George A. Washington (1732–1799), A Plan of Alexandria now Belhaven [oriented with north to the right], [1749]. Pen and ink on paper. 14 13/16 x 17 15/16". (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

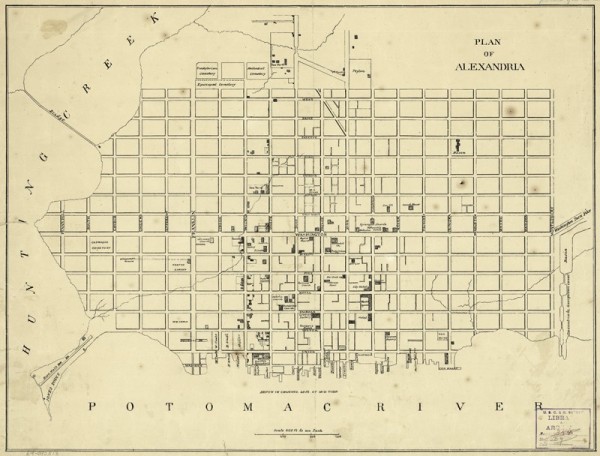

United States Coast Survey, Plan of Alexandria [oriented with north to the right], [1862]. 16 1/8 x 21 1/4". (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.)

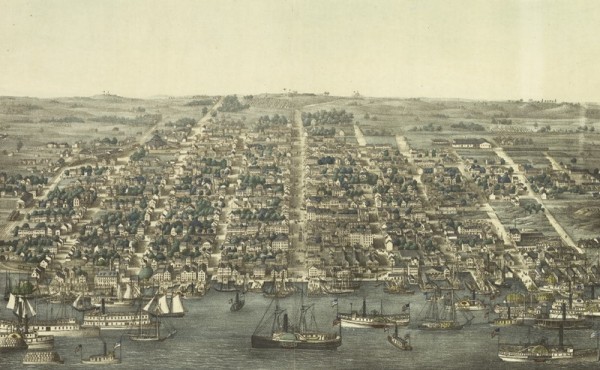

Charles Magnus, Birds Eye View of Alexandria, Va., [1863]. 14 3/16 x 23 1/4". (Library of Congress.)

Modern-day street scene, Alexandria, Virgina, 2001. (Courtesy, Office of Historic Alexandria; photo, Eric Kvalsvik.)

A selection of the ceramics illustrated in this article on a table in the Alexandria Archaeology Museum, 2017. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Native American pottery fragments, Early Woodland period, ca. 900–300 B.C. Low-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) These very small fragments are typical of prehistoric pottery found in Alexandria excavations. This type of pottery is known as cord-marked Accokeek ware.

Native American vessel, Early Woodland period, ca. 900–300 B.C. Low-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Joint Base-Anacostia Bolling [JBAB], Naval District Washington and Maryland Archaeology Laboratory, Jefferson Patterson Park.)

Dish fragments, Portugal, ca. 1660–1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments of Portuguese majolica were found among piles of ship’s ballast that had been dumped beside the Carlyle-Dalton Wharf.

Dish, Portugal, ca. 1660–1680. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 14 5/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) An example of the type of Portuguese dish represented by the fragments illustrated in fig. 8.

Lidded cooking pot, Rouen, France, ca. 1740–1790. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Known as the Rouen Plain type of faïence brune, this ware is typically associated with French-occupied sites in North America.

Pitcher, Rouen, France, ca. 1740–1790. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.)

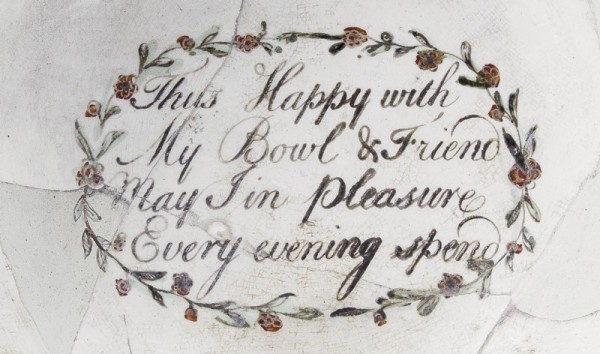

Punchbowl, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1770–1780. Creamware. D. 7". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Decorated with a polychome rose-and-floral pattern and verse. Found at Arell’s Tavern, this bowl would have held a quart of punch. Inscribed on interior bottom: “Thus Happy with / My Bowl & Friend / May I in pleasure / Every evening spend.”

