Aerial photograph of Jamestown Island showing seventeenth-century triangular fort and brick church tower at center right. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation.)

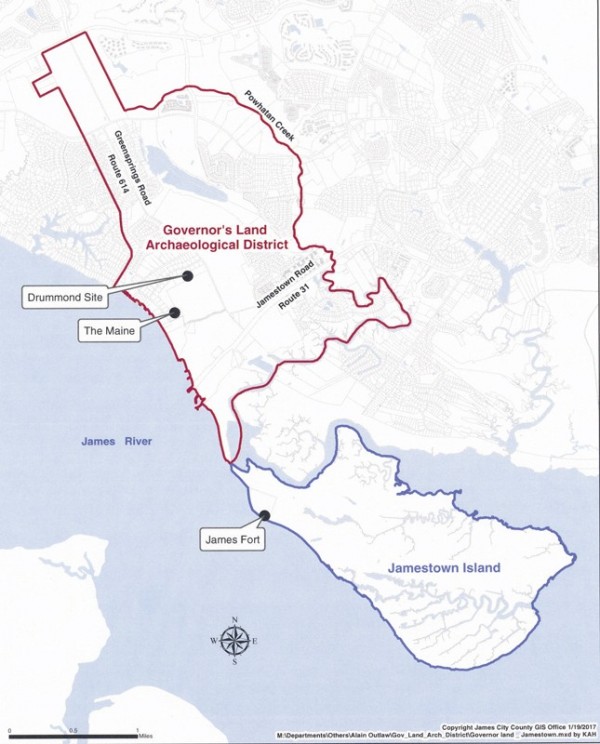

Map of the Governor’s Land Archaeological District and Jamestown Island, James City County, Virginia, 2017. (Courtesy, James City County GIS; mapping, Kim Hazelwood.)

Tobacco pipe, Robert Cotton, Jamestown, Virginia, 1608. Terracotta. L. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Michael Lavin.)

Three-bowl tobacco pipe, Dutch, 1618–1625. White ball clay. L. 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Drawing of the three-bowl tobacco pipe illustrated in fig. 4 depicting the multiple “EO” stamps of the maker. (Drawing, Alain C. Outlaw.)

Pipe fragment, Chibouk, Turkey, early seventeenth century. Earthenware. H. 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation and Colonial National Historical Park; photo, Hayden Bassett.) George Sandys traveled to Turkey in 1610 and was the first Englishman to describe the Turkish tobacco pipe, or chibouk.

Wine cup sherd, Jingdezhen, China, 1618–1625. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Christoffel van den Berghe (active Middelburg, Netherlands, ca. 1617–after 1628), Still Life with Flowers in a Vase, 1617. Oil on copper. 14 13/16 x 11 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection.)

Mug, Thomas Ward, Jamestown, Virginia, 1620–1635. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Cat jug fragments, London, England, 3rd quarter of seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Recovered in the 1970s during archaeological excavations of the William Drummond site.

Cat jug, London, England, third quarter of seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Cat jug fragment, England, mid-seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7/8" (Courtesy, York County Historical Museum; photo, Michael Lavin.) Only the lower left corner of the panel was found. It may have surrounded initials and a date.

Cat jug fragment, England, third quarter of seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) The eyes and nose of the cat are depicted on this small press-molded and polychrome decorated sherd.

Figural salt fragment, London, England, third quarter of seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Figural salt, London, England, dated 1673. Tin-glazed earthenware with polychrome decoration. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Dish, Portugal, fourth quarter of the seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 14". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This deep dish with lace motif was found on the Governor’s Land, and is similar to one from New Town excavations by the National Park Service on Jamestown Island.

Punch bowl, Portugal, third quarter of seventeenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 4 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Can, possibly Fulham, England, 1685–1695. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Courtesy, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and Jamestown Settlement; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Capuchine, possibly Fulham, England, ca. 1685–1720. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 3". (Courtesy Museum of London Archaeology Service; photo, Andy Chopping.) Found in Bishopsgate just outside of London, this small handled cup is similar in form to salt-glazed stoneware examples made in John Dwight’s Fulham factory in the last decade of the seventeenth century.

Gorge, John Dwight, Fulham, England, ca. 1685–1695. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 4". (Courtesy, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and Jamestown Settlement; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Jug fragment, John Dwight, Fulham, England, ca. 1675–1676. Brown salt-glazed stoneware. H. 2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Plate, London, England, 1689–1693. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo Robert Hunter.) After the Revolutionary War, Governor’s Land became the property of The College of William and Mary

Illustration showing a carved teabowl. Nottingham, England, ca. 1700. Salt-glazed stoneware. The fragments represent the only known Nottingham brown salt-glazed stoneware carved teabowl. (Drawing, Patty Munford.)

Gorge, Nottingham, England, ca. 1700. Salt-glazed stoneware H. 3 15/16". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) The ca. 1700 trade card of John Morley of Nottingham depicts a jug similar in form to this gorge, which is in the collections of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Teapot, China, 1745–1750. Slip-glazed porcelain. H. 3 1/2". (Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation and Jamestown Settlement; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Illustration of vessels from a soft paste Chinese porcelain tea set found on the Drummond site. (Drawing, Patty Munford.) Note that the finely painted bird and peony motif appears on both sides of the teapot.

