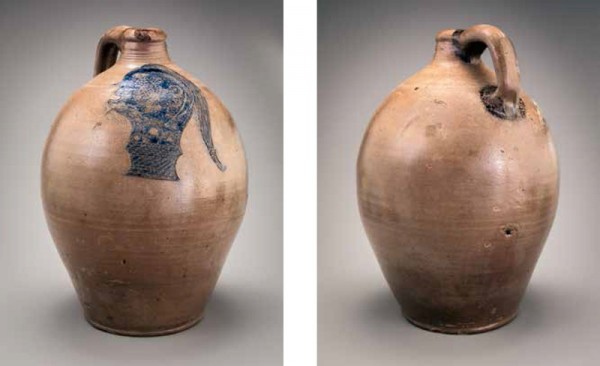

Jug, attributed to the Crolius family, probably John Crolius or John Crolius Jr., New York, New York, ca. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the handle from the jug illustrated in fig. 1. Note the use of manganese to highlight the handle terminals, and the distinctive thumb dimple used for the lower one.

Detail of the bottom of the jug illustrated in fig. 1. The small square patch reads “25”; the larger label reads “South Amboy Remmey / (Indian Head).” Note the distinctive circular marks created when a wire was used to cut the wet jug from the potter’s wheel head.

Illustration from W. Oakley Raymond’s article in The Antiquarian 9, no. 6 (January 1928): 41. The red arrow points to the jug, in the front row of the display.

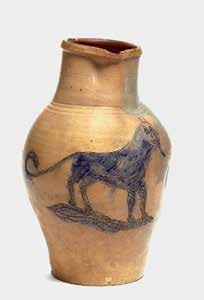

Jug, attributed to John Crolius or John Crolius Jr., New York, New York, ca. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm.) The jug is now part of the Adam Weitsman stoneware collection at the New York State Museum.

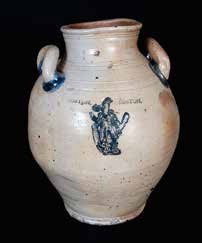

Jug, Clarkson Crolius or John Crolius, New York, New York, 1800–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Museum of the City of New York.) The incised scene on the jug commemorates November 25, 1783, when the British forces that had occupied New York City left for good, subsequently, celebrated as Evacuation Day by generations of New York residents.

Pitcher, attributed to John Crolius or John Crolius Jr., New York, New York, 1796. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Courtesy, The New York State Museum.)

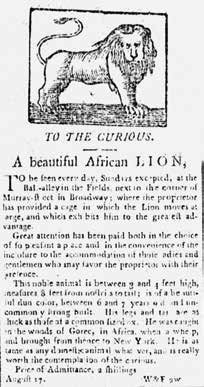

Advertisement, The Minerva & Mercantile Evening Advertiser, August 17, 1796. (Courtesy, New York State Library.) The ad announces the exhibit of an African lion in Manhattan.

Presentation basin, southeastern Pennsylvania (likely Philadelphia), ca. 1730–1760. Trailed slipware. D. 14". (Courtesy, The National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania at Stenton; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

John Simon (after Jan Verelest), Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maquas [Mohawks], ca. 1710. Mezzotint on laid paper. 13 1/2 x 10 1/16". (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.)

Jar, Jonathan Fenton (1766–1848), Boston, Massachusetts, late eighteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 3/4". Marks: stamped twice, “BOSTON.” (Courtesy, Crocker Farm.)

Detail of the Native American figure on the jar illustrated in fig. 11.

Tavern sign, Rehoboth, Massachusetts, ca. 1810. Wood and iron. (Collection of Leslie and Peter Warwick; photo by Williamstown Art Conservation Center.) This image of a Native American is similar to one on the Massachusetts

state seal.

Detail of the Native American profile incised on the jug illustrated in fig. 1.

Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), after John White (fi. 1585–93), An Ageed Manne in His Winter Garment, Frankfurt, Germany, 1590. Hand-colored engraving on laid paper. 6 1/8 x 8 11/16". (Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)

Detail of the “Ageed Manne” illustrated in fig. 15 showing the facial hair on the chin and upper lip.

Badge or pendant, Jamestown, Virginia, ca. 1607–1617. Copper alloy. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation [Preservation Virginia]; photo, Michael Lavin/Jamie May.) Discovered in a ca. 1607–1617 cellar in James Fort, this object appears to represent Chief Powhatan (Wahunsonacock).

Gustavus Hesselius (1682–1755), Tishcohan, ca. 1735. Oil on canvas. 33 x 25". (Philadelphia History Museum, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, Gift of Granville Penn.)

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Joseph Brant/Thayendanegea (1742–1807), ca. 1797. Oil on canvas. 25 1/2 x 21 3/8". (Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.) This portrait was made by Peale during a diplomatic visit to Philadelphia by Brant and other Native leaders. The floral headdress and absence of weapons indicates a mission of peace.

William Berczy (1744–1813), Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant), ca. 1807. Oil on canvas. 24 5/16 x 18 1/8". (National Gallery of Canada.) This imagined portrait set in a bucolic landscape was inspired by Brant’s death in 1807.

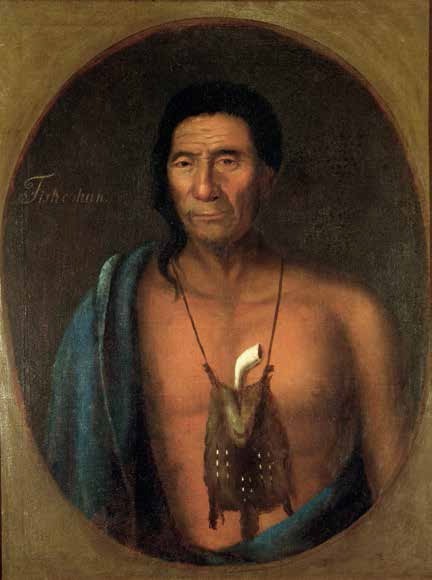

Powder horn that belonged to Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), ca. 1790. Cow horn, wood, and iron. L. 8". (Courtesy, Joseph Brant Museum, 2003.13.1.) Brant is thought to have used this powder horn during the latter part of the 1700s. The horn is engraved with decoration of various wildlife including birds, fish, a deer, a turtle, beaver, porcupine, and two indigenous heads.

