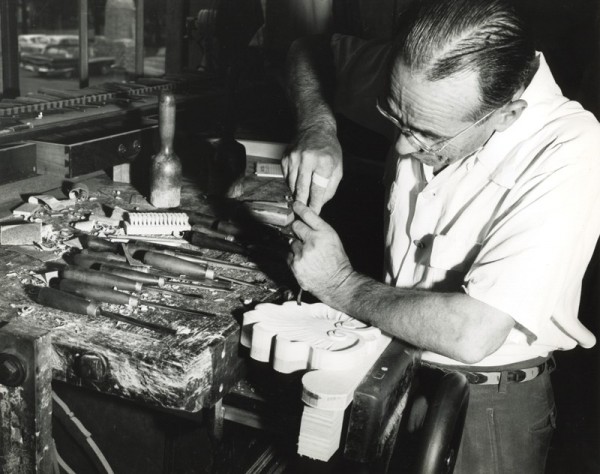

A Kaplan Furniture Company craftsman uses a gouge to carve details into an ornamental furniture feature, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1924. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

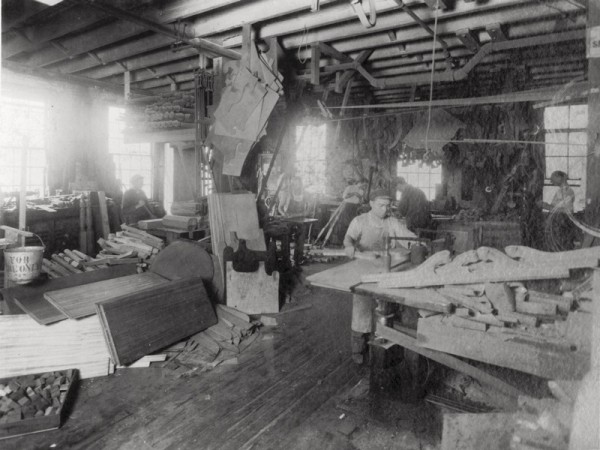

Isaac Kaplan surveys his workers inside his Osborne Street workshop, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1924. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Workers prepare components for several types of furniture, including pediments for bonnet top highboys, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1924. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

A craftsman in Kaplan’s workshop sands a Chippendale-style ribbon-back chair (also called a ladder-back chair with pierced rails), Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1924. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.) The unfinished quality of the chair demonstrates that this piece was in its early stages of preparation. It might then be taken to the carving department before being varnished.

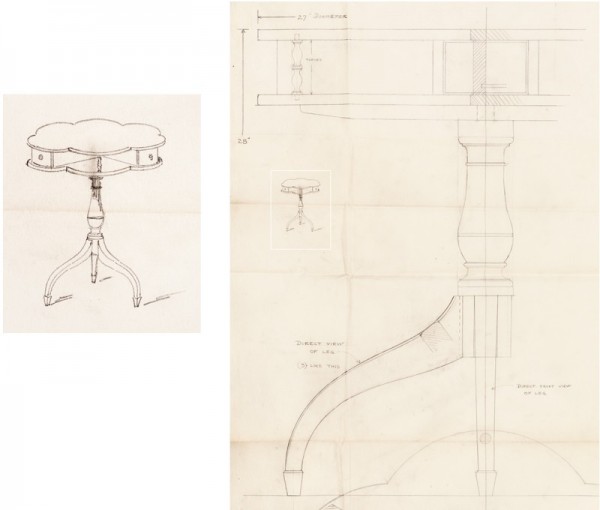

Blueprint for “Duncan” table, Kaplan Furniture Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1930–1940. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

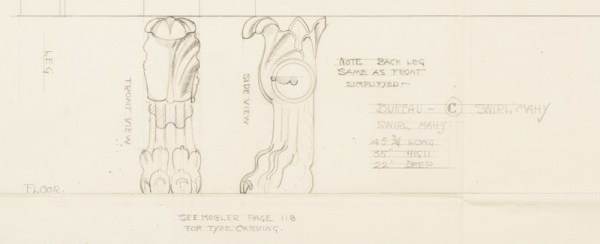

Detail of a blueprint for “Colchester” bureau, Kaplan Furniture Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1928–1940. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Promotional brochure for the Kaplan Furniture Company, 1926. (Courtesy, Cambridge Historical Commission.)

“The Bonnet Top Highboy” from Kaplan Colonial Line of Furniture. Promotional brochure, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1926. (Courtesy, Cambridge Historical Commission.)

Photograph showing Kaplan Furniture Company employees at Gore Place, Waltham, Massachusetts, c. 1930–1940. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Label for the Phillips Mahogany Double Bureau from the Beacon Hill Collection, Kaplan Furniture Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1930–1940. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Design for “Colchester Mirror,” Kaplan Furniture Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1928–1940. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Kaplan Furniture Company parade float, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1924. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Cover image for The Beacon Hill Collection of Early American Furniture (Cambridge, Mass.: Kaplan Furniture Company, c. 1930) (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

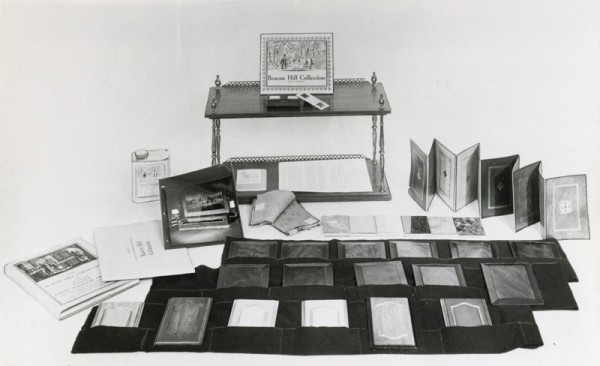

A Beacon Hill Furniture workshop kit, Cambridge, Massachusetts, February 9, 1955. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Display window for the Kaplan Furniture Company’s Beacon Hill Collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1930–1950. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Page from The Beacon Hill Collection as Interpreted by B. Altman & Company (Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, 1940), p. 181.

The “Beacon Hill Collection Showroom,” New York World’s Fair, New York, New York, 1939. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

Kaplan Furniture Company, promotional brochure, Cambridge, Massachusetts, c. 1950. (Courtesy, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.)

In 1920 Guy W. Currier came into possession of a chair presumably made by Thomas Chippendale. The chair’s provenance is lost to history; perhaps it was an inheritance, a legacy befitting Currier’s status as a member of the Massachusetts legislature and a fixture among America’s oldest fraternal organizations. Alternatively, Currier could have collected it, sharing in a recreation enjoyed by wealthy, patrician families up and down the East coast. In either case, instead of relegating his prized possession to a corner of his elegant mansion on Boston’s Beacon Hill, Currier commissioned copies to create a dining room set. Yet, who could imitate the singular craftsmanship of the much-lauded English cabinetmaker? Currier looked across the river to East Cambridge, already home to a number of men in the reproduction furniture industry. He decided to hire Isaac Kaplan, an Eastern European Jew who immigrated in 1904, and the founder of the Kaplan Furniture Company. By the time Currier contacted Kaplan, Kaplan ran a workshop with fellow craftsmen, the majority of them immigrants. His reputation was of a highly skilled cabinetmaker known for his ability to imitate the style of early American furniture.[1]