Located thirty-five miles from the mouth of the James River in Virginia, Jamestown Island is renowned as the site of the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Sponsored by the Virginia Company of London as a commercial venture, one hundred and four men and boys arrived on the low-lying island on May 14, 1607, to found the Virginia colony for the English crown. Although the settlement was strategically located for protection against Spanish invasion, it was in Paspehegh Indian territory. More significantly, they settled in Powhatan Confederacy territory, Tsenacommach, which consisted of thirty tributary groups and up to 21,000 people under the rule of Chief Powhatan. The colonists were assaulted within a couple of weeks of their arrival, and tensions between them and the Paspeheghs were ongoing.[1]

Although the island foothold later became Virginia’s capital until 1699, its success was tenuous in the beginning. During the first three years, colonists died in high numbers from disease, bad water, food shortages, and Indian attacks. The colony narrowly escaped abandonment after the “Starving Time” winter of 1609–1610.[2]

Six days after arriving at Jamestown in 1607, George Percy traversed the mainland due north of the island. Colonial expansion on the mainland, however, did not commence until May 1611, when Sir Thomas Dale ordered “a blockhouse to be raised on the north side of our back river to prevent the Indians from killing our cattle.”[3] The demand for tobacco in England and the successful cultivation of tobacco by John Rolfe in 1612 prompted land development outside of Jamestown, and in 1617 Captain Samuel Argall established Argall Town, the first settlement on the mainland.[4]

In 1618 the Virginia Company instructed Sir George Yeardley to set aside three thousand acres on the “Main,” or mainland, “conquered or purchased from the Paspehegh Indians.” Thereafter known as Governor’s Land, the area included Argall Town and acreage for fifty tenants who came with Governor Yeardley. Tenants could keep half of their profits from cultivating the land; the other half would support the governor’s office and the Virginia Company.[5]

When the Virginia Company of London was dissolved in June 1624, Virginia became a Royal Colony and the tenant system on Governor’s Land was cancelled. The acreage was then leased by Virginia’s governors to the colony’s elite throughout the seventeenth century.[6]

A 1683 map shows the locations of eighteen plantations on Governor’s Land, one of which belonged to William Drummond. His plantation was located about halfway between Jamestown and Green Spring, Governor Berkeley’s plantation. Drummond was the first governor of the Province of Carolina, and he also served as sheriff of James City County and sergeant-at-arms of the Virginia General Assembly. In the 1676 rebellion led by Nathaniel Bacon against Governor Berkeley, Drummond supported Bacon and set fire to the governor’s house on Jamestown Island. Excavations of the Jamestown house revealed it was nearly empty,[7] while those on Governor’s Land indicated his plantation had been extensively occupied since circa 1650. Berkeley executed Drummond in 1677 and confiscated his estate. Drummond’s widow, Sarah, successfully fought to recover her material possessions, [8] and she and her family continued living on the plantation until well into the eighteenth century.

The year 2018 marks the quasquicentennial of the first historical archaeology excavations in James City County, Virginia. In 1893 the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (now Preservation Virginia), the nation’s oldest statewide preservation organization, acquired 22.5 acres around the island’s only seventeenth-century structure, a brick church tower (fig. 1). That year members of the association began excavating evidence of the overlapping colonial church foundations before constructing the Memorial Church to commemorate the tercentennial of Jamestown’s founding.[9]

Excavations on Preservation Virginia property occurred at various times throughout the twentieth century, and have been continuous since 1994. Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation archaeologists have uncovered the original 1607–1624 James Fort and related structures, and more than 2.5 million artifacts; more than 2,000 are showcased in the Archaearium, an onsite museum. The remaining 1,500 acres of Jamestown Island were acquired by the National Park Service in 1934. Excavations by Park Service archaeologists have occurred episodically in an area known as New Town since the 1930s, and many of their 1 million artifacts are displayed in Historic Jamestowne’s Visitor Center on Jamestown Island.[10]

Nearby, on the mainland north of and adjacent to Jamestown, a state-supported archaeological survey of Governor’s Land conducted in 1972 led to several excavations in the 1970s and 1980s by the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology (fig. 2).[11] Excavations included a circa 1618–1625 home lot called “The Maine,” and the circa 1648–1820 Drummond/Harris plantation. Collections from these sites are curated by the Jamestown/Yorktown Foundation, and several artifacts are on display in Jamestown Settlement’s Galleries at Jamestown.

Early-Seventeenth-Century Clay Tobacco Pipes at Jamestown and Beyond

Robert Cotton was the first Englishman to successfully work with clay in the New World (fig. 3). Listed in the ship’s manifest as a “Tobacco-pipe maker,” he arrived at James Fort in 1608, and because his name disappears from the documentary record he may have died during the Starving Time.[12] Cotton undoubtedly learned to make pipes of white ball clay in molds in London. However, unlike the English mold-made pipes with heels and small bulbous bowls, Cotton’s Jamestown pipes are handmade, and the bowls are large and tubular. They clearly resemble pipes made by Virginia Indians at that time.

