Attributed to Jacques Cortelyou, Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt (the Castello plan), ca. 1660. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections. nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c0b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed May 20, 2017.) This is a photograph of the manuscript map in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana in Florence, Italy. It is the earliest known plan of New Amsterdam, and the only one dating from the Dutch period.

Detail, Totius Neobelgii Nova et accuratissima tabula (the Restitutio-Carolus Allard map), 1674. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections. nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c40-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.) In 1673 the Dutch reclaimed New York from the English but returned it permanently the following year as part of the treaty that ended the Third Anglo-Dutch War. The canal shown is the Herren Gracht, which is today’s Broad Street.

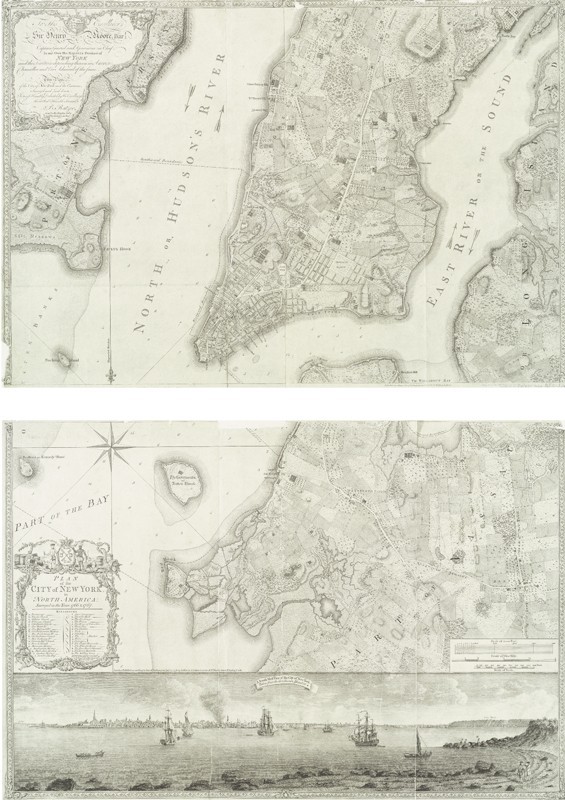

Bernard Ratzer, Plan of the City of New York, in North America, surveyed in the years 1766 and 1767, 1776. The vignette at the bottom is a southwest view of the city, taken from Governors Island in New York Harbor. (Courtesy, New York Public Library.)

Archaeological excavations at the Stadt Huys Block site, 1979. (Photo, courtesy of Nan A. Rothschild.)

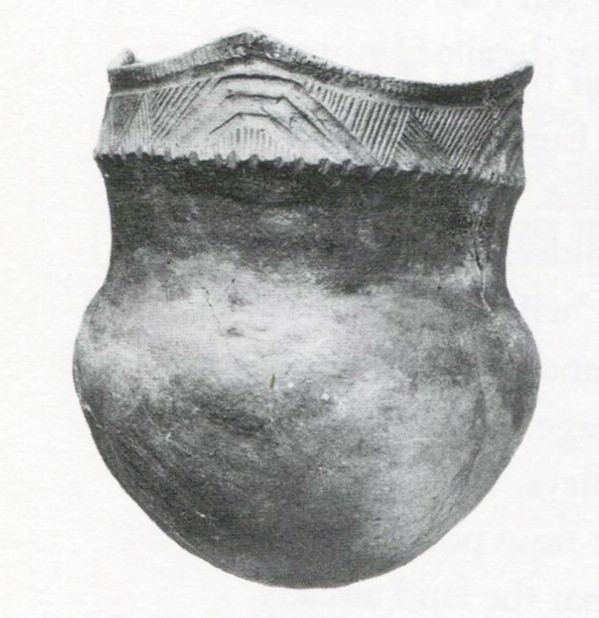

Pot, Late Woodland period, A.D. 900–1600. Low-fired earthenware. H. 13". (Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, negative no. 5551.)

William L. Calver, New York City avocational archaeologist, excavating this or a very similar pot at 214th Street and Tenth Ave., 1906. (Photo, Department of Library Sciences, American Museum of Natural History, negative no. 24449.)

Jan Jansz. Buesem (Dutch, ca. 1600–ca. 1649), Peasant Meal, 1625–1650. Oil on panel, 8 1/16 x 11 7/16". (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-2555.) A red earthenware pan and porringer sit on the table. On the floor, from left to right, are a small, red earthenware pot with a spout, a small brazier with a square-shaped rim, a pitcher, a large cook pot, and a pitcher with a broken rim.

Cooking pots, Netherlands and possibly New York, ca. 1650–1690. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of red vessel 4 1/2"; D. 4"; D. of buff vessel 12". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.)

Nieu Amsterdam, ca. 1643–1650. (The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c02-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.) The Dutch man on the right is holding tobacco leaves in his left hand. Slaves carry goods in trays balanced on their heads.

Contents of the barrel discovered at the Broad Financial site in Lower Manhattan. This group of artifacts has been tentatively identified as a spirit cache created by an African in the mid-seventeeenth century. (Courtesy, New York State Museum; photo, Josh Nefsky.)

Dish, attributed to Gerrit Willemsz Verstraeten (Dutch, b. ca. 1615), ca. 1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, New York State Museum; photo, Josh Nefsky.)

Jan Havicksz. Steen (Dutch, ca. 1625–1679), Tavern Scene, ca. 1661–1665. Oil on canvas, 17 7/16 x 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, on loan © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, CTB.1957.3.) Stoneware jugs, such as the one seen on the table here, were likely the models for the tavern jugs made by a New York potter using local earthenware clays. The man shown with a pipe has cut tobacco from the roll on the table and is lighting it in a red earthenware brazier that holds smoldering peat. Smoking was a popular activity in New York taverns, based on the number of white clay pipe fragments found in the excavation of King’s House Tavern.

Jugs, New York, New York, ca. 1670–1706. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 8" and 7 3/4". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.)

Barber’s bowl and basin, Crolius or Remmey potteries, New York, New York, ca. 1730–1775. Salt-glazed stoneware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) The painted motifs are symbols of the barber’s trade: a straight razor, a scissors, and what might be a brush or powder puff.