Detail of the verse inside the bowl illustrated in fig. 12.

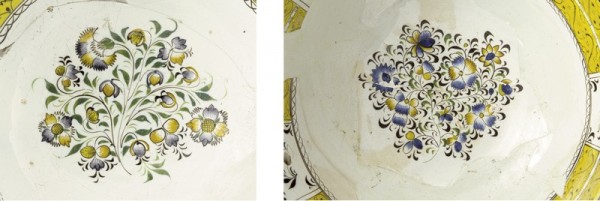

Punch bowls, Wood & Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1795–1815. D. (left) 9 1/2", D. (right) 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Recovered from McKnight’s Tavern, these large bowls would have held a half-gallon and gallon of punch, respectively.

Details of the rim designs on the punch bowls illustrated in fig. 14.

Details of the interior designs on the punch bowls illustrated in fig. 14.

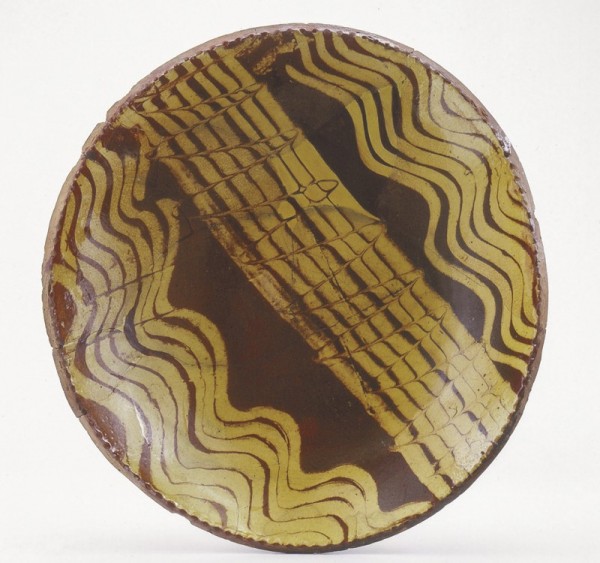

Pan, Henry Piercy, Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1792–1796. Slipware. D. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Dish, Henry Piercy, Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1792–1796. Slipware. D. 13". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

