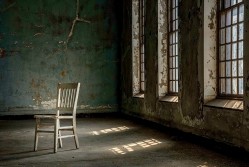

An empty chair used in contemporary “ruin porn.” Image by Precious Decay Photography.

An empty chair in a ward at Ellis Island. Image courtesy of Save Ellis Island.

The empty chair installation in The Chipstone Cosmos (2015), an exhibition on view in the Constance and Dudley Godfrey American Art Wing of the Milwaukee Art Museum. Image by Jim Wildeman.

Thomas Hicks (1823-1890), Kitchen Interior, 1865, Oil on panel, Dietrick American Foundation.

Thomas Hicks (1823-1890), Kitchen Interior, 1865, Oil on panel, Dietrick American Foundation.

H.S.W. and G.F. Root, The Vacant Chair, (1861-1865), The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries & University Museums.

An example of a maker considering the anthropomorphic qualities of chairs. Unknown, Chair, late 19th century, Carved and varnished cedrella with leather and brass tacks, Milwaukee Art Museum M2008.130.

Empty wheelchairs posed in Buffalo State Hospital, Buffalo, NY. Image by Ian Ference.

There is a visual trope that appears over and over again in so-called “ruin porn”[1] – the empty chair. In a decayed abandoned space usually bereft of other objects, photographers frame the chair in a dream-like space with melancholic narratives that spotlight human absence. The Chipstone Cosmos (2015), an exhibition on view in the Constance and Dudley Godfrey American Art Wing of the Milwaukee Art Museum, considers the historical precedence of this type of imagery. A sinuous chair is displayed next to Thomas Hicks’ 1865 painting Kitchen Interior, in which a remarkably similar chair references Civil War casualties. The label for this pairing includes American Civil War songs such as “The Vacant Chair” that used this imagery to evoke the loss of a loved one.[2] With the exception of that display, most installations of seating furniture in museums emphasize the objects’ sculptural qualities, provenance, materials, regionalism, and technology, without inviting visitors to imaginatively project past users. The unlikely intersection between contemporary abandonment photography and American Civil War cultural texts indicates the long-term usage of this symbol, but it also points toward the opportunity for museums to consciously leverage and direct the affective power of the empty chair.

In Thomas Hicks’ Kitchen Interior, he utilizes an empty chair in place of the Civil War soldier’s body. When Hicks completed this work, the Civil War had just come to an end. He chose to depict a woman peeling an apple in her kitchen, with light flooding in from a door held open by a broken chair. The back splat has a large section missing, and one of the arms was re-attached with rope or wire. While the chair evokes the absent husband or son, it also reflects his bodily wounds with a broken spine and a sutured or prosthetic arm. As historian Megan Kate Nelson argues, if men returned home from battle, many then faced life as “cripples.”[3] Along with destroyed buildings and forests, soldiers’ bodies became types of ruins that the American public used to contemplate the cost of war. At a time when photographers could capture the reality of battles including injuries and deceased bodies, Hicks used the chair—an anthropomorphic stand-in for the body with a back, seat, arms, legs, and feet—to indirectly depict injury, disability, and death.[4]

Ruin photographers pose and capture empty chairs to much the same effect as Thomas Hicks’ Kitchen Interior, and asylums are particularly potent historic sites for them to shoot. Alongside portraits of chairs, viewers will also likely see images of suitcases and clothing, or even clearer depictions of bodies in the form of unclaimed cremation urns. There is an undeniably melancholic overtone in these photographs, connecting the abandonment of the building to a perceived abandonment of the persons who once lived there. Photographers typically use the mood of these images to emphasize the struggles they believe to accompany mental or physical disability. In doing so, many create portraits of confined or sad lives within the walls of asylums without acknowledging the complexity of these institutions, which were originally built with noble intentions of helping patients before the results of overcrowding and understaffing gave the buildings their stigma.[5]

An emphasis on time connects abandonment photography and Thomas Hicks’ Kitchen Interior. Dust settles and walls crack in ruins, and peeled apples accumulate in Kitchen Interior. Time at once stands still and passes, asking viewers to consider what remains, what is lost, and why. By priming a museum visitor to consider loss through a label for an interior that materializes time, curators could use empty chairs to evoke missing persons. And by detailing complex stories relating to these individuals, museums have the opportunity to correct assumptions about past lives that result from contemporary biases. Pulling from a long history of photographers, painters, and songwriters who have all used this imagery to conjure past persons, curators could leverage this symbol to highlight the absences that a chair evokes, alongside the qualities of the object itself.

[1] The term “ruin porn” refers to photographs of contemporary ruins that are often criticized for aestheticizing poverty for the viewer’s pleasure. Refer to: Fred Vultee, “Finding the Porn in Ruin,” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 28:2 (June 2013): 142-145.

[2] Object label, The Chipstone Cosmos, Milwaukee Art Museum, 2015; H.S.W. and G.F. Root, The Vacant Chair (Richmond: Davis & Sons, 1861-1865).

[3] Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (Athens: The University of Georgia Press), 2012.

[4] Alexander Gardner, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (Washington: Philip & Solomons, 1866).

[5] Oliver Sacks, “Asylum,” in Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals, by Christopher Payne (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009) 1-5.

For more on this topic, see the Radio Chipstone episode The Empty Chair.