Currier felt safe entrusting his Chippendale chair to Kaplan, who showed all the proper respect due to both the object in question and the man who owned it. To Currier’s surprise, however, Kaplan completed the order for eight with eighteen chairs to spare. He deliberately sold the extras on the open market. Incensed, Currier sued Kaplan, viewing his act not only as theft of his property but a subversion of his relationship with the Jewish cabinetmaker. In his mind, his owning the original barred Kaplan from making copies of it. Despite coverage in the trade journal Furniture Manufacture and Artisan, the case never reached a resolution. Kaplan continued to manufacture chairs just like Currier’s for department stores and select clients into the 1960s.[2]

The conflict between Currier and Kaplan was not unusual among antique collectors and makers of reproduction furniture in the early twentieth century. Reproduction furniture occupied a highly visible yet polarizing role during the colonial revival, especially in heritage-oriented regions like New England. Well-known makers of historically accurate reproductions such as Nathan Margolis (1873–1925) operated out of workshops, producing a small-scale inventory and mainly working with individual clients in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. On the other end of the spectrum, firms like the Baltimore-based Potthast Brothers (fl.1892–1975) leveraged the appeal of the colonial revival to market products to a broad audience through a hybrid system of handcrafted and mechanized production. Despite these examples, historians of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century furniture frequently overlook reproductions. They are either absorbed into larger discussions of industrialized furniture manufacture or neglected in favor of the contemporaneous development of the Arts and Crafts style of craftsmanship. Moreover, the ambivalence among connoisseurs toward high-end reproductions may be due to the presence of fakes and forgeries among antiques. Even so, reproductions remain an intriguing subject for scholars of American decorative arts and material culture. If an object was crafted according to preindustrial methods and emulated an eighteenth-century British Atlantic style, how did it function as a product of the twentieth century?

Isaac Kaplan’s archival legacy provides clues to understanding how he and others in the reproduction furniture industry approached this complicated question. Kaplan combined an adherence to preindustrial forms with advances in mechanized manufacture to streamline production and deliver on contracts with major retail clients. Sold in department stores across the nation, his furniture paved the way for the saturation of colonial-revival style in middle-class American interiors throughout the early to mid-twentieth century. However, Kaplan’s motives were not purely commercial. By describing the maker of reproduction furniture as “the repository of good tradition,” Kaplan invoked a paradigm whereby colonial designs perpetuated American values, regardless of who produced them and how. This was particularly salient during the colonial revival, as consumers and collectors often expressed their preference for historically authentic furniture using nativist rhetoric. Among recent attempts to recover the participation and significance of ethnic and racial minorities in early American craftsmanship, the story of Isaac Kaplan demonstrates the unique role reproduction furniture and their makers played in continuing that tradition into the modern era.

The Rise of Reproductions

Born in Russia near the Lithuanian border between 1875 and 1880, Kaplan traveled to London as a young man with his wife to better their circumstances. He was trained as a cabinetmaker, but London was a competitive market and Jewish tradesmen frequently found themselves subject to antiforeign hostility. Across the Atlantic, America beckoned, and Kaplan joined the waves of Eastern European Jews making their way to the New World between 1880 and 1920. By the time of his arrival in 1904, Kaplan was just the latest addition in a long tradition of immigrant cabinetmakers who made a living reproducing historic furniture on commission and for the market. His predecessors included German-born Jewish cabinetmaker Ernest Hagen, who first gained notoriety in New York City in the 1840s, when he began reproducing furniture by master cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe through the firm Meier & Hagen. Other immigrants followed suit, notably the German Potthast brothers in Baltimore. In the same city, Italian immigrant Enrico Liberti (1884–1979) became the preeminent source for early American designs. In Hartford, the workshop of Nathan Margolis established itself as a source of elite reproductions, servicing both Jewish and Gentile clients in New England. Margolis’s employees, including Abraham Fineberg, Abraham Aronovsky, and Barney Rappaport, went on to establish their own cabinetmaking businesses. Many antiques dealers, such as Israel Sack and Wallace Nutting, also dabbled in the reproduction business and took advantage of their connections with collectors for private commissions. In Cambridge, Kaplan found that his own neighbors operated antique and reproduction shops: German-born William H. Zirkel and Scottish immigrant John Shaw worked only blocks away from Kaplan and helped make the city a center for colonial revival furniture production.[3]

Cambridge developed a reputation for furniture manufacture in the nineteenth century and was home to such companies as Irving & Casson–A.H. Davenport Co., Ferdinand Geldowsky & Company, and Braman, Shaw & Company. However, the majority of these businesses closed their doors within the first couple of decades of the twentieth century. While they previously churned out passable machine-made copies of early American furniture, the taste for handcrafted furniture soon began to spread. Thanks in part to the antiquarian fervor sparked by the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, along with the installation of period rooms at historical sites and museums, many Americans began to view historically accurate craftsmanship as a significant evaluator for furniture. As the Cambridge Chronicle observed in 1889, “A few years ago Eastlake furniture was all the rage. The fashion has now strongly set toward Chippendale designs, and for some years to come they will be the most popular.” This preference for preindustrial forms influenced the businesses of many immigrants with skill in cabinetmaking, easing their transition into the reproduction furniture business.[4]

Kaplan arrived in Cambridge just before the peak of the colonial-revival period and found himself able to imitate the hand-carved “Chippendale” pieces so widely praised. Taking advantage of these changing consumer demands, he began marketing himself as a “late from London” authority in the early American style. From then on, Kaplan’s early career reads like a Cinderella story. In 1905 he took a job under Alex Grant at the A.M. Furniture Company in Cambridge, and soon after moved on to become an “all around man” at the nearby Paine Furniture Company. Despite being handicapped by his lack of fluency in reading and speaking English, Kaplan’s natural skill prevailed, as did his entrepreneurial instinct. After a few years working for Paine, Kaplan decided to strike out on his own. It is also rumored that he constructed a tilt-top table as a sample for one of his superiors at Paine’s, who admired it enough to encourage Kaplan to open his own business. Another source reports that Kaplan got his start after taking on a private commission for a “wealthy old Beacon Hills dowager” by creating a table indistinguishable from her original. Whatever the truth, his cabinetmaking skill became his brand, which dominated the marketing of his furniture long after his workshop became mostly mechanized.[5]

Kaplan planned to grow his company from the outset, and his first step was getting the capital necessary to invest in modern machinery and a skilled workforce. Beginning in a rear room on Osborne Street, Kaplan received a loan of $100 from the Harvard Trust Company. He used the money to construct the tilt-top tea table that netted him his first commission. A buyer with the Jordan Marsh Company reportedly paid Kaplan $6 for his work on delivery, which was enough to purchase a supply of materials to produce another tea table on speculation. The work spoke for itself, and Marsh placed a large enough order to necessitate Kaplan’s hiring of a helper, Eastern European immigrant Valenti Jaworski.[6]

By 1911 Kaplan had amassed enough capital to register his business I. Kaplan Company, which was valued at $5,000. Fellow immigrant Jacob Charak, founder of the Old Colony Furniture line of reproductions, joined him in business in 1915 after contributing $1,500 in capital. In 1919 Kaplan bought out Charak and renamed his solo business the Kaplan Furniture Company. He immediately registered the trademark Kaplan Colonial Line of Reproduction Furniture (shortened to the K-C Line) and began expanding and diversifying his inventory. As one contemporaneous profile of him exclaimed, “Mr. Kaplan’s work is highly artistic, so much so, in fact as to win the cordial approval of those who are well-versed in all that pertains to the various patterns of the antique and colonial styles of furniture.” Kaplan drew attention to his business by alluding to his social connections among elite collectors and connoisseurs, although his ill-fated encounter with Guy Currier would come at the end of his specialty commission work.[7]