Philip Dawe and Robert Sayer, The Patriotick barber of New York, or the Captain in the suds, 1775. Mezzotint. Plate 13 3/4 x 9 3/4". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1946-100.) The incident portrayed is said to have occurred when a barber on Barclay Street refused to finish shaving a customer after the latter was revealed—by the delivery of a letter addressed to “Capn Crozer”—as a British officer. The half-shaven and suds-covered officer was summarily pushed out the door as onlookers laughed. One of the engravings on the wall is of William Pitt (see fig. 16), and wig boxes labeled with the names of local patriots, including Isaac Sears and Jacobus van Zent (Zandt), are piled against the wall and on the floor. The broken bowl on the floor to which the barber is pointing is the same shape as the stoneware one illustrated in fig. 14 but was probably made of refined earthenware.

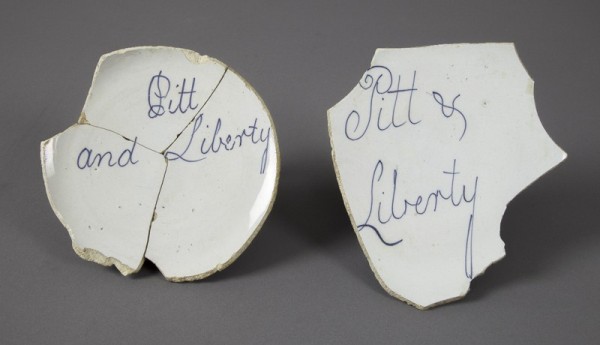

Punch bowl fragments, probably Liverpool, England, ca. 1750–1775. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, New York State Museum; A2005.29C.999.11-12; photo, Donghyun Kim.) These bowls and three others with the same patriotic motto have no wear marks and were probably damaged in transit. William Pitt, an influential member of the British government in the 1750s and 1760s, was popular with American colonists because he opposed the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties.

Teapot, England, ca. 1765–1783. Creamware. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) This enamel-decorated “chintz-style” vessel was likely a personal possession of a British officer. Vessels with this sort of decoration have been attributed to either the Leeds or Greatbatch potteries, decorated by David Rhodes or in his style.

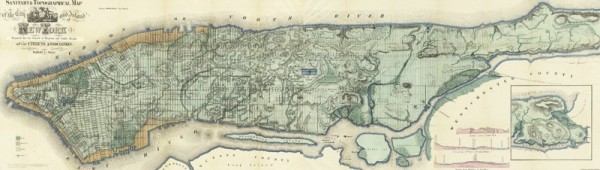

Egbert Viele, Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York (the Viele map), 1865. (Courtesy, David Rumsey Map Collection.) This map shows the extent of landfill along the shores of Manhattan Island prior to that year.

Small bowl, possibly Wood and Caldwell, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1801–1809. Pearlware. D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) A number of objects in this pattern were part of a shipment that likely was damaged in transit and dumped into the fill of Whitehall Slip.

Teabowl and saucer, China, ca. 1785–1810. Porcelain. D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, New York State Museum, A2005.29A.1544.83, 84; photo, Donghyun Kim.) Two teacups and three saucers with the enameled motif of two lovebirds on a bar were found in a deposit probably associated with the Bowne family, whose residence and druggist shop was on Hanover Square during the early nineteenth century. Teawares with this lovebird motif were often given as marriage gifts, according to David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1984), pp. 95–96.

Teapot, Thomas, John, and Joseph Mayer, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1842–1855. Whiteware, printed “Florentine” pattern. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, New York City Archaeological Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission; photo, Donghyun Kim and Jeanette Miller.) Printed motifs purportedly showing images of faraway European or Asian scenes evoked the romance of foreign locales for both English and American consumers.

Teacup and saucer, Spode, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1810–1833. Whiteware, printed “Geranium” pattern. H. of teacup 2 1/4", D. of saucer 5 1/2". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.2, 3; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

Plate, unknown maker, probably England, ca. 1830–1850. Whiteware, printed “Willow” pattern. D. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.4; photo, Donghyun Kim.) All were found in a ca. 1840–1850 deposit.

Plate, Thomas, John, and Joseph Mayer, Burslem, Staffordshire, England, 1842–1855 (possibly 1846–1855). White granite. D. 8". Marked “T.J. & J. Mayer’s Berlin Ironstone.” (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.999.30; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

Teacup and saucer, probably French, ca. 1840–1860. Hard-paste porcelain with painted gilded motif. H. of teacup 3 1/4". (Courtesy, the New York State Museum, A2005.29G.331.2, A2005.29G.348.2; photo, Donghyun Kim.)

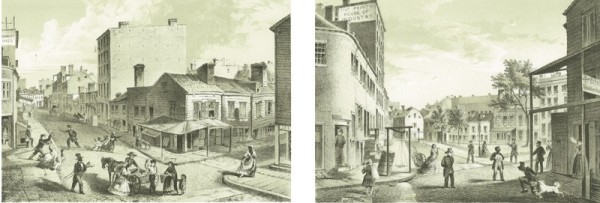

The Five Points in 1859: Crossing of Baxter (late Orange) Park (late Cross) and Worth (late Anthony) Sts.; The Five Points in 1859: View Taken from the Corner of Worth and Little Water St., 1860. (Photo, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library; New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-26ef-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99, accessed February 5, 2017.)

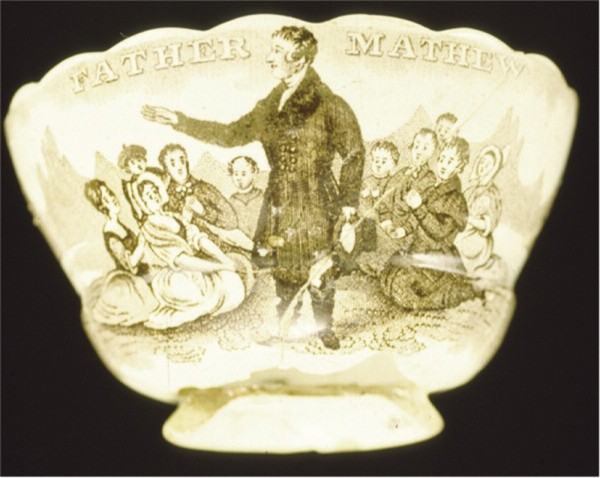

Teabowl, William Adams and Sons, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, ca. 1838–1861. Whiteware, printed “Father Mathew” pattern. H. 3 1/4". (Courtesy, Museum of the City of New York.) This image, printed in other colors in addition to brown, depicts Father Theobald Mathew, an Irish priest who became president of the Cork Total Abstinence Society in 1838, preaching to his flock about the virtues of temperance. He came to America on speaking tours in 1849 and 1851, and addressed at least one large crowd at City Hall near the Five Points.