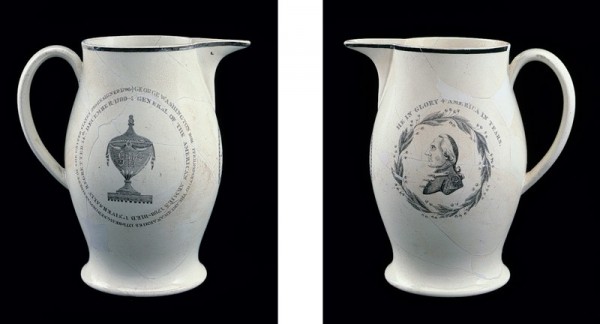

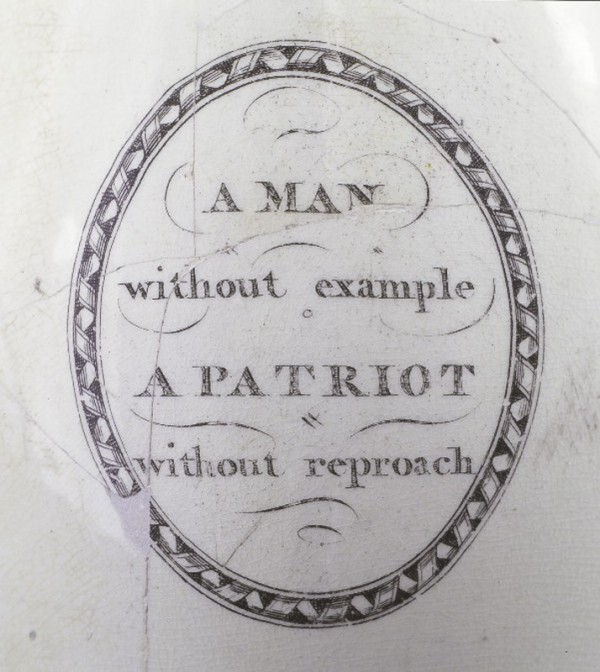

Pitcher, attributed to the Herculaneum Pottery, Liverpool, England, ca. 1800. Creamware. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This black-rimmed mourning pitcher depicts Washington in profile surrounded by a wreath above which are the words “HE IN GLORY • AMERICA IN TEARS.” On the reverse is an urn with the initials GW and the words “GEORGE WASHINGTON BORN FEB. 11, 1732 / GEN’L OF THE AMERICAN ARMIES 1775 / RESIGNED 1785 / PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 1789 / RESIGNED 1796 / GENERAL OF THE AMERICAN ARMIES 1798 / DIED UNIVERSALLY REGRETTED 14TH DECEMBER 1799.” Under the spout are the words “A MAN / without example / A PATRIOT / without reproach.”

Detail of the mourning pitcher illustrated in fig. 19.

Chamber pot, attributed to Ferrybridge & Co., Yorkshire, England, ca. 1796–1801. Creamware. D. 8 1/4". Marks: stamped “WEDGWOOD” and “3” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Banded and sponged. Two of these pots were found together in the same privy, at an apothecary shop, where they were deposited around 1800–1820 along with eight plain creamware chamber pots.

Spill vase, probably Yorkshire, England, ca. 1820. Pearlware. H. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Found in a privy probably associated with Gadsby’s Tavern.

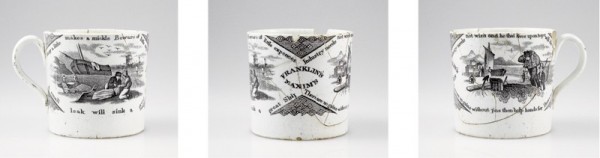

Child’s mug, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1820–1850. Whiteware. H. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Alexandria Archeology Museum; photo, Robert Hunter.) Crudely applied transfer prints depict a shipwreck with “Franklin Maxims”: “Many a little makes a mickle. Beware of little expense”; “A small leak will sink a great ship”; on the reverse, maxims for people performing chores: “Industry needs not wish and he that lives upon hope will die fasting”; “There are no gains without pins [pains] then help hands for I have no lands.” From Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac, first printed in 1732.

Milk pan, Benedict Milburn, Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1831–1847. Salt-glazed stoneware, brushed cobalt. D. 10". Capacity: 1 gallon. Mark: impressed “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA / D.C” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The milk pan was discarded in a privy at 106 South St. Asaph Street in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Jar, Benedict Milburn, Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1847–1861. Salt-glazed stoneware, slip-trailed cobalt. H. 14 1/2". Mark: impressed “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA” (Courtesy, Alexandria Archaeology Museum; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This elaborately decorated jar was found in excavations at a nineteenth-century free-black neighborhood at Alfred and South Columbus Streets.

The town of Alexandria, Virginia, was built on the site of a 1730s tobacco trading post established by Scottish merchants and tobacco farmers, although these English-speaking people were not the first to live on the land. Evidence of Native Americans occupation has been recovered from Alexandria dating as early as 11,000 B.C. Although most prehistoric habitations of the area appear to be transient tool-making sites, at least one more permanent Late Woodland–period settlement has been identified.[1]

The formal town plan was established in 1749 on bluffs above a half-moon bay (fig. 1). Over the next few decades town leaders engaged in massive earthmoving operations to develop a deep port by cutting down steep bluffs and filling shallow mudflats around the wharves. A public warehouse built on the waterfront in 1755 was discovered in excavations in 2015, along with a ship scuttled in the landfill. By 1790 Alexandria was the principal port on the Potomac and the seventh largest port in the United States, with nearly 1,000 ships docking annually. Its wharves hosted ships engaged in both the coastal trade and in trade with Europe and the Caribbean.[2]

Alexandrians basked in the glow of their illustrious neighbor George Washington during his lifetime, mourned his passing, and continue to celebrate his association with the town with parades and Birthnight Balls. Washington dined, danced, and attended meetings at Alexandria’s taverns, and may have been served from punch bowls found by archaeologists.

Henry Piercy, Alexandria’s preeminent earthenware potter, had served as an aide-de-camp to Washington before moving to Alexandria. Both men were members of Alexandria Lodge #22, and Piercy led the Alexandria Blues, a privately outfitted militia, at Washington’s funeral. Fragments of Piercy’s earthenware have been found at the Washington household at Mount Vernon.

