When Europeans first arrived in what they called the “New World,” they learned of tobacco from Indigenous peoples, who smoked the sacred plant to offer prayers in religious ceremonies and to seal treaties. English settlers, however, viewed tobacco as a potential cash crop. Seeing from the Powhatan that Virginia was an ideal climate for growing tobacco, the English settler John Rolfe began commercially growing tobacco using captured African laborers. As the value of unpaid servitude became increasingly evident, Virginia and other colonies began to codify slavery into law. Over the next two centuries, tobacco became the second largest cash crop in the southern United States, nearly all of it grown by men, women, and children who endured endless cruelty and inhumanity.

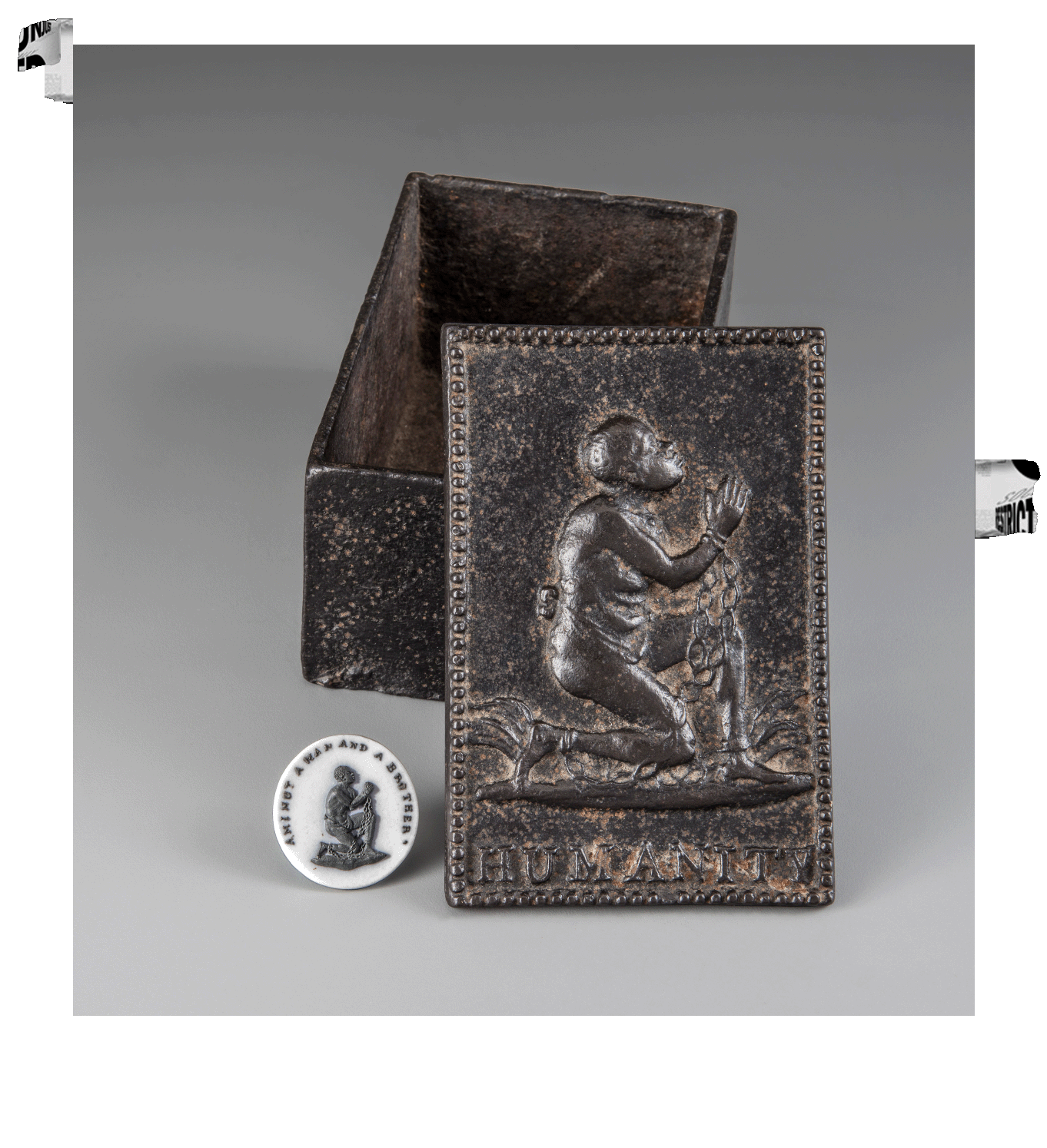

Created in England with the intention of sale on the abolitionist market, this cast iron box made to keep tobacco leaves fresh was one of the many products meant to end slavery in the Americas. On the lid is a depiction of a Black man shown either kneeling or praying with his hands clasped, a pose that was meant to help convince abolitionists that enslaved people deserved freedom.

The image was created around 1787 by the English ceramic manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood and the modeler William Hackwood, and the original design first appeared on small ceramic medallions along with the phrase “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?,” while here is only the word “HUMANITY.” Whether the makers or users of this tobacco box realized the irony of protesting slavery with an object that almost certainly contained tobacco grown and picked by enslaved labor is unknown. But the iron material of the box is a chilling and tactile reminder of the shackles and chains depicted in the scene of the kneeling enslaved man and worn around the legs, arms, and necks of enslaved Africans and their descendants throughout the Atlantic World.