By the time of Dutch colonization in the 1620s, the land that became New York City had been occupied by Native Americans for 13,000 years. Located where land and water met, the area was rich in resources, especially migratory birds, fish, and shellfish. The region’s appeal for the Dutch was the fur trade with the Native Americans up the Hudson River near today’s Albany. They established New Amsterdam at the river’s mouth because of its natural port for transferring goods to oceangoing vessels and its strategic location for protecting the river from European competitors.

For the first few decades of the colony’s existence, New Amsterdam was a company town administered by the Dutch West India Company (dwic) and populated, for the most part, by its male employees (fig. 1).[1] But in the 1640s, after the removal of the DWIC monopoly on the fur trade and a lull in conflict with the Native Americans, more families settled there. European settlers came from many different countries, especially those around the Netherlands.[2] Africans were also part of the city from its founding when the first slaves were brought to New Amsterdam in the 1620s. New Amsterdam had become a settler colony and a slave society by 1664, when the English conquered it and renamed it New York.[3]

After the English conquest, New York continued in its role of entrepôt (fig. 2). As the fur trade waned, it was replaced with trade in locally produced agricultural goods, most of which went to the Caribbean islands to provision the slaves on the plantations there. The city grew as the West Indian trade and its supporting crafts and businesses, including retailers who sold imported English finished goods such as ceramics, became the backbone of its economy. “New York . . . lived by feeding the slaves who made the sugar that fed the [English] workers who made the clothes and other finished wares that New Yorkers didn’t make for themselves.”[4] Its demographics changed with an influx of immigrants from England, Scotland, and France, especially Huguenots after 1685, and, after about 1710, Germany. Nevertheless, the labor force increasingly was made up of enslaved Africans.[5]

On the eve of the American Revolution, many New Yorkers were economically dependent on international trade and loyal to the crown. The city suffered during the Revolutionary War; under British occupation from 1776 to 1783 there were several ruinous fires that destroyed much of New York’s infrastructure and trade was severely curtailed.

Trade and prosperity picked up after the war. Having been fourth in port activity, New York jumped to first place in the 1790s, although there were setbacks, particularly Jefferson’s Embargo and the War of 1812. After the war ended in 1815, peace restored prosperity as British merchants sent mass shipments of goods, including ceramics, to New York. Some goods went directly to merchants but many were sold by auctioneers. In 1817 the state legislature authorized the building of the Erie Canal, which transformed trade by funneling resources from the Midwest to New York instead of other coastal cities. Immigration from Europe increased exponentially, initially mostly from Ireland and Germany and then southern and eastern Europe, along with other parts of the United States.[6] With population growth came changes in the city’s social geography (fig. 3). Whereas in the eighteenth century, employers and slave owners lived under one roof with their employees and captives in neighborhoods that were relatively heterogeneous by economic class, in the nineteenth century they moved away from their workplaces and workers, and established residential enclaves that were quite homogenous by class. The enslaved, who were finally emancipated in New York in 1827, and other workers established their own neighborhoods, and the face of the city was irrevocably changed.

In spite of the fact that Manhattan Island is one of the most intensively occupied spaces in the world, archaeological remains can be found under existing buildings and streets, especially where wetlands, shorelines, and low-lying ground have been filled in.[7] The first archaeologists to work in the city, at the turn of the twentieth century, searched the water’s edge for Native American sites and scoured undeveloped upland areas for Revolutionary War artifacts. The most intensive period for urban archaeology in the city began during the building boom of the late 1970s, when city, state, and federal laws first required developers to conduct environmental studies, which included archaeology (fig. 4).[8] This period lasted until the early 1990s, although projects continue today.[9]

The Native American Presence

When Native Americans first arrived in the area after the retreat of the last glaciers, sea levels were much lower, and the Atlantic shore was 24 to 60 miles to the east of what is now New York City. As sea levels rose, the area became very rich in marine, estuarine, and riverine resources of fish, shellfish, and sea mammals, as well as migratory birds.

The richness of the environment precluded a major reliance on agriculture, unlike other areas of Native populations.[10] But like other groups, the local people adopted pottery making more than 2,000 years ago, an innovation that had a profound effect on Native lifeways. In the early twentieth century, avocational archaeologists Reginald Bolton and William Calver discovered a nearly complete jar from the Late Woodland period (A.D. 900–1600) at approximately 214th Street east of Tenth Avenue, the Inwood area of upper Manhattan (figs. 5, 6).[11] Avocational archaeologists have contributed much of what we know about New York’s archaeological past. Their work was particularly important in the early twentieth century, when the city was being developed at an alarming rate and many of its archaeological sites were destroyed.[12]

Dutch Cooking Pots

Three-legged cooking pots with one or two distinctively shaped ear handles are the most common coarse earthenware vessels found on North American seventeenth-century sites where the Dutch established colonies or traded extensively.[13] Earthenware cooking pots were used to prepare many types of foods, especially grain gruels or porridges, or soups and stews. Grain gruels were an important part of seventeenth-century Dutch foodways, and Dutch settlers in New Amsterdam added Native American “sapaen,” or cornmeal porridge, to their diets as a substitute for wheat or barley gruels.[14] Although government and laws changed when New Amsterdam became New York under the English, foodways did not.[15]

In archaeological examples and contemporary genre paintings, most cook pots are made of red earthenware, but some are made of buff or white clay (fig. 7). Lead glaze, which appears yellow on the buff-bodied pots, covers the interior and about two-thirds of the exterior. Red pots sometimes have white slip under a green glaze on the interior and sometimes are decorated with trailed slip motifs on the exterior.[16]

Two cooking pots excavated from a mid-1690s deposit at the 7 Hanover Square site in lower Manhattan are evidence that Dutch ceramics, and by extension Dutch foodways, were in use more than a generation after the English takeover (fig. 8).[17] The buff-bodied pot was almost certainly imported from the Netherlands, but the red-bodied vessel might have been made in New York, a possibility to be explored using various material science analyses.[18]

Africans in New Amsterdam—Delft Plate

The first enslaved Africans were brought to New Amsterdam in 1625 or 1626 by the Dutch West India Company, but their presence has tended to be excluded from traditional histories (fig. 9). Recently, however, archaeologists have been looking for traces of African presence in excavations and collections.[19] In 1984, archaeologists digging at the Broad Financial Center site in the heart of what had been New Amsterdam uncovered the lower portion of a barrel containing a cache of objects, including half of a faience plate, an assortment of stoneware marbles, a large iron key, iron nails, tobacco pipe fragments, several other sherds, and wampum (fig. 10).[20] The plate was made by Haarlem potter Gerrit Verstraeten and dates to the mid-seventeenth century, dating the feature to that period (fig. 11).[21] The pattern was derived from a Chinese porcelain style transitional from the Ming to Qing dynasties.