In 1791 Alexandria was incorporated into the District of Columbia, along with Washington City and Georgetown. Unfortunately, Alexandria’s inclusion in the Federal City, the Jeffersonian Embargo of 1807, and the War of 1812 all had a devastating effect on its economy. In the 1840s recovery was helped by the opening of the Alexandria Canal and by Alexandria’s retrocession to Virginia, but it was not long before the Civil War and Union occupation dealt another heavy blow. The town did not regain its prominence or its former prosperity until recent decades.

Enslaved people in Alexandria often lived in their masters’ households, but, as in other urban areas, some lived in rented homes with other slaves and free blacks. Notably, Alexandria also had a sizable free black community, as recorded in the 1790 Federal Census, and several neighborhoods formed over the next decades. Churches and social and fraternal organizations served the community. A school for black children was formed in 1815. The community included skilled artisans such as builder George Seaton and stonework potter David Jarbour, who worked with Benedict C. Milburn.

In January 1827 a fire swept through the town, destroying many wooden buildings and damaging more substantial brick houses.[3] In the middle of the nineteenth century, Alexandria was home to the largest slave-trading operation on the East Coast but during the Union occupation in the Civil War, the town provided sanctuary for large numbers of African-Americans fleeing Southern plantations. After the Civil War and federal occupation, Alexandria struggled to return to normalcy and prosperity. As the industrial era emerged, Alexandria became home to larger businesses, among them a brewery, glassworks, a shipbuilding company, and a train yard, all of which have been explored archaeologically (figs. 2, 3). For much of the twentieth century and into the present day, Alexandria has been inhabited by many federal government employees.

Successful historic preservation efforts have helped retain the town’s history and character (fig. 4). Archaeology became a part of city government in 1973, and today a local archaeological-preservation law ensures that we will continue to learn about important aspects of Alexandria’s history.

City archaeologists in Alexandria curate a collection of more than two million artifacts from more than fifty-five years of research and excavations. These artifacts were recovered from prehistoric settlements and tool-making sites, nineteenth-century free-black and slave households, slave-trading establishments, industrial and manufacturing sites, a canal, and Civil War camps and fortifications. Of particular note are the rich assemblages recovered from deep brick-lined wells and privies during urban renewal projects in the 1960s and 1970s. Current work revolves around a plantation site, a post–Civil War African-American settlement, and early sites on the Alexandria waterfront.

What follows below is a presentation of ten significant ceramics stories from Alexandria archaeological collections. Some of these objects are beautiful, some are quirky, but all help to tell the story of Alexandria. These are our favorites today, but tomorrow, who knows? We eagerly await new discoveries from the redevelopment of the Alexandria waterfront and throughout Alexandria.

Prehistoric Pottery

Native Americans first passed through this area at least 11,000 years ago, when a toolmaker broke and discarded a Clovis point found in 2007 at the site of Freedmen’s Cemetery, but it was not until the Early Woodland period that people began to manufacture and use pottery.[4] Early pottery use coincides with an increased use of seed plants, which eventually led to the Late Woodland period, a transition from nomadic hunters and gatherers to more sedentary agriculturalists.[5]

In Alexandria, evidence of prehistoric pottery use is scarce because of poor preservation. Much of the porous, low-fired pottery has not held up well here, where fragments were subjected to repeated moisture and drying, freezing and thawing. Often we find just small fragments of clay with shell temper, hardly recognizable as pottery because the surface has worn away.

Fragments of so-called Accokeek pottery (900–300 B.C.) were found at the Stonegate site in the western part of Alexandria (fig. 6). Accokeek pottery, named for a site in Maryland, is tempered with sand or with crushed quartz with a cord-marked surface. The potter created the cord markings by pressing a paddle wrapped with rope against the wet clay surface; the markings usually slant down from the rim to the right, reflecting the way in which the pot and paddle were held. These pots are coil-formed and have conical or rounded rims, as seen in the more complete example illustrated in figure 7.[6]

