Goat, Anthony Baecher, ca. 1880. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 7/8". (Courtesy, American Folk Art Museum, promised gift of Ralph Esmarian; photo, John Bigelow.) This figurine exhibits Baecher’s command of glazes by using manganese over slip. Marked three times: BAECHER/WINCHESTER VA.

Vase, Anthony Baecher, Winchester, Virginia, ca. 1865–1880. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9". (Courtesy, Dr. and Mrs. George E. Manger Collection.) This vessel demonstrates his striking glaze eVects resulting from the use of manganese, copper, and lead oxides over a slipped engobe. Stamped twice: BACKER.

David Hazzard (left) and Gene Comstock completing the 3.5 x 0.5 m trench at the site of the Baecher Shop, Frederick County, Virginia. (Photo, Christopher T. Espenshade.)

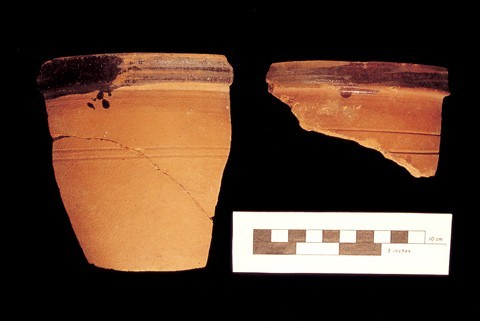

Storage jar fragments, Anthony Baecher Shop, Frederick County, Virginia, 1864–1889. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Photo, Alain C. Outlaw.) These fragments are characteristic of Baecher’s lesser-known utilitarian vessels. The rims are squared on the exterior, and the interior glazes are dark brown to black. Note the sandy texture of the unglazed exterior.

Anthony W. Baecher was an earthenware potter in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia in the nineteenth century. His work has been widely hailed as among the best folk pottery of the Shenandoah Valley based on a wide variety of surviving masterpieces.[1] The recent archaeological testing of the Anthony Baecher site in Frederick County, Virginia, highlights the two faces of Anthony Baecher.[2] Baecher was a highly skilled, highly creative ceramic artist, but he also made many rather pedestrian pots. This contrast underlines the inherent biases in personal and museum collections versus the pots found in the archaeological record.

Baecher is generally recognized for three strengths: his palette of glaze/ underglaze combinations; his use of applied decoration; and his skill in making animal and human forms as stand-alone items or accents on ornate pieces (figs. 1-2). Ceramic historian Gene Comstock observes: “Of all the pottery produced in the Valley, Bacher’s is the most likely to be characterized as a true representation of American folk art in spite of his resurgent rococo and strong German influences.”[3] Likewise, early historians Alvin Rice and John Stoudt were impressed with Baecher’s potting: “A. W. Bacher was, without a doubt, the most skilled of the master potters of the Shenandoah Valley, and his influence is apparent in the later products of both S. Bell and Son, and the Eberly Pottery.”[4] The 2002 preliminary testing of Baecher’s Virginia shop provided a very different view. Skelly and Loy, Inc., conducted limited testing at Baecher’s 1864–1889 shop near Winchester (fig. 3), and also examined material from earlier work at the site by others.[5] A total of 2,252 sherds was analyzed (fig. 4). The collection is dominated by simple storage jar forms with interior lead glazing, generally unadorned bases, heavy rims, and incised lines on their shoulders. There is a high degree of variability in the width and thickness of rims, and there is no evidence that templates were used in forming the rims. Less than 0.5 percent of the assemblage has glaze/underglaze combinations other than basic lead glaze. No slip-trailing, applied decoration, or sgraffito is evidenced. Handles are pulled, rather than extruded. Only two possible figurine fragments are encountered. In general, the day-to-day vessels made at the Baecher shop are less than spectacular and do not reflect the artistic skills of the potter. Indeed, it could be argued that, aesthetically, ’s utilitarian ware shows devolution from earlier regional traditions.[6]

Overall, the archaeology of the Baecher site reminds us of the biases in our databases. Museums and private collectors tend to hold the most unusual, most ornate, and least utilitarian pieces made by a potter. Archaeological samples may not capture the full range of production at a site, are biased toward failures, and tend to emphasize exactly those items for which the least care was taken. These contrasting databases can yield a somewhat complete picture only when taken together. In the current case, both faces of Anthony Baecher are legitimate. Baecher was an extremely skilled folk artist, but the competitive demands of the Valley market forced him to simplify his bulk production. Baecher balanced his occasional tours de force against his day-to-day economic baseline of mundane vessels.

Christopher T. Espenshade

Archaeologist

Skelly and Loy, Inc.

<cespenshade@monroeville.skellyloy.com>

H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994).

During his career, Baecher also spelled his name Packer, Bacher, and Backer.

Comstock, The Pottery of the Sehnandoah Valley, p. 164.

Alvin H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasburg, Va.: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929), p. 88.

Dr. Gene Comstock, Robert Jolley of the Winchester Regional Preservation Office of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (VDHR), and David Hazzard of the Threatened Sites Program (VDHR) assisted Skelly and Loy, Inc. in the excavation. Robert Jolley has been conducting research concerning the longevity of the earthenware tradition in Frederick County, Virginia, and has noted this apparent devolution in much of the late nineteenth-century earthenware.

Christopher T. Espenshade and Linda Kennedy, “Skilled Potters, Mundane Pots: Preliminary Archaeological Testing of the Anthony Baecher Pottery Shop (44FK550), Frederick County, Virginia, 2002.” Report for the Threatened Sites Program, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, Va.