Pipe bowl, recovered from 44WM12, Westmoreland County, Virginia, 1647–1672. Earthenware. H. 1 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Brian Palmer.) Recovered from the Nomini Site, the “Angel Deer of Nomini” is arguably the finest artwork from the early Virginia colony. Algonquians commonly used this “Quadruped” motif. This thumb-sized example was created with a rectangular-toothed stamp, probably cut with European tools. Given the “Creole” nature of the colony, the only certain attribution is that the creator had Native American, or European, or African roots.

Pierre Pena and Mathias de l’Obel, Stirpium adversaria nova (London: Thomas Purfoot, 1571), p. 252. This is the earliest English print depicting tobacco being smoked. The caption states a palm leaf was used to wrap the weed.

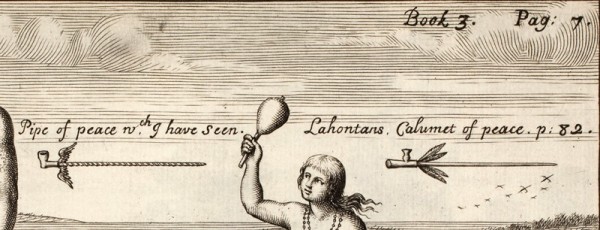

Engraving from Robert Beverly, The History of Virginia, in Four Parts, 2nd ed. (London: Printed for B. and S. Tooke, 1722), pt. 3, p. 145. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) Beverly’s History of Virginia provides a 1705 record of Native pipes with bowls attached to reed stems (calumet is a French word for reed). Beverly lived in the vast “Virginia” claimed by the Elizabethans, and he included excerpts from the Baron de Lahontan’s description of New France while basing this engraving on John White’s images of the Roanoke Island area. Carolus Clusius credited White’s 1585 expedition with carrying back the Indian pipes, which started the British clay-pipe industry.

Pipe bowl, Aquia Landing, Stafford County, Virginia, probably Late Woodland, ca. 1600. Earthenware. H. 2 3/16". (Private collection; photo, Laura Powell Kiser.) This bowl, with its reed stem long since vanished, belongs to a ceremonial pipe of the Patawomeck people. A horizontal band of chevrons is faintly visible below the rim, while its ringed surface hints of Iroquoian style in the Algonquian world. A storm revealed this pipe in 1997, whereupon it was returned to the care of a Patawomeck chief.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44PG51, Prince George County, Virginia, ca. A.D. 1300 or earlier. Earthenware. H. 1 3/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) In the mid-Atlantic United States, the earliest known smoking implements are tubes. Some later types had one end closed down to a small hole for sucking out the smoke. In one variation, that tapering end grew into a stemmed “elbow” pipe. Although shattered, most of this pipe was recovered, implying it may have been ritually destroyed, or “killed.”

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44BO3, Botetourt County, Virginia, probably Late Woodland, ca. 1600. Earthenware. H. 1 1/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This pipe probably dates to the Late Woodland, before the arrival of English colonists, and was excavated from a possible Siouan site many miles inland on the Roanoke River. This Native form is believed to have served as the prototype for the very first English pipes, rounded “belly” bowls, which appeared in the 1580s. The origin of the English clay-pipe industry is credited to a 1585 expedition which may have traveled up the Roanoke River as far as today’s Roanoke Rapids.

Pipe bowl, probably London, ca. 1607–1610. Earthenware. L. 2 3/4". (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation [Preservation Virginia]; photo, Michael Lavin.) Excavated from the 1610 well of James Fort, this “belly” bowl is one of the very first European clay tobacco pipes, made for smoking the expensive new “miracle drug.”

Tobacco pipe, Robert Cotton, Jamestown, Virginia, ca. 1608–1610. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery [Preservation Virginia]; photo, Michael Lavin.) These were made at James Fort by Robert Cotton, the very first Anglo-American pipe maker. Cotton may have been a London-trained pipe maker, but he did not use a European-style mold in Virginia. These hand-built works are statements of cultural fusion, an Algonquian-style elbow bowl turning into an octagonal stem that goes round, like a European musket barrel.

Pipe, recovered from 44PG302, Prince George Country, Virginia, ca. 1619–1635. Earthenware. H. 1 1/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Excavated from Cecily Jordan Farrar’s well at Jordan’s Point on the James River, this was probably made by a Siouan speaker. It has the typical undecorated stem of a Native pipe, with Algonquian-style bands stamped around the bowl, along with a single hanging triangle. The stamp had rectangular teeth, possibly cut with European tools. Traces of white infill make this one of the two earliest datable examples of that decoration. Elizabeth Bollwerk most often found sculptural elaboration and inverted rims on Iroquoian and Siouan sites, but acute carination is more typical on sites believed to have been Siouan.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44SK56, Suffolk, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. H. 1 7/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Although found in Suffolk, an Algonquian area, this was probably made by an Iroquoian speaker. “Ring” bowls with impressed surfaces are common in the northeastern U.S., but relatively rare south of Pennsylvania.

Tobacco pipe stems, Bookbinder, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Taft Kiser.) The remarkably strict decorative grammar of Bookbinder pipes makes it almost certain they were the products of a single individual. That person apparently lived in Virginia Beach, and may have been trained as a pipe maker in Britain or the Netherlands.

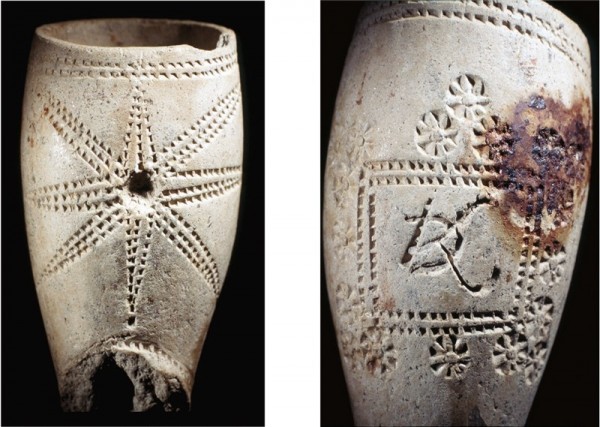

Pipe bowls, recovered from 44CC178, Charles City County, Virginia, ca. 1640. Earthenware. H. 1 5/8". (Courtesy,Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) Large stamped stars are the most common motif found on local pipes in the lower James River drainage. The type probably originated in Charles City County as a venture of Walter Aston. Workers at Aston’s house created distinctively colonial pipes, molding an Algonquian form adjusted toward European tastes.