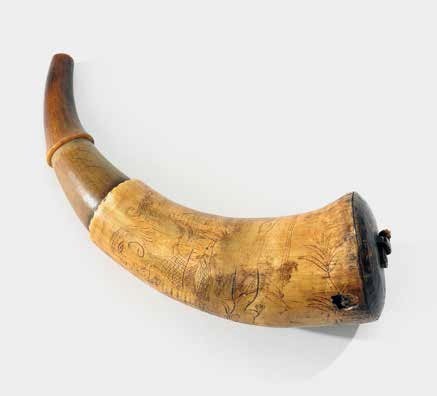

Detail of one of the Native American profiles on the powder horn illustrated in fig. 21.

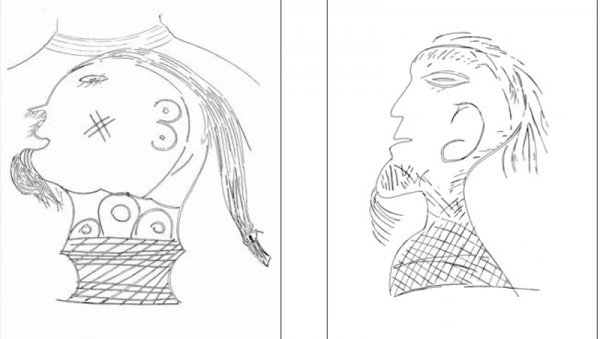

Artist drawings comparing the incised lines on portraits on

the Manhattan stoneware jug on the left and the Joseph Brant powder horn on the right. (Drawings, Oliver Mueller-Heubach.) The stylized effect of the incising technique is evident on the outcome of both portraits. The facial hair on both men is clearly and carefully delineated with in the incising. It is interesting that the technique of cross-hatching is used on the lower neck and chest area. The constriction on the lower neck of the stoneware portrait, however, might correspond to a neck cloth or stock as seen in the portrait illustrated in fig. 24.

Frederick Bartoli, Ki On Twog Ky (also known as Cornplanter), 1732/40–1836, 1796. Oil on canvas. 30 x 25". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society, Gift of Thomas Jefferson Bryan.) This bust-length portrait shows Cornplanter’s cut earlobes and the accoutrements of the ranking chief of the Seneca tribe. Note the neckcloth, or stock, a fashionable device among American and European gentlemen that was also restrictive and uncomfortable.

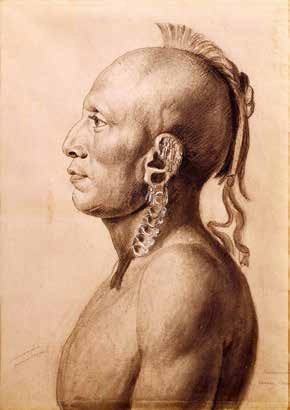

Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin (1770–1852), Unidentified Osage (Chief of the Little Osage), 1804. Charcoal with stumping, black pastel, black and white chalk, Conté crayon over graphite on pink prepared paper, nailed over canvas to a wooden strainer. 22 3/4 x 16 3/4". (The New-York Historical Society, 1860.93.) The subject of this portrait was one of five Osage chiefs invited by President Jefferson to Washington in 1806.

John Vanderlyn (1775–1852), The Murder of Jane McCrea, 1804. Oil on canvas. 32 1/2 x 26 1/2". (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 1855.4.)

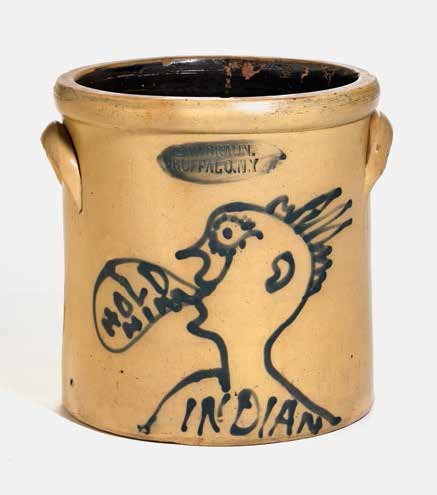

Storage jar, Charles W. Braun, Buffalo, New York, ca. 1890. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, The New York State Museum.) Depicted in brushed cobalt, this Native American figure was inspired by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Taken from one of the scenes of Indian raids that were part of the show, the “Indian” is shouting “Hold him.”

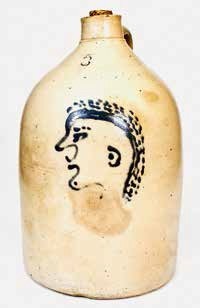

Jug, attributed to New York State, ca. 1875. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. not given. (Courtesy, Crocker Farm.)

Trench-art artillery shell, American, ca. 1917–1919. Carved brass. H. 13 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Inscribed “28th / SQUADRON.” The 28th Aero Squadron was an Air Service unit of the United States Army that fought on the Western Front during World War I. A Native American warrior was used as their insignia, and is still in use today by the 28th Bomb Squadron of the United States Air Force.

Detail of the carved artillery shell illustrated in fig. 29.

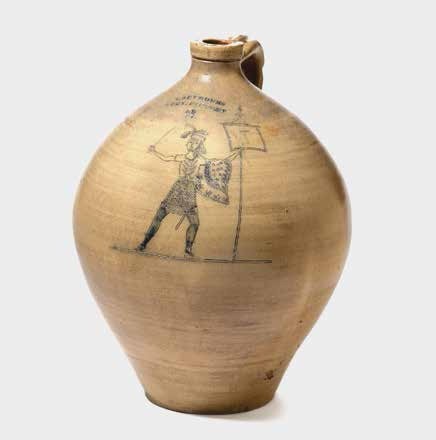

Jug, Israel Seymour (1784–1852), Troy, New York, ca. 1815. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14". (Courtesy, The New York State Museum.) The elaborately incised figure represents the Seneca chief and prophet Handsome Lake.

Detail of the incised figure on the jug illustrated in fig. 31.

Introduction: The stoneware jug appeared in a late-night Facebook feed, as I scrolled through the offerings of various antique dealers posting their “booth shots” from a prominent New England antique show (fig. 1). Social media platforms have transformed the antique business into a twenty-four-hour slideshow with access to items for sale throughout the world. Collectors and dealers have to be vigilant to be first to catch the latest posting in this highly competitive virtual market.

