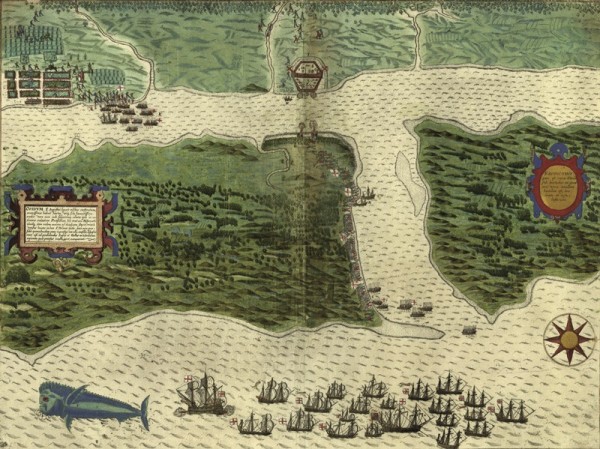

Baptiste Boazio, S. Augustini: pars est terra Florida, sub latitudine 30 grad, ora vero maritima humilior eset, lancinata et insulosa, 1589. (Hans and Hanni Kraus Sir Francis Drake Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.) Baptiste Boazio accompanied Francis Drake on his raid and burning of St. Augustine, May 28–30, 1586.

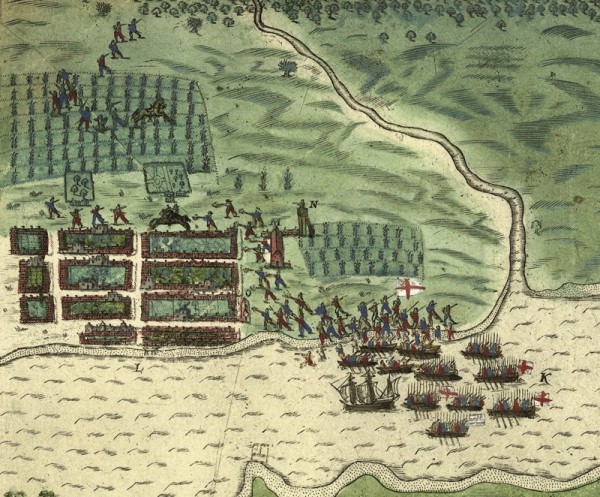

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 1 showing the nine-block sixteenth-century area that is preserved today in the streetscape of the south part of St. Augustine.

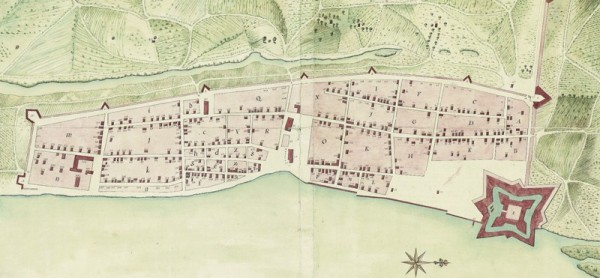

Elixio de la Puente, Plano de la Real Fuerza, Baluarte y Linea de la Plaza de St. Augustín de la Florida, 1764. (The University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries, 975.918129993603445 [OCLC].) When Elixio de la Puente became the property agent for the departing Spanish landowners in 1763, he made this map, which identifies the owners and characteristics St. Augustine’s Spanish-owned properties at the end of the First Spanish Period. The street plan of the eighteenth-century walled city has remained in this configuration to the present day.

City of St. Augustine excavations are required to mitigate all building-related, ground-disturbing construction within the colonial city. Here, excavations on Aviles Street are underway ahead of an underground utility installation. (Photo, Ted Morris.)

Barrel wells were used in St. Augustine from 1565 until the late eighteenth century, and most of the nearly intact ceramic vessels have been found in wells. This late-sixteenth-century well is being excavated at the site of the Convento de San Francisco, 8SA-24. (Courtesy, Florida Museum of Natural History.)

Middle-Style olive jar, probably Andalucia, Spain, ca. 1566. Unglazed earthenware. H. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH 8SJ31-2006-3137; photo, Jeff Gage.) This jar had been deposited in a 1565–1566 well in St. Augustine.