Tobacco pipe, Star Maker school, ca. 1640. (Courtesy, Colony of Avalon Foundation; photo, Jim Tuck and Barry Gaulton.) Archaeologists excavated this star bowl, monogrammed “DK,” in Canada from a building associated with Newfoundland’s governor Sir David Kirke. Made in Virginia at the Walter Aston site, the excavation of that production center recovered a bowl fragment with the same “DK” monogram.

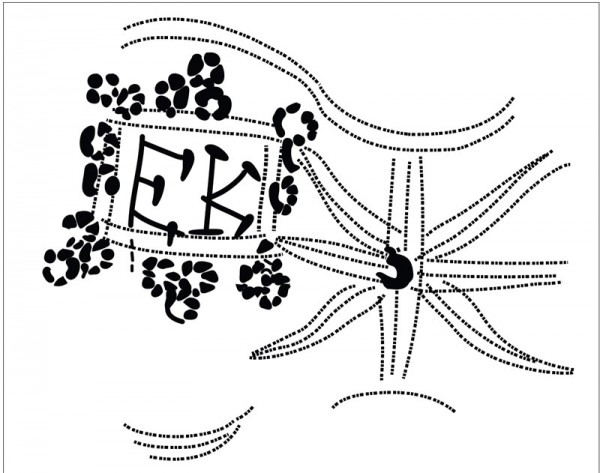

Drawing of a tobacco pipe, recovered from 44CC178, Charles City County, Virginia, ca. 1640–1667. (Artwork by Wynne Patterson.) Martha McCartney searched the records associated with Walter Aston but did not find a possible identification for the “EK” stamped on this pipe. It seems likely that Aston’s star pipes decorated with initials were presents for business associates.

Dish, Harlow, Essex, England, dated 1632. Metropolitan slipware. D. 13 7/16". (Courtesy, Museum of London; site code CEH12, context [105]; photo, Andy Chopping.) European slipwares seem to be the most logical inspiration for stamped decoration filled with white clay, which appears ca. 1620. Dishes such as this may also have served as samplers inspiring colonial pipe makers. Native artists appear to have followed traditional patterns, but colonials new to the craft had to invent their own decorative grammars.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44WM12, Westmoreland County, Virginia, ca. 1647–1679, Earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This bowl, possibly decorated using a shark’s tooth, shows the stamped horizontal bands often used in Algonquian decoration. It may have been made by a Matchotic working for the colonists living on the Potomac’s Nomini Bay. Overall this is a typical Algonquian elbow pipe, but the carinated rim hints at Siouan or Iroquoian influence.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44VB48, Virginia Beach, Virginia, ca. 1640–1680. Earthenware. H. 1 15/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) This Running Deer pipe, rotated to show the decoration, matches a pipe found in the Netherlands. Both belong to a group of eight known bowls called “Quadrupeds with ‘Knees,’” which may come from the Delmarva Peninsula. Those eight show variations, but all have bent legs drawn with eight or twelve stamps—the Quadruped motif typically used four straight lines. Two of the Knees group also depict male deer with antlers—the only branched antlers on all of the known Quadruped pipes.

The wife of a “werowance” (chief of Secotan), leaf from a volume (now consisting of 113 leaves of drawings) associated with John White, 1585–1593. Watercolor on papers. (British Museum, SL,5270.5.) This woman “of Secotan” exhibits decorated Algonquian elbow “pipes” on her flesh. The geometrical designs used on Native pipes are probably traditional patterns adapted from weaving, or pottery, or tattoos such as this.

Pipe bowl, recovered from 44JC39, James City County, Virginia, ca. 1650. Earthenware. H. 1 9/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Katherine Ridgway.) The pipe shown here looks like a classic bowl from Bénin, but was almost certainly made in Virginia. The form originated with American Indians and appeared in Africa at roughly the same time as tobacco, about 1600. This bowl probably was made a few miles below Jamestown and belongs to an intriguing group of carved pipes generally confined to the James River drainage.

Tobacco pipes, Emanuel Drue, Maryland, ca. 1660–1669. Earthenware. Top: Drue Type B, belly bowl. Center: Drue Type A, angular elbow. Bottom: presentation “Crumm Horn” pipe. (Courtesy, Anne Arundel County, Maryland; photo, Al Luckenbach.) Emanuel Drue made the two classic forms of seventeenth-century English America, the European-style belly bowl, and the Algonquin-style elbow. His elbow pipes include Bookbinder school pipes, and he was the only other maker to produce agated and marbled surfaces. Drue also molded European-style belly bowls in white clay, and made more challenging pipes like the Crumm Horn.

Pipe bowl, found in Schermer, North Holland, ca. 1640–1680. Earthenware. H. 1 3/4". (Photo, Ewout Korpershoek.) Probably made on the Delmarva Peninsula, this is one of only two seventeenth-century American tobacco pipes known to have been found in Europe. One of the Quadrupeds with “Knees,” this was almost certainly decorated by the same person as the Virginia Beach find, illustrated in fig. 17.

Archaeologists working in the Anglo-American colonies occasionally discover particularly wonderful objects of unknown art. Excavators have uncovered thumb-sized red or tawny clay tobacco pipe bowls, locally made and stamped with geometric bands, stars, or the enigmatic “Quadruped,” better known as the “Running Deer” (fig. 1).

Practically unnoticed by records, these pipes are found only within archaeological contexts. Museums curate intact seventeenth-century Westerwald stoneware, Ming porcelain, and even clothes like those worn by Captain John Smith, but tobacco pipes are an example of “small things forgotten”—quickly made, used, broken, and thrown away as garbage centuries ago—but in such objects and their tiny details, scholars have unearthed stories of our ancestors and how they adapted in the constantly changing world.[1] Pipes were trade goods, and one theme of this essay is the merging of diverse characteristics by pipe makers applying their arts. This increased as tobacco became an international economic engine.[2]

History of Smoking Pipes

Tobacco pipes are essentially hollow tubes that probably originated from the Mayan sikar (“to smoke rolled tobacco leaves”), the ancestors of modern cigars (fig. 2).[3] British mariner John Cockburn smoked -“Seegars . . . Leaves of Tobacco rolled up in such Manner, that they serve both for the Pipe and Tobacco itself.” He added, “there is no such thing as a tobacco pipe throughout New Spain, but poor awkward tools used by the Negroes and Indians.”[4]

Cockburn was wrong; sites in the South do have pipes, and sometimes with intriguing similarities to later Northern bowls.[5] The earliest-known pipe in the mid-Atlantic United States, a stone tube made roughly four thousand years ago, was recovered in what is now the state of Tennessee.[6] These open tubes were still in use when the Europeans arrived, but they were less popular than those which tapered down to a stem with a tiny hole to draw out the smoke.

There are two types of stems: one is an integral part of the bowl, the other is an attached “reed.” With the former, the bowl’s material can be worked out into a stem but its length is limited. Having a bowl and attaching a reed, however, permits stems of exceptional length and artistic expression (fig. 3).