The colonial revival provided a legitimate and lucrative opportunity for immigrant cabinetmakers like Kaplan to become entrepreneurs and avoid industrial factory labor. Like many other collectors, dealers, and makers of the era, Kaplan applied a catchall “colonial” brand to any furniture style from the mid-seventeenth to the early nineteenth century. For him, the term evoked a nostalgic image of preindustrial manufacture that appealed to consumers. Kaplan translated the allure of historic furniture into commodities affordable to an upwardly mobile middle-class American family. While a workshop like Margolis’s remained dedicated to handcraftsmanship, the Kaplan Furniture Company employed a hybrid system of machine manufacture and hand-carving, relying on a tier of skilled cabinetmakers to handle detailed ornament. Photographs taken in 1924 at the behest of Kaplan illustrate how his business expanded to supply custom batch orders for the retail market and moved away from the earlier model of specialty commissions for clients (figs. 1-4). These images demonstrate a density of inventory, ample storage capacity, sophisticated industrial machinery, and a large workforce diverse enough to accommodate up to seventeen different production processes, including cutting and carving pieces, assembly, detail work, varnishing, sanding, painting, and upholstery. In his factory, Kaplan’s employees produced multiples of component parts of furniture, such as legs and drawers, and assembled them in a different section of the warehouse. While carving, inlaying, and leather tooling were done by hand, modern machinery expedited production. A photograph of a worker standing at an unfinished ribbon-back chair demonstrates how industrial saws cut wood—possibly oak or white pine—for the frame, legs, stiles, while mechanized planing tools shaped the narrow cabriole legs and curved horizontal rails for the back (fig. 4). It is likely that a less-skilled worker assembled dozens of pieces in this rough form before sending them to a different department, where a specialist in carving added detail to features like crest rails (see fig. 1). From there, the chair was sent to another craftsman who applied the finish and then to the upholstery department. This type of compartmentalization and specialization was more akin to production in large eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century furniture-making shops than the assembly-line manufacture pioneered by Henry Ford. Specialized batch production was typical in higher-end reproduction workshops.[8]

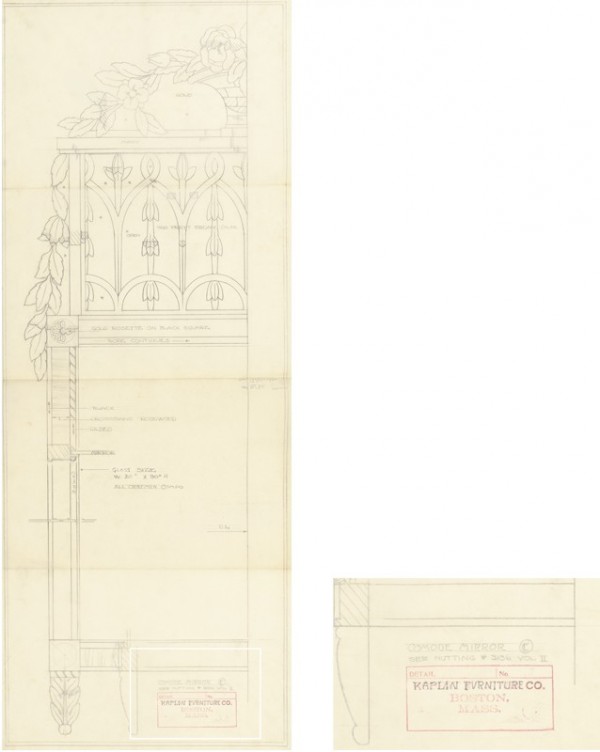

Manufacturers of reproduction furniture, particularly those who staked their reputation on creating quality imitations, distinguished themselves through their adept manipulation of brand transparency. Just as nebulous as the term “colonial” was for reproduction styles, “authentic” reproductions meant anything from looking handcrafted (or in the genre of folk art) to the artful copies of highly desirable antiques. According to one advertisement, Kaplan’s commercial pieces appeared “practically indistinguishable from the rare hand-carved originals imported from England before the Revolution.” Despite the upgrade of his supply process to meet the demands of his clients, Kaplan took great pains to stress his company’s standards of craft integrity, authenticity, and masterful execution. In his workshop, machines planed, carved, and embossed multiples of the same forms, but Kaplan’s craftsmen used traditional hand skills to refine machine-generated components. Another advertisement in 1926 boasted, “When completed, each piece in the Beacon Hill Collection reflects the skill of many specialists; men who have mastered hand carving, fitting of drawers, and doors, lathe turning, hand-joining, and hand-finishing.” These processes were likely specialized, but constituted only a small percentage of the entire object, the majority of which was machine-produced. For example, in the directions included for the designs of an undated “Duncan” table in the Kaplan Furniture Company archives, Kaplan instructed his workers to hand-turn a piece of wood that acted to either tenon or peg the two slabs of wood comprising the table top and bottom, allowing for the installation of drawers between them (fig. 5). The resulting product emulated an early nineteenth-century Duncan Phyfe card table, possibly lifted from a photograph in Frances Clary Morse’s 1917 edition of Furniture of the Olden Time. All other aspects of the table, including its pedestal base, legs, and spade feet, were likely manufactured by machine. Similarly, in his designs for a “Colchester” mahogany bureau, the instructions refer to carving only for the claw feet, which are drawn in elaborate detail (fig. 6). Nonetheless, it was these details, along with expensive woods like mahogany, that discerning buyers noticed.[9]