Cotton’s pipes are numerous in Jamestown contexts dating to the Starving Time and before. They are made of iron-rich, light-brown firing clay and are identified by their form. Many are decorated on the stem in various patterns with impressed fleurs-de-lis. Four different metal stamps were used to mark the stems. One, a copper-alloy bookbinder’s stamp, was recovered from a 1610 context. Many stems are partially or completely octagonal-faceted and highly burnished. Nine stems are stamped with printer’s type with the names of prominent English investors in the Virginia Company—as, for example, one stamped “WILLIAM FALDOO” (William Faldo).[13] Cotton’s pipes were most likely made as a commodity to be sent to England, although, with one exception, they have not been identified outside of Jamestown.[14]

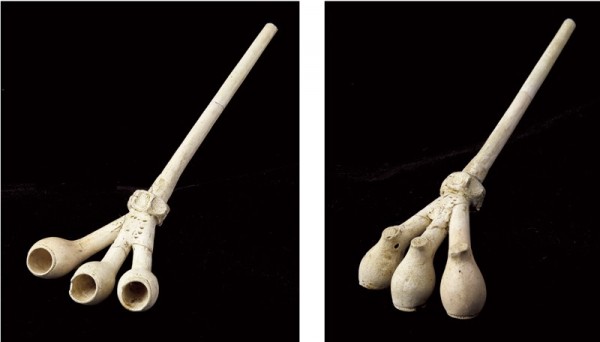

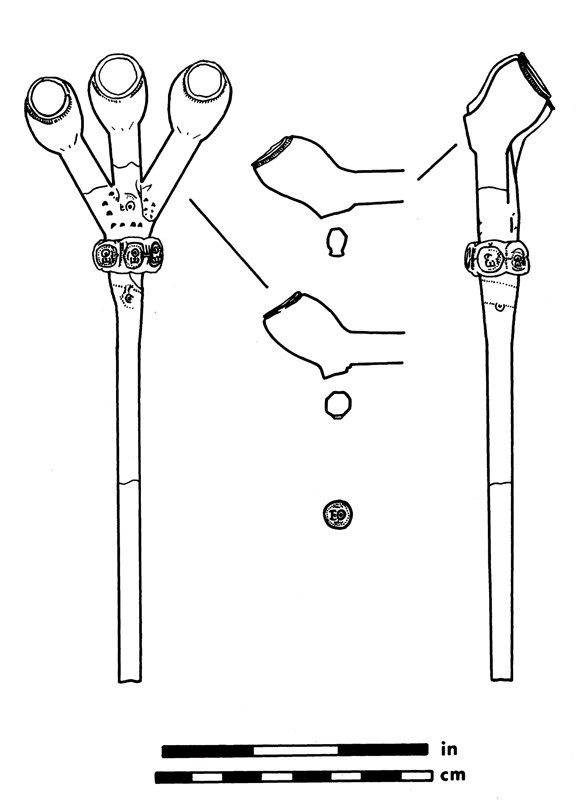

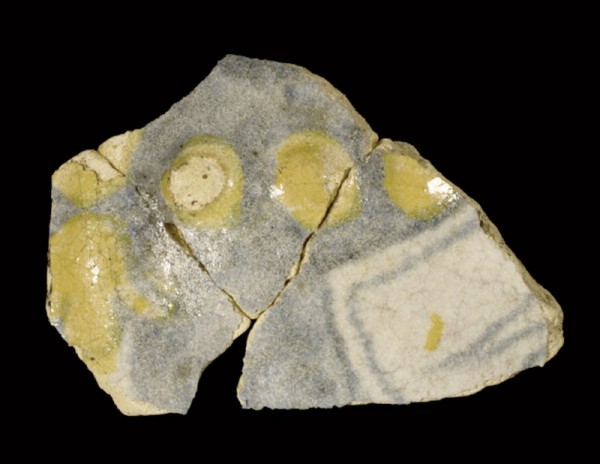

Believed to be Dutch, a white ball clay pipe with three bowls was discovered during excavations of “The Maine,” the 1617–1625 tenement dwelling on Governor’s Land (fig. 4). The small bulbous bowls with milled rims were mold-made and joined to a single stem, and the joint was reinforced with a collar before firing. The unrecorded and unidentified maker’s mark “EO” within a beaded circle appears thirteen times on the pipe (fig. 5).[15]

When it was discovered in 1976, this pipe was unique in the Virginia material culture record of early-seventeenth-century Virginia. Less intact multi-bowl pipes have since been identified at other rural domestic sites of the second quarter of the seventeenth century in the James River Basin, including Flowerdew Hundred, Martin’s Hundred, and Kingsmill.[16]

Exceptional among the early-seventeenth-century clay tobacco pipes from Jamestown Island is a fragment of a chibouk, or Ottoman tobacco pipe (fig. 6). The fragment is decorated in relief with a section of an Arabic inscription that translates: “. . . every.”[17] It was recently recovered on the home lot of Captain William Peirce in New Town by Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists.[18]

Arriving in Virginia in May 1610 after being shipwrecked in Bermuda for almost ten months, Peirce served at various times as lieutenant governor, captain of the guard, commander of Jamestown, and councilor before his death in 1647. His house, described as the “fairest” in New Town, was home to “Angelo,” the first named African at Jamestown in the 1620s, and in 1623 to the widely traveled George Sandys, treasurer of the Virginia Company.[19] This pipe fragment is one of the most significant artifacts to represent the cultural interaction and multinational exchange of people and commodities in early-seventeenth-century Virginia.