The Native Americans met by European colonists often smoked reed pipes for ceremonial purposes, and size mattered: John Smith’s description of a Susquehannock man included that “his Tobacco pipe 3 quarters of a yard long, prettily carved with a Bird, a Beare, a Deare, or some such devise at the great end, sufficient to beat out the braines of a man.”[7]

Because of their use in ceremonies, reed pipes are the type most often described and illustrated in contemporary literature, but they are almost invisible in the archaeological record in the regions of today’s mid-Atlantic states. Elizabeth Bollwerk, after examining 1,024 Native bowl fragments dating between A.D. 900 and 1665, classified only twenty as fragments of reed pipes (fig. 4).[8]

Natives also carried more compact smoking implements. Well-defined bowls tapering out to clay stems and bent like an elbow are known from the Early Woodland (fig. 5). These one-piece elbow pipes “became the most common form of smoking implement from the eleventh century A.D. onward in eastern North America.”[9] Although they were relatively simple elongated cones of clay, their makers discovered that they were creating something valued by other Natives and, later, European colonists. Describing those Natives producing trading goods in 1709, John Lawson noted, “those that are not extraordinary Hunters, make Bowls, Dishes, and Spoons, of Gum-wood, and the Tulip-Tree; others where they find a Vein of white Clay, fit for their purpose make Tobacco-pipes. . . .”[10]

Clay-Stemmed Elbow Pipes

Clay-stemmed pipes are found in a roughly triangular zone with its northwestern corner west of the Great Lakes, then east to the Atlantic, and down the coast to the Carolinas.[11] Across that broad area, the primary linguistic groups were, roughly, Iroquoian in the north, Siouan on the west, and Algonquian in the southeastern Coastal Plain.

Data on the linguistic groups is fragmentary. In almost every case, the records date only after European colonists had decimated the Native cultures. Buck Woodard, Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, and Stephanie Hasselbacher described a sample of words collected in 1716 at Occaneechi, a major town on the Roanoke River near the North Carolina border. Occaneechi had strong ties to the Saponi-Tutelo and was almost certainly Siouan, but they found that, in fact, “the majority of recorded numbers are Algonquian, some words Siouan, and a scattering of Iroquoian is present.”[12]

Distinctive pipe forms tend to come from Native sites in differing linguistic areas but there is often overlap of styles. Pipes were trade goods. Pipes commonly identified as seventeenth-century Algonquian in style generally have elongated cone elbows, often with stamped decoration on the bowls. This stamping can cover the junction with the stem, but seldom continues toward the mouthpiece. Decorating tools are easily improvised from shark’s teeth, bones, reeds, and other objects. Called “Chesapeake” pipes by Matthew Emerson, they are the most common type on the Coastal Plain from Delaware to the Carolinas.[13]

That coastal region was occupied primarily by Algonquin speakers, but tributaries of the Albemarle Sound had pockets of Iroquoian Tuscarora and Siouan Saponi-Tutelo.[14] Iroquoian pipes tend to be more sculptural, with impressed rings, flaring bowls, or, most famously, effigies of people or animals. Stems curve, unlike Algonquian pipes, where the stem runs straight to the bowl.[15]

It is difficult to identify Eastern Siouan pipes because many of the sites believed to be Siouan became refuges for other Natives driven from their land by European colonists.[16] Assemblages tend to blend Algonquian-style elbow bowls with sculpted forms more typical of the Iroquoian neighbors.

Rise of the Seventeenth-Century American Clay-Stemmed Pipe

In the late sixteenth century the English began inserting themselves into this landscape.[17] Columbus’s men had carried tobacco back to Europe, and the English accidentally landed where the most common means of ingesting nicotine was the clay-stemmed elbow pipe. Cataloging tobacco in a book published in 1605, botanist Carolus Clusius mentioned the 1585 Roanoke Island expedition sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh and the birth of the British pipe industry.

The colonists reported that the inhabitants often used certain pipes made of clay to take in the smoke of burning tobacco. The English, upon their return from there, brought with them similar pipes for taking tobacco smoke. Thereupon the use of tobacco spread even throughout the whole of England, especially among the courtiers, with the result that they saw to the manufacture of many similar pipes for the inhalation of tobacco smoke.[18]

The new English bowls were rounded like a full belly and made in brilliant white clay, resembling a small onion. The Native prototypes of these “belly” bowls were shipped from an Algonquian-tradition region, but after looking at the pipes recovered in that area David Givens has noted that belly bowls most resemble pipes from probable Siouan sites farther inland (figs. 6, 7).[19]

English adventurers were also on the payroll of the Dutch States General, fighting the Spanish in the Netherlands. Cross-Channel exchanges by these mercenaries, religious refugees, and others carried London’s new craft of pipe making to the Netherlands at the beginning of the seventeenth century.[20] The classic white belly-bowl pipe seen in Dutch genre paintings is an adaptation of an English pipe, in turn adapted from an Indian pipe.

About twenty years after the birth of the English clay pipe, the British erected James Fort in the Algonquian Paspaheigh territory. “Tobacco-pipe-maker” Robert Cotton arrived in 1608; research by Givens indicates that Cotton had probably earned the title by having served as an apprentice to a London pipe maker. Cotton’s record in Virginia, Givens writes, is limited to the single entry for his arrival and the trays of archaeologically recovered pipe-making debris attributed to him (fig. 8). Remarkably, Cotton did not produce English pipes. He made colonial pipes, combining indigenous traditions with English.[21]

English pipes were being molded by 1590, but analysis of Cotton’s work shows he did not use a mold. Exhibiting a mastery of materials, he worked with a knife, a wire, and a flat surface to blend Algonquian-style elbow pipes with European characteristics.[22]

Cotton proves how archaeological research can recover “small things forgotten.” America’s first European-born pipe maker was just a name on a list until 1994, when Jamestown Rediscovery archaeological curator Bly Straube spotted the unusual clay fragments and began corralling them on a lab tray.[23] Cotton’s endeavors now help illuminate Jamestown and its settlers.

Cotton likely spent years in London training as a “Tobacco-pipe-maker,” and arrived with exceptional skills and a repertoire of the latest European technology. He may or may not have had the most basic but expensive tool of his trade, a European mold for English “belly” bowls. If he had wanted to make European pipes, it seems certain that someone in James Fort could have carved a wooden mold. Instead, Cotton adapted.

In the Cotton years, before 1611, the English were not yet growing tobacco, and pipes were scarce in James Fort.[24] Most of the American pipes appear to have been made by Cotton. A small number appear to be Algonquian, which have elbows with robust stems about four inches long, and several of the bowls have typical Algonquian stamped decoration.