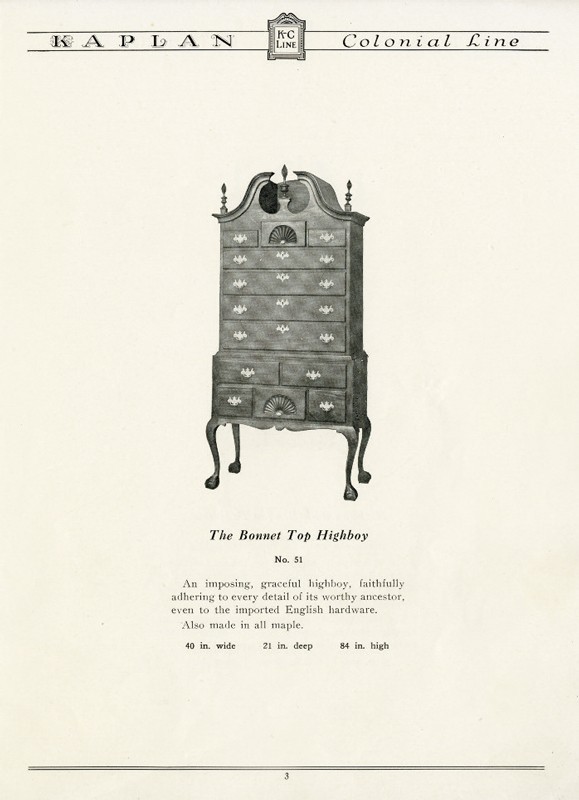

Under Kaplan’s guidance, his company began a promotional campaign targeting various high-end department stores. One brochure from the 1920s sent to the Thomasville Chair Company in North Carolina depicted a clipping of a fabricated New York Times article detailing a recent sale of New England antiques (fig. 7). This alleged sale fetched more than $35,000 and included eighteenth-century maple furniture in the English “Hepplewhite” and “Sheraton” styles, six Duncan Phyfe–style side chairs, and mahogany and gilt mirrors. Next to this, Kaplan guaranteed his products were not “crude in design and poor of construction,” but proudly stood the test of time as quality merchandise alongside these fine antiques. An image of Kaplan’s “Bonnet Top High Boy,” with classic Newport-style rococo ornament and carved finials covered the back of the brochure (fig. 8). Kaplan promised it “[faithfully adhered] to every detail of its worthy ancestor, even to the imported English hardware.” Kaplan’s promotions worked their magic on numerous retailers on the East Coast, including the prestigious B. Altman & Company in New York City. In determining what to order from Kaplan, department store buyers had a selection of more than two hundred conventional options ranging in price from an $18 bench to a $220 highboy. Higher-end pieces were made of mahogany, had imported hardware, and hand-worked features. These pieces also came in varnishes called “Colonial Red,” “Antique,” and “Sheraton Brown.” The Kaplan Furniture Company archive includes over five hundred blueprints of designs made between 1920 and 1972. Although the company adapted Asian-inspired furniture elements toward midcentury, and even began producing radio cabinets, the designs for furniture made in the 1920s and 1930s are given early American antique–related names. For example, there are five “Sheraton” pieces, including a commode and a sofa, fifteen “Chippendale” pieces, and three “Adam” pieces. Other furniture styles were named for New England towns, such as Copley, Colchester, Burlington, Weston, and Portsmouth. Thus, the Kaplan Colonial Line not only emulated the look of antiques but conveyed the same rich associations through branding.[10]

By the end of the 1920s Kaplan’s commercial success prompted him to expand his business. Having started in the back room of 60 Osborne Street, Kaplan was able to purchase the entire city block for $250,000 in 1927. One writer in the trade journal Furniture Manufacturer remarked, “few stories in Greater Boston business romance are more interesting than Mr. Kaplan’s, few better illustrate the opportunities which are open to one who has the dogged determination and ability to take advantage of them.” By moving away from singular handcrafted commissions to embrace wholesale, industrialized production, Kaplan’s business reflected the growing democratization of the colonial revival among consumers.[11]

The All-American Craftsman

Reproduction antique furniture complicated the notion of the traditional American craftsman. To promote his business, Kaplan played on nostalgia, conjuring up an image of an old New Englander turning and carving a chair by hand in his workshop. In reality, Kaplan’s workforce incorporated sophisticated machinery and had the space to manufacture a large inventory. Moreover, his company also reflected an ethnic and racial dimension to colonial revival production—a feature many at the forefront of the movement made invisible. Along with other Eastern European Jews, Kaplan hired Italian and Portuguese immigrants and African Americans. How they felt about making reproductions of furniture by Sheraton, Chippendale, and the Seymours is uncertain, as few records reveal their attitudes. However, their loyalty is unquestioned: the average craftsman worked for Kaplan for approximately twenty years, and his assistant Billy Weinstein remained with him for twenty-five years.[12]

Kaplan saw his business not solely as a commercial enterprise; there was a social dimension in the ability to create furniture, and particularly learning the cabinetmaking trade. In his introduction to a catalogue of reproduction New England furniture, he stated, “The maker of good furniture is both artist and craftsman; he is the repository of good tradition, and he has the skill to preserve and continue it.” His rhetoric dovetailed with a developing pedagogical emphasis on colonial forms within the industrial arts in the 1920s and 1930s. While the majority of his workers previously trained in some aspect of cabinetmaking before immigrating to the United States, Kaplan also employed second- and third-generation immigrants who had learned cabinetmaking in major American cities. Kaplan reportedly took in forty-four boys from the Boston Trade School in 1940 alone. In that school’s program, much of the vocational training related to understanding preindustrial forms and promoting them as instructive to study. Educator Frederick Love identified these historic styles as the best for students to reproduce because they enabled them to practice such traditional techniques as turning. Andrew Roswall, head of the Boston Trade School, affirmed this statement in 1920, highlighting student work that included reproduction Chippendale tables, colonial mahogany writing desks, and inlaid, satinwood sewing stands. As the makers of these reproductions, Kaplan’s workers absorbed the principles and significance of early American furniture, even if they could not afford the products themselves. However, making reproductions for reputable companies paid off: Kaplan compensated his workers with fair salaries, a twice-a-year bonus, generous vacations, and options for purchasing shares in the company.[13]

Kaplan was not the only one to see the social value of making early American reproductions. Outside Kaplan’s factory, colonial revival cabinetmakers leveraged their skill to access exclusive spheres of society. The career of Paul V. Smith, an African American furniture maker in Lexington, Kentucky, provides a case in point. Smith serviced a mostly white Southern clientele, and his handcrafted reproductions of the usual master cabinetmakers resided in “aristocratic residences” up and down the coast. Smith also taught at the Dunbar trade school, instructing young black men in the art of historical furniture. According to a profile in the African American magazine The Crisis, “Mr. Smith’s pupils also repair and restore fine old antiques for a growing number of delighted patrons and collectors.” In this instance, the skill and masterful reputation of the reproduction cabinetmaker appeared to elevate his stature. Working within the colonial revival granted Smith and his apprentices some measure of economic and social mobility during a time when African Americans were denied basic civil rights.[14]

Similarly, Eastern and Southern European immigrants making reproductions received commissions to furnish civic interiors. Enrico Liberti made more than twenty-two chairs and other assorted pieces in the eighteenth-century style for the Old Senate Chamber in the Maryland State House. In Hartford, Nathan Margolis restored and made furniture for the Connecticut State House. Meanwhile, antiques dealer and sometime cabinetmaker Israel Sack collaborated with Henry Ford (who was known to hold anti-Semitic views) to furnish the historic Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts, in 1923. Kaplan did not fulfill commissions such as these after his company began producing for retail; while furniture from his assorted lines continues to circulate on the secondhand market, it is unknown if his work is accessioned in a historic institution. However, Kaplan and his men looked to such sites as inspiration, evidenced by a photo taken outside Gore Place in Waltham, Massachusetts (fig. 9). As the label illustrated in figure 10 indicates, Kaplan consistently invoked the antiquarian and patrician ideals these places conjured in the minds of the thousands of tourists who visited historic New England sites every year.[15]

Kaplan also looked to “authorities” on all things colonial: the connoisseurs, collectors, and antiquarians who frequently published encyclopedic surveys of early American furniture. A particular source of inspiration was Wallace Nutting, credited with helping to make reproduction antiques known to middle-class Americans through several lines of furniture, including the “Correct Windsor Furniture” line in 1918. As decorative arts scholar Thomas Denenberg notes, Nutting’s real innovation was the cross-marketing of his furniture with the highly curated image of early Americana made popular by his photography. Depicting staged interiors evoking the “Pilgrim days” of American history, Nutting branded his furniture with similar historically fictitious connotations.[16]