A visiting Dutch avocational archaeologist identified the barrel—which had holes punched through its base—as a drain, a common seventeenth-century feature in the Netherlands. But what about the objects in it? Were they items that had simply randomly accumulated in the drain?

Based on discoveries made at later African-American sites in the South, the value of some of the objects in a distant frontier outpost like New Amsterdam, and contemporary religious practices in western Africa, it is likely that the barrel and its contents constituted something very different: a spirit cache created by an African. Slaves might have ritually used objects that were new to them—European ones—but which had traditional values or characteristics, such as the color white or material such as iron.[22]

Drinking at the King’s House Tavern

Taverns were extremely important in social, political, and economic life in the Dutch and English American colonies (fig. 12). They were the only large buildings in which groups of people could gather for secular purposes; they socialized, heard the news, conducted trade deals, discussed political issues, flirted, and, of course, drank. Excavations at the Stadt Huys Block at 85 Broad Street in lower Manhattan uncovered the foundation wall and basement deposits from the King’s House Tavern, which was built in 1670, used as a temporary City Hall when the Stadt Huys next door was declared unsafe, and burned in 1706.[23] When the tavern was demolished, the broken glass bottles, white clay smoking pipes, and drinking vessels wound up in the basement. Among the archaeological fill, five nearly identical red earthenware jugs were retrieved (fig. 13).[24]

The five jugs were almost certainly made by the same local potter, who copied a stoneware or tin-glazed form.[25] These are noteworthy examples of early American-made ceramics, but they exhibit characteristics of less-than-perfect domestic production. Two of the jugs have thick glaze and kiln-pad adhesions on their bases that make them rather unsteady. They have different colored glazes, due in part to varying firing conditions within the wood-fired kiln, although the green, copper oxide glaze of one shows that at least two different glaze formulas were used.

The capacity of the jugs varies from approximately 3 2/3 cups to 4 1/4 cups. Wine and beer usually were shipped and stored in barrels and tapped as needed. Perhaps patrons who were in the know would ask for their drink to be served in the green earthenware jug rather than the light brown one because it held a little more.

Eighteenth-Century Stonewares

Ceramic historians know the names of Crolius and Remmey as the two most famous potting families in North American salt-glazed stoneware manufacture. Their New York City potteries, located just north of the Common (now the site of City Hall), began operation in the 1720s.[26] The nineteenth-century vessels made by these interrelated families are well known because many were marked or decorated with distinctive motifs, but the families’ earlier products are known mainly from archaeological excavations of waster dumps uncovered at sites near the potteries.[27] In the eighteenth century the potters worked together with their families and apprentices to make vessels that imitated tin-glazed and white salt-glazed forms in an effort to capture part of the growing market for ceramics. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, however, the market for salt-glazed stoneware vessels narrowed, and potters concentrated on making jars, jugs, and chamber pots.[28]

The remarkable New York–made barber’s bowl in figure 14 has a distinctive cutout and rather crude versions of painted motifs—a pair of scissors, a straight razor, and a brush or powder puff—frequently seen on tin-glazed examples.[29] Although the base is missing, the Manhattan potters were copying a common tin-glazed form with a deep base, like the example seen in figure 15. Other bowl-shaped vessels with decorated everted rims were likely made as washbasins, based on their resemblance to tin-glazed examples.[30] Fragments of at least a dozen washbasins, all with slightly different painted rim motifs but essentially identical forms, were found in the City Hall Park waster deposit.

The Revolution in New York City

Before the war, some citizens were enthusiastic about the pro-colonial policies of William Pitt (the Elder),[31] as witnessed by the “Patriotick Barber” cartoon (see fig. 15) and a punch bowl with “Pitt and Liberty” (fig. 16).[32] Many people in the city retained their patriotic stance after war broke out. When Washington and his troops were forced to evacuate the city in late 1776, however, the British made it their headquarters and did not leave until 1783.[33] Patriots left their homes and businesses in the city while Loyalists from other colonies flocked here for the protection of the Crown.[34] Some officers were quartered in the abandoned homes of patriots; others, along with enlisted men, had quarters in the barracks on the Common.[35]

Recent archaeological excavations on the site of the barracks have uncovered artifacts from a midden associated with the British occupation, including a “chintz” painted creamware teapot, an ebullient style of decoration rarely found on archaeological sites in America (fig. 17).[36] It was probably part of the outfit of an officer, for his personal use. Based on its shape and decoration, the teapot might have been made at the factory of William Greatbatch in Staffordshire, or the Leeds pottery in Yorkshire. Ceramic historians have attributed this style of decoration to the London shop of David Rhodes, but it was copied by other enamelers who worked on site at potteries in both Staffordshire and Yorkshire.[37]

Landfill and a Ceramic Dump

Real estate has always been important in New York’s economy, and throughout its history land has been created by landfilling to increase space at the city’s center. The first large-scale landfill occurred in the early 1690s along the East River. Landfilling continued there into the early nineteenth century, eventually adding three blocks to the city’s east side (fig. 18).[38] Landfilling along the west side began in the early nineteenth century and continued into the late twentieth century with the construction of Battery Park City into the Hudson. To make land during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, large wooden frames were built at the water’s edge, floated out, and sunk, enclosing an area that was then filled with earth (from leveling nearby hills or digging basements) and garbage. Refuse of all sorts was a large part of landfill until the early nineteenth century, when health considerations ended the practice. The refuse in landfill is a bonanza for archaeologists.[39]

The pearlware painted and small bowls illustrated in figure 19 are part of a ceramic dump assemblage found in landfill in Whitehall Slip.[40] In this particular assemblage, there were at least fifteen small bowls, two saucers, and one teacup with this tulip pattern.[41] They were probably part of a shipment of ceramics damaged during its transatlantic voyage; ceramics and other goods were often auctioned off directly at or near the docks, and it would have been convenient to dump damaged goods into the nearby landfill.[42] Like the contents of a shipwreck, this dump provides a unique snapshot of ceramics imported at one moment in time.