Chinese Porcelain Wine Cups

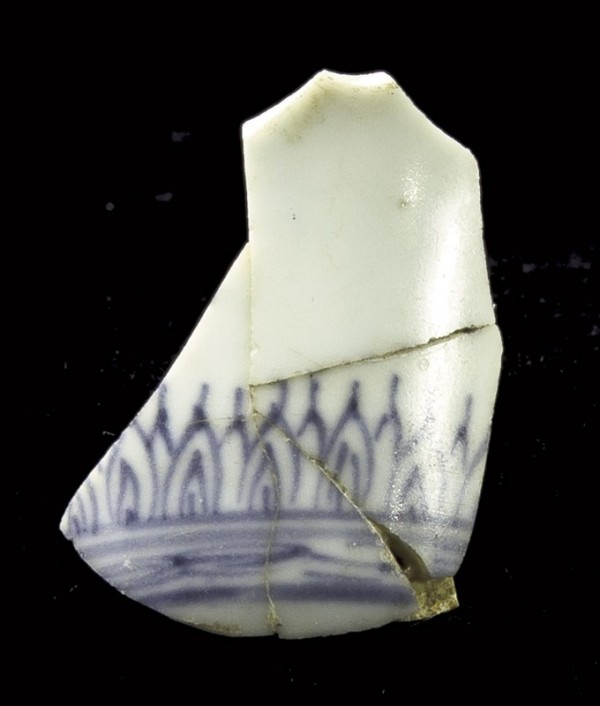

The recovery in 1976 of exotic Ming porcelain at The Maine on Governor’s Land was unexpected (fig. 7). This was, after all, the site of the governor’s tenant farmers living in a crudely constructed post-in-ground building on the frontier. Fragments from at least five of these fragile wine cups were discovered at the site.

Made in the latter part of Emperor Wan Li’s reign, the delicate, eggshell-thin cups are decorated in underglaze blue with a flame-and-scroll frieze. Their presence at The Maine suggests the site’s inhabitants were quickly accumulating wealth from raising tobacco during a boom period in Virginia.[20]

When the cups were recovered in 1976, Chinese porcelain scholars initially believed they dated to the 1640s. Shortly thereafter, a search for parallels in Dutch and Flemish paintings led to the discovery in the Philadelphia Museum of Art of a still-life painting by Christoffel van den Berghe that bore the date 1617 and included two flame-decorated wine cups (fig. 8). When museum curators were contacted for more information, the curator of Far Eastern Art thought the cups dated more comfortably from the middle of the seventeenth century, and that the 1617 date presented a conflict.[21]

Fortuitously, shortly thereafter Sotheby’s published a sales catalog of Chinese porcelain recovered from the Dutch shipwreck Witte Leeuw, an East Indiaman that sank in 1613 off the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic.[22] Wine cups paralleling The Maine examples were included, proving their early date.

Jamestown Cup

Thomas Ward is the first named English potter in the New World, and both documentary and archaeological evidence prove that he was working at the Martin’s Hundred settlement downriver from Jamestown in the 1620s.[23] Ward arrived in Virginia as an indentured servant in 1619, and was first seated on Governor’s Land. In 1620 he moved to Martin’s Hundred, where he made a wide range of lead-glazed coarse earthenware utilitarian vessels for the ever-increasing Virginia population.[24]

Ward may have been an itinerant potter, or possibly he trained a potter who worked at Jamestown Island circa 1619–1635. Similar or identical vessel forms were made at both locations and are identified by differences in their fabrics and glazes. Fine, well-blended alluvial clays distinguish the Jamestown pottery, as well as pinpricks in the lead glazes. While pottery made at Martin’s Hundred has been recovered locally from sites in James City County, the pottery made at Jamestown has been found on archaeological sites throughout Virginia’s tidewater region from as far away as the Northern Neck to the lower South side of the James River.[25] This globular drinking vessel is similar to cups made by potters working in the Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware tradition (fig. 9), however some of Ward’s other forms show influences from London-made vessels.[26]

Delft Figures

Known by many names, including faience, majolica, maiolica, and delftware, tin-glazed earthenware is among the most common found at sites in colonial Virginia. It is easily recognized because of its soft, chalky fabric, and by its thick and sometimes poorly adhering tin glaze. Forms are generally well recognized and consist primarily of fine table and drinking vessels.

An exception to the typical forms is an unusual press-molded cat jug that was discovered on the William Drummond site. It was recovered in numerous small fragments; one large section clearly shows the cat’s front feet (fig. 10). To represent fur, the exterior is hand painted with reddish-orange dashes separated by cobalt-blue stripes. A wash of copper-tinged green suggests that the cat is sitting in grass.

Seven intact and dated cat jugs ranging in date from 1657 to 1676 survive in museum and private collections (fig. 11).[27] The dates, and sometimes initials as well, appear within panels on the cat’s chest. All of the forms are hollow and, with a single exception, are open at the top so they could be used as containers.

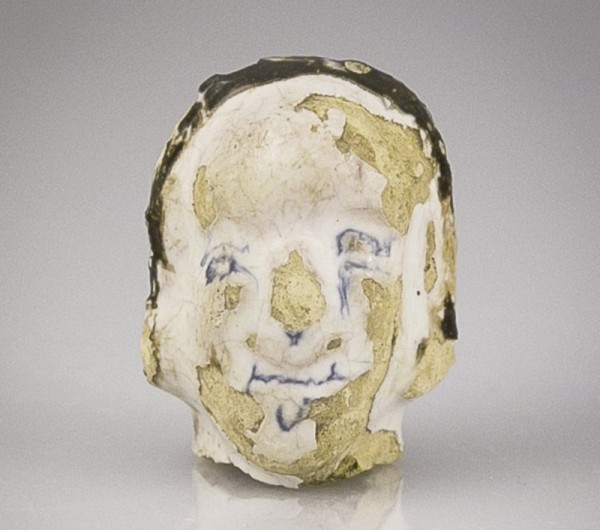

Since the Drummond cat jug was discovered in the late 1970s, sherds of only two other delftware examples have been excavated on Virginia archaeological sites. One small fragment was found in a seventeenth-century context in Yorktown on a site known as Chiskiack Watch (fig. 12). Decorated in blue and yellow, it includes dots and fur and a small part of the panel that may have included initials or a date.[28] The other example, recovered from a fill layer at Jamestown dating to the mid-seventeenth century, shows only the cat’s face (fig. 13).