Nutting frequently employed Morris Schwartz of Hartford, Connecticut, to restore furniture before he attempted to sell it. Schwartz, another Jewish immigrant, worked on colonial pieces for private clients and museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. One piece in particular was a late eighteenth-century mirror with fretwork and gilded rosettes that Nutting sold to a collector and published in his influential Furniture Treasury—citing Schwartz in the caption. Kaplan’s use of Nutting’s book as a design source is revealed in the former’s version of that mirror, the “Colchester Mirror,” which included expensive materials like gold, mahogany, ebony, and rosewood (fig. 11). Kaplan instructed his workers to re-create the gold rosettes, gilding the piece according to the classicizing style of the period.[17]

Unlike Kaplan, Nutting’s interests solidly aligned with those who viewed the colonial revival as a mission to reclaim America’s past for white Americans. He even promoted his homespun constructions as remedies for those “beset by alien faces and language.” This was ironic for a man who relied on immigrant workers. For Isaac Kaplan, appealing to a wider and more diverse demographic was a key component in his marketing. Immigrant families, many of whom assimilated into a suburban middle class, also purchased historic reproductions to decorate their homes. Kaplan’s furniture catalogue frequently included informative sections about “Great Designers,” such as Thomas Chippendale or Robert Adam, and identified differences in historic styles. Essentially, he was teaching his readers to appreciate and understand early American furniture, in the hopes that they would choose his products for both their aesthetic appeal and didactic function. Furthermore, Kaplan’s pieces were “honest” reproductions made of good materials by competent craftsmen. He did not see himself as marketing affordable furniture but, instead, “rare heirlooms of colonial wealth at prices within reach of many thousands with less extensive means.” He tied his products to the antiques his customers encountered in museum period rooms, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, which opened in 1924. The original intent of those period rooms was to foster civic education and “Americanize” visitors, including immigrants.[18]

The appeal of Kaplan’s collection was that it looked as if it belonged in a museum, like any other antique. Therefore, owning a Kaplan reproduction would serve to express the cultural values projected on early American decorative arts. In fact, one edition of a later catalogue proclaimed that his line of furniture was the product of skilled handwork, “designed for those who desire authentic reproductions and the museum type of piece without concessions to mass production.” Kaplan’s men produced these pieces in large quantities, enough to supply approximately forty department stores across America. Yet the handcrafted appearance of Kaplan’s objects endured, and that aspect spoke to consumers who sought a level of cultural nationalism and social aspiration in their interiors.[19]

While the lack of acknowledgment from the museum community might cast Kaplan’s products in a subtier of high-end reproduction furniture, his brand remained in stores far after the colonial revival peaked in the 1920s and 1930s. This had to do with Kaplan’s ability to maintain consistency of quality in his factory while shrewdly promoting his furniture to a wider income bracket. In Cambridge, Kaplan was regarded as a leading member of the community, and his business participated in elaborate displays of communal patriotism. During an Independence Day parade in 1924, Kaplan and his workers drove a company car festooned with flags and outfitted with examples of his furniture (fig. 12). Atop the vehicle was a platform on which rode one of Kaplan’s men constructing a piece, going about his business as the float drove down the streets of Cambridge. This display was meant not just to aggrandize Kaplan’s business but served to raise the value of both reproductions and the men who made them. If a colonial reproduction made by an immigrant could belong in a government space, or even the “all-American” domestic interior, then Kaplan and his men could rightfully claim an all-American status for themselves.[20]

Authenticity and Artifice

Kaplan’s business continued to expand in the 1930s, and his commercial efforts resulted in lucrative partnerships with department stores across America. In her overview of Massachusetts industries in 1930, Orra Stone echoed her contemporaries when she called Kaplan’s success a bit of a fairy tale. From an immigrant with twelve cents to his name setting up shop in 1907, to “the leading specialist in the manufacture of colonial reproductions,” the Kaplan Furniture Company was now a household name in the industry. Keeping up with the times, Kaplan took the marketing of his products a step further with an ambitious but incredibly popular line of furniture called the Beacon Hill Collection. The significance of this collection lay not in its formal or material presentation, but in its association with the elite historical neighborhood of the same name.[21]

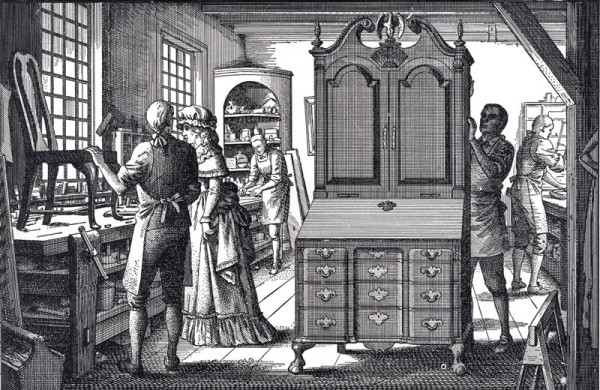

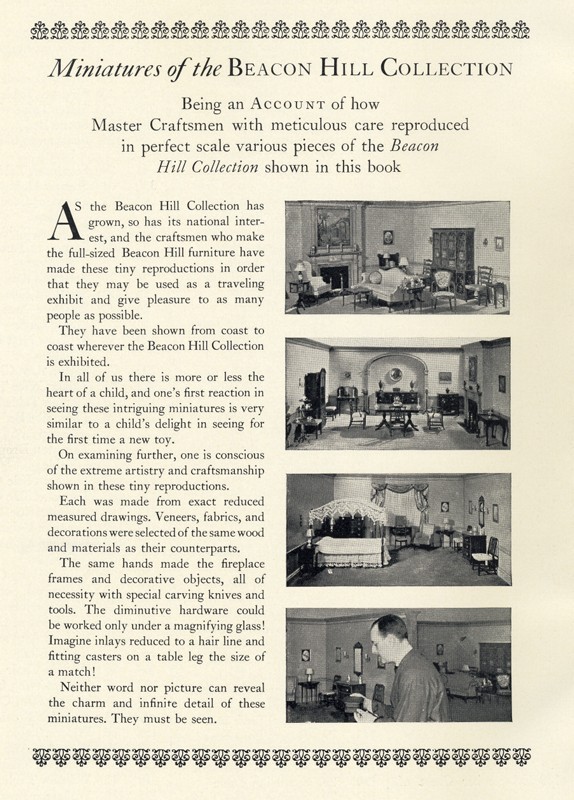

Kaplan began his Beacon Hill Collection in 1930, taking its name and source material from the very homes he frequented in his early days of private commissions. Almost fifteen years after his incident with Guy W. Currier, Kaplan returned to the proverbial scene of the crime (although not Currier’s home in particular) to reproduce once more the singular antiques and interiors found within. Kaplan and his men studied these homes and re-created the best examples of early American antiques, illustrated in the pages of his Beacon Hill Collection catalogue. At approximately 200 pages, it circulated around department stores and was free with a purchase from that collection. Reprinted multiple times between the 1930s and 1960s, The Beacon Hill Collection was illustrated with photos of elaborately staged eighteenth-century interiors featuring Kaplan’s furniture, a primer on early American decorative arts, and a walking tour of the neighborhood with historically significant stops. The cover of The Beacon Hill Collection communicated his sentimental attitudes regarding the craftsmen of a preindustrial age, showcasing an image of a workshop and busy cabinetmaker (fig. 13). As with most visual culture related to the colonial revival, this was an imagined scene, drawn for the First National Bank of Boston in the 1930s and lent to Kaplan for the purposes of reproduction.