Commerce and Ceramics

Commerce has always been central to New York City’s existence. Although ceramics were but a small part of that trade, dishes from different parts of the world have been found in commercial and domestic archaeological contexts throughout all periods of the city’s history. The majority came from Great Britain, but porcelain from China was also popular.

Unlike Philadelphia and Boston, New York did not have a thriving local earthenware industry for much of the eighteenth century.[43] As a result, British-made slip-decorated coarse earthenwares are relatively more common in colonial archaeological assemblages there.[44]

Before the Revolutionary War, Chinese porcelain came to America through British merchants. After the war ended, American merchants made haste to establish their own trade relationships with Chinese merchants.[45] The teabowl shown in figure 20, with the motif of two lovebirds on a bar, was found in a large domestic deposit associated with the Bowne family.[46]

New Yorkers continued to prefer imported British ceramics to American-made ones well into the nineteenth century. The ca. 1842–1855 Staffordshire-made teapot illustrated in figure 21 was found at Seneca Village, an African-American and Irish immigrant community located in today’s Central Park. This elegant vessel was found in association with African-American homes and belies the denigrating stereotypical descriptions of black New Yorkers published in contemporary newspapers.

The Domestic Revolution

Before the mid-nineteenth century, middle-class white women in New York continued to follow the lead of their British cousins and chose transfer-printed dishes for setting their tables. But in the 1840s they broke away from this British tradition and began to use plain white plates in paneled Gothic-style patterns for family meals, and fancy porcelain cups for entertaining their friends.[47] The ecclesiastical associations of the Gothic style perhaps underlined women’s role as the moral guardians of society, while the fancier teawares enhanced their role of negotiating their family’s position in the social structure.[48] American women used the decorative arts to express a new identity, distinct from the older colonial identity that had tied the British colonies to the mother country. It wasn’t until five decades after independence that American women began to stop regarding English women as the arbiters of taste for fashions in the decorative arts, a phenomenon common among former colonists after achieving independence.[49]

The archaeologically recovered ceramics illustrated in the figures shown here come from a privy associated with the Robson family living on fashionable Washington Square.[50] The blue-on-white cup and saucer (fig. 22) and Willow-patterned plate (fig. 23) come from a lower deposit, dating to the 1840s, while the Gothic-style plate (fig. 24) and Italianate-style cup and saucer (fig. 25) come from an upper layer, deposited in the 1850s. The porcelain cup and saucer are unmarked and could have been made in either Europe (probably France) or the United States.[51]

Irish Immigration

The nineteenth century saw an unprecedented influx of immigrants to New York City, contributing to an increase in population from 33,000 in 1790 to 1.5 million in 1890. For much of those 100 years, the Irish constituted the largest group of immigrants, a position ceded to the Germans only later in the century.[52]

In the early 1990s, archaeologists excavated in the old Five Points district (fig. 26), the city’s most notorious slum. They uncovered a privy associated with a tenement occupied by Irish immigrants throughout the mid- to late nineteenth century, and discovered a host of domestic and other materials. The ceramics included transfer-printed teawares in a variety of patterns and plates with the blue Willow pattern as well as white granite in the Gothic style—both common in contemporary middle-class homes.[53]

The printed teawares included a “Father Mathew Temperance” cup (fig. 27). Father Mathew (1790–1856) was a temperance leader in Ireland whose goal was to rid the poor of intemperance so they could improve themselves spiritually, emotionally, and physically. A local priest invited Father Mathew to preach at Five Points when he was traveling in the United States, but it is not known whether he accepted the invitation.[54] The cup’s meaning in the tenement home is ambiguous. Was its role to inculcate temperance among household members and their guests, or was it to flaunt temperance? Did someone sip their whiskey from it? In the twenty-first century its importance assumed a new meaning, as one of the few artifacts from the collection to survive the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001.[55]

The territory claimed by the Dutch as the colony of New Netherland extended from roughly the Connecticut River in the north to the Delaware River in the south. New Amsterdam was its administrative center.

Historian David Cohen has estimated that almost half of the immigrants to New Netherland were not Dutch but came from neighboring areas of Germany, France, the Southern Netherlands, and Scandinavia. David Steven Cohen, “How Dutch Were the Dutch of New Netherland?” New York History 62, no. 1 (January 1981): 43–60.

England’s 1664 takeover of New Netherland is well known; less well known is its recapture by a Dutch fleet in 1673. It was permanently ceded to England the following year in return for English concessions in the Caribbean. Both the initial English conquest and the Dutch recapture were part of the Anglo-Dutch Wars fought to determine which nation would control world trade.

Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 122.

As the eighteenth century progressed, enslaved Africans constituted 14–21 percent of the city’s population. There was at least one slave revolt, in 1712, and rumors of more.

The city’s population grew from approximately 60,000 in 1800, to more than 500,000 in 1850, to more than 1.85 million in 1900.

The city comprised only Manhattan until 1898, when Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island joined it as the five boroughs of New York City. European settlement began at the southern tip of the island and gradually spread north over the next 300 years until the entire island, with the exception of some reserved parklands, was covered with structures and streets.

Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall, Unearthing Gotham: The Archaeology of New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 3–14.

