in an humble way the idea of calling together around the festive board the members of the earthenware trade of this city, for the purpose of drawing together the bond of friendship, and to do away with the selfish idea which for many years has been prevalent, that competition and rivalry would always prevent merchants engaged in the same business from ever being upon terms of personal intimacy.—The seed we sowed in weakness, you reap in power; and it is my earnest wish that it may grow up to be a mighty tree, under whose branches the entire earthenware trade of our country may seek shelter. I say again, Mr. President, the earthenware trade of Baltimore feel gratified at the sight which meets their gaze to-night. We feel no jealousy because you have excelled us in the beauty and extent of your arrangements. Would Robert Fulton, were he living at this day, gaze with less admiration on a Collias steamer, because it was an improvement on his own humble efforts; would Benjamin Franklin look coldly on Morse, because he had taken his discovery and applied it to purposes of extended good; would Demaratius, father of Tarquinias Pilaeus, who is said to have instructed the Etruscans and Romans in the art of pottery, had he been living [in] 1730, have cursed that year because it gave birth to Josiah Wedgwood; or would Wedgwood, who patented, in 1763, a style of ware called queensware, feel mortified at the improvement in that article of Edwards, Furunel, Alcock and others of the present day? No, sir, the contrary would have been the effect on all of them. And so it is with us of Baltimore. We not only feel proud of the successful effort you have made to excel, but our wish is that others may excel you, and that the motto throughout our country among earthen dealers shall be Excelsior! Well, sir, we are here with other gentlemen of the trade by invitation, and we throw ourselves upon your mercy; and I am fearful that before we get through we will have to exclaim, “save us from our friends!” The Baltimore trade came here, sir, to have a good time, and as we are only passengers, we place ourselves entirely under your control; and although we expect to travel fast, yet the indications are that we will not be able to keep our seats; and I dread a collision either with a lamp post or a watchman; and if we keep the track we will be quite fortunate—or do not collapse a flue, as there seems to be no taking in water. In conclusion, Mr. President, I beg leave to return the Philadelphia trade the thanks of the Baltimore trade for their kind invitation to participate in this national convention of earthenware dealers, and hope it may redound to the mutual benefit of all present; and although our numbers are small, and means limited, yet we shall be proud to extend to any of our fellow tradesmen an invitation and welcome to the city of monuments.-

Mr. W. Underhill, of New York, responded at some length to a toast, and among other things said—

I think I may say, judging from the activity manifested since we have been assembled around this hospitable board, that the earthenware trade, as represented here is in a very healthy state, and when I see surrounding me the majestic soup tureens (figuratively speaking, Mr. President) the capacious covered dishes, the well filled casseroles, the substantial bakers, the useful as well as ornamental sauce tureens and boats, together with the compotiers, baskets and other elegant dessert pieces of which this set is composed, I cannot but congratulate myself upon the perfect entirety which we present, and can fervently ejaculate—“May we never break!”[39]

Conclusions

The point of embarkation for this article began with the discovery of the elaborately decorated pitchers presented to Captain George W. Russell by members of the All Be Club of Baltimore. The most critical discovery was the Baltimore newspaper account recounting the exact time and day that the pitchers were presented to Russell. From that account, we learn that Russell was the illustrious captain of the Louisiana, the largest and grandest steamboat of the Baltimore Steam Packet Company. We also found that Russell owned or had ownership in the brig James B. George, also depicted on the presentation pitchers.

Subsequent research discovered the identities of the members of the All Be Club recorded on the pitchers as the leading glass and china merchants in the thriving Baltimore trade. A side excursion into the china and glass business revealed the account of the Convention of Earthenware Dealers held in Philadelphia in 1857, which was attended by more than 150 merchants, from many major American cities. The potential for investigating this remarkable event, reflecting the extent and importance of the American ceramic trade network is particularly enticing for future researchers. The identity of the decorator and/or decorating shops, however, remains unknown. In general, the style and quality of the presentation pitchers are in keeping with the output from the china decorating workshops operating in New York City in the mid-nineteenth century. While it is tantalizing to associate the ship portraiture with the work of Rudolph Lux, such a link remains unsubstantiated.

As with many studies of material culture, the stories often begin with an object. While much has been learned on this trial voyage, there is more research to be done. If these pitchers remain anonymous, their aesthetic and intrinsic value alone would still enthrall the historical ceramic community. But it is the continuing stories that are just beginning to be coaxed from these mute objects that will ensure their place among other illustrious examples of mid-nineteenth-century American ceramic art. Where the journey will lead, we cannot know, but it will be a destination that Captain Russell and his friends in the All Be Club would never have imagined on the morning of December 7, 1859.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article benefited from the help and assistance of many people who offered advice, opinions, and supplementary research. Of particular note is Marshall Goodman, who called our attention to these wonderful pitchers. Ellen Denker, Nonnie Frelinghuysen, Anthony Peluso, and Rex Stark provided valuable commentary. Lydia Blackmore, decorative arts curator for The Historic New Orleans Collection, provided access to the collection’s research on Rudolph Lux. Joan Quinn provided additional research in the Baltimore records. Robert Doares was extremely generous in sharing his expertise on Haviland china. Angelika Kuettner was instrumental in obtaining images and permissions for this article. We especially thank Mary Gladue for helping to sort out the disparate story lines and bringing cohesion to the final article.