In this instance, I was immediately drawn to the ovoid shape of the jug among its straight-sided and highly embellished companions sporting cobalt peafowl, horses, and lions. The graceful form told me I was looking at a very early nineteenth-century vessel, probably of New York City origin, the period of American stoneware that interests me most. The jug was decorated with an incised composition, highlighted in cobalt, that I first thought was an elaborate basket of flowers, a common motif used by early decorators.

In the instant message sent by the dealers, well-known purveyors of good American stoneware, came exhaustive pictures of the jug.[1] To my amazement and great delight, what I thought was a floral bouquet turned out to be a highly detailed, nuanced profile portrait of a Native American male. My mind immediately went into overdrive trying to recall other early examples of Natives depicted on early American pottery, but I could recall nothing this early or detailed.

I made arrangements to purchase the piece, and once it arrived and was unpacked, the detective work began. The incised profile is remarkable, and the jug, which is well thrown and sturdy, bears the undeniable earmarks of Manhattan-style stoneware. The numeral 3 is used in the composition to represent the ear of the Native as well as to indicate the gallon size of the jug. The distinctive use of both cobalt slip for the decoration and a manganese slip to highlight the handle terminals is a characteristic feature found on late-eighteenth-century Manhattan stoneware (fig. 2).

Collection History and Attribution

No collection history came with the jug, but I later discovered that it had been sold in 2002 at a Skinner’s Auction in Boston.[2] The catalog entry stated that the jug had once been in the collection of famed early-American-ceramics historian W. Oakley Raymond. On the bottom of the jug, pasted over the wire marks where it had been cut from the wheel, are two linen labels with handwritten notations (fig. 3). The first label is a small square patch that reads “25,” which suggests that Raymond had a substantial collection underway. The other label, presumably applied by the early collector, bears the much more informative “South Amboy Remmey / (Indian Head)” and indicates his thoughts as to origin of the piece and his belief that the profile was intended to represent a Native American.

Raymond had pictured this jug in the January 1928 issue as part of an article titled “Colonial and Early American Earthenware.”[3] The jug is seen in a large group shot, but the distinctive incised decoration is barely discernible in the photograph (fig. 4). The accompanying text does not even mention the image of the Native American but goes on to say “[s]imilar crocks are sometimes incised ‘Made by J. Letts, Liberty, for Ev.’ ” Oakley further cites Edwin Atlee Barber regarding the attribution: “Following the closing of the New York Factory run by three generations of John Remmeys, about 1820 (ten years after Richard C. Remmey went to Philadelphia), Joseph Henry Remmey, a great grandson of John Remmey, the founder, moved to So. Amboy, N. J., with some of the machinery of the old factory and established a pottery there.”

The attribution to Joseph Remmey in South Amboy is at odds with current scholarship, however. The eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century stoneware industry in Manhattan was dominated by the Remmey and Crolius families, who are considered to be the most significant stoneware potters in early Colonial America. The history of those potting dynasties have been well discussed, and their products have been collected vigorously by museums and collectors for more than a century.[4] In spite of the vast scholarship related to these wares, making definitive attributions of unmarked wares continues to be difficult in the absence of documentary evidence or archaeological parallels. This is compounded by the fact that the Crolius and Remmey potters often intermarried, shared the same kilns and materials, and exchanged workers within the confined space of lower Manhattan.

Current efforts to identify specific makers and decorators rely almost exclusively on the encyclopedic documentation of stoneware that comes through the auction house Crocker Farm. Owned by the Zipp family, its current database contains dozens of examples of early-nineteenth-century New York stoneware. Many can be firmly attributed to the Crolius, Remmey, or Commereau manufactories, others can be only generally assigned to the Manhattan area.

One particular three- or four-gallon jug in the Zipp database is nearly identical to the Native American portrait jug in size, shape, and finish (fig. 5). It has a large, incised fish filled in with cobalt. The fish faces to the left as does the Native American, ostensibly further evidence that both portraits were by the same decorator.[5] Like the Native American profile, the incising on the fish is very deliberate, without hesitancy or noticeable errors, indicating that the decorator was skilled and practiced. The Zipps suggest the attribution of Crolius family as their best guess. The jug was acquired for the Adam Weitsman collection of American stoneware at the New York State Museum; the museum suggests that the jug is the product of either John Crolius, working circa 1775–1800, or John Crolius Jr., who worked from 1779 to 1812.[6]

Stoneware was first and foremost a utilitarian product that served the needs of American households in the storage of foods, oils, paints, and other caustic liquids. Its presence was universal in American homes and businesses through the end of the nineteenth century. Much of the American industry was spawned from Germanic immigrant potters who were trained in the Westerwald style of stoneware. Westerwald potters were known for their precise incised designs and the durable, high-gloss, salt-glazed finish. American stoneware potters also used the walls of their jars and jugs as blank canvases, perfect for aesthetic expressions.

While most American stoneware was undecorated except for a simple flourish of blue cobalt slip, a few examples rise to the level of fine art, with intricate images of flowers, birds, fish, and other animals. Sometimes decoration was of a more personal nature, reflecting perhaps the whimsy of the decorator.

The most elaborate decoration is often found on objects that commemorate specific historical events, from important battles to presidential campaigns. The commemorative jug illustrated in figure 6 is a good example, although the event is probably not well remembered by most students of American history—November 25, 1783, the date when the British forces that had occupied the city during the Revolutionary War years finally departed for good. Known as Evacuation Day, this date became a local holiday and subsequently was celebrated by generations of New Yorkers. The jug now resides in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York, where it is cataloged as the work of Clarkson Crolius or possibly John Crolius, and made between 1800 and 1805.

Somewhat surprising, the jug was made perhaps twenty years after the event it commemorates, so fictional bits of folk lore undoubtedly had crept into the collective memory of New York’s citizenry. The incised scene records the greasing of the flagpole atop of New York’s Fort George by fleeing British troops to impede the Americans from pulling the British flag down. The potter added cartoon balloons for the figures of two British soldiers with the captions “Damn the rebels, I will give them some trouble,” and “Slush [grease] it well, Johnny.”

While the Evacuation Day jug is a reminder not to assume that a historical event recorded on stoneware is contemporary with the manufacture of the object, contemporary events do inform the decoration of many stoneware compositions. In fact, engravings and newspaper illustrations often serve as direct inspiration for ceramic (stoneware or otherwise) decorators.