Ballast and Early Shipping

In 1982 a corner of the Carlyle-Dalton Wharf was discovered during construction of a condominium. Two of Alexandria’s founders, John Carlyle and John Dalton, had built the 200-foot-long wharf at the base of Cameron Street in 1759, extending out toward the deeper channel.[7] Both men owned large homes on the bluffs above the wharf. In the late eighteenth century, the high bluffs were knocked down and the shallow bay was filled to bring the shoreline closer to the deep channel. By the end of the century the shoreline was similar to that seen today, and the Carlyle-Dalton wharf was covered with earth, a block inland from the Potomac River.[8]

The Alexandria Archaeology Museum conducted brief rescue excavations at the site, near the corner of Cameron and Lee Streets. Next to the mid-eighteenth-century wharf structure, archaeologists found a few hundred pieces of pottery. Most of the ceramics were water-worn and predated the wharf, and Alexandra’s founding, by more than fifty years.

In the silt beside the wharf timbers, archaeologists found rose-head nails, gunflints, and small fragments of water-worn ceramics. Many of these sherds were identified as Spanish and Portuguese wares from the third quarter of the seventeenth century (figs. 8, 9).[9] Initially we thought these earlier seventeenth-century Iberian storage jars and majolica fragments had been included in the ballast on European ships that visited Alexandria in the mid-eighteenth century. It is possible, however, that they are evidence of ships trading with earlier settlers in the vicinity before Alexandria was established.

French Faience

Eighteenth-century French pottery is found in northern parts of North America, where there were French settlements, but it is less common in the Mid-Atlantic region. Nevertheless, archaeologists have recovered a few examples in Alexandria, including two nearly complete vessels of faïence brune of the Rouen Plain type, ca. 1740–1790. Commonly known as Rouen faience, this ware is noted for having a dark-brown lead-glazed exterior with a white or bluish tin-glaze interior.[10]

In Alexandria we found a lidded cooking pot and a pitcher in two features that served as wells and/or privies excavated during the Urban Renewal project. The large cooking pot illustrated in figure 10 could be mistaken for a modern example but was found along with other artifacts from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries at the site of Arell’s Tavern, which was built in 1762. The pitcher illustrated in figure 11 was recovered in another privy a block away that is associated with 1790s cabinetmaker Joseph Muir.

Were these vessels brought to Alexandria by English settlers or by French immigrants? Or did an Alexandria merchant receive a shipment of French ceramics along with wine and fancy goods? Historical records are scant, and this will remain one of our archaeological mysteries.

Festivity at Arell’s Tavern

“Thus Happy with / My Bowl & Friend / May I in pleasure / Every evening spend” is the lovely sentiment enameled on the bottom of a creamware punch bowl excavated at the site of Arell’s Tavern (figs. 12, 13). This evocative artifact is one of about 10,000 thus far recovered from tavern sites in Alexandria. Punch was served either hot or cold and might include rum or brandy, citrus juice, fortified wines, refined loaf or brown sugar, and water. It was served in large punch bowls and ladled into glasses, or might have been sipped from smaller punch bowls that were passed around.

Arell’s Tavern, built about 1762 on an alley on the Market Square, is the earliest of the five tavern sites excavated in Alexandria.[11] George Washington’s diaries show that he dined there frequently between 1764 and 1774. On July 5, 1774, George Washington, George Mason, and others met at Arell’s to develop the Fairfax Resolves, the precursor of the Bill of Rights. Perhaps those illustrious tavern patrons drank from this punch bowl.

It is possible that Arell’s Tavern survived into the twentieth century, but the history of the building on the site was in dispute and it was torn down during the 1960s Urban Renewal project. Archaeologists excavated four deep brick-lined features associated with the tavern. Two of them, used as privies and trash pits, were rich with artifacts from the mid-eighteenth century through the 1820s. Archaeologists found more ceramic drinking vessels here than at other Alexandria sites, including fifty punch bowls of various sizes and forty-seven tankards.

Wood & Caldwell Pearlware Punch Bowls from McKnight’s Tavern

Built around 1775 one block from Arell’s Tavern, McKnight’s Spread Eagle Tavern was used for meetings of the local Masonic Lodge as well as for private parties, meetings, and entertainments. Archaeologists have found forty-four punch bowls and thirteen tankards in privy/wells associated with this tavern, including two large, beautifully painted pearlware punch bowls with distinctive yellow borders (figs. 14-16).[12] They found small fragments of similar pearlware punch bowls at both Arell’s Tavern and two nearby homes, along with matching teacups and saucers in a related pattern.