Equally exceptional as the delftware cat jugs are fragments of a press-molded London delft figural salt excavated by Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists. Only two fragments—the head and part of a leg (not shown)—were recovered (fig. 14), and both are from disturbed contexts. Facial features are painted in cobalt blue, and manganese purple defines the hair or headdress. Tied with a ribbon outlined in cobalt blue and infilled with antimony yellow, the stockinged leg belongs to a male figure. Based on dated examples among the only five known intact English figural salts (fig. 15), this rare object was probably made in London between 1655 and 1680.[29]

Portuguese Faience Punch Bowl

Manufactured in Portugal as early as the mid-sixteenth century, tin-glazed earthenware, known as faience, appears frequently in the archaeological ceramic record in the Chesapeake region beginning in the second quarter of the seventeenth century.[30] Some might have arrived with colonists from England and some might relate to the Dutch, who were well established as traders in Virginia and Maryland into the third quarter of the seventeenth century.[31]

Faience vessels on Virginia sites dating circa 1625–1650 are typically hand painted in cobalt blue with chinoiserie motifs, armorial devices, or stylized curvilinear and geometric designs.[32] The most common forms are mugs, plates, and bowls. The recovery of a significant number of faience plates from the Thomas Pettus Plantation in James City County four miles downriver from Jamestown suggests that a set of tableware was in use by the high-status Pettus family after about 1640.[33]

Forms found in Virginia contexts from the third quarter of the seventeenth century include mugs, bowls, plates, fluted plates, and deep dishes. They are often distinguished by cobalt-blue chinoiserie motifs outlined in manganese, the so-called desenhos miúdos decorative technique that first appeared around 1640.[34] Dating as early as the mid-seventeenth century, lace patterns are common on faience of this period.[35] A large deep dish with lace decoration on the interior walls was found on a Governor’s Land site (fig. 16), and a similar one was recovered in the 1930s by the National Park Service from a site on Jamestown Island.[36]

At Jamestown in the 1930s, workers recovered what may be the earliest punch bowl yet from an Anglo-American colonial site (fig. 17). Manufactured of Portuguese faience, it is decorated on the exterior with two horizontal rows of cobalt-blue lace. Punch was first recorded in 1658 in an English dictionary, which described it as “A kind of Indian drink.”[37] The first mention of a punch bowl in Virginia is in an inventory dated 1682.[38] Since the consumption of punch by the English was in its infancy when this vessel made its way to Jamestown, it demonstrates that the island’s residents were up-to-date with the latest trends in alcohol consumption.

Slipware Mugs

Among the rarest wares found in Virginia and England are two cylindrical slipware cans (also “canns”) from the Drummond site (fig. 18). Sherds of only eight vessels like these have ever been reported, and all but one are cans that were found in or nearby Jamestown, Virginia’s major port in the seventeenth century. The only other reported object of this ware is a capuchine, which was found during excavations in London (fig. 19).[39]

Made of a fine, red earthenware, the vessels were wheel thrown, lathe trimmed, and fired twice. The mugs were spattered with oxides of manganese and tin. While the Drummond cans were also splashed with copper oxide, the Jamestown examples were splashed with cobalt oxide. The London capuchine bears a combination of tin- and cobalt-oxide splashes.[40]

Although their manufacture site is unknown, the slip-decorated earthenware vessels resemble stoneware forms made after 1685 at John Dwight’s Fulham factory. Dwight is recognized for experimentation with ceramics; however, archaeological excavations of his factory site uncovered no evidence of red earthenware production.[41] The slipped cans from the Drummond site were found in contexts that include a wide range of English tableware and Virginia-made utilitarian vessels, including a sizable assemblage of Dwight’s brown salt-glazed stoneware cans and gorges—the earliest documented Dwight assemblage in the New World.[42]

Many questions remain about these slip-decorated vessels that demonstrate a strong link to John Dwight.[43] Were they made at his factory, or were they made by an unidentified English competitor? Was Dwight’s lathe-turning technique stolen, or did these objects originate outside of England and serve as prototypes for Dwight’s cans and capuchines?

John Dwight Brown Stoneware in Virginia

Perhaps the largest assemblage of John Dwight’s brown salt-glazed stoneware in Virginia comes from the William Drummond site on Governor’s Land. The first Englishman to successfully produce stoneware in England, Dwight secured a patent for salt-glazed stoneware in 1672. From the 1670s until his death in 1703 he operated in Fulham, where he experimented with porcelain manufacture; copied Chinese dry-bodied stoneware, Frechen Bartmann jugs, and Westerwald-type blue and gray stoneware; and made both white and marbled stoneware.[44] The aforementioned slipware cans might also have been produced at Dwight’s factory.