The early New York pitcher illustrated in figure 7 is another example from the Weitsman Collection that provides insight into how a newspaper illustration might have inspired a stoneware decoration. The pitcher, which is attributed to either John Crolius or John Crolius Jr., is thought to date to 1796, the year in which an advertisement announced a traveling menagerie that was visiting New York City (fig. 8).

Depictions of Native Americans on Early Ceramics

Since the discovery by Europeans of the American continents, representations of the aboriginal inhabitants have taken many forms, appearing in early cartographic and ethnographic drawings and engravings. The character of the Native American image varied considerably, from accurate renderings to stylized, derogatory caricatures that still persist.[7] Beginning in the eighteenth century, Native Americans became the subject of fine portraiture by leading artists in Britain and America. By the turn of the nineteenth century, such images were being used on tavern signs, as tobacconist figures and weather vanes, and engraved into powder horns, medals, and other brass and silver accoutrements.

Only two other known American-made ceramics objects depict or reference Native Americans earlier than the ca. 1800–1810 portrait jug shown in figure 1. The first example is a slip-decorated earthenware bowl or basin found by archaeologist Barbara Liggett in 1982 on the site of Stenton, the home of James Logan, an American statesman and William Penn’s secretary, in North Philadelphia (fig. 9).

The bowl was discussed in the 2008 Ceramics in America and readers are referred there for further detail, but for this discussion it is essential to note that the slip-decorated Native American figure was inspired by a print image of the Mohawk chief Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow (fig. 10).[8] The engraving was taken from a painting by Dutch artist Jan Verelst (1648–1734) of the four Iroquois delegates who visited London, and the court of Queen Anne, in 1710.[9]

In the translation from an engraved print to a painted ceramic surface, the limitations of the slip-decorating technique renders the image on the bowl as a cartoon-like figure. Typically, this incongruity is carried over to images on both incised and slip-decorated stoneware so that, despite the skill and dexterity of the decorator, the results are often very stylized, cartoonish line drawings.

The jar illustrated in figure 11 was made by Jonathan Fenton of Boston about 1790. It is the earliest recorded stoneware object to include an image of a Native American. Rather than a specific individual, the figure on the jar is generalized, impressed or stamped into the clay body and subsequently highlighted with cobalt slip (fig. 12). No facial features are apparent but the accoutrements of the costume, among them bow and arrows, are clear. Research by Crocker Farm, who recently sold the jar, suggests that the figure was copied from the State Seal of Massachusetts, designed in 1780 by a man named Nathan Cushing and subsequently engraved by Paul Revere.[10] The original engraving by Revere has not survived, but the image was also the source for inspiration for other mediums, possibly including the ca. 1810 tavern sign illustrated in figure 13.[11]

Deciphering the Manhattan Native American Portrait Jug

To find a stoneware depiction of a Native American of the quality as seen on the portrait jug is extraordinarily rare (fig. 14). Both the Stenton bowl (see fig. 9) and Boston jar (see fig. 11) have very elementary representations of Native Americans, despite the intent and best efforts of their decorators. The more defined rendering of the image on the Manhattan jug permits analysis of the much deeper historical and symbolic information contained within the portrait. One immediate question is whether it represents a specific individual or a generalized Native American male.

The incised image is a relatively large composition measuring over six and half inches in height and is carefully drawn with a sharp stylus dragged through wet clay. Incised decoration is unforgiving: once a line is cut into the wet clay body, it is difficult to erase or correct an error. Discrete elements on the portrait include the long braid from the top of the scalp, called a scalp lock. A tattoo or scarification on the cheek is represented by a hash mark. The use of the numeral 3 suggests a split earlobe, a common trait among earring wearers, but also results in a clever visual pun denoting the gallonage of the jug. The lower neck is ornamented with three circular devices that probably represent the trade silver gorgets worn by Native warriors.

The most exceptional aspect of the profile is the carefully drawn and delineated beard flowing from the chin and the additional facial hair on the individual’s upper lip. The presence of this thin but obvious beard growth was confusing to several collectors and scholars that I consulted. Many commented that Native Americans do not grow facial hair, or pluck it to keep a bare face. This opened an avenue of research that I never thought an American ceramic object would lead me to—the record of Native American facial hair in art.

The topic of Native American physiognomy and facial hair in fact has a long history.[12] Early chroniclers of America are the first source of discussion on male facial hair within Native American populations. In 1585 the Englishman John White, governor of the ill-fated colony of Roanoke in what is now North Carolina’s Outer Banks, made watercolor sketches of the native Algonquians of the Carolinas and Virginia. In 1590 Theodor de Bry engraved versions of White’s paintings to illustrate scientist and ethnographer Thomas Hariot’s The Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. Describing the image of the “ageed manne” shown in figures 15 and 16, Hariot comments: “The yonnge men suffer noe hairr at all to growe vppon their faces but assoone as they growe they put them away, but when thy are come to yeeres they suffer them to growe although to say truthe they come opp verye thinne.”[13]

Other early Virginia colonists made note of facial hair among the Native populations. Explorer George Percy, one of the first colonists to settle at Jamestown, observed an aged Native American in one of the Pamunkey Inidian villages: “. . . wee saw a Savage by their report was above eight score yeeres of age. His eyes were sunke into his head, having never a tooth in his mouth, his haire all gray with a reasonable bigge beard, which was as white as any snow. It is a Miracle to see a Savage have any haire on their faces. I never saw, read, nor heard any have the like before.”[14]

Powhatan (Wahunsonacock) was a powerful chief who ruled over the majority of the indigenous tribes in the Chesapeake Bay region. Captain John Smith, who helped established and govern the Jamestown colony, described meeting the great chief in December 1607: “He is of personage a tall well proportioned man, with a sower [sour] looke, his head somwhat gray, his beard so thinne that it seemeth none at al, his age neare 60; of a very able and hardy body to endure any labour.”[15]

Another early English reporter of Virginia history, William Strachey, observed Powhatan’s features in 1610–11 and noted “some few haires upon his Chynne, and so on his upper lippe.”[16] A fascinating artifact found in a circa 1607–1617 context at Jamestown—a small copper pendant or badge thought to be a profile portrait of Powhatan—may provide visual confirmation of the great chief’s facial hair (fig. 17). Striations incised along the jaw seem to correlate with the accounts of Powhatan’s wispy beard.[17]

Julianne Jennings, a Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) who co-authored A Cultural History of the Native People of Southern New England, has written about Native American facial hair, describing it as a conscious choice, depending on the tribe.[18] She cites Englishman William Wood’s observations of the Aberginians tribe made during his time in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1629 to 1633: “you cannot wooe them to weare it on their chinnes, where it no sooner growes, but it is stubbed up by the rootes, for they count it as an unuseful, cumbersome, and opprobrious excrement, insomuch as they call him an English mans bastard that hath but the appearance of a beard, which some have growing in a staring fashion, like the beard of a cat, which makes them the more out of love with them, choosing rather to have no beards than such as should make them ridiculous.”[19] In the culture of these Natives, the appearance of a beard was not just undesirable, but considered shameful, even disgraceful.