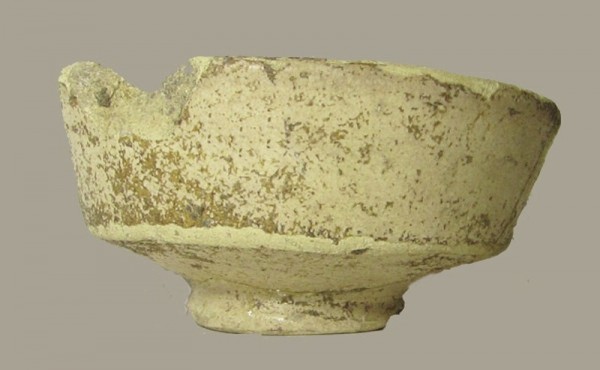

Columbia Plain escudilla (carinate bowl), Andalucia, Spain, ca. 1566. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 4 3/4". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC #1998-0386; photo, Jeff Gage.) This majolica piece was deposited in a ca. 1580 household trash deposit in St. Augustine, is an example of Columbia Plain Gunmetal.

Isabela Polychrome majolica plate fragment, Andalucia, Spain, 1490–1580. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 6 1/8". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection BDAC # 1998-0386.) This plate had been deposited in the refuse area of a ca. 1585 Spanish household in St. Augustine.

Bacín (chamber pot), probably Spain, 1450–1750. Unglazed earthenware H. 9 13/16". (Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH SA26-1-422; photo, Jeff Gage.) This chamber pot had been deposited in a ca. 1600 well in St. Augustine.

San Luis Polychrome majolica plates, Mexico City, Mexico, ca. 1650–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. of upper right plate 10 15/16". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC # 1995-0751-F7.) These examples were recovered from a ca. 1700 St. Augustine trash pit.

Guadalajara Polychrome vessel, Guadalajara, Mexico, 1650–1800. Painted and burnished earthenware. H. 3 3/8". (Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH SA34-2-85; photo, James Quine.) This vessel had been deposited in a ca. 1700 St. Augustine Spanish household trash pit.

Abó Polychrome majolica plate, Puebla, Mexico, 1650–1700. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 1/16". (Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH SA30-3-214; photo, Jeff Gage.) This plate was deposited in the trash pit of a St. Augustine Spanish household between 1680 and 1700.

Puebla Blue on White pocillo (chocolate cup), Puebla, Mexico, 1650–1720. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/8". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC # 2005-0503-F1.) This example had been deposited in the trash pit of a Spanish household in St. Augustine between 1700 and 1720.

Colonoware bowls, St. Augustine, late seventeenth century. Low-fired, earthenware. D. of larger bowl 12 13/16". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC# 2016-B6L3-F10.) These bowls were found together in a ca. 1700 Spanish household trash pit.

Colonoware jar, St. Augustine, Florida, early eighteenth century. Low-fired, shell-tempered earthenware. H. 15 3/8". (Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH SA7-4-223; photo, Jeff Gage.) This jar had been deposited in a ca. 1730 Spanish household well.

Jar or bowl fragment, San Marcos Stamped (Guale Indian tradition), St. Augustine, Florida, late seventeenth century. Low-fired earthenware. (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC # 1992-0737-F24A.) This fragment has paddle-stamped decoration on the exterior surface and is inscribed “. . . onzalo” in the interior. It was deposited in a ca. 1680–1690 Spanish household well.

Polychrome enameled bowl, Staffordshire, England, 1740–1760. White salt-glazed stoneware. D. 4 5/16". (City of St. Augustine Archaeological Program Collection, BDAC # 2004-2000.) This bowl was found in the trash pit of a ca. 1750 St. Augustine household.

Serving dish, probably Staffordshire, England, 1762–1780. Creamware. L. 12". (Florida Museum of Natural History, FLMNH SA34-3-306/24; photo, Jeff Gage.) This fluted and molded dish, which has a feather-edge rim pattern, was recovered from a ca. 1770 St. Augustine refuse pit.

