Dish, Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection; unless otherwise noted, photos by Gavin Ashworth.)

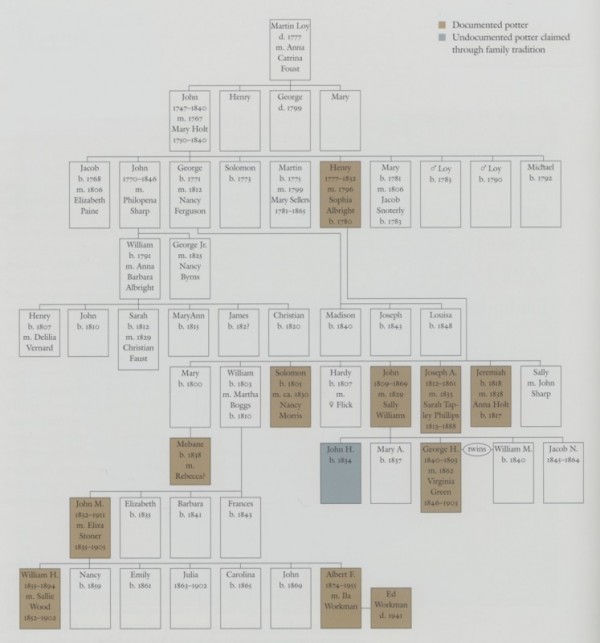

Loy Family of Potters. (Compiled by Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton; artwork, Wynne Patterson.)

Flask, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1770–1790. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

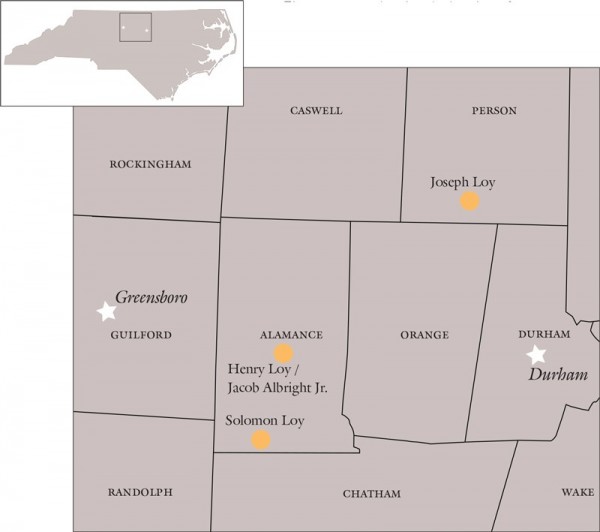

Map showing the location of Loy family potteries.

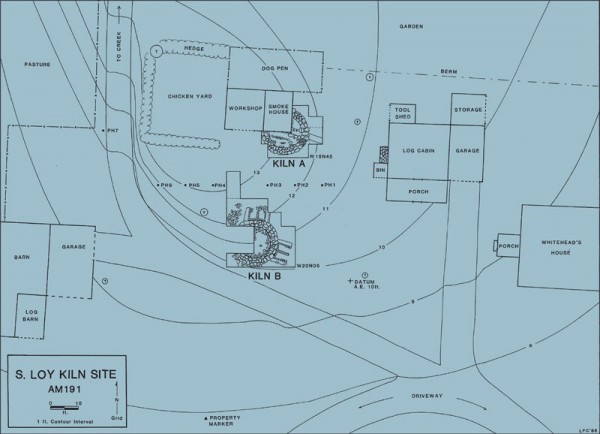

Drawing of site 31AM191 showing the location of two circular kilns, a log house, a barn, and other landscape features following archaeological investigations. (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) The smokehouse covers 25 percent of the foundation of the downdraft kiln (A). The updraft kiln (B) was not entirely excavated because of a fruit tree on top of the west firebox.

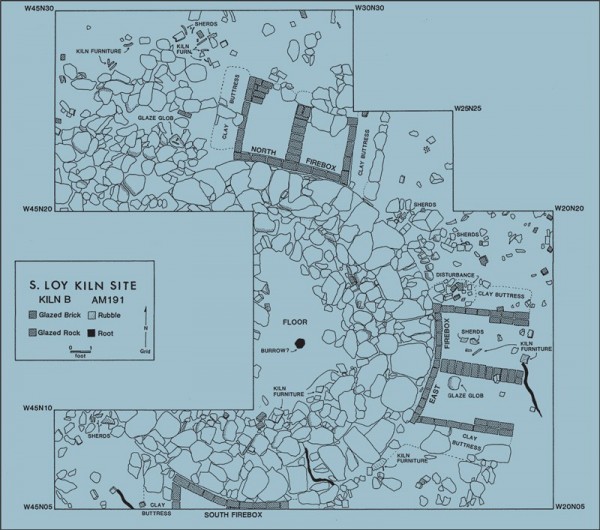

Drawing of the updraft kiln after excavation. (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.) Double-chambered, or “hob,” fireboxes are located equidistant along the perimeter of the foundation wall. The interruption in the foundation stone was for a doorway.

View of the updraft kiln during final stages of excavation. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.)