Throughout the seventeenth century, Native American facial hair continued to a be subject for commentary by English travel writers. Recent writing by Eleanor Rycroft on the sociopolitical meanings embodied by Native American facial hair show it to be a complex topic linked to discussions of colonialism, civility, and virility.[20] The English chroniclers overtly suggested that the Native American males were less masculine than their full-bearded English counterparts, one of many ways of rationalizing the subjugation of the Native populations.

More formal portraiture of Native Americans took place beginning in the eighteenth century. Among the earliest examples are the painted portraits of the so-called Four Indian Kings—three of whom were Mohawk chiefs and one a Mahican chief of the Algonquian-speaking peoples—by Dutch painter John Verelest, who recorded their visit to London and the court of Queen Anne in the spring of 1710. Those full-length portraits were much celebrated at the time, and numerous engraved copies were produced for many years to come.[21] As mentioned, the engraved version of the painting of Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow was to serve as the source image for the Stenton slipware decorated basin discussed above (see figs. 9, 10).

The next significant portraiture occurred in America in 1735, when Swedish artist Gustavus Hesselius (1682–1755) made portraits of two Lenape chiefs, Lappawinsoe and Tishcohan, of the Delaware tribe (fig. 18). The chiefs had sold land to John and Thomas Penn, sons of William Penn, in a transaction called the Walking Purchase Treaty of 1735/1737. The exact circumstances of the commission of the portraits is unknown, but it is plainly tied to the signing of the treaty. Of special note, Tishcohan is shown with “bunch of hair growing from under his lip and chin.”[22]

Richard H. Saunders and Ellen G. Miles commented on the Tishcohan portrait: “Hesselius portrayed Tishcohan with an objectivity that distinguishes this painting from many of the portraits painted in the 1730s in the American colonies, in which artists sought to portray their sitters according to current European standards of beauty, grace and elegance.”[23] The inclusion of Tishcohan’s scraggily chin whiskers undoubtedly went a long way in forming the authors’ assessment of Hesselius’s “objectivity.”[24]

The most famous and recognizable Native American of the later eighteenth century was Chief Joseph Brant (1743–1807), whose Mohawk name was Thayendanegea. Educated in English under the tutelage of Sir William Johnson, the powerful British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Brant rose to prominence through his alliance with the British during the Revolutionary War and subsequently through his diplomatic abilities to win back the favor of most Americans. He was at home among the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga, and Tuscarora nations, the six tribes that formed the Iroquois Confederacy, as well as negotiating with various American, British, and Canadian officials.

Brant’s life has been recounted in numerous biographies and articles, and his exploits during his military raids against the American forces were chronicled in contemporary newspapers and broadsides.[25] After the war he remained highly visible in the press, as he made trips to London, meeting with King George III, and to the American capital, Philadelphia. During those trips he sat for the most notable artists of the time (fig. 19), earning the reputation as “The Most Painted Indian” in America.[26] Gloria Lesser has analyzed thirty-nine Brant portraits, including original paintings by Ezra Ames and also George Romney, Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale, and William Berczy.[27] Those portraits, along with innumerable copies and derivatives, reflect the importance of Brant as seen through the eyes of British and American white culture. Brant himself made sure to dress in Mohawk costume for the sittings. In every single portrait, he is shown without a hint of facial hair. Ironically, it is through Brant’s own writings we gain the most insights into the question of Native American beards.

Brant was extremely literate and an astute ethnographic recorder and commentator on Native American facial hair, as seen in his response to a query in 1783:

The men of the Six Nations have all beards by nature; as have likewise all other Indian nations of North America, which I have seen. Some Indians allow a part of the beard upon the chin and upper lip to grow [emphasis added] and a few of the Mohawks shave with razors, in the same manner as Europeans; but the generality pluck out the hairs of the beard by the roots, as soon as they begin to appear; and as they continue this practice all their lives, they appear to have no beard, or, at most, only a few straggling hairs, which they have neglected to pluck out. I am, however, of opinion, that if the Indians were to shave, they would never have beards altogether so thick as the Europeans; and there are some to be met with who have actually very little beard.[28]

Also connected to Brant is the most significant visual evidence of Native facial hair relating to the incised image on the stoneware jug. An engraved powder horn that was owned and used by Brant in the 1790s resides in the collection of the Joseph Brant Museum in Burlington, Ontario.[29] Built in 1937 as a replica of Brant’s house, the museum is undergoing significant expansion to house and interpret his personal effects, and the powder horn came to the collection through a descendant of an adopted daughter of Joseph Brant. A powder horn of this type is shown in William Berczy’s circa 1807 full-length portrait of Brant (fig. 20).

The powder horn is made of cow horn, and is engraved with birds, fish, a deer, a turtle, beaver, and a porcupine (fig. 21). In addition, and most significant, are two Native American profile busts of males. Both figures are depicted with distinctive but wispy beards on their chins. Figure 22 illustrates a detail of one of the figures. A side-by-side comparison of the incised decoration on both the stoneware jug and the Brant powder horn is shown in figure 23.

It is not known whether Brant himself is responsible for the engraving on the powder horn or whether the work was done by another, presumably Native American artist. The immediate point of interest for illustrating the powder horn is the pictorial corroboration of his observation that “some Indians allow a part of the beard upon the chin and upper lip to grow.”