In 2006 the late ceramicist and researcher Don Carpentier had the opportunity to excavate part of a waster tip at a pottery in Burslem, England. He dated the excavated area to 1795–1805 based in part on a coin found among the wasters and in part on the fact that the Burslem firm of Wood & Caldwell had occupied the site from 1790 to 1818. Fortunately, he was able to bring the collection of pearlware and creamware fragments back to his Eastfield Village, outside of Albany, New York, for comparison with American archaeological assemblages. These fragments provide the basis for identifying the probable makers of the Alexandria pearlware examples as the firm of Wood & Caldwell of Burslem, Staffordshire.[13]

Henry Piercy, Alexandria Potter and Promoter of Domestic Manufacture

Henry Piercy was the best known of Alexandria’s earthenware potters. Like many of the early American potters, the Piercy family came from the Rhineland, emigrating in 1769. Henry worked in Philadelphia with his brother Christian for seven years. He served in the Revolutionary War and then worked in Trenton before coming to Alexandria in 1792. Piercy worked with a succession of partners before leasing the pottery to others in 1799.

Piercy was also a partner in a three-month venture in 1795, selling china and glass from a shop at 406 King Street. In 1974 archaeologists found more than eighty Piercy earthenware vessels in a privy/well at this site. Hundreds more were recovered in 1999 from a waster pile adjacent to the kiln. The wares included plain utilitarian vessels and slip-decorated bowls, pans, and chargers.

Piercy advertised that his wares were “equal to any work in Philadelphia or elsewhere,” which was, in fact, a fair claim.[14] A few characteristics of Alexandria slipware help to distinguish Piercy’s wares from their Philadelphia counterparts, however. Piercy’s pans are all decorated with slip-trailed yellow spiral bands (fig. 17). Piercy’s spirals are consistently even and closely spaced, whereas those from Philadelphia are sometimes wider apart. Piercy’s large dishes are shallow, drape-molded vessels with coggled piecrust rims (fig. 18). They are always decorated with a seven-chamber slip cup, with seven combed straight lines flanked by seven wavy lines. Philadelphia examples are found with different numbers of lines.

Alexandria Mourns George Washington

Alexandria physicians James Craik and Elisha Cullen Dick attended George Washington in his last hours. Upon his death on December 14, 1799, the bells of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House tolled for four days and nights until the former president’s funeral at Mount Vernon, eight miles south of town. The local newspaper printed an article entitled “Washington in Glory—America in Tears”:

On Monday and Wednesday the stores were all closed and all business suspended, as if each family had lost its father. . . every public expression of grief was observed. On Wednesday, the inhabitants of the town, the county, and the adjacent parts of Maryland proceeded to Mount Vernon to perform the last offices to the body of their illustrious neighbor.[15]

While Alexandrians felt a particularly close connection, the entire country mourned Washington’s passing. The Herculaneum Pottery in Liverpool and other manufacturers produced creamware mourning pitchers to honor the great man’s memory. The pitchers depict images of Washington with symbols of mourning such as a memorial obelisk, urns and wreaths, and sometimes the Great Seal of the United States, military ships, maps, or other patriotic symbols. The pitchers bear the phrase “He in Glory, America in Tears,” similar to that printed in the newspaper.

One such mourning pitcher was excavated from a privy behind a wood store and dwelling at 416–418 King Street, Alexandria (figs. 19, 20).[16] It may have been a victim of the fire of 1827 that raged through much of the town.

The Ugliest Pots in Alexandria

Staffordshire potteries exported some really ugly ceramics to America. Some designs were developed to appeal to the American taste; others were probably exported after not finding a market at home. The potteries also exported a large quantity of cheaper seconds and thirds, pieces that did not emerge perfectly from the kiln.