Despite Robert Cotton’s production and the tobacco boom after 1616, imported European pipes predominate on 1620s–1630s Virginia sites like Jordan’s Point (44PG300, 44PG302, 44PG307).[25] Colonists were taking Native land as they moved up the tidal rivers toward the fall line. Native bowls are present in small numbers, and while there are coastal Algonquian types, there are also bowls that may be Iroquoian or Siouan, from more distant regions (figs. 9, 10).

The dominance of European pipes at the far frontiers of Virginia in the 1620s and 1630s is unexpected and an interesting anomaly. Archaeologists hunt anomalies because they can reveal new things—like the pipe-making debris in 1608–1610 contexts, years before Europeans grew tobacco in Virginia. By the 1620s, Virginia was tobacco-mad, and even though a smoker could be satisfied with a corncob and a reed, colonists continued to use smoking implements transported thousands of miles from across the ocean. Over the next 150 years, European clay-stemmed pipes became increasingly delicate and awkward but nevertheless continued to hold a place at the centers of the colonies. It seems probable that the bright white bowls, despite associated costs, gave colonists a concrete reminder of their European roots.

The Maryland Colony was established in 1634. Very soon after, circa 1640, colonial pipe makers were common in the Chesapeake region; it seems certain that by then pipe makers had also begun working in New England. This was a time when the British people were rebelling against the monarchy and British merchants were less active in supplying the colonies.[26] Colonists had relatively few manufactured goods, including pipes, but they did have clay and fuel. The appearance of the craft shows they also had the third critical ingredient, labor. These new colonial American pipe makers almost certainly included women, who are well documented in the craft by contemporaneous European records.[27]

In addition to mold-made elbow pipes, called “export” pipes in New England, American producers introduced mold-made European-style “belly” bowls. Produced in Virginia and Maryland in local red or terracotta colors, they usually are found on sites near salt water, and often seem associated with Puritans. In New England, excavations of seventeenth-century sites in Boston recover so many red belly bowls that it seems almost certain they had been made nearby. Emerson Baker notes the two styles—“both large belly bowl and export pipe” (elbow)—were used in both English and French settlements of New England, particularly in contexts of 1650 to 1675.[28] Richard Veit and Charles Bello report mold-made red “export” (elbow) pipes in Pennsylvania, along with a 1685 reference to pipe making there or in New Jersey.[29]

American belly bowls used local clays, but they were finished in exactly the same way as English ones, unmarked except for a milled band around the bowl rim. Sometimes there is a maker’s mark on the heel, but further marking on English pipes is exceptional until the later seventeenth century. The Netherlands also produced white clay belly bowls similar to the British pipes, although Dutch pipes often had maker’s marks. Dutch stems were sometimes covered with geometric stamping, a significant detail.

The best-known American belly bowls are marked “RP,” linked to the documented maker Richard Pinner by author Luckenbach in 2006. Luke Pecoraro found Pinner pipes in frequent association with sites tied to the Gookins, a family of Puritan merchants. The Gookin connections included the property associated with the Chesopean site (44VB48), the suggested location for the production of the pipe type called the “Bookbinder.”[30]

The Bookbinder was originally designated “Type G” in 1979 by archaeologist Susan Henry (fig. 11). A few years later, author Kiser began making notes on the pipes, most remarkable for intricate stamps that often used clays swirled red and white like marbled book endsheets. They seemed to be in almost every Chesapeake collection viewed by Kiser in the 1980s, and after master craftsman Bill Ruppert pointed out the stamps were probably bookbinding tools, the pipes became known colloquially as “Book-binders.” Henry’s research shows they are molded and found only inside the colonies, not on Native sites still beyond European control. Emerson called them “Type 3,” and stated they probably were the products of a single maker who was Dutch or English.[31]

The repetition of the stamping makes it seem certain Bookbinder was a specific maker. Removing the abstraction of the “Type G” and “Type 3” categories and adding a touch of Deetzian humanism with the identifier “Bookbinder” was a small thing, but one that reinforced the artistic choice and skills of pipe making.[32] When the authors Luckenbach and Kiser began looking at pipes across the region, that change proved to be a key shift of paradigm. Thinking of Bookbinder as a person rather than an abstract organic element in an indistinct craft process put the focus onto the individual.

Bookbinder molded the same pipe and used the same stamps in the same places time after time, getting into a groove and making the same basic pipe, over and over, hundreds or thousands of times. When other pipe makers created batches of bowls, they probably did likewise, that is, dropped into a groove and made similar pipes. It is a small thing, yes, but a solid portal for research.[33] All pipes have a home, and a range, and a maker.

Bookbinder’s workshop appears to have been at the Chesopean Site (44VB48) in Virginia Beach. Lauren McMillan’s work indicates the maker was active only in the 1640s, when Chesopean was the home of Sarah Offley Thoroughgood Gookin.[34] Her second husband, John Gookin, was the son of a Puritan merchant family with international ties.

Bookbinder used a European-style mold to produce Indian-style elbows with Dutch-style decorated stems. English Puritans often lived in the Netherlands before continuing to America, where many settled in the Virginia Beach area. McMillan suggests Bookbinder might have been “a Dutch immigrant or English Puritan who learned his or her craft while in exile in the Netherlands.”[35]

The consistency in the production suggests a school of makers using local clays and improvised versions of Bookbinder stamps to copy Bookbinder’s grammar.[36] Those copies reached the Jamestown area, but McMillan notes that 73 percent of the Bookbinder school pipes come from Chesopean, the probable site of Bookbinder’s workshop.[37]

Like Bookbinder, pipe production at Walter Aston’s house probably started in the 1640s and may have lasted until 1667 (fig. 12). Located on the James River below its confluence with the Appomattox River, Aston’s shop was almost certainly the largest producer of “star” pipes in seventeenth-century Virginia. Emerson noted that these bowls, stamped with large stars, have been found primarily in the James River drainage.[38] Isolated examples are recorded from Newfoundland down to North Carolina.

Martha McCartney discovered that in 1634 Walter Aston bought land below Shirley plantation, and lived in that area until his death in 1656. The compound apparently was abandoned after the death of his son, Walter Aston Jr., in 1667.[39]

Walter Aston had a variety of enterprises and international ties.[40] Aston displayed his wealth, living in a house with a tiled brick cellar when most colonists did not have a brick fireplace. Martha McCartney found Aston’s ventures included acquiring a 1641 license to explore “west southerlye from Appommattock River.”[41] This is essentially the route of today’s Interstate 85 to the site of the seventeenth-century Native town Occaneechi, where archaeologists have recovered star pipes as well as another motif found in Aston’s group, a vertical strap filled with punctuates.[42] Records are sparse on Aston’s labor force, but McCartney documented Irish indentured servants and enslaved Blacks.[43] Aston might have enslaved American Indians as well.[44]

The pipe group from Aston’s shop includes 120 local bowls, 65 of which are star pipes.[45] Aston probably had an experienced pipe maker, but the diversity of the decorations indicates the group of pipes was made by multiple people.[46] Requiring relatively light labor, pipe making was probably a welcome change from the fields and arguably one of the best jobs for pregnant women, the enslaved elderly, and other vulnerable groups.