The Beacon Hill Collection catalogue was more than a price guide; it was an exquisitely produced photo book savored by anyone with an appreciation for historical interiors. With each turn of the page, readers found themselves guided through exclusive spaces reminiscent of those on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reinforcing this association were the lavish department store displays for the Beacon Hill Collection. Traveling salesmen for the company carried kits that included the catalogue, wood samples, and a viewfinder to visualize the mock-up showrooms. These displays cost roughly $1,368 for department stores to buy from the company, and included fabric, fourteen pieces of related home furnishings, and “scenic” materials for a sixteen-square-foot setting (fig. 14). Confronted with the physical space, one could not help but think the department store doubled as a gallery.[22]

Kaplan’s colonial reproductions were not works of art, but their presentation was accorded all the care and attention paid to something artistically valuable. Moreover, the photographs inside the catalogue, along with the showrooms, provided an instructional model for arranging one’s own home with Kaplan’s products and encouraged customers to purchase the complete look (fig. 15). As Kaplan’s company continued to produce in larger quantities, the line between artifice and authenticity blurred. This understandably provoked the irritation of his contemporaries who produced specialty reproductions. As Nathan’s son, Harold Margolis, put it in an oral interview:

Well, there’s always competition, but I have always said and felt not in the quality of our work. Of course, there are many factories in New York that expanded to large volumes with shows in New York and elsewhere like if you know the cabinet furniture, which made Beacon Hill furniture and Old Colony and several others. Now, they made Colonial furniture in large quantities. They kept to the forms of the old pieces but went into machine dowels, machine dovetailing, I meant to say, and dowel construction and a great deal of the work was hand-carved, but they produced this in such quantity that they were able to list price them to give dealers and decorators discounts. Well, people that didn’t know would feel that it was just as good as Margolis for less money, but we know it wasn’t so.

Margolis pointed to Kaplan’s factory process as inhibiting his furniture’s quality, and there certainly was a world of a difference between a chair made in the so-called Chippendale style by Margolis and the wholesale production of similar chairs for the department store. However, Kaplan’s story illustrates how the idea of historical authenticity became an asset in his branding. In his mind, heritage was never out of fashion.[23]

Branding was more crucial to sustaining Kaplan’s business. The Beacon Hill name invited consumers into a world of republican refinement. Name recognition appealed to retailers as well, and by the late 1930s Kaplan began lending out the Beacon Hill Collection brand to established stores throughout the country. In exchange for a secure and exclusive use of the name, the retailer would expend substantial effort and considerable expense promoting it. Kaplan leveraged the cachet of the Beacon Hill Collection at little cost to himself, understanding that the marketing apparatus of the department store was more strategically viable in the long term than his own efforts. Thus, throughout the next several decades the Beacon Hill Collection overtook Kaplan Furniture Company as the main brand used in transactions with retailers. His clients sometimes exploited this partnership, marketing the collection as being manufactured in-house. In each consecutive edition of the catalogue, a different department store took credit for the line, but the images remained the same. Kaplan continued to receive compensation, and his business flourished. By the late 1940s the Beacon Hill Collection had showrooms in sixteen department stores spread across the United States, and more than thirty sold his furniture on the main floor.[24]

The commercial success of the Beacon Hill collection was due mainly to clever marketing and Kaplan’s acute understanding of what his consumers wanted from their high-end colonial reproductions. His period-room department-store displays satisfied a certain faction of his ideal demographic, but Kaplan also wanted to draw people to the Beacon Hill Collection by making it a novelty attraction. Reminiscent of his patriotic parade float capturing the attention of Cambridge, Kaplan took advantage of the colonial revival’s culture of spectacle to market his products with an exhibition of Beacon Hill Collection miniatures.

First constructed by Kaplan and his son Simon circa 1937 to model the antiques they observed in the Beacon Hill neighborhood, these miniature reproductions were 1/64th scale versions of Kaplan’s originals made in his factory using dental tools. Exquisite and uncanny in their craftsmanship and accuracy of design, the interiors illustrated within the pages of The Beacon Hill Collection catalogue were in fact made up of these miniatures—to the surprise and delight of many (fig. 16). They cleverly and effectively demonstrated the skill of Kaplan’s employees, especially as later editions of the catalogues provided images of these miniatures being made. One department store arranged the miniatures alongside the showroom, and the tiny pieces proved so popular with the public that a traveling exhibition was formed to circulate them among department stores. To top it all off, the Beacon Hill Collection miniatures had a spot at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York (fig. 17). Exposure on this scale enabled Kaplan and his products to retain name-brand recognition while formally exhibiting the skill of the workers. The evolution of the Beacon Hill Collection into a high-end but still relatively affordable line of furniture reflected the full commercial saturation of the colonial revival.[25]

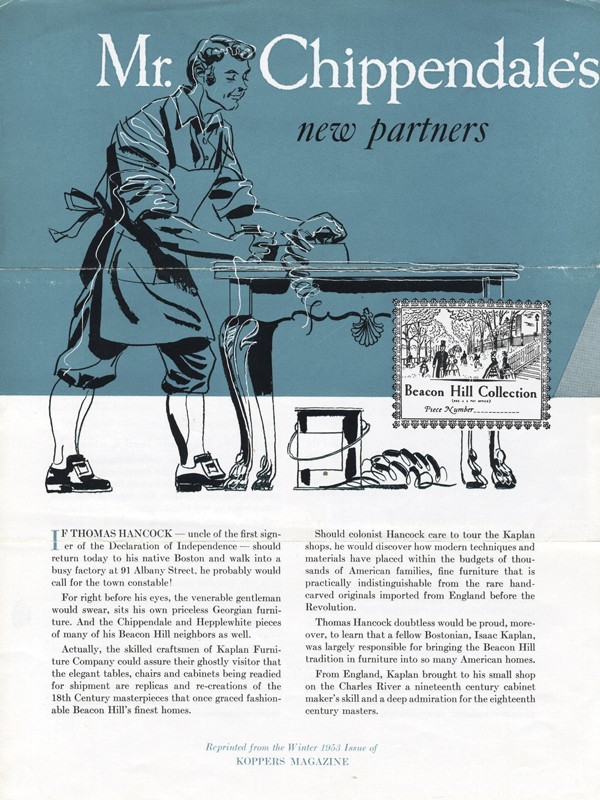

From its days as a small workshop in Cambridge to a large-scale business based in Medford, Massachusetts, the Kaplan Furniture Company branded itself as a beacon of style, quality, and authenticity. Through the 1950s reproduction antiques waxed and waned in their popularity but still played a role in how people presented themselves and their homes as American. Additionally, the colonial revival remained a reflection of society’s aspirations and anxieties toward culture, identity, and patriotism. One advertisement from the 1950s imagined American icon John Hancock visiting the Kaplan Furniture Company. Looking around and seeing the furniture of his era, Hancock is shocked to find they are machine-made and modern. The following passage stated, “Should colonist Hancock care to tour the Kaplan shops . . . the skilled craftsmen of Kaplan Furniture Company would assure their ghostly visitor that the elegant tables, chairs and cabinets being readied for shipment are replicas and re-creations of the 18th century masterpieces that once graced fashionable Beacon Hill homes.” By the time this advertisement circulated, Isaac Kaplan’s central role in the company had passed to his sons, Leon and Simon, and his grandson David. Kaplan continued to supervise his company as it segued to focus more on interior design in the 1960s. He also acquired smaller companies. For example, in 1959 he bought his former partner Jacob Charak’s Old Colony Furniture. By then, the colonial revival was in decline and new trends in furniture design took hold of the marketplace. Yet the Beacon Hill Collection remained in department stores, even after Isaac Kaplan died in 1962. The company lasted for nearly a decade more before it was liquidated in 1972. Leon and David Kaplan continued to market reproductions to the trade afterward.[26]