St. Augustine, Florida, is the oldest extant European settlement in North America. It was founded in 1565, seventy-three years after Columbus sailed to America and forty-two years before Jamestown, and has been occupied ever since.[1]

The site was not selected for its natural resources, but rather because it was the closest good harbor to the French outpost of Fort Caroline, which had been established (illegally, in Spanish eyes) a year earlier at what is today Jacksonville, Florida. However, St. Augustine’s location was also suitable for patrolling and defending the critical east coast of Florida, the principal homeward-bound route for the Spanish treasure fleets, which by then were under continuous threat from pirates, hurricanes, and shipwrecks.

St. Augustine was the capital of the territory delineated by the Spaniards as “La Florida,” which encompassed an area that initially extended east to the Mississippi and north to Virginia. Spanish activities throughout La Florida were organized and administered from St. Augustine, including the extensive Franciscan mission systems, military outposts, alliances with native polities, and cattle ranching.[2] The city also served as the conduit for La Florida’s connections to the larger Spanish-American and European worlds.

The colony was not profitable for Spain, since the land was not suitable for agriculture and there were no mineral resources. Nevertheless, St. Augustine’s strategic position in guarding the shipping lanes—and later as Spain’s northern buffer against English incursions in America—convinced the Spanish Crown to provide the colony an annual subsidy (situado) of money and goods from Mexico. That became the principal source of goods and income in St. Augustine until the mid-eighteenth century.

In 1572 the town had a population of about 300 people, nearly all of them soldiers and their dependents, and was formally organized on an urban grid plan (figs. 1, 2). Within a few generations, the majority of St. Augustine’s inhabitants were Africans, criollos (people of Spanish descent but born in America), Native Americans, or of multiracial parentage. Many Spanish soldiers married Native American women, a practice that was already well-established throughout the Spanish colonies in Mexico and the Caribbean. This tradition strongly influenced the nature of everyday life in Spanish St. Augustine, introducing a distinctive Native American influence into the households of virtually all of the town’s inhabitants.[3]

The attack on the settlement by pirate Robert Searles in 1668, and the establishment of Charleston just to the north in the English colony of South Carolina in 1670, inspired the Spanish Crown to invest seriously in St. Augustine’s defenses. Military encounters between Spanish and English forces began almost as soon as Charleston was established and escalated dramatically through the eighteenth century. Construction of a stone fort, Castillo de San Marcos, began in 1672 and was completed in 1695, and over those years the garrison was significantly enlarged. In 1702 St. Augustine was attacked and burned by troops sent by Carolina Governor James Moore. Subsequent strengthening of the garrison and an influx of immigrants and Native American refugees to St. Augustine dramatically increased both the physical size and the population of the town, making it more diverse.

Under its mercantilist colonial economy, Spain forbade trade between foreigners and the Spanish colonies, which until the end of the seventeenth century restricted the town’s material life to Spanish-tradition or local goods. Once English settlements were established in Carolina and Georgia, however, St. Augustine residents enthusiastically took advantage of the opportunities for contraband trade. Goods from English, French, and Dutch ships were increasingly available in the town in the early eighteenth century either through illicit trade or from cargoes of prizes taken by Spanish privateers.[4]

Spanish economic expansion in St. Augustine ended abruptly in 1763, when Florida was traded to England in exchange for Cuba at the end of the Seven Years’ War. Nearly the entire population—3,104 African, Christian Native Americans, and Spaniards—left St. Augustine and went to Cuba rather than live under Protestant British rule (fig. 3).

St. Augustine was a British colony from 1763 until 1784, becoming a stronghold for British Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution.[5] A large group of Minorcan farmers and fishermen also arrived after 1777, refugees from a failed agricultural colony that had been organized in 1768 by Alexander Turnbull at New Smyrna in Florida. Several hundred Native Americans of Creek origin, who by then were called Seminoles, also came to St. Augustine, and many of them settled in the abandoned mission villages around the city.

Florida was returned to Spain in 1784. During the ensuing thirty-seven-year period of Spanish colonial rule (known as the Second Spanish Period), St. Augustine became an international settlement, closely connected to the new United States and a much wider Atlantic world. It was a period of economic and social internationalization, with a far-flung network of trade relations. St. Augustine’s colonial period ended in 1821, when Florida became a territory of the United States. Today it is a town of some 16,000 residents, with an economy based on tourism generated by its ancient status and historic remains.