Typical Dwight forms recovered from the Drummond site, as from other Virginia sites, are gorges (fig. 20), bottles, and tankards. Sarah Drummond might have ordered the vessels while in London, where she traveled to petition the king for the return of her possessions, which were confiscated by Governor Berkeley during Bacon’s Rebellion.[45] Dwight’s imitation German jugs were not found at Drummond, but a fragment of a jug medallion was found nearby at Barrett’s Ferry on the Chickahominy River. Associated with a tavern on the site, the find is highly significant because it represents the only Bartmann-type Dwight product in the New World. The cockerel on the medallion is a common motif used by Dwight on jugs and bottles for taverns in the 1675–1676 period (fig. 21).[46]

Delftware William and Mary Plate

Pottery became a medium for political statements in seventeenth-century England, and delftware was a favorite for depicting royal portraits and writing slogans. Elizabeth I was the first English monarch commemorated on a delftware dish. Dated 1602, it bears the inscription: “ROSE IS RED THE LEAVES ARE GRENE GOD SAVE ELIZABETH OUR QUEENE.” Charles I’s initials were painted on delftware items made during his reign, and his portrait appeared on delft even after his death. Thereafter, caricatures of every monarch appeared, mostly on tableware, until the end of delftware production in England.[47]

King William and Queen Mary ascended to the British throne in 1689, after the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. They jointly ruled until Mary’s death in 1694, which provides an end date of manufacture for a plate recovered from the Drummond site on Governor’s Land (fig. 22), and figured prominently locally: The College of William and Mary, the nation’s second oldest college, was named after the monarchs when it was founded in 1693. Also, Williamsburg was named for King William in 1699 when the capital was relocated there from Jamestown.

A large quantity of delftware made in this period was recovered during excavations of the Drummond site. The forms are wide-ranging and include plates, bowls, basins, teabowls, posset pots, and chamber pots. Their quantity and quality attest to the economic and social prominence of the family even after William Drummond was hanged in 1677 for participating in Bacon’s Rebellion. The William and Mary plate may have been obtained by his survivors to demonstrate their loyalty to English rule of law and to dispel notions of any future antigovernment activities by the family.

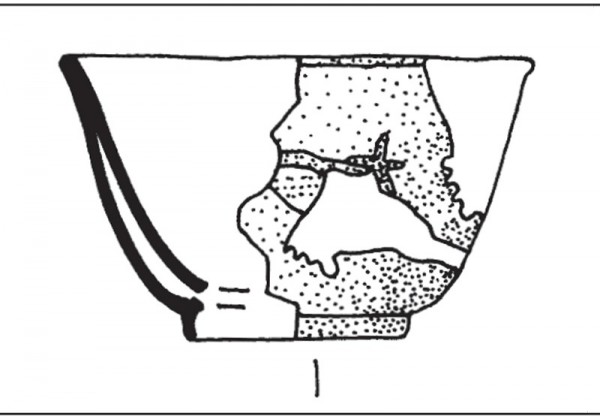

Nottingham Brown Salt-Glazed Stoneware Teabowl

Framents of a unique brown salt-glazed stoneware teabowl are also among the extensive collection of circa 1680–1710 English and locally made ceramics recovered from the Drummond site (fig. 23). The vessel is double-walled, and the outer wall was perforated with angular motifs when the clay was leather-hard before firing. Pierced, double-wall vessels are illustrated on a circa 1700 James Morely trade card, and the lustrous brown glaze is characteristic of Nottingham brown stoneware (fig. 24).[48]

It was not until the mid-seventeenth century that tea drinking was introduced to the English, appearing first as an expensive health drink in London coffeehouses.[49] As England’s first tea-drinking queen, Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705) is credited with making tea consumption de rigueur among the wealthy after she arrived in 1662. The recovery of this object at a time when tea was an expensive luxury item indicates that the ritual had arrived at the wealthy Drummond household long before it became affordable in most English and American households.[50]

Chinese Porcelain Teapot

The Drummonds continued living in their seventeenth-century vernacular earthfast home well into the eighteenth century, with the only improvements being the addition of rooms. However, the remarkable amount of fashionable ceramic tableware and teaware from the site indicates that they were wealthy and their tastes were up-to-date.

Linked with women, mass consumerism, and leisure time,[51] the tea ritual with its matching teabowls, tea saucers, and teapots, is well represented in the Drummond archaeological assemblage. The family’s ceramic choice for consuming the beverage was the most expensive and desirable of the period—Chinese porcelain.