The question of whether the two individuals illustrated on the horn were men known to Brant or were just generic representations is difficult to answer. We do know that many of Brant’s contemporaries included the best-known members of the Iroquois Confederacy.[30]

One of these was the Seneca chief Cornplanter (1732/40–1836)—or Kaiiontwa’kon (“By What One Plants”) in the Seneca language—whose formal portrait was made in 1796 (fig. 24). The painting gives us a sense of the full regalia worn by an Iroquoian chief.[31] Cornplanter, who also served as a war chief with the British during the American Revolution, made trips after the war to Philadelphia and New York in diplomatic missions to strengthen relationships between the Iroquoian Confederacy and the Americans. His portrait is of interest as it shows his cut earlobes and silver gorget. Of particular significance is his cloth neck wrap, which has been identified as a stock, a fashionable but restrictive neck band or scarf worn by American and European gentlemen which typically is wrapped around the neck and knotted or buckled in front.[32] It’s possible that the stoneware portrait displays a stock as indicated by the curved and cross-hatch constricted element on the lower part of neck. Although Cornplanter was a well-known name in the early nineteenth century, there is no indication he wore facial hair.

Another of Brant’s contemporaries, the Seneca chief Little Beard (Si-gwa-ah-doh-gwih, meaning “Spearing Hanging Down”) is perhaps of the greatest relevance to the possible identification of Manhattan jug portrait. Little Beard participated in the American Revolutionary War on the side of Great Britain and fought alongside Brant. Little Beard attained a notorious reputation for his exploits during the war, although he was described “as amiable and he made friends with the white settlers after the war.”[33] Living in what is now Leicester in Livingston County, New York, like Brant he ultimately made peace with the Americans. He died following what was termed a drunken brawl at a Leicester tavern on or around June 1, 1806. No contemporary announcement of his death has yet to be found in period newspaper searches, but historical accounts continued to repeat the story of his death well into the twentieth century.

Several sources noted that Beard’s death coincided with the Great Eclipse of 1806, which occurred on the evening of July 16.[34] The story of the solar event of 1806 was widely reported in American and European newspapers and the event was recounted many years afterward.[35] From the biographical tale of Mary Jemison, a white woman who had been adopted as a Seneca in 1755, comes the anecdote that the Natives who lived in the adjoining towns near the Genesee River attributed the eclipse to Little Beard’s death and some unresolved grievance. To appease the spirit of the chief, the Natives shot arrows and bullets into the sky until “the old fellow left his seat, and the obscurity was entirely removed, to the great joy of the ingenious and fortunate Indians.”[36]

From his English name alone, one might presume that Little Beard is the best candidate for the individual portrayed on the stoneware jug. Unfortunately, of all the well-known Iroquoians of the late eighteenth century, Little Beard is the only one for which period illustrations have not been found. Physical descriptions generally conclude that “he was a favorable specimen of the Indian chieftain, rather below the medium size, yet straight and firm.”[37] No mention of his facial hair has been located, however, to support the supposition that he truly wore a beard as suggested by his name.

Joseph Brant passed away in 1807 at his home in Burlington, Ontario. His death was noted in the contemporary press.[38] Despite his fame, all pictorial evidence suggests that Brant deliberately went without facial hair, although the engraved images on his powder horn suggest some of his compatriots wore beards.

The first decade of the nineteenth century was a period of high visibility for Native American portraiture in the New York City area. At the request of President Thomas Jefferson, Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin (1770–1852), a French artist working the United States, produced eight portraits of members of Native American delegations visiting Washington, D.C., between 1804 and 1807.[39] He worked using a device called a physiognotrace, an instrument that traced the physical features of his subjects and consequently permitted remarkable accuracy. Figure 25 illustrates a portrait of an Osage warrior with a shaved head and split earlobe that in profile is very similar to what is seen on the stoneware jug. This Native is shown wearing European-style clothing, including the neck cloth or stock, previously identified as an element of the stoneware portrait’s composition. Saint-Mémin may have sold prints of these works in his New York City shop until he returned to France in 1814.[40] None of the surviving Saint-Mémin portraits or prints shows Natives with facial hair, however.

Another well-publicized Native-themed painting found its way to New York City in 1805. The melodramatic portrayal of The Murder of Jane McCrea by American artist John Vanderlyn (1775–1852) (fig. 26) was accepted to the Paris Salon of 1804 and became the first American work to be exhibited there.[41] The controversial death of Jane McCrea purportedly at the hands of Wyandot scouts for the British Army during the American Revolution fueled American anti-Native propaganda and became the subject of exaggerated images and rallying songs and poems.[42] Although the accounts of the brutality surrounding her death were probably greatly overblown, the Vanderlyn painting became emblematic of the tragic event; in 1805 it returned to New York for public viewing and hung in the Academy of Fine Arts until 1842. It is suggestive, course, but the powerful image and the effect it had on the public, may have been a source of inspiration for the Manhattan stoneware decorator.

Further Thoughts

In the course of my research on this topic, I solicited a variety of opinions about what the image on the stoneware jug represented; a number did not agree with mine.[43] The dissenting opinions ranged from a severed trophy head mounted on a plinth to the possibility that it was not a Native American at all but rather an African American. I still believe strongly that it is a portrait of a Native American, and that its rendering was based on a historical precedent.

While extremely rare, Native Americans have been the subject for other American stoneware objects, although those generally were produced much later in the nineteenth century. For example, the stoneware jar in figure 27, which was made and decorated in Buffalo, New York, around 1890, was inspired by a scene from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.[44] This example includes the word “Indian” in the sketch-like man’s profile, firmly identifying the decorators’ intent, which otherwise might have been a subject of debate. Another stoneware jug from about 1875 has a cobalt-decorated Indian head with Mohawk-style hair (fig. 28).[45] Unlike the previous Buffalo Bill example, this “portrait” takes the form of a disembodied head.

The disembodied-head aspect led to a deeper, more sinister journey into what appears to be a long-held and purposeful stereotyping of Native American images.[46] Critical writers have cited numerous examples, from coins to the helmets of the NFL football team Washington Redskins that picture Native heads, particularly chiefs or warriors in this fashion.[47] Figure 29 illustrates a World War I trench-art brass artillery casing with the insignia of the 28th Aero Squadron, a version of which is still used by the 28th Bomb Squadron of the United States Air Force. For better or worse, the Native American profile (fig. 30) is remarkably similar to the jug with protruding chin, open mouth, and the tattoo or scarification on the cheek signified by an “X.”