Some of the reports that are listed below for projects from the 1980s until the present are on file at the City of New York Landmarks Preservation Commission and are available online at http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/html/publications/archaeology_reports.shtml (accessed May 19, 2017). They include: AKRF, Inc., URS Corporation, and Linda Stone, The South Ferry Terminal Project, Volumes I and II (2012); Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets, New York: The Barclays Bank Site (1987); Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, The Assay Site: Historic and Archaeological Investigations of the New York City Waterfront [Block 35] (1990); Michael L. Blakey, Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson, Barbara A. Bianco, and Edna Greene Medford, eds., The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York, Volumes I–III (2009); Charles D. Cheek and Daniel G. Roberts, eds., The Archaeology of 290 Broadway, Volumes I–IV (2009); Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants and URS Corporation, City Hall Rehabilitation—Archaeology Project 2010–2011 (2012); Joan Geismar, The Archaeological Investigations of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City (1983); Joel Grossman, The Excavation of Augustine Heerman’s Warehouse and Associated 17th Century Dutch West India Company Deposits (1985); Diana Rockman, Wendy Harris, and Jed Levin, The Archaeological Investigation of the TELCO Block, South Street Seaport Historic District, New York, New York (1982); Nan A. Rothschild, Diana Rockman Wall, and Eugene Boesch, The Archaeological Investigations of the Stadt Huys Block: A Final Report (1987); Nan A. Rothschild and Arnold Pickman, The 7 Hanover Square Excavation Report: A Final Report (1990); and Rebecca Yamin, Tales of Five Points: Working Class Life in Nineteenth-Century New York, Volumes I–VI (2002). The artifacts are housed at either the New York State Museum in Albany or the City of New York Landmarks Preservation Commission repository in New York City. A full list of the archaeology reports on file at the commission is available online at http: //www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/html/publications/arch_reports_list.shtml (accessed May 19, 2017).

Diana diZerega Wall and Anne-Marie Cantwell, Touring Gotham’s Archaeological Past: 8 Self-Guided Walking Tours through New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), p. 96; Cantwell and Wall, Unearthing Gotham, pp. 73, 105.

Reginald P. Bolton, “The Indians of Washington Heights,” in The Indians of Greater New York and the Lower Hudson, edited by Clark Wissler, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 3 (New York: AMS Press, 1909), pp. 77–109.

See William Louis Calver and Reginald Pelham Bolton, History Written with Pick and Shovel (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1950).

In the older New York City archaeology reports these vessels were called grapen. The term used now by Dutch archaeologists and ceramic historians for this type of vessel is kookpot (plural kookpotten) for both large and small forms.

Adriaen van der Donck, A Description of New Netherland: The Iroquoians and Their World, ed. Charles T. Gehring and William A. Starna, trans. Diederik Willem Goedhuys (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

Meta Janowitz, “Indian Corn and Dutch Pots: Seventeenth-Century Foodways in New Amsterdam/New York,” Historical Archaeology 27, no. 2 (1993): 6–24.

Jan Baart et al., Opgravingen in Amsterdam: 20 Jaar Stadskernonderzoek (Amsterdam: Dienst der Publieke Werken, 1977); Jerzy Gawronski, Amsterdam Ceramics: A City’s History and an Archaeological Ceramics Catalogue, 1175–2011 (Amsterdam: Lubberhuizen, 2012); John G. Hurst, David S. Neal, and H.J.E. van Beuningen, Pottery Produced and Traded in North-West Europe, 1350–1650, Rotterdam Papers 6 (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1986); Richard G. Schaefer, A Typology of Seventeenth-Century Dutch Ceramics and Its Implications for American Historical Archaeology, BAR International Series 702 (Oxford, Eng.: British Archaeological Reports, 1998); Charlotte Wilcoxen, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987). See also the collections of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen using its online ALMA database at http://collectie.boijmans.nl/en/onderzoek/alma-en (accessed May 19, 2017).

Rothschild and Pickman, 7 Hanover Square Excavation Report.

ICP (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry) is a destructive technique for analyzing the chemical composition of ceramic bodies. PXrf (portable X-ray fluorescence) is a nondestructive technique that also analyzes chemical composition. See Lindsay Bloch, “Made in America? Ceramics, Credit, and Exchange on Chesapeake Plantations,” Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (2015); Allan Gilbert, Garman Harbottle, and Dan deNoyelles, “A Ceramic Chemistry Archive for New Netherland/New York,” Historical Archaeology 27, no. 3 (1993): 17–56; Deborah L. Miller, Meta F. Janowitz, and Allan S. Gilbert, “Identifying Red, Brown, and Black Philadelphia ‘China’ through Compositional Analysis: Initial Results,” American Ceramic Circle Journal 19 (2017): 97–125; and J. Victor Owen and Denise Hansen, “Compositional Constraints on the Identification of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain Sherds from Fort Beausejour, New Brunswick, and Grassy Island, Nova Scotia, Canada,” Historical Archaeology 30, no. 4 (1996): 88–100.

Diana diZerega Wall, “Twenty Years After: Re-Examining Archaeological Collections for Evidence of New York City’s Colonial African Past,” African American Archaeology 28 (2001): 1–6.

These pieces of wampum—beads made from clamshells and used as currency—are the only ones found in any non-Indian archaeological site on Manhattan.

Jerzy Gawronski (Amsterdam City Archaeologist), personal communication, 2010.

See also Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall, “Looking for Africans in Seventeenth-Century New Amsterdam,” in The Archaeology of Race in the Northeast, edited by Christopher N. Matthews and Allison Manfra McGovern (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2015); and Diane Dallal, “Van Tienhoven’s Basket: Treasure or Trash?” in One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure, edited by Alexandra van Dongen et al. (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1996), pp. 215–23.

Rothschild, Wall, and Boesch, Archaeological Investigations of the Stadt Huys Block; Cantwell and Wall, Unearthing Gotham, pp. 155–58. This was the first major site excavated in New York City; its excavation proved that significant archaeological deposits remained, even in one of the most developed parts of the city. The footprints of the tavern and the Stadt Huys have been outlined in the plaza of the building erected on the site and part of the tavern’s foundation wall has been reconstructed there as well.

Diana Diz. Rockman (Wall) and Nan A. Rothschild, “City Tavern, Country Tavern: An Analysis of Four Colonial Sites,” Historical Archaeology 18, no. 2 (1984): 112–21. The other ceramics in the tavern assemblage were fragmentary. Twenty-four of the thirty-five sherds had identifiable forms, among them mugs and cups for drinking; the great majority of drinking vessels found were glass stemwares. See Fayden (Janowitz), “Indian Corn and Dutch Pots”; and Rothschild, Wall, and Boesch, Archaeological Investigations of the Stadt Huys Block.