Historical archaeology has been underway in St. Augustine’s colonial sites since the 1930s, resulting in two major collections from which the selections in this essay were drawn. The Florida Museum of Natural History, located on the campus of the University of Florida in Gainesville, curates collections from projects conducted by the university and the state since the 1960s.[6] The City of St. Augustine’s own collection includes materials from sites excavated as part of the St. Augustine City Archaeology program, which was established in 1985 (figs. 4, 5).[7]

St. Augustine’s longevity and its archaeological ceramic assemblage are unique among the town sites of North America. These objects reflect the poverty of the community through much of its history, as well as the fact that the town has been occupied for 450 years. To us as archaeologists, the most singular aspect of St. Augustine’s long colonial history is the first Spanish occupation (1565–1763), so we have chosen to emphasize that period in choosing our “top ten” ceramic pieces. Some are not beautiful and very few are intact, but all evoke important aspects of St. Augustine’s colonial past.

Spanish Olive Jar

A nearly intact, unglazed earthenware storage jar was found at the bottom of a barrel well at the site of the initial settlement of St. Augustine in 1565 (8SJ31; the Fountain of Youth Park site). It is one of the first Spanish ceramic vessels to have reached St. Augustine (fig. 6).[8] These jars, known as olive jars (tinajas or peruleras) were the primary shipping containers throughout the Spanish Americas, and they are the most abundant ceramics on most Spanish colonial sites throughout the region. Olive jars vary widely in shape and size, depending on their contents and on their period of production. The earliest ones were spherical and amphora-like, with loop handles and a narrow everted neck and rim. After about 1550 they lost their handles and became elongated, with applied doughnut-shaped rims.[9]

Morisco Majolica

Spanish majolica is a tin-enameled earthenware that is technologically equivalent to Dutch and English delft, French faience, and Italian maiolica. It was a ubiquitous symbol of Spanish identity in St. Augustine, and it is one of the few artifact categories strongly associated with elite St. Augustine households. During most of the sixteenth century, colonists’ tableware ceramics were primarily those of the Iberian Morisco (late medieval) tradition, Moorish-influenced pottery produced in and imported from Christian Spain and Portugal.[10]

The Columbia Plain escudilla illustrated in figure 7 is a typical Morisco individual-use vessel. This plain, cream-colored, tin-enameled ware is the most frequently occurring majolica on most sixteenth-century Spanish colonial sites. This example was found in St. Augustine in a household trash deposit of 1580–1600. Although production and use of Columbia Plain pottery continued well into the seventeenth century, in St. Augustine Mexican-produced majolica gradually began to replace Spanish majolica after about 1580.

A plate fragment of another Morisco majolica ware, known as Isabela Polychrome, is illustrated in figure 8. Isabela Polychrome is rare on American sites after about 1550, and pieces with intact rims are often decorated with the last remnants of medieval Arabic calligraphy in Spanish decorative arts. This particular plate, which was excavated at the site of a 1580–1590 household, was probably an heirloom.

Earthenware Bacín (Chamber Pot)

Spaniards in St. Augustine apparently did not dig latrines or privies or outhouses (not one has been found archaeologically), but instead met their sanitary needs with bacínes, or chamber pots.[11] Bacínes were frequently lead-glazed or tin-enameled. An unglazed earthenware example (fig. 9) shows the typical shape of a sixteenth-century Spanish bacín, which was of medieval Moorish origin and would have had a wide everted rim. This shape persisted in Spain and the Spanish Americas until the end of the eighteenth century, when it was largely replaced by the round-bodied, squat English form.

Mexico City Majolica

Majolica production began in Mexico City during the third quarter of the sixteenth century, introduced by potters from Seville.[12] At about the same time, in 1571, the Spanish king mandated the Mexico City treasury to supply the government subsidy that supported St. Augustine’s garrison. St. Augustine’s purchasing agents went to Mexico City annually to collect the subsidy in goods and specie, and, not surprisingly, majolica found in St. Augustine from about 1580 until 1700 is predominantly from Mexico City.

Mexico City majolicas are among the first expressions of emergent criollo expression in the Americas. The potters abandoned the earlier Morisco forms, and instead adopted heavy-bodied versions of the newer Italian Renaissance–inspired forms. The palette is blue or green and cream with occasional black-line detail, and motifs are distinctive from those found on either Italian or Sevillian contemporary tin-enameled wares. The nearly complete San Luis Polychrome plates illustrated in figure 10 were recovered together from a discrete household-trash deposit of circa 1675, suggesting the possibility of matched sets of seventeenth-century tableware ceramics as well as a major breakage episode.