Aston’s “star-and-panel” style often have letters within the panel, and among the wasters is a fragment marked “DK” (fig. 13).[47] A matching monogram has been found in Canada at the probable home of Sir David Kirke, governor of Newfoundland.[48] Kirke’s international ventures are known to have included Spanish wine, and it seems likely he was also involved in the trade of Newfoundland fish for Virginia tobacco.[49] The pipes bearing Kirke’s monogram are physical evidence of a connection to Virginia, probably a 1640s commercial relationship with Aston. It seems likely the pipes were sent as gifts rather than merchandise.

Aston’s shop had at least three custom molds; they probably were made in the 1640s, although the pipes they produced look more eighteenth-century in size and form (see figs. 12, 13). Based on examples recovered at nearby Flowerdew Hundred, it appears Aston’s molds were being used there after the hurricane of 1667.[50]

For archaeological evidence of pipe making, the best collections are associated with Robert Cotton, the 1660s Maryland maker and Puritan planter Emanuel Drue, and the “Nomini” site (44WM12), on the Virginia shore of the Potomac’s Nomini Bay. Lauren McMillan and Brad Hatch have determined that the Nomini pipe maker was active between 1647 and 1679 (fig. 16).[51]

Emanuel Drue clearly used European-style molds and other technology, but the Nomini pipes seem to reflect traditional Algonquian techniques. The significant difference is that the European-style process used molds; in the shops of Drue and Walter Aston, they stamped out clay and inserted tools. At Nomini, they created clay tubes and shaped the ends. Because the Nomini pipes are Algonquian-style elbows with Algonquian-style decoration, the Nomini pipe maker is believed to have been an Algonquian, possibly one of the Matchotic originally living on the land.[52]

McMillan’s analysis of the archaeological data demonstrates that Nomini bowls were being made inside a colonial compound, but the collection appears to be the most tightly dated, extensive group of seventeenth-century Native American pipes in the region.[53] Nomini bowls are tall, cylindrical elbows, usually with a faintly inverted rim. Rather than being characteristic of this workshop, the form is widespread and appears to be a typical Algonquian trade bowl of the third quarter of the seventeenth century (fig. 17).

Some Nomini bowls have a well-defined carination at the top—an inverted rim. Bollwerk found inverted rims most commonly on Iroquoian and probable Siouan sites.[54] Nomini stems can have an exceptionally glossy finish, but they follow the general rule for Native pipes—bowls are decorated, and the stamping can cover the junction at the bottom. There is typically no decoration on the stem, toward the mouthpiece.

Nomini bowls usually have a stamped band at mid-girth, typical on pipes believed to be Algonquian, which often use such bands to partition the surfaces of the bowls. Decoration is most often above that mid-girth band. The patterns used at Nomini are geometric forms relatively universal to Algonquian pipes, which might have been adapted from those used in weaving, pottery, or tattoos. Nomini’s decorators used circular stamps like reeds or bones and other traditional tools, almost certainly including shark teeth. Stamps with rectangular teeth, probably European-style combs cut with steel blades, also appear (see figs. 1, 16, 18).

The most common motif from Nomini is the Quadruped, or Running Deer. As is typical—part of the enigma of the motif—the creature is stamped in differing ways, implying multiple decorators at Nomini. One of those individuals apparently produced the futuristic “Angel Deer of Nomini” (see fig. 1).

Like Aston’s shop, Nomini seems to have been a side venture of a large planter. McMillan’s research shows Nomini was occupied about 1647 by Thomas Speke and his first wife, Anne, who died about 1655. His second wife, Frances Gerrard, outlived three more husbands after Speke, who died in 1659. A 1659 deed reference to the “Indian field commonly known as the Pipemaker’s field” implies that the Spekes had a cooperative relationship with a pipe maker. Speke was exceptionally wealthy, and his probate inventory indicates that at the time of his death he held legal title to three other human lives: Tom, Mary, and Frances, each of whom is listed simply as “negroe.”[55]

The participation of enslaved West Africans is the most debated topic concerning seventeenth-century American pipe making. All period documents about pipe making were generally written by Anglo-American males, and all of the colonial records show pipe makers as Anglo-American males or Natives of both sexes. Dan Mouer’s “Chesapeake Creoles” describes a much richer seventeenth-century landscape, populated by European, African, and Native American men and women.[56] First and foremost, the colonists were farmers, accustomed to working together. If there were pipes to be made, the workers probably shared the tasks.

The debate comes from Matthew Emerson’s attempt to credit a great deal of the pipe art to West African antecedents.[57] That broad attribution was rejected by specialists who found his evidence inadequate, and objected to his dismissal of the almost 4,000-year-old Native craft.[58] Regardless, it seems logical that some captive Africans did make American clay pipes, and perhaps future researchers will be able to identify examples (fig. 19).

In seventeenth-century colonial America, the enslaved often included both Africans and Natives.[59] Enslaved workers almost certainly made the elbow pipes used in Jamaica between about 1680 and 1730. Apparently rolled out as clay tubes like Nomini pipes, they are undecorated except for occasional raised spurs and possible maker’s marks. These are believed to be the “Negro” pipes referenced in period records.[60]

Of seventeenth-century American clay pipes there are essentially no period records; almost everything “known” comes from archaeologists interpreting findings. But in 1991, author Luckenbach was shown artifacts collected by Bob Ogle at Swan Cove, once part of Maryland’s 1649 Providence settlement on the Severn River. Following up, Luckenbach’s team excavated evidence of a 1660–1669 cottage industry undertaken by Emanuel Drue, providing the most extensive evidence on the craft as it was practiced in America. Drue’s estate was inventoried in 1669, his pipes are identified, and his compound has been archaeologically excavated (fig. 20).[61]

Evidence, such as river cobbles subjected to enough heat that they glazed, shows a European-style industrial kiln once existed at Swan Cove, patterned on contemporaneous kilns in England.[62] This up-to-date structure was typical of Drue; the Swan Cove excavations illuminated the importance of style to early pipe makers in the region. Drue’s probate inventory, taken after his death in 1669, lists two brass pipe molds. Based on his pipes, one was an English-style belly bowl and the other was an Indian-style elbow—the two classic forms of the English American colonies in the third quarter of the seventeenth century.