The motives of the decorator of the portrait jug and the identification of the Native American individual may never be known in the absence of a corroborating pictorial or documentary source. The image might be merely a whim or artistic impulse of the decorator, but the level of detail in the composition suggests an intention to record a specific individual, associated with a specific historical event or to mark an occasion, such as death. The attention paid to discrete elements—such as the tattoo or scarification, the scalp lock, the trade silver disks or gorgets, even the fashionable stock—suggests that the decorator was making an honest attempt at portraiture rather than caricature. The cartoonishness of the image can be attributed to either the naïveté of the artist or the difficulty inscribing wet clay, or both. The human figures and animals shown on the Brant powder horn help confirm the limitations of the incising technique for true renderings.

For most of this discussion, members of the Iroquois Confederacy have been identified as possible subjects for the portrait on the Manhattan stoneware jug. Another stoneware jug in the Weitsman Collection at the New York State Museum provides precedence that Iroquoian figures were indeed subjects of interest for utilitarian stoneware potters (fig. 31).[48] A two-gallon jug made by Israel Seymour of Troy, New York, commemorates the death of the Seneca chief Handsome Lake (ca. 1734–1815).

Handsome Lake was a contemporary of Joseph Brant and Little Beard, and a half-brother to Cornplanter. Also known as Sedwa’gowa’ne (“Our Great Teacher”), he was celebrated for his proselytization to the peoples of the Iroquois Confederacy, combining traditional Iroquoian morality with Quaker doctrines.[49] An alcoholic, Handsome Lake was subject to visions that empowered him to take the mantle of prophet and religious leader. His zealous moral code advocated temperance, the complete abstention from alcohol.[50] Handsome Lake died on August 10, 1815, in Onondaga County, near Syracuse, New York.

Not long after Handsome Lake’s death, an anonymous stoneware decorator one hundred and fifty miles away at the Israel Seymour stoneware manufactory in Troy, New York, made an elaborate memorial to the chief’s legacy, showing him with a sword and a shield emblazoned with a “T” for temperance. This well-rendered image (fig. 32) must have been derived from a period engraving, perhaps a political cartoon circulated at the time of his death. Today, the life and works of Handsome Lake are not much more than a footnote to American history except for Native communities and students of American religious history. Yet this utilitarian stoneware jug helps carry his memory forward.

Conclusion

Despite the gestural nature of the portrait, it is my belief that the decorator’s intent was to present an elegant and respectful image of a Native American man. The individual on the jug might be Little Beard, a notorious Seneca war chief who met an ignoble end after a drunken fight in an upstate New York tavern. His death date, 1806, is a close match to the suspected manufacture date of the jug. While we have no images of Little Beard, his name alone suggests a likelihood that he was known for facial hair.

Another candidate, in light of his widespread fame, is Joseph Brant, the “the most painted Indian” of his time. Brant, who died in 1807, had written about Native American facial hair and carried a powder horn on which are shown bearded Natives, although he did not wear a beard himself if his many portraits are reliable.

The death dates of both Brant and Little Beard fall within the suspected date range of the jug’s manufacture. It remains possible, however, that the image represents a much earlier historical event, as we have seen in the case of other commemorative ceramics objects. Even if the Native American depicted is never firmly identified, the jug remains a stoneware masterwork, and stands as the earliest American stoneware with a realistic portrayal of a Native American.

Even though the Manhattan jug was first published nearly a hundred years ago, its significance is still being explored. Its importance cannot be overstated, not only for the decorative arts field but for students of social and Native American history. A late-night social media posting had opened my eyes to histories that I had never fully considered—from ethnographies on Native American facial hair to the social history of Native American portraiture—histories that were captured in the social medium of decorated utilitarian stoneware by a Manhattan potter. Unlike the fleeting electrical impulses of our technological age, we can be confident that stoneware communications will continue to inform us for millennia to come.

I am indebted to Steve and Lorraine German of Mad River Antiques LLC (www.madriverantiques.com) for making the acquisition possible.

Skinner Auctions, American Furniture & Decorative Arts in Boston, sale 2145, June 9, 2002, lot 407, pp. 94 and 96. Marshall Goodman provided this reference for which I am most grateful.

W. Oakley Raymond, “Colonial and Early American Earthenware,” Antiquarian 9, no. 6 (January 1928): 41.

Edwin Atlee Barber, Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (1893; reprint, New York: Feingold and Lewis, 1976), p. 561; W. Oakley Raymond, “Remmey Family: American Potters, Part II,” Antiques 32 (1937), quoted in Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling, The Art of the Potter (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), p. 116; Arthur W. Clement, “New Light on the Crolius and Remmey Potteries,” American Collector 9 (1946): 10; Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African Burial Ground,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 41–66; William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Pottery of New York State, 1650–1900 (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987).

I am most appreciative to stoneware authority Timothy Bailey of East Nassau, New York, for his comments on the Manhattan and Albany stoneware decorators he has been studying.

John L. Scherer, Art for the People: Decorated Stoneware from the Weitsman Collection (Albany: University of the State of New York, 2015), pp. 22–23.

Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette F. Molin, “I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans,” https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/native/homepage.htm, published online February 22, 2018.

Laura Keim and David Orr, “Indian at Stenton: A Trail Left in Slip on a Redware Bowl,” in Ceramics in America, ed. Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), p. 297.

Kevin R. Muller, “From Palace to Longhouse: Portraits of the Four Indian Kings in a Transatlantic Context,” American Art 22, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 26–49.

Crocker Farm, sale, “Important BOSTON Stoneware Jar w/ Impressed Indian Motif, 18th century,” lot 2, March 14, 2015. For a discussion on Revere’s design, see Patrick M. Leehey, “Did Paul Revere Design the Massachusetts State Seal?,” Revere House Gazette, no. 132 (Fall 2018): 2–3.

The possible identification of the Native American depicted on the tavern sign is discussed by Peter Warwick and Leslie Warwick, “A Tavern Sign Revealed,” Antiques & Fine Art (Autumn 2014), available online at https://www.incollect.com/articles/a-tavern-sign-revealed (accessed September 21, 2019).

See Jacqueline Colleen Barber, “Face to Face: English Uses and Understanding of the Beard in Early Virginian Contacts,” master’s thesis, University of South Florida, 2008, available online at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7495/cdd12c62ae4a35a48975fc97cdc852ce4916.pdf_ga=2.180534823.165994420.1566397866-1957119943.1566397866 (accessed September 21, 2019).

Thomas Hariot, “A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia,” 1590, trans. from Latin by Richard Hakluyt, electronic edition available online at https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/hariot/hariot.html (accessed September 21, 2019).