Guadalajara Polychrome Earthenware

In a syncretic melding of both technology and meaning, Guadalajara Polychrome pottery combines European forms and wheel-thrown production techniques with Aztec decorative and paste characteristics (fig. 11).[13] The clay of these vessels, known as búcaro, was fragrant when wet, and Spanish women believed that water kept in it was both refreshing and good for the complexion. This also led to the habit of bucarofágia, or eating búcaros.[14] During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, not only Guadalajara vessels, but also broken Guadalajara potsherds were exported by the thousands from Mexico to Spain and other Spanish-American colonies.[15]

Puebla Majolica

A majolica industry began in Puebla, Mexico, during the late sixteenth century, and by the mid-seventeenth century at least seventeen pottery workshops were active.[16] In 1702 the responsibility for the St. Augustine subsidy was switched from Mexico City to Puebla’s treasury, and after that time most of the majolica tableware in the community came from Puebla. Puebla potters produced vessels influenced by Chinese porcelain and by the products of Talavera de Reina in Spain, with a cream-colored paste, glossy off-white background enamel, and vibrant decoration in polychrome and blue on white.

The colorful plate illustrated in figure 12 is a late-seventeenth- or early-eighteenth-century example of the lively naturalistic polychrome decoration of Abó Polychrome. The small cup shown in figure 13, though not as colorful, illustrates the multicultural convergences of Spanish America. Although tin-enameled in the tradition of Spain, it adopts the Chinese cup form for tea drinking but was used by Spaniards to drink chocolate, a Mexican introduction.

Colonowares

The term colonoware as used by archaeologists in St. Augustine is a category of pottery that integrates elements from multiple ceramic traditions, generated by engagements among people with recognizably distinct traditions in a colonial setting. There were never large communities of African slaves in Spanish St. Augustine, and most of the colonoware found archaeologically combines European forms with traditional Native American paste, decoration, and technology. Cooks in Spanish St. Augustine, however, apparently preferred unmodified Native American vessels, and assemblages of colonoware forms are relatively infrequent.

The vessels illustrated in figure 14 were recovered from the same refuse pit, along with unmodified Native American pottery and some Spanish ceramics dating to the very early eighteenth century. Both are hand built and low fired. The small ring-footed bowl is shell tempered, and the rimmed bowl is sand tempered, burnished with a distinctive red surface.

The jar shown in figure 15 might be one of the only recognizably African-influenced vessels found in St. Augustine. The vessel is hand built with shell-tempered paste, unlike that of local Native American vessels. In its form and finish the low-shouldered globular body is similar to some West African pots, but the applied ring rim is reminiscent of Spanish olive jars (see fig. 6).[17] It was found in a circa 1730 well at the homesite of cavalry soldier Gerónimo de Hita y Salazar, who lived in St. Augustine but supervised military training at the free African settlement at Fort Mose.[18]

Guale Pottery

Native American–made pottery is the most frequently found ceramic artifact in St. Augustine’s Spanish-period households. It was the principal cooking ware in the town’s kitchens, from that of the governor to those of militia privates. Ceramics produced by Timucua, Guale, and Yamassee potters were used as well but by the end of the seventeenth century Guale San Marcos pottery dominated.[19] The vessels overwhelmingly occur in traditional Native American forms, with little effort to accommodate Spanish tastes. They were a market commodity, and are listed as assets in Spanish probates.[20] A fragment of San Marcos Stamped pottery found in a late-seventeenth-century Spanish-household trash pit is remarkable for the partial signature inscribed on its interior—“. . . onzalo” (fig. 16). Whether it refers to the maker or an intended owner, the signature suggests that the Guale potter was literate. This is the only known example of a signed, colonial-period Native American vessel in Florida, and perhaps beyond.