Drue followed current style; the European belly bowl form was seldom decorated, except for milling around the rim. Indian bowls were often decorated, and Drue’s elbows often have such stamping, but not always. It seems likely that Drue was trying to please two different customer bases.

Presumably Drue’s main occupation was tobacco planter, like that of his neighbors, but his use of industrial production methods clearly indicates an extensive knowledge of the British craft. Even though he no doubt sought profit, he went to the added expense of making his own custom stamps and put extra effort into the decoration. Records show he was a Puritan, and it is possible he once lived in the Virginia Beach area. It seems certain he knew Bookbinder pipes. Although working over a decade later, Drue was essentially a member of the Bookbinder school, molding elbow pipes with stamped decoration around the rims. Drue went further, though, traveling far enough to find “gourmet clays” of different colors for the manufacture of his pipes. Only two seventeenth-century American pipe makers are known to have agated and marbleized pipes: Bookbinder in the 1640s, and Drue in the 1660s.

While essentially all seventeenth-century American clay pipes are terracotta, one surprise is that Drue found pure white clays, and when he used them with his belly-bowl mold, the result was virtually indistinguishable from English pipes. This provides a cautionary tale for archaeologists who have uniformly considered white pipes to be imported.

In addition to his standard shapes, elbows and belly bowls, Drue produced elaborate presentation pipes. His “Crumm Horn,” named after a parallel produced in Holland, is the most distinctive seventeenth-century colonial American pipe in existence (see fig. 20). A total of 94 different hand decorations were applied, using three different tools, one of which was recovered from the site.

Decline of the Seventeenth-Century American Clay-Stemmed Pipe

Drue died at the end of a decade of great transition. The English monarchy regained control in 1660, and the Dutch began to fade away in the Americas, losing New Amsterdam in 1664.

The Netherlands had helped plant Virginia. In the colony’s first decade, the Dutch allowed English mercenaries like Sir George Yeardley to leave their companies in the Netherlands and join the Virginia adventure. The States General paid Sir Thomas Dale for his five years in Virginia, 1611–1616.[63] Britain’s later political upheaval left a major vacuum, stranding American tobacco in its barns and presenting opportunities for the Dutch: analyzing Potomac River sites occupied between 1630 and 1664, McMillan found the European pipes to be 95 percent Dutch.[64]

Despite the Dutch reputation as colonial traders, there is strong evidence they did not trade in American-made pipes. The merchants operating in the Chesapeake also visited New Amsterdam, but American pipes are essentially unknown on Dutch colonial sites.[65] The authors are aware of only one seventeenth-century American-made pipe found in a Dutch context, apparently a sailor’s souvenir (fig. 21).[66] It is a striking anomaly that the Dutch took American tobacco but not American-made tobacco pipes. Another random but possibly related point is that in the early English Chesapeake, in general only Indians decorated pipe bowls, whereas only the Dutch decorated stems. But when colonials began making pipes about 1640, they made two types, very plain English-style belly bowls and Algonquian-style decorated bowls with Netherlandish decorated stems.

The Dutch did not distribute American pipes; it seems likely that local demand absorbed local production. Pipes found outside the Chesapeake region, like those of Sir David Kirke and the Schermer Quadruped, probably reflect relationships rather than mass sales of pipes. It does appear that the products of a few makers, like Bookbinder, were shipped around the region. Luke Peroraro used Richard Pinner’s European-style belly bowls to sketch a network of Puritan traders moving goods in the Chesapeake.[67]

Some time after about 1660, however, as pipe making expanded in northwestern Europe, its colonial counterpart faded away, ending by roughly 1680. Almost certainly, the major change came in London, where the biggest event was the restoration of the monarchy. The death knell of the American craft might have been as simple as a steady flood of inexpensive British pipes.

Outside the strict control of Europeans, the Native Americans continued making clay-stemmed pipes into the eighteenth century. Neoheroka Fort in eastern North Carolina was built in 1711 during the Second Tuscarora War and destroyed in 1713. There, Dane Magoon found typical pipe forms—elbows, “onion,” and “ring” types—but also examples reflecting European belly bowls. Evidence from Neoheroka Fort has suggested that Native pipe makers retained traditional traits while also reflecting new influences.[68]

Even among the Natives, the manufacture of American clay-stemmed pipes essentially ceased in the early eighteenth century. Long-stemmed white ball clay British pipes continued pouring into the colonies, but the more practical bowl and reed style eventually took over.

Conclusion

Of all the motifs associated with pipes, the Running Deer is perhaps the most puzzling. The stamped quadruped appears to be a deer, or usually a pair of deer chasing each other. Antlers are exceptionally rare, and the species is debatable. Possible alternatives include dogs, horses, foxes, rabbits, pigs, and goats. Typically they are depicted with the erect tail characteristic of running white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).

The Running Deer motif is almost certainly Algonquian in origin, but dating evidence is incomplete on the earliest examples.[69] Bollwerk’s recent reevaluation notes that they are found in the mid-seventeenth century.[70] Running Deer pipes are very common between the 1640s and 1660s, and, while excavated in Virginia, most are found in coastal Maryland.[71] This distribution supports the interpretation of Running Deer as an Algonquian motif. Virginians were expanding their colony by dislocating the Algonquians of the Coastal Plain in this period. Maryland, established in 1634, still had powerful Algonquin-speaking groups to its north and east.

Questions about the motif include how and why it suddenly appears in many places about 1640. The variations in execution of the motif point to multiple individuals doing their own interpretations rather than following a traditional pattern.

Variation is visible even in the best-defined group (currently eight known bowls), called Quadrupeds with “Knees.” The animals usually face left, but in the Knees group, half of them face right. Two bowls in this group clearly depict male deer, as they have the only known branched antlers.[72] The production site is unknown. Two have been found on the Eastern Shore at Eyreville, three were recovered from sites below Jamestown, and one from Saint Mary’s City. The last American find was excavated in Virginia Beach at Chesopean, believed to have been the home of Bookbinder. The eighth example comes from the North Holland village of Schermer, near Alkmaar. Scholar Bert van der Lingen described this as “a unique discovery,” notable as the only pipe of this type found in the Netherlands.[73] The major anomaly with the Quadruped, or the Running Deer, motif is its sudden appearance from multiple Native sources. The easiest explanation is that they were simply popular, like the Dutch-style stems. They are usually running and, as art, tend to be joyous. Their widespread appearance implies the motif had more universal importance to the Indians making pipes for colonists, however. Perhaps the creatures were usually meant to be dogs, with some unknown ritual significance.