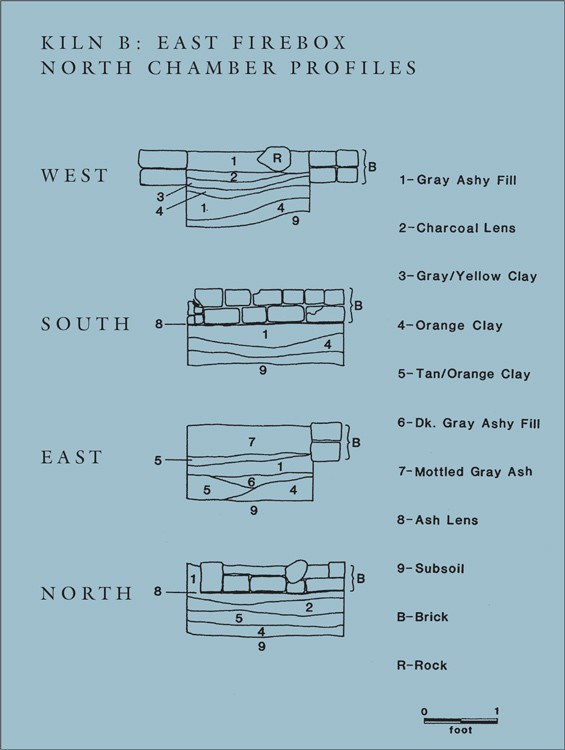

Profile drawings of the east firebox of the updraft kiln (B). (Artwork, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton.)

View of the east firebox following excavation. (Photo, Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton).

Pipe and kiln furniture recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware and high-fired clay. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The pipes and supports would have been placed in a sagger. Fragments of thirteen pipe heads were recovered during excavations, six of which were in the updraft kiln. Five fragments were unglazed earthenware, two were lead-glazed, and six were salt-glazed stoneware. The unglazed earthenware examples are fluted, and one has a face at the outer elbow joint. The fluted examples matched a pewter pipe mold found in the chinking of the log house on the site.

Jar, Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1830–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 7/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) This jar bears the maker’s full name. Solomon also used stamps and incising to mark his ware. A large cobalt-decorated stoneware crock and a unique salt-glazed stoneware grave marker dated 1834 have square floral stamps. Fragments of large crocks bearing the mark of Solomon’s son John M. Loy were recovered at Solomon’s site (31AM191). Some had debased cruciform motifs, like those on this example.

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12". (Private collection.) Loy’s dishes are generally lighter and thinner than those made by Moravian potters in Bethabara and Salem, North Carolina. He used green, orange, brown, and black slips to decorate earthenware, and brown and blue slips to decorate stoneware.

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 12. Some late Moravian dishes have concave backs, but they do not flare as dramatically as those associated with Loy.

Fragmentary bowl recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Bowl, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 6 3/16". (Private collection.)

Detail of the back of the bowl illustrated in fig. 15.

Bowl fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Tripartite stylized leaves like those on these fragments are common on slipware attributed to Loy.

Mug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 3/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Mug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Handle fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The molding on the fragment at the upper right is similar to that of the handle on the mug illustrated in fig. 19.

Fat lamp, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6 5/8". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Container, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.) The foot of this object is similar to those on the mugs illustrated in figs. 18 and 19.

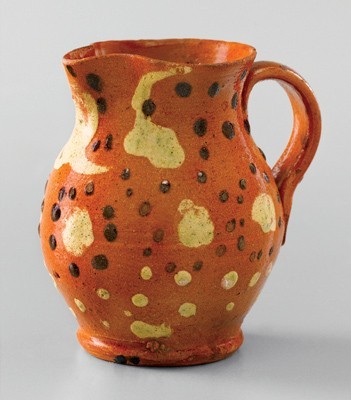

Cream jug, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 4". (Private collection.) The decoration on this cream jug is related to that on dish and hollow-ware fragments recovered at Loy’s site (see fig. 31).

Bowl, dish, and handle fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15". (Private collection.) This monumental dish is the largest example attributed to Loy.

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 1/2". (Private collection.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) The trailing on the fragment on the left is similar to that in the center of the dish illustrated in fig. 48, whereas the leaf motif on the right fragment relates to that in the cavetto of the example shown in fig. 44.

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Nested triangles occur on several paint-decorated chests from Berks County, Pennsylvania. As was the case with Martin Loy, many early Alamance County settlers had previously lived in Berks County.

Hollow-ware fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Bowl fragment recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 3/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Detail of the decoration on the marly of the dish illustrated in fig. 33.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the decoration on the marly of the dish illustrated in fig. 35.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/2". (Private collection.) This dish and the example illustrated in fig. 38 may be by Solomon Loy. If so, they probably date from the beginning of his career but no earlier than ca. 1825.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 5/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Bowl and saucer, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. Dimensions not recorded. (Private collection.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, attributed to Solomon Loy, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, The Barnes Foundation.) The back of this dish has post-firing marks similar to those on the examples illustrated in figs. 40 and 41.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 3/4". (Private collection.) This dish and the examples illustrated in figs. 44, 47, and 48 may be by Solomon Loy. If so, they date no earlier than 1825.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.) The plant motif in the center is a debased version of that found on dishes and hollow-ware forms decorated by earlier potters in the St. Asaph’s tradition.

Dish fragments recovered at Solomon Loy’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1825–1840. Bisque-fired earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 44.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1800–1835. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, Old Salem Museums & Gardens.)

Detail of the back of the dish illustrated in fig. 48.

Slipware fragments recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Handle fragments recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Joseph used copper oxide to produce a green glaze. His son George Haywood produced similar wares well into the 1860s.

Marble and candlestick fragment recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Bisque-fired and lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Handle fragment recovered at Joseph Loy’s pottery site, Person County, North Carolina, ca. 1833. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Slipware fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Pipe prop and anthropomorphic object recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. High-fired clay. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

Mug fragments recovered at Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery site, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1795–1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. (Courtesy, Research Labs of Archaeology, UNC-Chapel Hill.) Some of the mug bases from Albright’s site are similar to those associated with Solomon Loy.

Dish, Alamance County, North Carolina, 1790–1820. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 11". (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Jacob Albright Jr.’s pottery produced slipware with marbleizing like that in the lozenges on the marly of this dish.