European-trained potters were working in Manhattan by the mid-seventeenth century at the latest. See William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Pottery of New York State, 1650–1900, 2nd ed. (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987), pp. 35–38; and Meta F. Janowitz, Kate T. Morgan, and Nan A. Rothschild, “Cultural Pluralism and Pots in New Amsterdam-New York City,” in Domestic Pottery of the Northeastern United States, 1625–1850, edited by Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh (Orlando, Fla.: Academic Press, 1985), pp. 29–48. Most of the seventeenth-century potters were earthenware potters from the Netherlands. Dirck Claesen, from Leeuwerden in Friesland, was in New Amsterdam/New York from before 1655 to 1686. His stepsons John and Ewout Euwatse worked in Brooklyn before establishing themselves in Manhattan in 1695 and 1716, respectively. Sampson Bensen and his son Dirck came from Haarlem sometime before 1698. Dirck died between 1725 and 1726 and his father did not long survive him. Another early potter was English (see Ketchum, Potters and Pottery of New York State, p. 39). John DeWilde was brought over by Daniel Coxe of New Jersey to work in a short-lived (ca. 1688–1692) faience manufactory in Burlington, New Jersey. After the failure of this pottery, DeWilde apparently came to New York for a time but died in New Jersey in 1704. The neck treatment on the tavern jugs is similar to some German non-Bellarmine stoneware jug necks. See David R. M. Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900: Archaeology and Cultural History (London: British Museum Press, 1997), pp. 85 (fig. 3.46 #11), 107 (fig. 3.69) and 108 (fig. 3.70), although those vessels were made in the sixteenth century; and J.G.N. Reynaud, Rhodesteyn, Schatkamer der Middeleeuwse Ceramiek [Guide to the Collections at the Rhodesteyn Museum], booklet (Utrecht, Netherlands: Neerlangbroek, n.d.), ill. 3. The white faience jug shown in Gerard ter Borch’s Woman Drinking Wine with a Sleeping Soldier, ca. 1662, has a similar neck.

Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66.

Meta F. Janowitz, “Appendix D: List of Stoneware Vessels,” in Cheek and Roberts, Archaeology of 290 Broadway; and “Appendix F: Analysis of Local Stoneware and Kiln Furniture from the Grave Shafts,” in Warren Perry, Jean Howson, and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., The Archaeology of the New York African Burial Ground, Part 3: Appendices (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press in association with the U.S. General Services Administration, 2009); Meta F. Janowitz and Charles D. Cheek, “The New York Ceramic Industry and Its Use of the Burial Ground,” in Cheek and Roberts, Archaeology of 290 Broadway, vol. 1.

For example, the only forms listed on an early-nineteenth-century Clarkson Crolius broadside, which can be found online at http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/broadsides_bdsny11271/ (accessed May 19, 2017), are pots, jugs, jars, pitchers, mugs, oyster pots, chamber pots, kegs, churns, and “Fountain and common Inkstands.”

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), pp. 236–38.

As John Austin explains, “Washbasins, sometimes called ‘wash hand basins’ in eighteenth-century documents, are generally distinguished from other bowls by their minimal or lack of exterior decoration and their everted rims, which would allow the basin to rest in the hole of a washstand.” Ibid., p. 239, fig. 580. They could have been used as mixing or serving bowls, of course, but their intended function was probably for washing. It is unlikely they were made as pans for baking food, because stoneware is less suitable for cooking than red earthenware, especially over an open hearth.

Pitt was prominent in the British government in the 1750s and 1760s, serving as leader of the House of Commons and, briefly, as prime minister. Even after his resignation in 1768, he supported the American colonists by opposing plans for taxing them anew. Ultimately, however, he was a proponent of empire, and did not support the colonists’ quest for independence.

At least four punch bowls with the Pitt inscription were recovered from Feature 34 at the 175 Water Street Site. See Geismar, Archaeological Investigations of the 175 Water Street Block, p. 392.

November 25, Evacuation Day, was celebrated for many years in New York City with patriotic fervor equal only to the Fourth of July.

The population of New York City in 1775 was approximately 25,000, but within a year it had plunged to about 3,000. By 1778, however, the influx of British troops and Loyalist refugees brought the number up to about 33,000.

The Common was an open public area, located at what was the northern end of the city during the eighteenth century. It was also the site of several municipal institutions, notably the Almshouse and the Gaol. The main barracks were built in 1757. Archaeological excavations have been conducted here in conjunction with various site improvements to the ca. 1805–1811 City Hall. See H. Arthur Bankoff and Alyssa Loorya, The History and Archaeology of City Hall Park (2008), and Alyssa Loorya, Daniel Eichinger, Meta F. Janowitz, and Matthew Brown, City Hall Rehabilitation—Archaeological Project (2013), both reports on file at the City of New York Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Robert Hunter, personal communication, November 2016. We’d like to thank Alyssa Loorya for calling this teapot to our attention and for her overall help with the City Hall Park collections.

David Barker, William Greatbach, a Staffordshire Potter (London: J. Horne, 1991), pp. 204–5.

Cantwell and Wall, Unearthing Gotham, pp. 224–43.

See the following reports, which are on file at the City of New York Landmarks Preservation Commission and available online at http://www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/html/publications/archaeology_reports.shtml: AKRF et al., Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets, New York; Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, The Assay Site; Geismar, Archaeological Investigations of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City; Rockman, Harris, and Levin, Archaeological Investigation of the TELCO Block; and Rothschild and Pickman, 7 Hanover Square Excavation Report. See also Joan H. Geismar, “Digging into a Seaport’s Past,” Archaeology 40, no. 1 (January/February 1987): 30–35; and Joan H. Geismar, “Landfill and Health, a Municipal Concern or, Telling It Like It Was,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 16 (1987): 49–57, available online at http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/neha/vol16/iss1/3 (accessed May 19, 2017).

The portion of Whitehall Slip excavated for this project had been built in three episodes, ca. 1734, ca. 1785, and ca. 1796. It was filled in gradually, ca. 1788, 1801–9, and before 1845. The ceramic dump is probably associated with the 1801–9 episode. The deposit of ceramic sherds was approximately 30 feet long and two feet thick. At least 95 pearlware vessels were in this dump assemblage: at least 61 have polychrome underglaze–painted motifs and another 15 have dipped motifs (AKRF et al., South Ferry Terminal Project, pp. 6-55–6-58). With the exception of the tulip motif illustrated here, the polychrome-painted floral patterns are small-scale motifs very similar to those identified at many other sites within the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Jonathan Rickard, personal communication, 2014, who has excavated waster deposits at the Enoch Wood and Sons ca. 1818–1846 pottery site in Staffordshire, is of the opinion that this motif was used at this factory and possibly also at its predecessor, Wood and Caldwell (ca. 1790–1818). Based on the date of the fill, an attribution to Wood and Caldwell is likely.