Half a century after James Fort was erected, colonials were smoking using either a variant of Indian elbows or the belly bowl, also Indian, which became a symbol of northwestern Europe. The elbows were decorated in Dutch and/or Indian style, whereas belly bowls generally kept the same rigid British grammar, being absolutely plain except for milling around the rims. Local makers like Cotton and Drue produced American adaptations embracing the swirling cultural stew of the colonies, although some people apparently still preferred the more formal structure of British pipes.

Local pipes remain fascinating because almost all of the information we have about them—including their very existence—comes from excavations over the last century. The Quadrupeds with “Knees” were not found until the final stages of editing this essay. Every new find has the potential to improve our understanding of our past.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thousands of interactions shaped this work. To each and every person, we would like to say: Thank you. Your help is remembered and appreciated.

With thanks to Charles Thomas Hodges (1950–2019) and James Fanto Deetz (1930–2000). Jim Deetz spoke of “small things forgotten” but he also wanted us to think globally. James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life (New York: Doubleday, 1977). Hodges led my research team at Flowerdew—the “staff,” locals supporting Jim’s program from UC Berkeley. Charley is a legend for detail. His Forts of the Chieftains: A Study of Vernacular, Classical, and Renaissance Influence on Defensible Town and Villa Plans in 17th-Century Virginia (Columbia: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, 2009) was 591 pages when he turned it in as his master’s thesis (College of William and Mary, 2003). Deetz often got exasperated with our intense focus. He once told us: “You will never see the forest or the trees, because you’re too busy looking at aphids.”

William Turnbaugh, “Post-Contact Smoking Pipe Development: The Narragansett Example, Proceedings of the 1989 Smoking Pipe Conference: Selected Papers, edited by Charles F. Hayes III, Research Records 22 (Rochester, N.Y.: Rochester Museum and Science Center, 1992), pp. 113–24.

David M. Givens, “Creating a Third Space: Material Culture, Colonialism, and Hybridity at James Fort,” master’s thesis, University of Leicester, 2015, p. 7.

John Cockburn, A Journey over Land: From the Gulf of Honduras to the Great South-sea (London: Printed for C. Rivington, 1735).

Francisca Gili, Javier Echeverria, Emily Stovel, Michel Deibel, and Hermann M. Niemeyer, “Las pipas del Salar de Atacama: Reevaluando Su Origin y Uso,” Estudios Atacameños, no. 54 (2017): 37–64.

Elizabeth Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed): An Examination of Late Woodland and Early Contact Period (A.D. 900–1665) Native Social Dynamics in the Middle Atlantic,” Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 2012, p. 182.

John Smith, The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580–1631), edited by Philip Barbour, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 1:149.

Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed),” pp. 90, 184, 210–12.

Sean M. Rafferty and Rob Mann, “Introduction: Smoking Pipes and Culture,” in Smoking and Culture: The Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North America, edited by Sean M. Rafferty and Rob Mann (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), p. xii.

John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina: Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of that Country . . . (London, 1709), p. 208.

Clay-stemmed pipes were also used by some cultures in Mexico and farther south.

Buck Woodard, Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, and Stephanie Hasselbacher, The High Plains Sappony of Person County, North Carolina and Halifax County, Virginia, Department of Historic Resources Research Report Series 21 (Richmond: Commonwealth of Virginia, 2017), pp. 15–18; available online at https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/HA-081_High_Plains_Sappony_NCVA_Christie_Indian_Settlement_2017_WM_report.pdf.

Matthew C. Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake,” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1988, p. 139.

Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed),” p. 65, fig. 3.2, Woodard et al., High Plains Sappony, p. 6, fig. 1.

Edward S. Rutsch, Smoking Technology of the Aborigines of the Iroquois Area of New York State (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1973); Barry G. Kent, Susquehanna’s Indians, Anthropological Series 6 (Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1975).

Woodard et al., High Plains Sappony.

L. Daniel Mouer, Mary Ellen N. Hodges, Stephen R. Potter, Susan L. Henry Renaud, Ivor Noël Hume, Dennis J. Pogue, Martha W. McCartney, and Thomas E. Davidson, “Colonoware Pottery, Chesapeake Pipes, and ‘Uncritical Assumptions,’” in I, Too, Am America: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life, edited by Theresa A. Singleton (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), pp. 83-115.

Carolus Clusius (Exoticorum libri decem [1605], p. 310), quoted in Dane T. Magoon, “ ‘Chesapeake’ Pipes and Uncritical Assumptions: A View from Northeastern North Carolina,” North Carolina Archaeology 48 (1999): 107–26.

Givens, Creating a Third Space, p. 36.

Don H. Duco, “The Clay Tobacco Pipe in Seventeenth-Century Netherlands,” in The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe, vol. 5, Europe, pt. ii, edited by Peter Davey, BAR International Series 106ii (Oxford: B.A.R., 1981), pp. 368–468.

Givens, Creating a Third Space, pp. 1, 16, 41–50.

Ibid., pp. 14, 16.

Nicholas Luccketti, William M. Kelso, and Beverly A. Straube, APVA Jamestown Rediscovery: Field Report 1994 (Jamestown, Va.: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, 1994), p. 28.

Merry Abbitt Outlaw, personal communication, September 2019.

Martha W. McCartney, Jordan’s Point, Virginia: Archaeology in Perspective, Prehistoric to Modern Times (Richmond: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 2011).

Silas D. Hurry and Henry M. Miller, “The Varieties and Origins of Virginia Red Clay Tobacco Pipes: A Perspective from the Potomac Shore,” paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Kingston, Jamaica, 1991.

Diane Dallal, “The Tudor Rose and the Fleurs-de-lis: Women and Iconography in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Clay Pipes Found in New York City,” in Smoking and Culture: The Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North America, edited by Sean M. Rafferty and Rob Mann (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), pp. 207–39; Duco, “Clay Tobacco Pipe in Seventeenth-Century Netherlands.”

Emerson W. Baker, The Clarke & Lake Company: The Historical Archaeology of a Seventeenth-Century Maine Settlement, Occasional Publications in Maine Archaeology 4 (Augusta: Maine Historic Preservation Commission, 1985), p. 25.

Richard Veit and Charles A. Bello, “‘A Unique and Valuable Historical and Indian Collection’: Charles Conrad Abbott Explores a 17th-Century Dutch Trading Post in the Delaware Valley,” Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology 15 (1999): 95–123.

Luckenbach and Kiser, “Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing”; Luke Pecoraro, “Mr. Gookin out of Ireland, wholly upon his owne adventure”: An Archaeological Study of Intercolonial and Transatlantic Connections in the Seventeenth Century,” Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 2015.

Susan L. Henry, “Terra-Cotta Pipes in 17th-Century Maryland and Virginia: A Preliminary Study,” Historical Archaeology 13, no. 1 (1979): 14–37; Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake,” p. 139.

Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten.

Luckenbach and Kiser, “Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing.”

Lauren Kathleen McMillan, “Community Formation and the Development of a British-Atlantic Identity in the Chesapeake: An Archaeological and Historical Study of the Tobacco Pipe Trade in the Potomac River Valley ca. 1630–1730,” Ph.D. diss., University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 2015, p. 250; Pecoraro, “Mr. Gookin out of Ireland.”

McMillan, “Community Formation,” p. 255. After examining the repetition of Bookbinder decoration, an inclusive classroom educator recently suggested that the maker might have been in the autism spectrum. Laura Powell Kiser, M.I.S. Special Education, Education, Media and Technology, personal communication, October 2019.

Luckenbach and Kiser, “Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing.”

Anna Agbe-Davies, “Up in Smoke: Pipe Making, Smoking, and Bacon’s Rebellion,” Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2004; Lauren Kathleen McMillan, “Seventeenth-Century Local Pipe Production and Distribution in the Upper Chesapeake,” paper presented at the Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference, March 2016, Ocean City, Maryland.

Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake,” p. 146.

Martha W. McCartney, “The Walter Aston Site (44CC178) and Westbury Plantation (44CC103, 44CC179, and 44CC180), Charles City County, Virginia” (Richmond: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1989), pp. 57–64.

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, 66 vols. (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1885–1901), s.v. “Aston, Walter,” by Samuel Rawson Gardiner, vol. 2 (1885), p. 213.

McCartney, “Walter Aston Site (44CC178) and Westbury Plantation (44CC103, 44CC179, and 44CC180),” p. 45.

R. P. Stephen Davis Jr., Patrick C. Livingood, H. Trawick Ward, and Vincas P. Steponaitis, Excavating Occaneechi Town: Archaeology of an Eighteenth-Century Indian Village in North Carolina, CD-ROM (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

McCartney, “Walter Aston Site (44CC178) and Westbury Plantation (44CC103, 44CC179, and 44CC180),” p. 45.

Maureen Meyers, “From Refugees to Slave Traders: The Transformation of the Westo Indians,” in Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South, edited by Robbie Ethridge and Sheri Shuck-Hall (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Kristalyn Shefveland, “Indian Enslavement in Virginia,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, April 7, 2016, available online at https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Indian_Enslavement_in_Virginia#start_entry.

Kathryn Sikes, “Stars as Social Space? Contextualizing 17th-Century Chesapeake Star-Motif Pipes,” Post-Medieval Archaeology 42, no. 1 (2008): 75–103.

Luckenbach and Kiser, “Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing.”

Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake.”

Barry Gaulton, 17th and 18th Century Marked Clay Tobacco Pipes from Ferryland, NL (Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador, 2006), available online at https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/pipemarks-introduction.php.

Beverly Straube, personal communication, October 2019.

Ann B. Markell, “44PG92—Flowerdew Hundred: Site Report,” unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia, 1990.

McMillan, “Community Formation,” p. 63.

Luckenbach and Kiser, “Seventeenth-Century Tobacco Pipe Manufacturing”; McMillan, “Community Formation,” p. 63.

McMillan, “Community Formation,” p. 63.

Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed),” fig. 7.2b.

Lauren K. McMillan and D. Brad Hatch, “Reanalysis of Nomini Plantation (44WM12): Preliminary Interpretations,” paper presented at the 73rd Annual Meeting of the Archeology Society of Virginia, Virginia Beach, Virginia, 2013; McMillan, “Community Formation,” pp. 63, 197–99.

L. Daniel Mouer, “Chesapeake Creoles: The Creation of Folk Culture in Colonial Virginia,” in Archaeology of 17th Century Virginia, edited by Theodore R. Reinhart and Dennis J. Pogue (Richmond: University of Virginia Press), pp. 54–74.

Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes of the Chesapeake.”

Mouer et al., “Colonoware Pottery, Chesapeake Pipes, and ‘Uncritical Assumptions’ ”; Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed),” p. 182.

Cockburn, A Journey over Land; C. S. Everett, “‘They shalbe slaves for their lives’: Indian Slavery in Colonial Virginia,” in Indian Slavery in Colonial America, edited by Alan Gallay (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), pp. 67–108; “New Street, Port Royal, Locally-Made Pipes,” Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (DAACS), available online at https://www.daacs.org/galleries/new-street-tavern-port-royal/.

Kenan Paul Heidtke, “Jamaican Red Clay Tobacco Pipes,” master’s thesis, Texas A&M University, 1992; “New Street, Port Royal, Locally-Made Pipes,” DAACS.

Al Luckenbach, “The Swan Cove Kiln: Chesapeake Tobacco Pipe Production, Circa 1650–1669,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 1–14.

Allan Peacey, “The Development of the Clay Tobacco Pipe Kiln in the British Isles,” in The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe, vol. 14, edited by Peter Davey, BAR International Series 246 (Oxford: B.A.R., 1996), pp. 40, 269; Luckenbach, “Swan Cove Kiln.”

Martha W. McCartney, Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607–1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), pp. 239–41, 771–75.

McMillan, “Community Formation,” pp. 302–5.

Paul R. Huey, “The Archaeology of 17th-Century New Netherland since 1985: An Update,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 34, no. 1, article 6 (2005), available online at http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/neha/vol34/iss1/6; McMillan, “Community Formation,” p. 124.

Bert van der Lingen, “Een Amerikaanse Chesapeake pijp en een Turkse tsjiboek uit een sloot in de Schermer,” Stichting PKN Jaarboek 2013, edited by Arjan de Haan and Bert van der Lingen (Leiden: Stichting PKN, 2013), pp. 59–63, 151–52.

Pecoraro, “Mr. Gookin out of Ireland.”

Magoon, “ ‘Chesapeake’ Pipes and Uncritical Assumptions,” pp. 113–15.

Mouer et al., “Colonoware Pottery, Chesapeake Pipes, and ‘Uncritical Assumptions,’” p. 104.

Bollwerk, “Seeing What Smoking Pipes Signal(ed),” p. 398; Emerson, “Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake.”

Silas Hurry, “Terra Cotta or Red Clay Tobacco Pipes from St. Mary’s City: A View from the Potomac Shore,” paper presented at Workshop No. 15, Small Finds Work Group, Accokeek, Maryland, 2018.

J. Cameron Monroe, “Negotiating African-American Ethnic Identity in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake: Colono Tobacco Pipes and the Ethnic Uses of Style,” master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1999, pp. 47–51.

Lingen, “Een Amerikaanse Chesapeake pijp en een Turkse tsjiboek uit een sloot in de Schermer,” pp. 59–63, 151–52.