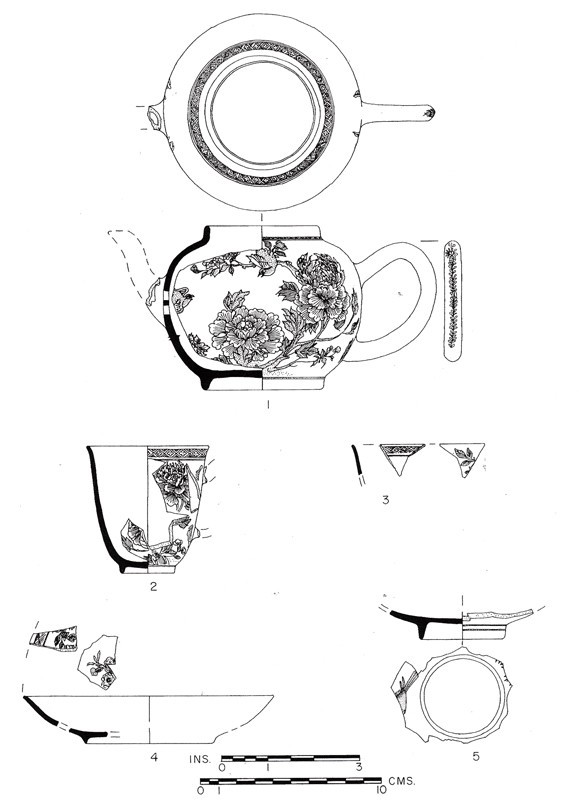

This teapot (fig. 25) is one of several items of a set found on the site, which included sherds of teabowls, saucers, and a sugar bowl. The thinly turned teapot and matching vessels are well painted with underglaze cobalt-blue floral motifs under a finely crackled glaze (fig. 26). Although it was identified in the early 1980s as Chinese soft-paste porcelain, Rose Kerr notes of the ware that the: “fine body has been termed ‘softpaste’ porcelain: it is in fact a standard hardpaste porcelain with an application of kaolin-rich slip on top to render the surface suitable for very fine brush painting.”[52]

William M. Kelso, The Buried Truth (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006).

Ibid., p. 20.

Alain C. Outlaw, “Governor’s Land: A Stewardship Legacy,” a newsletter of the Williamsburg Land Conservancy, Winter 2010, pp. 3–5.

Alain C. Outlaw, Governor’s Land: Archaeology of Early Seventeenth-Century Settlements (Charlottesville: Published for the Department of Historic Resources by the University Press of Virginia, 1990), p. 4.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 8.

William M. Kelso and Beverly Straube, 2007–2010 Interim Report on the APVA Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia (Richmond: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2008), pp. 52–64.

Wilcomb E. Washburn, “The Humble Petition of Sarah Drummond,” The William and Mary Quarterly 13, no. 3 (July 1956): 354–75.

Mrs. Parke C. Bagby, “Extracts from the APVA Yearbook 1900–1901,” in John L. Cotter, Archaeological Excavations at Jamestown: Colonial National Historic Park and Jamestown National Historic Site, Virginia, Archaeological Research Series 4 (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1958), pp. 219–24.

Cotter, Archaeological Excavations at Jamestown.

Outlaw, Governor’s Land.

David Givens, “Creating a Third Space: Material Culture, Colonialism, and Hybridity at James Fort,” submitted for the degree of Master of Arts, University of Leicester, June 2015, pp. 14–18.

William Kelso, Beverly Straube, and Daniel Smith, eds., 2007–2010 Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia, pp. 36–38, available online at http://historicjamestowne.org/download/field-reports-3/ (accessed September 18, 2017). A video presentation on the named pipes made at Jamestown by Robert Cotton, may be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6iNbq8db1w. The viewer experiences the moment of discovery of the William Faldoo pipe, and Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists discuss the significance of the named pipes found at Jamestown.

A Robert Cotton pipe stem on display in St. John’s Episcopal Church in Hampton, Virginia, was recognized by Beverly Straube. Found on a site known as the Second Church Site, it is clearly stamped multiple times with Cotton’s mark of fleur-de-lis within a diamond. Personal communication with Nick Luccketti, January 2017.

Outlaw, Governor’s Land, pp. 161–63.

Seth Mallios, At the Edge of the Precipice: Frontier Ventures, Jamestown’s Hinterland, and the Archaeology of 44JC802 (Richmond: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 2000), pp. 42–43. This manuscript is available online at http://Historicjamestowne.Org/Download/Field-Reports-3/ (accessed September 18, 2017).

I am deeply indebted to David A. Higgens, University of Liverpool, for confirming the identification and date of the pipe. Edmond J. Smith, University of Kent, referred me to his colleague Peter Good, also of University of Kent, who confirmed the script is Arabic in a Persian or Ottoman style, but most likely Ottoman. Much is written about chibouk smoking pipes, including examples with inscriptions, in the Journal of the Académie Internationale de la Pipe, available online at: http://pipeacademy.org/publications.html. For a history of smoking and chibouks in Turkey in the early 1600s, see Anna de Vicenz, “Chibouk Smoking Pipes—Secrets and Riddles of the Ottoman Past,” in Arise, Walk through the Land, edited by Joseph Patrich, Orit Peleg-Barkat, and Erez Ben-Yosef (Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society, 2016), pp. 111–19. Furthermore, the reed stem pipe style is believed to have been brought from North America to Africa via Sir John Hawkins, after which it became the typical pipe style in the Middle East by the early seventeenth century. See Rebecca C. W. Robinson, “Tobacco Pipes of Corinth and of the Athenian Agora,” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 54, no. 2 (1985): 150–51, http://www.jstor.org/stable/147907.

Cooperative Agreement #P16a01376 between the United States Department of Interior National Park Service and Preservation Virginia.

Martha McCartney, Jamestown Archaeological Assessment, 1992–1996: Documentary History of Jamestown Island, vol. 1: Narrative History (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2000), pp. 45–46. In 1615, after his travels to the Mediterranean and the Middle East, George Sandys published his travel journal, entitled Relation of a Journey (1615). For a synopsis of Sandys’s Virginia residency, see Mallios, At the Edge of the Precipice, pp. 15–19.

Outlaw, Governor’s Land, p. 54.