During Isaac Kaplan’s early life and business, he claimed several titles, including cabinetmaker, salesman, and company president. Correspondingly, his objects circulated through a number of different spheres, from the socially elite interiors of Beacon Hill to the ethnically diverse homes of America’s middle class. Colonial revival reproductions were multivalent artifacts, able to transform and take on new meaning in any environment. They affirmed the racial and economic status of white consumers, while simultaneously bolstering the social and civic legitimacy of immigrants. Furthermore, by describing the maker of reproduction furniture as “the repository of good tradition,” Isaac Kaplan demonstrated that men just like him upheld the values that made America great. In one advertisement, Kaplan went so far as to refer to his workers as “Mr. Chippendale’s New Partners” (fig. 18). As the figurative inheritor of this important furniture legacy, Kaplan framed his colonial reproductions as the antiques of tomorrow. Today, as these objects approach the hundred-year mark, when they will become genuine antiques, it appears they might live up to Kaplan’s promise.

Guy W. Currier (1867-1930) was a member of the Bethany Commandery of Knights Templar and the New Algonquin Club of Boston, and served on a committee on judiciary in the House of Representatives in 1899. A Souvenir of Massachusetts Legislators (Brockton, Mass.: A. M. Bridgman, 1900), 9: 136.

“Suit over Chippendale Chairs,” Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan (March 1920): 150.

The cabinetmaking industry in London was competitive throughout the late nineteenth century, as like-minded Polish and Russian Jews worked longer hours and for lower wages, earning the hostility of local tradesmen. Leonard D. Smith, “Greeners and Sweaters: Jewish Immigration and the Cabinet-Making Trade in East London, 1880–1914,” Jewish Historical Studies 39 (2004): 111. One source credits Kaplan as living in Warsaw and St. Petersburg for four years before coming to the United States. David Kaplan, e-mail interview by the author, April 2016; Dan P. Rossiter, “Magic Rise of Kaplan: Or How Immigrant with a Capital of 12 Cents Founded Furniture Manufacturing Company Which Has Enjoyed Phenomenal Growth,” Furniture Manufacturer (July 1928): 60–61. During the wave of immigration from 1880 to 1914, one of the largest in the nation’s history, the immigrant population of Boston nearly tripled. Many left Europe owing to dire circumstances, including the Pale of Settlement that imposed harsh restrictions on Jewish movement and economic activity under Russian rule. For brevity, the focus of this paper will remain in the Boston-Cambridge area. The subject of immigrants arriving in Boston in the late nineteenth century is described in Thomas Archdeacon, Becoming American: An Ethnic History (New York: Free Press, 1983); and Barbara Miler Solomon, Ancestors and Immigrants: A Changing New England Tradition (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1956). Robert A. Rockaway, “The Industrial Removal Office and the Dispersal of Eastern European Jewish Immigrants in the United States,” in Michael: On the History of the Jews in the Diaspora (2000): 133. Earnest Hagen, “Personal Experiences of an Old New York Cabinet Maker,” R. T. H. Halsey Papers, published in Elizabeth A. Ingerman, “Personal Experiences of an Old New York Cabinet Maker,” Antiques 84 (November 1963): 576-80. For detailed biographies of these men and their businesses, see Rebecca E. Phillips, “Almost History: American Colonial Revival Furniture and the Career of Enrico Liberti (1894–1979)” master’s thesis, University of Delaware, 2007; Catherine Rogers Arthur, “‘The True Antiques of Tomorrow’: Furniture by the Potthast Brothers of Baltimore, 1892–1975,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2000), pp. 31-58; and Eileen S. Pollack, “Furnishing Community: The Role of Margolis Furniture in the Lives of Hartford’s Gentile and Jewish Families, 1920–1970” master’s thesis, Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum and Parsons School of Design, 2004. Briann G. Greenfield, Out of the Attic: Inventing Antiques in Twentieth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), p. 88.

For more information, see Victor S. Clark, History of Manufactures in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1916), 3: 244; Ann Gilkerson, “Furniture Manufacturing in East Cambridge, 1851–1916,” 1982, Cambridge Historical Commission, Cambridge, Mass.; Jan Seidler, “The Furniture Industry in Victorian Boston,” Nineteenth Century 3, no. 2 (Summer 1977): 65–69; “A. H. Davenport and Company, 1880–1908,” in Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, “Dictionary of Architects, Artisans, Artists, and Manufacturers,” in In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement, edited by Doreen Bolger Burke (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986), p. 418. “Old Cambridge,” Cambridge Chronicle, October 26, 1889, p. 5.

“Firms That Help Make Cambridge Famous,” Cambridge Chronicle, May 6, 1911, p. 42. Rossiter, “Magic Rise of Kaplan,” p. 60. Alan Rosemary Gale, “Leaders in the Industry,” Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan (April 15, 1940): 1. David Kaplan, e-mail interview by the author, April 2016

According to local historian Orra L. Stone, “Lacking even a penny of insurance, the founder of the company saw his original little Osborne Street factory go up in smoke within three weeks after he located there, in 1907, but President W. A. Bullard, of the Harvard Trust Company, had become so impressed with Kaplan’s ability and ambition that he promptly loaned him $100 to start over again, and today the beneficiary of that meager capital is one of the trust company’s largest depositors.” This account cannot be verified, so we must treat it as dubious, though it is often repeated in extant reports on the origins of Kaplan’s business. Orra L. Stone, History of Massachusetts Industries: Their Inception, Growth, and Success, 4 vol. (Boston: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1930), 4: 20. Rossiter, “Magic Rise of Kaplan,” p. 61.

“New Massachusetts Corporations,” Cambridge Tribune, July 15, 1911, p. 8. For more on Charak, see Alan Rosemary Gale, “Leaders in the Industry,” Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan (April 15, 1940): 51. “Kaplan Furniture Company Succeeds Kaplan-Charak Company,” Furniture World, no. 1280 (December 4, 1919): 38. “Firms That Help Make Cambridge Famous.”

There were some, like Roger Bemis, writing for the American Architect in 1923, who cautioned against the overuse of the word “colonial” as it applied to antiques: “The word ‘colonial’ has been done to death. Strictly speaking, nothing made after the Declaration of Independence can be called Colonial, yet the name is applied to thousands of refined, carved and spindly objects which came later, of William and Mary, Hepplewhite, Sheraton, and Chippendale derivation, whereas the Pilgrim furniture, so utterly dissimilar, is essentially Colonial and American.” Bemis, “Department of Architectural Decoration and Furniture: Seventeenth Century Interiors and Furniture in United States,” American Architect and the Architectural Review (1921–1924) (June 6, 1923): 525. My use of the term “nostalgic” owes much to the larger explorations on American culture from 1880 to 1940 by Fred Davis, Miles Orvell, and Michael Kammen. Kammen, American Culture, American Tastes: Social Change and the 20th Century (New York: Basic Books, 2000); Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); and Davis, Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia (New York: Free Press, 1979). Machinery had been a fixture of the reproduction furniture business since the mid-nineteenth century. New York cabinetmaker Ernest Hagen remembered that while employed at Bass Cabinet Makers in the late 1840s, “the work was all done by hand, but the scroll sawing of course was done at the nearest sawmill.” Quoted from Ingerman, “Personal Experiences of an Old New York Cabinetmaker.” Additionally, Michael J. Ettema identified quantity, not quality, as the inherent deficiency in the nineteenth-century furniture industry, and this was due in large part to mechanized manufacture and increasingly alienated labor, wherein the object itself was comprehended as disembodied parts. Ettema uses the phrase “proliferation, not elaboration” in his discussion of the legacy of technological innovation in the nineteenth-century furniture industry. Ettema, “Technological Innovation and Design Economics in Furniture Manufacture,” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (Summer/Fall 1991): 198.