Twelve other bowls, however, share a pattern of blue-gray slip bands with rouletted checkerboard borders.

During the early nineteenth century, some merchants were direct importers of goods (including English ceramics) from manufacturers or wholesalers, while others acted as jobbers, buying goods at auction. Auction sales were commonly held in auction houses or coffeehouses located near the docks or on dock-side streets. In 1799 a committee appointed to comment on the unhealthy state of the dock area stated, “The open space between Water Street and the head of the Old Slip is recommended as a proper place for the sale of ship’s tackle and materials, earth ware in crates, hogsheads or bulk, and every other place for the sale of those articles at auction whether damaged or not, should be prohibited.” (The City of New York, Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784–1831 [New York: City of New York, 1917], 18:503.) Whether purchased by an importer or put up for sale at an auction, this particular shipment of English ceramics was probably found to be damaged on arrival and was disposed of by using it as part of the fill that closed off this portion of Whitehall Slip.

Ketchum, Potters and Pottery of New York State.

AKRF et al., South Ferry Terminal Project; Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets, New York; Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, The Assay Site; Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants and URS, City Hall Rehabilitation; Geismar, Archaeological Investigations of the 175 Water Street Block; Grossman, Excavation of Augustine Heerman’s Warehouse; Rockman, Harris, and Levin, Archaeological Investigation of the TELCO Block; Rothschild, Wall, and Boesch, Archaeological Excavations of the Stadt Huys Block; Rothschild and Pickman, 7 Hanover Square Excavation Report. For Philadelphia and Boston sites, see Charles H. LeeDecker, Edward M. Morin, Ingrid Wuebber, Meta Janowitz, Marie-Lorraine Pipes, Nadia Shevchik, Mallory Gordon, and Diane Dallal, The Meadows Site (36Ph35) Archaeological Data Recovery Program, I-95 Completion Project, Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, prepared for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Engineering District 6-0 and the Federal Highway Administration (1991); Richard J. Dent, Charles H. LeeDecker, Meta Janowitz, Marie-Lorraine Pipes, Ingrid Wuebber, Mallory A. Gordon, Henry M. R. Holt, Christy Roper, Gerard Scharfenberger, and Sharla Azizi, Archaeological and Historical Investigation of the Metropolitan Detention Center Site (36 PH 91), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1997), prepared by Louis Berger & Associates for the U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Washington, D.C.; and Michael Alterman and Richard M. Affleck, Archaeological Investigations at the Former Town Dock and Faneuil Hall, Boston National Historic Park, Boston, Massachusetts (1999), final report prepared by Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group for the Eastern Applied Archeology Center, Denver Service Center, National Park Service.

David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York: The New-York Historical Society, 1984); Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain in North America (New York: C. N. Potter, distributed by Crown Publishers, 1986).

This motif has been found on teawares given at or associated with marriage. For example, parts of a Chinese porcelain tea set with this central motif are in the collections of the New-York Historical Society. The vessels, which have a border of “blue enamel and gilt star pattern and blue enamel linked diamonds and gilt circles,” were given by Clarkson Crolius (1773–1893), a New York stoneware potter, to his wife, Elizabeth Meyer, around the time of their marriage in 1793; see http://www.nyhistory.org/exhibit/tea-bowl-and-saucer-1. The Bownes were druggists who had their shop and residence on Hanover Square in the early nineteenth century. See Louis Berger & Associates, the Cultural Resource Group, Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets; and Diana diZerega Wall, The Archaeology of Gender: Separating the Spheres in Urban America (New York: Plenum Press, 1994).

Lynne Sussman, The Wheat Pattern: An Illustrated Survey (Ottawa, Ont.: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, 1985); Diana diZerega Wall, “Sacred Dinners and Secular Teas: Constructing Domesticity in Mid-19th-Century New York,” Historical Archaeology 25, no. 4 (December 1991): 69–81; and Susan Lawrence, “Exporting Culture: Archaeology and the Nineteenth-Century British Empire,” Historical Archaeology 37, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 20–33.

Wall, Archaeology of Gender.

Kariann Yokota, “Postcolonialism and Material Culture in the Early United States,” The William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 2, 3rd ser. (April 2007): 263–70; Kariann Akemi Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Postcolonial Nation (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); and Lawrence, “Exporting Culture.”

Wall, Archaeology of Gender.

For examples of vessels made at Philadelphia and Brooklyn porcelain manufactories ca. 1830–1860, see Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain, 1770–1920 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), pp. 108–22. To date, no example of porcelain made in Brooklyn (or Philadelphia) has been identified in New York City archaeological assemblages, although this might have less to do with their absence than with the fact that those potteries did not usually mark their vessels. Future testing of vessels from nineteenth-century assemblages, such as has been done by J. Victor Owen for other porcelain, might bring some to light. See J. Victor Owen, “On the Earliest Products (ca. 1751–1752) of the Worcester Porcelain Manufactory: Evidence from Sherds from the Warmstry House Site, England,” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 4 (1998): 63–75, and J. Victor Owen, “The Geochemistry of Worcester Porcelain from Dr. Wall to Royal Worcester: 150 Years of Innovation,” Historical Archaeology 37, no. 4 (2003): 84–96.

Ira Rosenwaike, Population History of New York City (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1972).

Yamin, Tales of Five Points, vol. 1, report prepared by John Milner Associates, West Chester, Pa., for Edwards and Kelcey, engineers, and the U.S. General Services Administration, p. 102.

Stephen A. Brighton, “Prices that Suit the Times: Shopping for Ceramics at the Five Points,” Historical Archaeology 35, no. 3 (September 2001): 16–30; and “Collective Identities, the Catholic Temperance Movement, and Father Mathew: The Social History of a Teacup,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 37 (2008): 21–37, available online at http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/neha/vol37/iss1/3

The collection from the Five Points was housed in the basement of 6 World Trade Center, which was destroyed on that day. Fortunately, the Father Mathew teacup and several other artifacts were at an off-site exhibition and thus escaped harm. They are all that remains of the Five Points archaeological collection.