Personal communication with Irene Konfal, assistant to the curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976.

Sotheby’s conducted two auctions in 1977 of Chinese porcelain objects recovered from the Witte Leeuw. The first auction was by Sotheby Park Bernet & Co. in London on March 15, the second was held in Amsterdam by Sotheby Mak van Waay N.V. on April 27. The Rijksmuseum acquired several porcelain objects from the auctions, and in 1982 it published them in The Ceramic Load of the “Witte Leeuw” (1613), edited by C. L. van der Pijl-Ketel.

Martha W. McCartney, “The Martin’s Hundred Potter: English North America’s Earliest Known Master of His Trade,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 12, no. 2 (1995): 139–50. McCartney notes that Thomas arrived in Virginia on the Warwick in 1619. He was identified as a “Pottmaker” in a 1625 letter of complaint to Nicholas Ferrar, the treasurer of the Society of Martin’s Hundred. The last mention of Ward in the documentary record was on January 20, 1633/1634. The dates of his pottery production are circa 1619–1635. For an informative discussion of the coarse earthenware forms made at Martin’s Hundred and at Jamestown, see Beverly Straube, “The Colonial Potters of Tidewater Virginia,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 12, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 5–15.

Beverly A. Straube, “Ceramics in Early Virginia, Photo Essay,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), p. 12.

Matthew R. Laird, Nicholas M. Luccketti, and Merry A. Outlaw, Yorktown’s Buried History—From Chiskiack to the Civil War, booklet (Yorktown, Va.: Yorktown Historical Museum, 2017), pp. 51–52.

Straube, “Ceramics in Early Virginia, Photo Essay,” p. 12.

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1994), p. 285.

Laird, Luccketti, and Outlaw, Yorktown’s Buried History, p. 58.

Margaret K. Hofer “A Rediscovery at The New-York Historical Society,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2001), pp. 218–20. See also Leslie B. Grigsby, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, vol. 2: Delftware (London: Jonathon Horne Publications, 2000), pp. 236–37.

Tânia Manuel Casimiro, Mârio Varela Gomes, and Rosa Varela Gomes, “Portuguese Faience Trade and Consumption across the World 16th–18th Centuries,” in Global Pottery 1. Historical Archaeology and Archaeometry for Societies in Contact, edited by Jaume Buxeda i Garrigós, Marisol Madrid I Fernández, and Javier G. Iñañez (BAR International Series 2761, 2015), p. 67, available online at https://www.academia.edu/19605901/Portuguese_Faience_trade_and_consumption_across_the_World_16th_-18th_centuries (accessed May 15, 2017).

Lauren Kathleen McMillan, “Formation and the Development of a British-Atlantic Identity in the Chesapeake: An Archaeological and Historical Study of the Tobacco Pipe Trade in the Potomac River Valley, ca. 1630–1730,” Ph.D. diss., University of Tennessee, 2015, pp. 114–38.

Casimiro, Gomes, and Gomes, “Portuguese Faience Trade and Consumption,” p. 67.

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, Beverly A. Bogley, and Alain Outlaw, “Rich Man, Poor Man: Status Definition in Two Seventeenth-Century Ceramic Assemblages from Kingsmill,” paper presented to the annual meeting, Society for Historical Archaeology, Ottawa, Ontario, 1977.

Casimiro, Gomes, and Gomes, “Portuguese Faience Trade and Consumption,” pp. 68–69

Ibid., pp. 68, 79.

Cotter, Archeological Excavations at Jamestown, p. 184.

Edward Phillips, The New World of English Words, or, A General Dictionary Containing the Interpretations of Such Hard Words as Are Derived from Other Languages . . . (London: Printed by E. Tyler for Nath. Brooke, 1658), available online at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A54746.0001.001/1:10.15.11?rgn=div3;view=fulltext (accessed May 15, 2017).

Eleanor Breen, “‘One More Bowl and Then?’: A Material Culture Analysis of Punch Bowls,” Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology 28 (2012): 83, available online at http://mountvernonmidden.org/resources/JMAA_28_81_97-Breen.pdf (accessed May 15, 2017).

Jacqueline Pearce, “An Unusual Red Earthenware Capuchine from London,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 284–88.

Ibid.

Chris Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–79 (London: English Heritage Archaeological Report 6, 1999).

Janine E. Skerry and Suzanne Findlen Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America, (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2009), p. 76.

Merry A. Outlaw, “A Collection of Curious Canns,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), p. 208.

Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–79, pp. 121–22.

Washburn, “The Humble Petition of Sarah Drummond,” pp. 354–75.

Green, John Dwight’s Fulham Pottery Excavations 1971–79, pp. 112, 118–21, 199.

Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg, p. 28.

Skerry and Hood, Salt-Glazed Stoneware in Early America, p. 77.

Ching-Jung Chen, “Tea Parties in Early Georgian Conversation Pieces,” British Art Journal 10, no. 1 (2009): 30–39.

Woodruff D. Smith, “Complications of the Commonplace: Tea, Sugar, and Imperialism,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 23, no. 2 (1992): 277.

Carole Shammas, “The Domestic Environment in Early Modern England and America,” Journal of Social History 14, no. 1 (1980): 11–19.

Rose Kerr and Luisa E. Mengoni, Chinese Export Ceramics (London: V&A Publishing, 2011), p. 28. I am indebted to Angelika Kuettner of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for providing the information that correctly identified the ware.