An example of this semantic malleability can be found at Colonial Williamsburg. Charles Alan Watkins, “The Tea Table’s Tale: Authenticity and Colonial Williamsburg’s Early Furniture Reproduction Program,” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 21, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2014): 155–91. Kaplan Furniture Company advertisement, Koppers Magazine (Winter 1953): col. 805, Joseph Downs Collection of Manucripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum & Library. Kaplan likely lifted the design of the “Duncan” table from the Duncan Phyfe card table (c.1810-1820) in Frances Clary Morse, Furniture of the Olden Time (New York: Macmillan Company, 1917), illus. 277. In the blueprint for the “Duncan” table (fig. 5) Kaplan’s designers made a note to look to “Mobler, Page 118” for the type of carving they wished to emulate, perhaps referring to Danish furniture manufacture. The exact reference is unknown.

Promotional brochure for Kaplan Furniture Co. (1926), Cambridge Industry and Business-Catalogs (1878–1958), Cambridge Historical Commission, Cambridge, Mass. Kaplan Furniture Company, Price Guide to the K-C Line of Colonial Furniture (1926), Cambridge Industry and Business-Catalogs (1878–1958), Cambridge Historical Commission. The recipient of this brochure was the Thomasville Chair Company, in North Carolina. It expressed interest in a number of items, prompting the following response from Kaplan, indicating a quick turnover of inventory: “Replying to your letter of the 19th inst. The glass of the #91 Beverly Cabinet, #1897 and #197A Secretaries are millioned. The slides that support the writing bed of our desks is approximately 4" wide. We are in a position to make immediate shipment of the #171/2 Bookcase. We trust that you have found these pieces of sufficient interest to warrant your placing an order with us for them.” A catalogue was meant to accompany this price guide, which might explain discrepancies in price between a $175 highboy and a $220 highboy. The whereabouts of this catalogue is currently unknown. The only distinct entry in this price list is a dining table in the “Duncan Phyfe” style, costing $35 more than a table with the exact same dimensions, sans title. Kaplan Furniture Company to Thomasville Chair Company, 1926, Kaplan Furniture Company Archive, Col. 805, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum & Library. Kaplan Furniture Company, Price Guide to the K-C Line of Colonial Furniture (1926).

Rossiter, “Magic Rise of Kaplan,” pp. 60-61.

David Kaplan, e-mail interview by the author, April 2016.

Kaplan Furniture Company, The Beacon Hill Collection as Interpreted by B. Altman & Company (Cambridge, Mass.: University Press, 1940). Probably as many as 40 percent of Kaplan’s workforce had worked the cabinetmaking trades before they migrated, bringing with them an established skill set, which could immediately be put to work in the New World. Smith, “Greeners and Sweaters,” p. 106. Gale, “Leaders in the Industry,” p. 1. Frederick R. Love, “Period Style Furniture for High School Work,” Industrial Arts Magazine 7, no. 4 (April 1918): 135. Andrew Roswell, “Trade School Cabinetmaking,” Furniture Manufacturer and Artisan (September 1920): 142; Frederick J. Bryant, “Furniture Fashions of Long Ago,” Manual Training Magazine (October 1919): 46–53.

George S. Schuyler, “Craftsman in the Blue Grass,” The Crisis (May 1940): 143. Other black vocational schools emphasized colonial designs as inherently honest and moral, with regards to materials, as detailed in Ellen Weiss, Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee: An African American Architect Designs for Booker T. Washington (Montgomery, Ala.: New South Books, 2011), p. 128.

Greenfield, Out of the Attic, p. 86; Phillips, “Almost History,” p. 50.

Early scholars on the subject of antiques emphasized a mixture of reverence toward authenticity and a taxonomic appreciation of design styles. An important early example was the quarterly bulletin distributed by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England), established in 1910. Working out of Boston, founder William Sumner Appleton (1874–1947) and his society raised standards in early American homes and furniture. Contemporaneous with these types of organizations were publications aimed at collectors of historic objects with hints about how to identify authentic antiques. Walter Dyer, The Lure of the Antique (New York: Century, 1910); Alice Van Leer Carrick, Collector’s Luck (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1919); Alice Van Leer Carrick, The Next-to-Nothing House (Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922). Wallace Nutting established Wallace Nutting Incorporated in 1917, and the company lasted until 1945. Thomas Denenberg, Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003), p. 165-167.

Frances Gruber Safford, American Furniture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Volume 1 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007), p. 6. Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury (New York: Old America Company, 1928), 2: no. 3136.

Denenberg, Wallace Nutting, p. 91. Kaplan Furniture Company advertisement, Koppers Magazine.

Kaplan Furniture Company, Beacon Hill Collection.

As evidence of his assimilation, Kaplan was a trustee of the Boston Psychopathic Hospital, Associated Jewish Philanthropies, Cambridgeport Savings Bank, and an active Mason and Rotarian. Gale, “Leaders in the Industry,” p. 1.

Stone, History of Massachusetts Industries, 4: 20.

One advertisement broke down this process: “For $1368, which includes the cost of fabric for the upholstered pieces, you can feature fourteen pieces of related home furnishings in an appropriate 16 foot square setting. This unit is planned and designed by the makers of the famous Beacon Hill Collection to attract and sell to customers of moderate means who desire home furnishings of fine quality and design. Your maintenance man can erect the attractive setting easily with working plans which we provide.” Kaplan Furniture Company Archive, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum. Clifford Clark Jr. drew an analogy between department stores and museum spaces, as stores placed “a status hierarchy of objects [with] works of art at the top and encouraged the consumers continuously to try and raise their standards.” Clark Jr., The American Family Home, 1800-1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p.127.

Harold Margolis, interview by Don Fennimore, October 13, 1976. Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum & Library.

Kaplan Furniture Company, Beacon Hill Collection, p. 5. Although available archival information provides few details on the particulars of Kaplan’s business partnerships, a lawsuit in the 1960s between the Kaplan Furniture Company and W&J Sloane sheds light on how the marketing and branding of the Beacon Hill Collection operated. W. & J. SLOANE, INC. v. KAPLAN FURNITURE COMPANY and Knapp & Tubbs, Inc., 232 F. Supp. 791, United States District Court S. D. New York, 1964.

“Remarkable Collections of Miniature Furniture at Paine’s,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 28, 1938. Three rooms of antique-model furniture, scaled down to miniature size, were shown at the World’s Fair; their value was said to be $20,000. The designer was Dexter Spaulding. Gale, “Leaders in the Industry” p. 1.

Advertisement for Kaplan Furniture Company, box 70, col. 805, Kaplan Furniture Company Archive, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum & Library. See notes 11 and 24.