The chamber pot illustrated in figure 21 is one of a matched pair discarded around 1800–1820, along with eight plain creamware chamber pots, in a privy behind the Stabler-Leadbeater Apothecary Shop on South Fairfax Street.[17] Decorated on a lathe with bands of colored slip, they are poorly executed seconds.[18] The bands of slip were unevenly applied and adhered poorly to an overly dry body. The sponge decoration on top of the banding is unusual and unattractive. Although the pots are stamped “wedgwood,” representatives of Josiah Wedgwood & Sons suggest that they were probably made at Ferrybridge by Ralph Wedgwood, a cousin of Josiah.[19] Perhaps the chamber pots were victims of breakage in the retail shop. It was said that due to Ralph’s “partners being dissatisfied at the large amount of breakage caused by his experiments and peculiar mode of firing, the partnership was dissolved.”[20]

Also illustrated is a spill vase (fig. 22), discarded in the 1820s in a privy most likely associated with Gadsby’s Tavern. These contained spills or tapers used to transfer a flame, for instance to light a candle. Also decorated on a lathe with bands of slip, the body is encrusted with bits of broken clay and overpainted with a fish-scale pattern. A fragment of another spill vase was found in neighboring Fairfax County and probably was purchased in Alexandria from the same shipment.

Franklin Maxims Child’s Mug

The “Franklin Maxims” mug found in a privy behind 112–114 South St. Asaph Street is one of just a few pieces of nineteenth-century children’s pottery found in Alexandria (fig. 23). These mugs were made in Leeds as early as 1820 and were produced through the mid-nineteenth century by many potteries in Staffordshire.[21] The source of the proverbs is Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac (first published in 1732).[22]

This particular mug was used and broken in an African-American household, then discarded in the 1850s, according to analysis of the artifacts with which it was found. This property was rented to African-American tenants from 1836 until 1864. Census records show free black and enslaved tenants living there together.[23]

The Reverend James H. Hanson, a white Methodist Episcopal minister, taught black children at the Alexandria Academy from about 1815 to 1847. Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia at that time, but in 1847 the town was retroceded to the Commonwealth of Virginia, where the education of African-Americans was forbidden by law. After the Civil War African-American children could once again be legally educated. The Freedmen Bureau hired an African-American carpenter, George Seaton, to build a school for boys. In 1871 this school and one for girls became public elementary schools for black children. It was nearly another 100 years before Alexandria public schools were fully integrated.[24]

Stoneware and Retrocession

Alexandria’s best-known stoneware potter, Benedict C. Milburn, operated the Wilkes Street Pottery from 1831 until his death in 1867 (figs. 24, 25). Milburn, who worked for china merchants Hugh Smith and his son Hugh Charles Smith, purchased the pottery in 1841. The long-awaited opening of the Alexandria Canal in 1843 aided in its success, as did economic growth in the period after retrocession.

Alexandrians suffered economically from their inclusion in the Federal District (1791–1847), and petitioned for retrocession to Virginia. Congress agreed and a referendum was held. Milburn and Hugh Smith were among the vast majority of Alexandrians who voted in favor of retrocession.[25]

Milburn used three stamps on his stoneware prior to retrocession, each indicating Alexandria’s position as part of the nation’s capitol. These included merchant marks “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA / D.C” and “DUBOIS & REDDICK / ALEXANDRIA D C,” and one of the potter’s marks, “B. C. MILBURN / ALEXANDRIA D. C.”

In 1847 Milburn was no doubt happy to discontinue the use of D.C. in the marks. “H.C.SMITH / ALEXA” was used until Smith’s death in 1850, but most wares were stamped “B.C.MILBURN / ALEXA”; the marks “B. C. MILBURN.” and “B C MILBURN” appear less frequently.

Like many Alexandria businesses, the pottery is likely to have closed during the Civil War. Alexandria was a Union-occupied city, and while two of Milburn’s seven sons signed the Oath of Loyalty (and were later involved in the pottery), three others enlisted in the Confederate Army. In the postwar years, most of the wares were undecorated.

Francine Bromberg, City Archaeologist, Alexandria, provided information on Alexandria’s prehistory used in this section.

James C. Mackay, “A Brief History of Alexandria, Virginia” (Alexandria, Va.: The Lyceum, Alexandria’s History Museum, 1996); and Donald K. Shomette, “Maritime Alexandria: An Evaluation of Submerged Cultural Resource Potentials at Alexandria, Virginia” (1985), pp. 67–69, files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum.

Alexandria Gazette, January 23, 1827.

“Archaeology at Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery,” Alexandria Archaeology Museum, Office of Historic Alexandria, City of Alexandria, Virginia, available online at https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic/archaeology/default.aspx?id=39008 (accessed February 4, 2017).