English Ceramics

During the early decades of the eighteenth century St. Augustine’s situado supplies of goods and money was extremely erratic, sometimes not arriving for years. And even when situado was sent, it didn’t always arrive if supply ships were sunk by hurricanes and storms or captured by privateers.[21]

St. Augustine’s residents gradually began to take matters into their own hands. Entrepreneurial individuals set up their own shops selling whatever goods they could acquire, whether legal or illegal. Trade with the English—illegal until after 1750—flourished, and one observer in 1736 claimed that he saw six English merchant vessels moored at the same time in the St. Augustine harbor.[22] A Staffordshire enamel-painted white salt-glazed stoneware punch bowl (fig. 17) was found in a Spanish context of the mid-eighteenth century, near the peak period of Spanish-English enmity.

Creamware

In 1762, the year before Spain ceded Florida to England, the English pottery maker Josiah Wedgwood patented cream-colored earthenware. Because of its known date of introduction and subsequent rapid popularity, English creamware provides one of the best archaeological markers for the British period (1763–1784) in St. Augustine.[23] Even after Spain regained Florida in 1784 and many of the former Spanish residents returned, creamware remained the dominant tableware, eclipsing the role majolica formerly held. A molded creamware serving dish (fig. 18) was excavated at the home/shop of a well-to-do Second Spanish Period (1784–1821) merchant. It was in a trash pit that also contained more than thirty broken creamware vessels, probably part of a damaged commercial shipment. The contents of the pit reflect the abundance of creamware in St. Augustine during the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

For an authoritative treatment of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and his expedition to Florida, see Eugene Lyon, The Enterprise of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1976). The site of the 1565 encampment is thought to be on the grounds of the present-day Fountain of Youth Park in St. Augustine, about one kilometer north of the Castillo de San Marcos. Kathleen Deagan, Historical Archaeology at the Fountain of Youth Park (8SJ31), St. Augustine Florida (1934–2007), Florida Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publications in Archaeology 59 (2008), www.flmnh.ufl.edu/histarch/FOY_Site_Reports/2008_Deagan_FOY_FieldReport.pdf (accessed September 1, 2016).

Amy Bushnell, The King’s Coffer: Proprietors of the Spanish Florida Treasury, 1565–1702 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1981). See also Amy Bushnell, Situado and Sabana: Spain’s Support System for the Presidio and Mission Provinces of Florida, American Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Papers 74 (New York, 1995).

Summaries of archaeological work documenting this include Kathleen Deagan, Spanish St. Augustine: The Archaeology of a Colonial Creole Community (New York: Academic Press, 1983); Kathleen Deagan, “The Archaeology of Sixteenth-Century St. Augustine,” The Florida Anthropologist 38, nos. 1–2 (1985): 1–89; Kathleen Hoffman, “The Development of a Cultural Identity in Colonial America: The Spanish-American Experience in La Florida,” Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, Gainesville, 1994.

For eighteenth-century St. Augustine, see John Tepaske, The Governorship of Spanish Florida, 1700–1763 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1964); Susan R. Parker, “The Second Century of Settlement in Spanish St. Augustine, 1670–1763,” Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, Gainesville, 1999.

On the British period in St. Augustine, see Daniel L. Schafer, St. Augustine’s British Years, 1763–1784, El Escribano 38 (St. Augustine, Fla.: St. Augustine Historical Society, 2002), and Robin Fable and Daniel Schafer, “British Rule in the Floridas,” in The History of Florida, edited by Micheal Gannon (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013), pp. 144–61. On Minorcans, see Patricia Griffin, Mullet on the Beach: The Minorcans of Florida, 1768–1788 (St. Augustine, Fla.: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1990).

See its website, www.flmnh.ufl.edu/histarch (accessed August 29, 2016).

See its website, www.digstaug.org (accessed August 29, 2016); Carl Halbirt, “The City of St. Augustine’s Archaeology Program,” The Florida Anthropologist 46, no. 2 (1993): 101–4 (1993).

Deagan, Historical Archaeology at the Fountain of Youth Park (8SJ31).

Basic references for olive jars include John Goggin, The Spanish Olive Jar: An Introductory Study, Yale University Publication in Anthropology 62 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1960); Kathleen Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean, 1500–1800, Volume I: Ceramics, Glassware, and Beads, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002), pp. 30–35; Mitchell Marken, Pottery from Spanish Shipwrecks (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994); George Avery, “Pots as Packaging: The Spanish Olive Jar and Andalusian Transatlantic Commercial Activity, 16th–18th Centuries,” Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, Gainesville, 1997.