“Observations Gathered Out of a Discourse of the Plantation of the Southerne Colonie in Virginia by the English, 1606. Written by that Honorable Gentleman, Master George Percy,” at www.virtualjamestown.org/exist/cocoon/jamestown/fha/J1002 (accessed September 21, 2019).

www.virtualjamestown.org/exist/cocoon/jamestown/fha-js/SmiWorks1 (accessed September 21, 2019).

William Strachey, The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612), ed. Louis B. Wright and Virginia Freund (London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1953), p. 56.

Bly Straube, “In Praise or Damning Caricature? An Early Seventeenth-Century Identification Badge,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal 10 (Winter 2010): 49–53.

Frank Waabu O’Brien (Moondancer) and Julianne Jennings (Strong Woman), A Cultural History of the Native Peoples of Southern New England: Voices from Past and Present (Boulder, Colo.: Bauu Press, 2007), pp. 25–30.

William Wood, New Englands Prospect, ed. Alden T. Vaughan (1634; Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977), p. 83 (eBook available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47082/47082-h/47082-h.htm).

Jennifer Evans and Alun Withey, eds., New Perspectives on the History of Facial Hair: Framing the Face (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Nelle Oosterom, “Kings of the New World,” Canada’s History 90, no. 2 (April/May 2010): 26–32 (available online at https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/first-nations-inuit-metis/kings-of-the-new-world).

William J. Buck, “Lappawinzo and Tishcohan, Chiefs of the Lenni Lenape,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 7, no. 2 (1883): 215–18.

Richard H. Saunders and Ellen G. Miles, American Colonial Portraits, 1700–1776 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Portrait Gallery, 1987).

More than 130 years later, an engraved portrait of Tishcohan was included in McKenney and Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Philadelphia: Rice & Co., 1870), with a notable enhancement of the chief’s black goatee.

William L. Stone, Life of Joseph Brant—Thayendanegea, 2 vols. (New York: G. Dearborn and Co., 1838). The definitive biography appears to be Isabel Thompson Kelsay, Joseph Brant, 1743–1807, Man of Two Worlds (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1984).

Milton W. Hamilton, “Joseph Brant —The Most Painted Indian,” New York History 39, no. 2 (1958): 119–32.

Gloria Lesser, “Iconography in the Portraiture of Joseph Brant (1742–1807),” master’s thesis, Concordia University, 1983.

Samuel Gardner Drake, Biography and History of the Indians of North America: From Its First Discovery, 11th ed. (Boston: Sanborn, Carter, and Bazin, 1857), p. 588.

I am indebted to Michael Galban, who shared the existence of this horn from his considerable archive of Native American resource materials.

The Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee, comprised six nations occupying large areas of New York State, up to the St. Lawrence River to today’s Montreal, and west of the Hudson River, through the Finger Lakes region.

Frank Wettenkampf, “How Indians Were Pictured in Earlier Days,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly 33, no. 4 (October 1949): 217.

Thomas S. Abler, Cornplanter: Chief Warrior of the Allegany Senecas (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2007).

Arch Merrill, Land of the Senecas (1949; reprint, Interlaken, N.Y.: Empire State Books, 1986), p. 116. O. (Orsamus) Turner, History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps and Gorham’s Purchase, and Morris’ Reserve . . . (Rochester, N.Y.: William Alling, 1851), p. 328 (“was one of the worst specimens of his race”).

Lockwood L. Doty, A History of Livingston County, New York: From Its Earliest Traditions, to Its Part in the War for Our Union: with an Account of the Seneca Nation of Indians, and Biographical Sketches of Earliest Settlers and Prominent Public Men (Geneso, N.Y.: Edward E. Doty, 1876), p. 100.

James Fenimore Cooper, “Account of the Dark Day of 1806,” Putnam’s Monthly Magazine (September 1869): 352–59. The eclipse has also been called Tecumseh’s Eclipse, after the Shawnee chief of Ohio who is said to have predicted it.

James E. Seaver, Life of Mary Jemison: Deh-he-wa-mis, 4th ed. (1824; Rochester, N.Y.: D. M. Dewey, 1856), pp. 139–40.

Doty, A History of Livingston County, p. 110.

North Star (Danville, Vt.), January 11, 1808, p. 3, col. 1.

Ellen G. Miles, “Saint-Mémin’s Portraits of American Indians, 1804–1807,” American Art Journal 20, no. 4 (1988): 2–33.

Howard C. Ric, Jr., “An Album of Saint-Mémin Portraits,” Princeton University Library Chronicle 13, no. 1 (Autumn 1951): 23–31.

Samuel Y. Edgerton Jr., “The Murder of Jane McCrea: The Tragedy of an American ‘Tableau d’Histoire,’” Art Bulletin 47 (December 1965): 481–82.

McCrea’s death is believed to have changed the course of the Revolution. After the murder, local settlers took up arms against the British in October 1777 and helped defeat Burgoyne in Saratoga. Meanwhile, patriots used the inflated story as propaganda to recruit soldiers and rally forces against the British. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/this-date-in-history-scalping-of-jane-mccrea-used-to-portray-natives-as-evil-kAcoAsVA-UKKMWcM2T2JxQ

I appreciate comments received from Jonathan O’Hea, Dan Mouer, and Steve Lalioff.

Scherer, Art for the People, p. 217.

Crocker Farm, auction, “Rare 3 Gal. Stoneware Jug with Mohawk Indian Decoration,” lot 284, March 23, 2019.

Dave Zirin, “You Can’t Unsee It: Washington Football Name and Quiet Acts of Resistance,” The Nation blog, September 5, 2014, https://www.thenation.com/article/you-cant-unsee-it-redskins-and-quiet-acts-resistance/. Dave Zirin describes the response of a young Native American girl after she saw the Washington Redskins logo on a media folder in his bag: she asked him why “the man’s head had been chopped off.”

Hirschfelder and Molin, “I is for Ignoble.”

Scherer, Art for the People, pp. 86–87.

Matthew Dennis, Seneca Possessed: Indians, Witchcraft, and Power in the Early American Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), pp. 53–80 (pt. 2: “Handsome Lake and the Seneca Great Awakening: Revelation and Transformation”).

The teachings of Handsome Lake were recorded in the nineteenth century and are still practiced by the Seneca as the Longhouse Religion. For the Code of Handsome Lake, see https://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/iro/parker/index.htm.