Robert M. Adams et al., Archaeological Investigation of the Stonegate Development (Including Sites 44AX31, 166 & 167), West Braddock Road, City of Alexandria, Virginia, 2 vols. (Rawlins, Wyo.: International Archaeological Consultants, 1993), 1:48; Mary Ellen N. Hodges, “Appendix J: Native American Ceramics Recovered from Test Units at Site 44AX31,” in ibid., 2:1–3. Francine Bromberg, provided information on Alexandria’s prehistory used in this section.

“Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland: Accokeek” (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum: St. Leonard, Md., 2002, updated 2012), online at ttps://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/PrehistoricCeramics/Prehistoric%20Ware%20Descriptions/Accokeek.htm (accessed February 4, 2017).

The Carlyle House is still standing and open to the public. For information, visit http://www.nvrpa.org/park/carlyle_house_historic_park (accessed February 4, 2017).

Steven J. Shephard, “Reaching for the Channel: Some Documentary and Archaeological Evidence of Extending Alexandria’s Waterfront,” Alexandria Chronicle (Spring 2006).

The ceramics were examined over the years by Merry Abbott Outlaw and other archaeologists working on earlier mid-Atlantic sites.

For French faience (bowls, lidded cooking pots, and plates) found in colonial Illinois, and small handled bowls, pipkins, porringers, and molds found on Canadian sites, see John A. Walthall, “Faience in French Colonial Illinois,” Historical Archaeology 25, no. 1 (1991): 80–105, and Gregory A. Waselkov and John A. Walthall, “Faience Styles in French North America: A Revised Classification,” Historical Archaeology 36, no. 1 (2002): 62–78.

Arell’s Tavern, Site 44AX94, Features MB-B and MB-D, was excavated as part of the Gadsby’s Urban Renewal project in the late 1960s.

The excavation of McKnight’s Tavern, Site 44AX93, Feature GB-2, on the corner of King and Royal Streets, was also part of the urban renewal project in the late 1960s.

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, “A Step Back in Time: Don Carpentier and the Ceramic Workshops at Historic Eastfield Village,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 329–34. The Burslem discovery was the focus of the 2006 Eastfield Village Ceramic Workshop, “British Ceramics: A Newly Discovered Potter’s Tip in Burslem, 1795–1805.”

Virginia Gazette and Alexandria Advertiser, November 1, 1792.

Alexandria Times and District of Columbia Advertiser, December 20, 1799.

Alan Smith, The Illustrated Guide to Liverpool Herculaneum Pottery, 1796–1840 (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), fig. 50. Smith illustrates a similar pitcher from the collection of the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Connecticut. The same engravings were combined with other illustrations on a larger pitcher from the same factory, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (ibid., fig. 49).

This shop was in business from 1796 until 1933, and is now a museum owned and operated by the City of Alexandria.

For a description of how these wares were produced, see Donald Carpentier and Jonathan Rickard, “Slip Decoration in the Age of Industrialization,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 115–34.

Photographs of the marks were examined and identified by Lynn Miller, Information Officer, Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Limited.

Llewellynn Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain, new ed., rev. (London: J. S. Virtue & Co., 1883), p. 278.

Morton Yarmon, Early American Antique Furniture (Greenwich, Conn.: Fawcett Books, 1952).

Benjamin Franklin, “The Way to Wealth,” Poor Richard’s Almanac (1758; reprint, Carlisle, Mass.: Applewood Books, 1986). See also Jared Sparks, ed., The Works of Benjamin Franklin, 10 vols. (Boston: Hillard Gray, 1836–40), 2:92–103, available online at http://www.swarthmore.edu/SocSci/bdorsey1/41docs/52-fra.html (accessed February 4, 2017).

Phillip Terrie, “Alexandria’s Main Street Residents: A Social History of the 500 Block of King Street,” unpublished ms. in the files of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum, Alexandria, Va., 1979.

“History of Alexandria’s African American Community,” Alexandria Black History Museum, at https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic/blackhistory/default.aspx?id=37214 (page updated on January 9, 2016; accessed February 4, 2017).

Mark David Richards, “The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004,” Washington History (Spring–Summer 2004): 54–82. The Virginia General Assembly accepted Alexandria back into the Commonwealth on March 13, 1847.