John Goggin, Spanish Majolica in the New World, Yale University Publications in Anthropology 72 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1968), pp. 207–8; Florence Lister and Robert Lister, Andalucian Ceramics in Spain and New Spain (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987), pp. 93–130; Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies, pp. 53–61.

Florence Lister and Robert Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica Pottery in the Valley of Mexico, Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 39 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1982).

Goggin, Spanish Majolica; Lister and Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica Pottery; Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies, pp. 71–77.

Thomas H. Charlton and Roberta Katz, “Tonala Bruñida Ware, Past and Present,” Archaeology 32 (1979): 45–53; Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies, pp. 44–46.

Maria Concepción García Saíz, “Mexican Ceramics in Spain,” in Cerámica y Cultura: The Story of Spanish and Mexican Mayólica, edited by Robin F. Gavin, Donna Pierce, and Alfonso Pleguezuelo (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), pp. 186–203.

Ibid.

Lister and Lister, Sixteenth Century Maiolica Pottery, pp. 230–52; Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies, pp. 77–87.

See, e.g., Christopher DeCorse, “Oceans Apart: Africanist Perspectives on Diaspora Archaeology,” in Digging the Afro-American Past, edited by T. Singleton (Richmond: University of Virginia Press, 1999), p. 153.

Fort Mose was established in 1738 as a community for enslaved Africans who escaped to Florida from plantations in South Carolina. Spain decreed that any who reached St. Augustine would be given sanctuary and a place in the militia. For more information, see Kathleen Deagan and Jane Landers, “Fort Mose: The Earliest Free African-American Community in the United States,” in Digging the Afro-American Past, edited by T. Singleton (Richmond: University of Virginia Press, 1999), pp. 261–82; and Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon, Ft. Mose: Colonial America’s Black Fortress of Freedom (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995).

On Native American ceramics in St. Augustine, see Bruce Piatek, “Non-Local Aboriginal Ceramics from Early Historic Contexts in St. Augustine,” The Florida Anthropologist 38 (1985): 81–89; Kathleen Deagan, “St. Augustine and the Spanish Mission Frontier,” in Spanish Missions of La Florida, edited by B. G. McEwan (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1993), pp. 87–110; Gifford Waters, “Aboriginal Ceramics at Three 18th Century Mission Sites in St. Augustine, Florida,” in From Santa Elena to St. Augustine: Indigenous Ceramic Variability (a.d. 1400–1700), edited by Kathleen A. Deagan and David H. Thomas, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 90 (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 2009), pp. 165–76. On San Marcos pottery, see John Otto and Russell Lewis, A Formal and Functional Analysis of San Marcos Pottery from Site SA-16-23, St. Augustine, Bureau of Historic Sites and Properties Bulletin 4 (Tallahassee: Florida Department of State, 1975), pp. 95–117; Rebecca Saunders, Stability and Change in Guale Indian Pottery, a.d. 1300–1702 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000); John Worth, “Ethnicity and Ceramics on the Southeastern Atlantic Coast: An Ethnohistorical Analysis,” in From Santa Elena to St. Augustine, pp. 179–209.

John Hann, trans., “Inventory and Auction of the Estate of Don Francisco de la Rua, deceased in 1649 in St. Augustine, Florida,” in Spanish St. Augustine: A Sourcebook for America’s Ancient City, edited by Kathleen Deagan (New York: Garland Press, 1991), pp. 492–540.

Joyce Harman, Trade and Privateering in Spanish Florida, 1762–1763 (St. Augustine, Fla.: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1969); Carl Halbirt, “La Ciudad de San Agustín: A European Fighting Presidio in Eighteenth-Century La Florida,” Historical Archaeology 38, no. 3 (2004): 33–46; Kathleen Deagan, “Eliciting Contraband through Archaeology: Illicit Trade in Eighteenth-Century St. Augustine,” Historical Archaeology 41, no. 4 (2007): 98–116.

John Tepaske, The Governorship of Spanish Florida, 1700–1763 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1974), pp. 88–89.

Information on the development and evolution of creamware and pearlware can be found in George Miller and Robert Hunter, “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 135–61.