Baltimore Sun, December 8, 1859, vol. 46, issue 18, p. 1.

George L. Miller and Amy C. Earls, “War and Pots: The Impact of Economics and Politics on Ceramic Consumption Patterns,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 67–108.

Personal communication with Robert Doares, May 11, 2016. Barbara Woods and Robert Doares, Old Limoges: Haviland Porcelain Design and Decor, 1845–1865 (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Pub., 2005).

Ellen Denker and Bert Denker, The Warner Collector’s Guide to North American Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Warner Books, 1982), p. 157.

Woods and Doares, Old Limoges, pp. 23–26.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Empire City Entrepreneurs: Ceramic and Glass in New York City,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 327–54, esp. p. 330.

Woods and Doares, Old Limoges, p. 25.

“The Earthenware Trade of the United States,” Evening Post (New York), June 27, 1857, p. 2.

Woods and Doares, Old Limoges, pp. 22–23.

Trow’s New York City Directory for 1859: “Underhill, Haviland & Co. china, 22 Vesey Street.” I am indebted to Robert Doares for providing this information.

Encyclopaedia of New Orleans Artists, 1718–1918, edited by John A. Mahé and Rosanne McCaffrey (New Orleans, La.: Historic New Orleans Collection, 1987).

A. J. Peluso Jr., “There Was No One Like Rudolph T. Lux, Ever,” Maine Antique Digest, August 17, 2015, available online at www.maineantiquedigest.com/stories/there-was-no-one-like-rudolph-t-lux-ever/5224.

Ibid.

Alexander Crosby Brown, “The Old Bay Line of the Chesapeake: A Sketch of a Hundred Years of Steamboat Operation,” The William and Mary Quarterly 18, no. 4 (October 1938): 389–405.

See, e.g., the following reference, which was published May 20, 1861: “NEW-YORK . . . SUNDAY, May 19. / BELOW — Brig. James B. George, from Rio Janeiro” (online at www.nytimes.com/1861/05/20/news/marine-intelligence-arrived-sailed-miscellaneousspoken-c-foreign-ports.html).

American Lloyd’s Register of American and Foreign Shipping, 1861, available online at http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/SPSearch.cfm?ID=1891.

New-York Marine Register (1858), p. 163 (online at http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/SPSearch.cfm?ID=18868).

Woods’ Baltimore Directory, for 1856–57, vol. 544, p. 125 (online courtesy of Maryland State Archives, http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000544/html/index.html).

Dena S. Katzenberg, Baltimore Album Quilts, exh. cat. (Baltimore, Md.: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1981), p. 116.

Alexander Crosby Brown, Steam Packets on the Chesapeake: A History of the Old Bay Line since 1840 (Cambridge, Md.: Cornell Maritime Press, 1961), p. 26.

Ibid., p. 30.

Ibid., p. 34.

Baltimore Sun, vol. 28, issue 79, August 28, 1848, p. 3.

Katzenberg, Baltimore Album Quilts, p. 116.

William S. Forrest, Historical and Descriptive Sketches of Norfolk and Vicinity (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1853), p. 155.

Washington Sentinel, vol. 3, issue 33, November 2, 1854, p. 2.

Forrest, Historical and Descriptive Sketches of Norfolk p. 39, originally cited in Harry W. Burton, The History of Norfolk, Virginia: A Review of Important Events and Incidents Which Occurred from 1736–1877 (Norfolk, Va.: Norfolk Virginian Job Print, 1877), p. 19.

Baltimore Sun, vol. 37, issue 33, June 25, 1855, p. 1.

Haney v. Baltimore Steam Packet Company, 64 U.S. 287 (1859), on appeal from the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Maryland.

See, e.g., Wood’s Baltimore City Directory, for 1858–59.

American Commercial and Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, Md.), February 11, 1853, p. 3.

Ibid., August 29, 1853, p. 4.

Baltimore Sun, vol. 42, issue 31, December 23, 1857, p. 2.

Ibid., vol. 65, issue 123, October 7, 1859, p. 1.

Wood’s Baltimore City Directory, for 1858–59, p. 179.

Ibid., p. 154.

New York Tribune, vol. 17, issue 50, June 26, 1857, p. 4.

Evening Post (New York), vol. 56, June 27, 1857, p. 2.

Baltimore Sun, June 27, 1857, vol. 41, issue 36, p. 1.